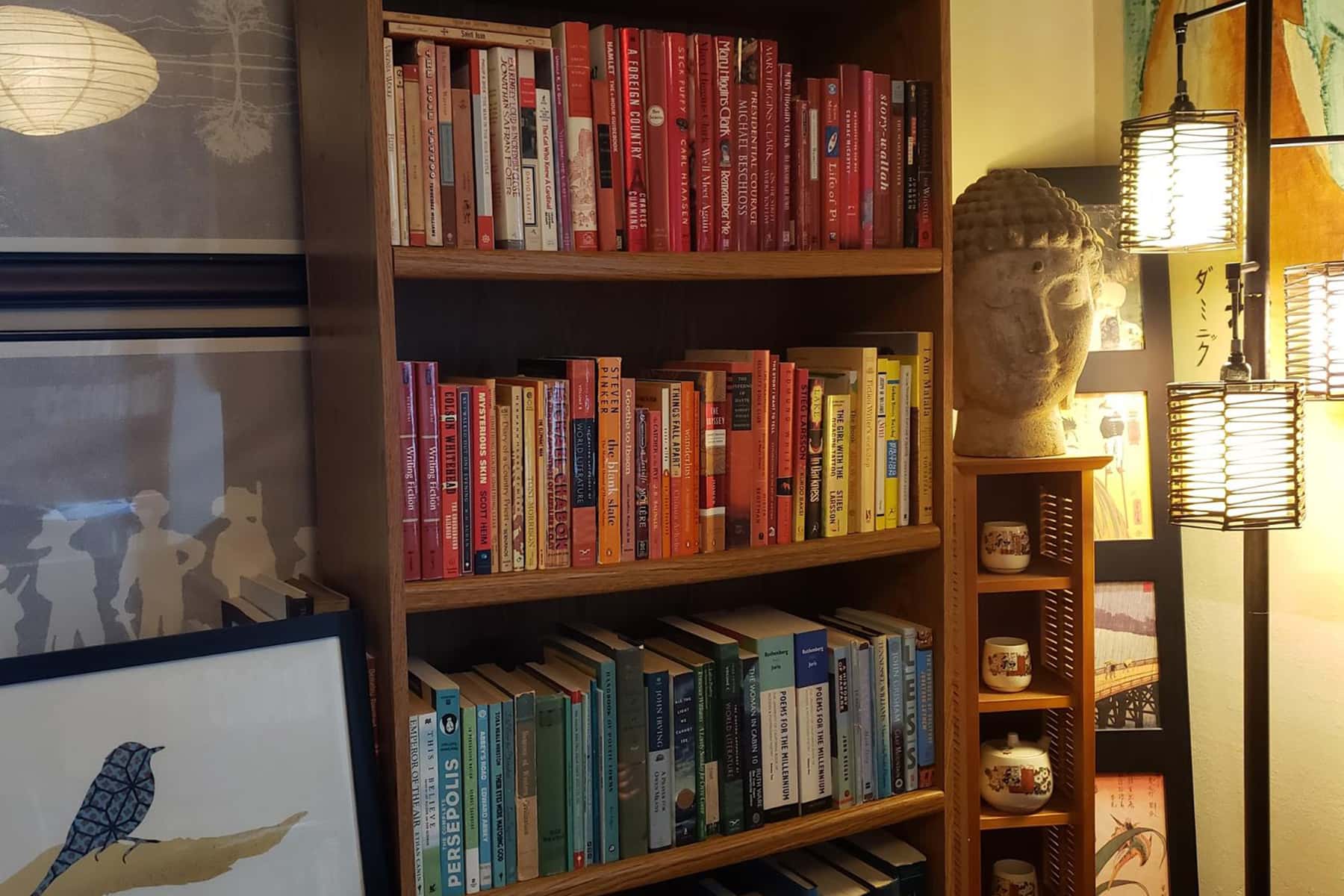

In the early days of the stay-at-home orders, I woke up and immediately – as if guided by some kind of whimsical chromatic spirit – commenced a ROYGBIV reordering of our library. Two hours later, I dusted off my hands and marveled at the rainbow of eighteen shelves thick with books read, reread, never finished and never cracked open. My meaningless but productive – and fun – quarantine task was accomplished. I don’t remember, however, sitting down afterward to read any of them.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago, when a former student, Nic, called me to catch up. He is getting ready to graduate with a degree in education and aspires to become a social studies teacher, so I offered my typical sage wisdom: teach who you are, teach with compassion, question everything you just learned in your education classes. Our chat inevitably led to books he remembered reading in my classes and at one point, he was surprised to learn that it is a rare day when I snuggle up with a book. “I would have thought that Mr. Inouye read a book a day!”

I informed Nic that most of the reading I’d done over the past two decades was of literature that I was bringing to my classes. I never had (or made) time for leisurely reading. If anything, I was committed to reading and teaching books that would allow my students and I to interrogate our vision for the world and to create ways of thinking and action that could change it: The Things They Carried[a], Persepolis, Like Water for Chocolate, The Lone Ranger & Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, The Woman Warrior, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, The Bluest Eye.

