Dominic Inouye’s column for the Milwaukee Independent has been exploring the nature of walking as a practice, as an integral part of street photography, and as a worldwide movement of neighborhood explorations called Jane’s Walk.

Almost 200 Milwaukee residents filled the “streets” of Turner Hall on May 2 for the kickoff of the 3rd Annual Jane’s Walk MKE, part of a worldwide movement that includes over 200 cities in over 40 countries. The evening celebrated a month-long series of free, citizen-led neighborhood explorations that will embody urban activist Jane Jacob’s legacy by observing, reflecting, questioning and collectively reimagining the places in which Milwaukeeans live, work, and play.

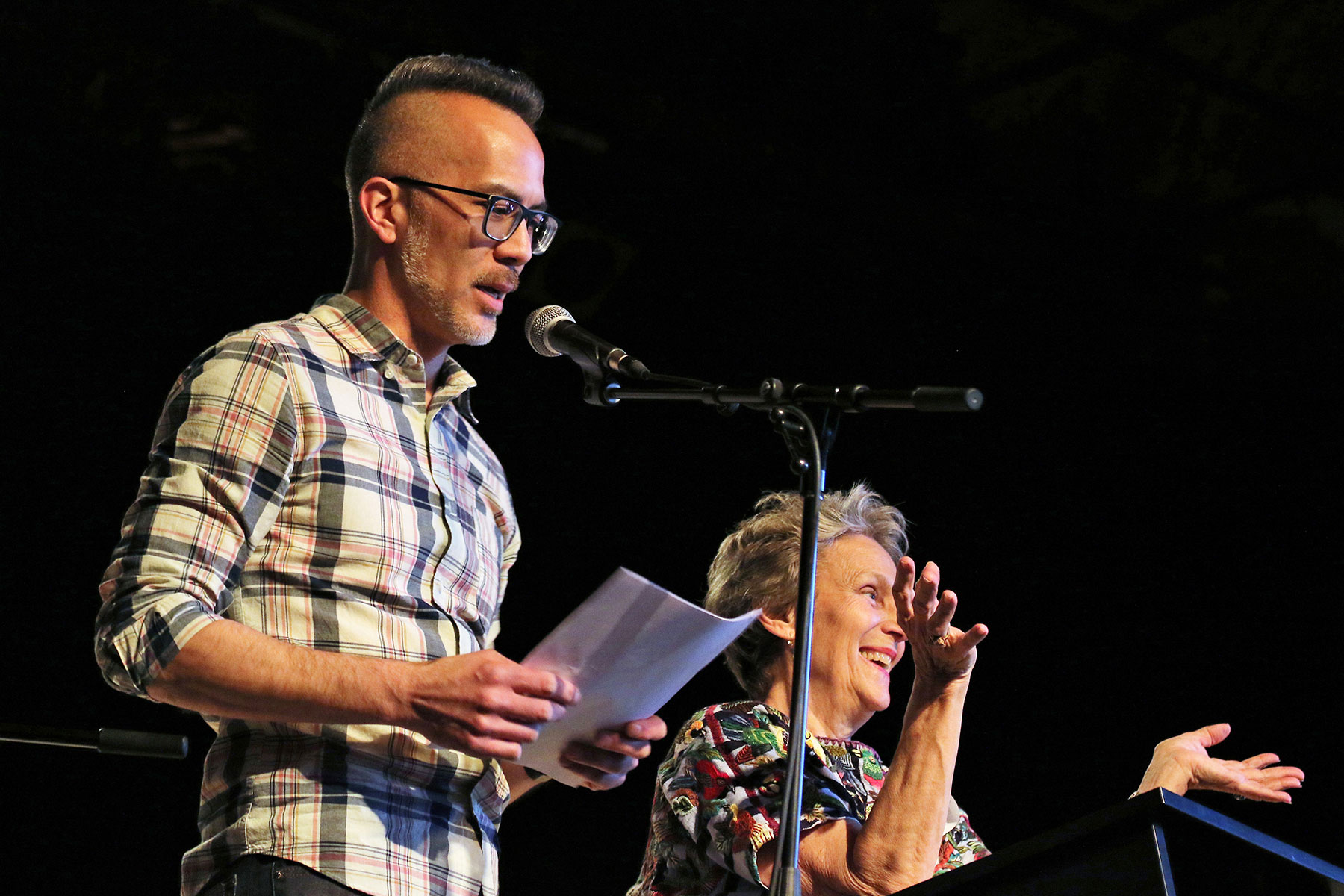

Representing ZIP MKE as an official Jane’s Walk MKE City Organizer, along with local activist and Vice President of the Milwaukee Turners Board of Directors Julilly Kohler, I was elated by how the evening developed.

Thirty community partners lined tape-simulated “streets” that cut through the Turner Hall floor space, sharing their work and messages. Attendees enjoyed mounded bowls of rice and Jamaican stew, inspirational folk music with protest lyrics, camaraderie, fellowship, and connections. What I thought would be a too-expansive space to fill instead hummed with movement and activity, a faux “sidewalk ballet,” as Jacobs would have called it.

To begin the program, Kohler and I lauded this year’s accomplishments compared to the first year, which only had three walks. Since February, eleven Organizing Committee (OC) members joined us once a week to coordinate over 30 walks – with the inclusion of bikes, runs, and paddles, from as far north as Westlawn Gardens, as far west as Hawthorne Glen, and as far south as Lincoln Avenue.

This month, a chorus of walks will fill the actual streets of the area: some historical and ecological, others neighborhood and placemaking assessments. Some will focus on our park system, others promote health and safety. There will be MacArthur Square kickball and Clarke Square mural art, a prayer walk and a book talk, French-inspired philosophical walks, and public performance art.

Over 500 individuals have already registered for these walks, which are still being submitted by residents. Kohler and I announced that we were now considered, in the parlance of the official Jane’s Walk international organization headquartered in Toronto, a “Chorus City” (compared to a “Dialogue City” last year and a “Murmur City” the first year), a designation based on the number of walks offered.

We also revealed Mayor Barrett’s official proclamation that May is now “Jane’s Walk MKE Month” and thanked the community partners that included 1,000 Friends of Wisconsin and the City of Milwaukee’s Path to Platinum initiative, the Fondy Market, and the Milwaukee Preservation Alliance, Menomonee Valley Partners and ReciproCITY, MacCanon Brown Homeless Sanctuary, and Vulture Space, among many others.

“As the years click off,” Kohler said, “I hope citizens learn about and dream about their neighborhoods and each others’ neighborhoods, and our whole city. I hope they become city partisans and protectors. And, yes, city builders.”

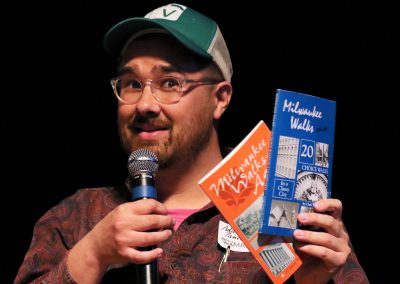

After a rousing Milwaukee-inspired rendition of “This Land is Your Land,” a panel of seven grassroots organizers took the stage to talk about their work in relation to mission of Jane Jacobs. Led by avid placemaker Michael Carriere, an associate professor of history at MSOE and co-coordinator of ReciproCITY, the panel included Adam Carr, Antoine Carter, Mikal Floyd-Pruitt, Tatiana Maida, Tim Syth, Ruth Weill, and Venice Williams. It was a who’s who of grassroots community advocates, artists, gardeners, and storytellers. Each in his or her own way has been a part of reimagining the narrative of the city.

And then the inevitable happened: a metaphorical spotlight shined on the Elephant of Homogeneity in the room. Panelist Venice Williams, Executive Director of Alice’s Garden, candidly noted that she, along with her fellow panelists, were “preaching to the choir.”

If any critics were in the house, they either did not speak up or were drowned out by Peter, Paul, and Mary and enthusiasts, bike safety advocates, BeeVangelists, and other city-builders. Throughout the discussion Williams emphasized the need to “show up” after events like the kickoff: to be present for each other, listen to each other, spend time in spaces where we are uncomfortable, look different or are not even invited. Williams challenged the audience:

The people who need to hear that they matter most will never walk into this space. So we have the responsibility to show up on street corners, where life literally enters. When was the last time you hung out on a street corner, and not one where most of the people look like you? If we’re going to start really having an impact in multiple areas the city, we have to show up more in places where we never should be or could be or maybe not invited to. And if you are not invited, invite yourself. Hear the voices that need to be heard.

As a valuable member of the choir who was applauded for also showing up on a daily basis, she then joked, “I don’t need to be heard. No one needs to hear me ever again. You don’t need to listen to me.”

As a City Organizer, both of these phrases gave me pause – “preaching to the choir” and “showing up.” Were the last three months of planning in vain? Therefore, it is a consideration for reflection.

The phrase “preaching to the choir” suggests, sometimes disparagingly, the pointlessness of a preacher trying to convert people who already believe the same things instead, of reaching out to those who need to hear or have not heard the message.

It is likely that most of us who preach a liberal social sermon have thought or felt, at one time or another, that we were just speaking in a vacuum or talking to a mirror. I have found myself at once overjoyed and somewhat deflated when I recognize the same faces and voices at so many events, especially at ones that I have coordinated.

In “Smallwaukee,” that is going to happen anyway, and it is not to say that I don’t love and respect these people. It is invigorating and empowering to look out into a crowd and recognize fellow compatriots, to know what binds this cadre together. These are the individuals that show up for tough discussions and new projects, marches, and campaigns regarding things like racial justice, fair housing, ecological sustainability, and immigrant rights. We share common values.

But if our work only attracts those with like minds – if the only people who attend Jane’s Walks this month are ones who already love exploring their city, who are already invested in efforts to improve it, then who are we not reaching? Why are we not reaching them? And what will be the effects, the outcomes? Are we just spinning our wheels? Now what? Many, many questions.

Even with the successes of the evening and the positive electricity in every corner of Turner Hall, were we really just preaching to the choir? And is preaching to the choir necessarily a “bad” thing?

Bill Sell (OC), a member of the Coalition for More Responsible Transportation in Wisconsin, insisted that “these activities, walks, kickoffs, and planning are all a piece of community building – and not a meaningless ritual.”

He reconnected with many individuals during the kickoff evening with whom he used to do activist work, and “they connected with Jane’s Walk and we built a forum that will affect the larger community.” Michelle Kramer (OC), the Director of Marketing & Business Development for Menomonee Valley Partners added, “Preaching to the choir doesn’t mean that new ideas aren’t surfacing. People gain new perspectives and continue on their personal journey of growth.”

Perhaps preaching to the choir does possess some value. Perhaps it is a necessary “ritual” that is not only about just “talking to” but about creating something new. Consider how a minister’s sermon is not meant to convert the faithful. They have already made a conscious decision to show up. Instead, the minister divines ways to contextualize and interpret the scriptures, to bring them to life and relevance for the present day.

In this sense, “preaching to the choir” is about opening up new ways of understanding the familiar. And not only new ways of understanding but, I would hope, new ways of acting. How many times can one hear the stories of David and Goliath or the Sermon on the Mount without them losing their gravitas, like walking past the same painting in the office day after day and eventually failing to even notice it? A minister’s challenge seems to be to keep these centuries-old stories fresh, and to give the congregation ways of applying them to daily life.

Good preaching, one could argue, is less comfortable muzak (“the weak can overcome the strong,” “the blessed shall inherit the earth”) than a call to action. It is a starting point rather than an ending. The congregation shares similar values, but how they understand that and then enact that personally and collectively is another thing.

While we speak so much about “activating” spaces, Lindsay Frost (OC), Water Projects Manager for the Harbor District, claimed that “preaching to the choir” was sometimes necessary in order to activate it:

The choir sometimes “knows” something, but the choir is not always compelled to act in accordance with what they know. It can take multiple iterations of preaching to influence an individual or a group to act, so hopefully each touch moves any given person from a passive, informed citizen, to an engaged, activated citizen.

I grew up a Catholic altar boy, familiar with the standardized lectionary – a series of scriptural readings that corresponds with the seven seasons of the liturgical calendar for worship. Over the course of three years, Sunday readings cycle through parts of the Bible with a similar schedule. After two or three years, the readings repeat.

Though the rhythmic repetition of the readings, familiarity spreads and over a lifetime offers many opportunities to understand anew, to be reinvigorated to action. In a Harper’s Magazine article entitled “Preaching to the Choir” (November 2017), Rebecca Solnit explained it this way: “Adults, like children, love hearing the great stories more than once, and most religions have prayers and narratives, hymns and songs, that are seen as wells of meaning that never run dry. People can lay down their sword and shield by the riverside one more time; there are always more ways to say how once we were blind but now can see.”

The point is there are always more ways to understand our blindness, our weaknesses, and challenges, and more ways to recover our sight, gain new perspectives, seek new solutions. Frost stresses the importance of expanding how she (and we) deliver the sermon, namely by connecting with more people and listening to more voices:

I have a robust circle of colleagues, friends, professional peers, supporters, and such in “my field,” but lately I have been feeling the need to spread my wings and learn about other facets of life in Milwaukee… One of the first things I remember hearing about the Jane’s Walk effort was that we cannot really care about our city or neighborhood, and we will not feel motivated to make it better, if we do not know what we are trying to save, change, or create. Walking around and hearing from others helps us build that motivation.

That is not to say the new-and-improved 2018 Jane’s Walk MKE does not have more room for growth. The panelists represented a diverse cross-section of the city, but they were hand-picked from the choir and they sang beautifully. They had already shown up, on the grassroots level, and effected change in their neighborhoods and in their city. The diversity of community organizations that represented their own good work was noteworthy. They filled the “streets” of Turner Hall because they already possessed strong voices.

Who, then, wasn’t represented on the panel and how to get them to the microphone? What organizations weren’t represented on the “streets” and how to make them visible to a greater audience? Who wasn’t in attendance at Turner Hall, downtown, at 5:30 p.m. on a Wednesday evening – and why?

We must think, too, of what panelist Tatiana Maida said that night about the south side of the city, suggesting that, as an immigrant community, there is not always the same sense of neighborhood belonging as in other parts of the city. Maida is the Healthy Choices Department Manager of an obesity intervention program at Sixteenth Street Community Health Center and focuses on family education and community leadership development.

She wondered how residents would connect with a song like “Milwaukee’s Land is Your Land, – full of “While all around me, were neighbors singing” and “Milwaukee was made for you and me!” – without that sense of belonging. She told the story of Teresa, a Mexican resident who lives south of Lincoln Avenue, who runs to her car every weekday at 8:00 a.m., with both of her children under her arms because there are shootings on that block:

I wonder how someone like Teresa can be helped… with nice words like “empowerment.” Here we are, those with similar values. But how do we move to action so someone like Teresa does not live with fear every morning. That fear does not let us look at the nice things that we might have in our neighborhood. The south side has so much life, so much vibrancy – but people are scared.

Moving beyond “preaching to the choir” is going to be difficult, but manageable. As an organization and a city, we are called to wrestle with questions like these: How can Jane’s Walk MKE better represent Milwaukee’s 28 ZIP Codes and 191 neighborhoods?

To be blunt I must ask: Where were the people of color, the young people, the immigrant community at the kickoff event? The elected officials, the representatives of neighborhood associations and business improvement districts? They were all invited, so why did they not attend?

More importantly, where were the disenfranchised, the disinvested, the unempowered? How could we have welcomed them? How do we grow the choir into an inclusive and unified celebration, critique and collaboration? Even if the choir were 600,000 strong, will neighborhood walks ever be able to eliminate Teresa’s fear of gun violence, a fear that prevents her and her family from enjoying the neighborhood? The elusive answer to this boggles my mind.

I can echo a St. Paul by saying that if our preaching does not explore the answers to questions like these, ones of faith in ourselves and others, ones of hope and faith in a safe, healthy, equitable, walkable Milwaukee, then our preaching is bootless.

If we only preach where we know we will not be challenged or interrogated, but do not challenge or interrogate our own preaching, we are only resounding gongs or clanging cymbals. If we have the ability and drive to explore the city, and if we have an optimism and idealism that can move mountains, but do not share these with our fellow citizens in all areas of the city by seeing them, listening to them, engaging and empowering them, then we are just preaching to the choir – and not “showing up.”

So how do we “show up”?

Addressing what Adam Carr called our tendency to avoid “epically difficult conversations” and instead embrace “numbness,” panelist Tim Syth of the co-working space 5Wise Workshop, admitted that he had to share the advantages of his own privilege:

If we do not address this numbness, we are never going to move forward. It is the duty of those who come from privilege to move that process along and to help those who do not come from privilege, who do not have a voice, and get those stories out there.

Local journalist Virginia Small (OC) spoke of creating and filling spaces:

I feel like the choir in Milwaukee could stand to grow bigger and louder. So maybe it can help to create a space for some honest dialogue, and then enlarging that space and recruiting more singers. There were comments by panelists that made me think in new ways, to think more about people who are not included in spaces like the one created at the kickoff. And how do we begin to work to foster more literal ‘safe spaces’ in our city, to say nothing of metaphorical ones.

Alverno College Associate Professor Joyce Tang Boyland (OC) spoke of boundary-crossing and cross-pollination:

I see events like this as a gathering place, and incubation lab for where the boundary-crossing relationships needed to generate ideas and energy for city-building. The image I have in my head is a field of wildflowers and bees, and we get to be bees that cross-pollinate and strengthen the population while having fun in the process.

And, according to Kramer,

Jane’s Walk MKE has the potential to be owned by everyone… Jane’s Walk MKE is an opportunity to invite others to learn about your space, or to be invited to someone else’s space to learn about their’s. It is partly about bridging invisible divides in our community. The first step in community building could be building familiarity, feeling more comfortable with our neighbors, in our own neighborhood, or in others. Most of us live in small bubbles and this is a way to step outside of it.”

Jane Jacobs herself – certainly no preacher in a bubble – said that “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” When Jacobs learned of the proposal by Robert Moses to build a freeway extension through Washington Square Park, she showed up, she wrote letters, she joined the park’s committee and became its media and community liaison, drummed up support from neighbors and politicians, co-chaired a Committee to Save the West Village, and wrote a Fortune magazine article that would lead to her opus, The Death and Life of American Cities.

She would go on to organize rallies against the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway that would have run through SoHo and Little Italy, demolishing hundreds of residential and commercial buildings and displacing over 2,000 residents. It was one such rally that got her jailed for a night for “inciting a riot.”

Jacobs preached to the choir, who joined her on the streets, at rallies, at public meetings, She also showed up in her own neighborhood and in others. Jane’s Walk MKE will continue to do the same and learn how to become better at both.

© Photo

Pat A. Robinson