But my former student’s reaction got me thinking: Did I read anything this year? I must have. And if I did, what might my choices say about my experience of 2020? So I gathered a stack from the shelves. I had read more than I thought.

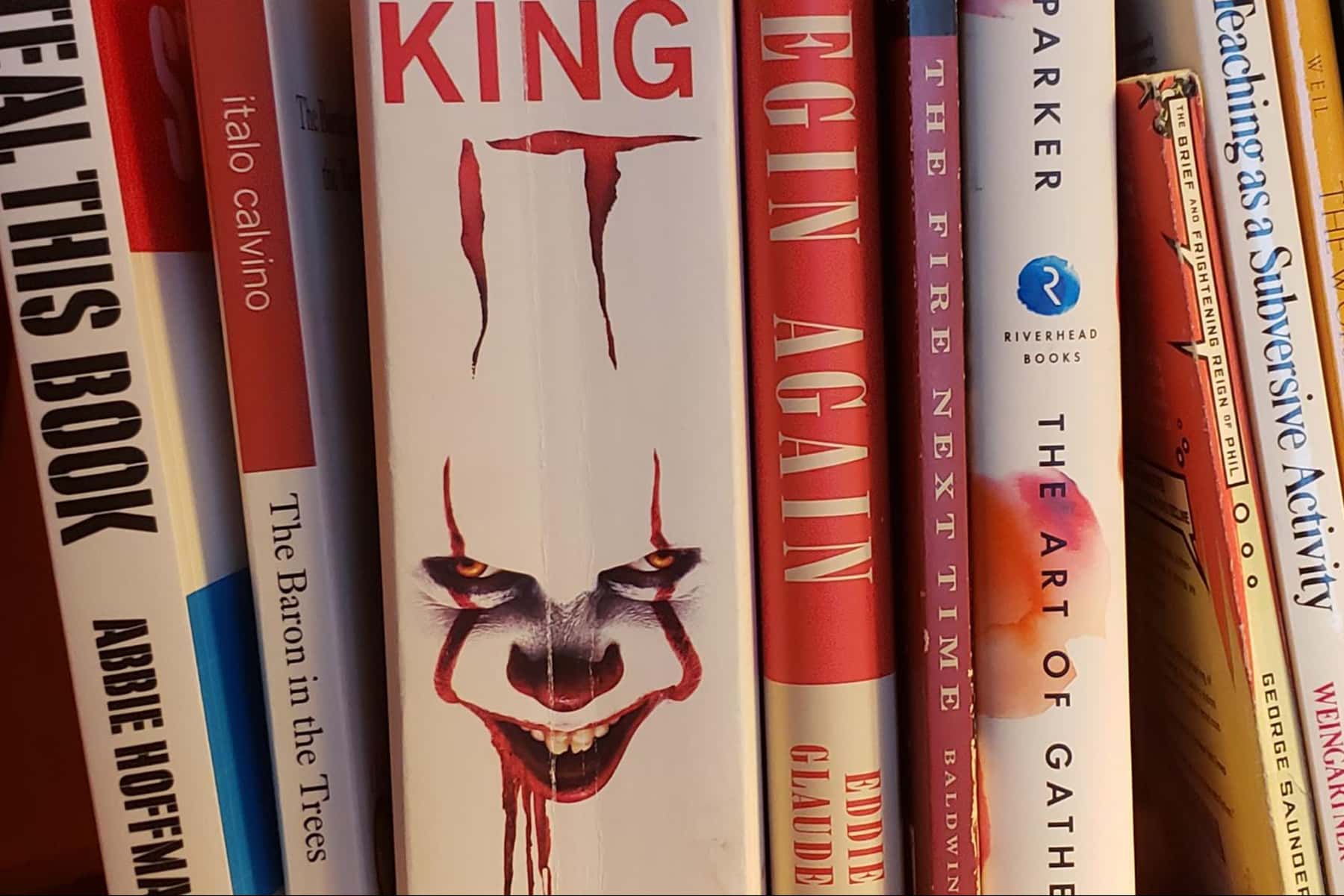

The first book I read in 2020 was Priya Parker’s The Art of Gathering. I was full of expectation for a new year with Jane’s Walk MKE: our team would begin meeting soon and a team member had suggested I read Parker months earlier. I remember being smitten with Parker’s insistence that a “bold, sharp purpose” could rescue every meeting or gala event, wedding or holiday celebration, from mundanity and staleness. No more doing things because “that’s the way we’ve always done it.” I planned for Parker’s handbook for creating unique and memorable gatherings to inform our May 2020 celebration: our launch event at Turner Hall and every walk, bike, paddle and roll through the city. As I wrote in March, our motto for the year, full of purpose and promise, was to be “Revisioning Milwaukee in 20/20.”

Alas, cue the quarantine. Everyone learned how to “pivot.” With Parker’s advice in the back of our heads, we quickly began collecting a series of twenty “Choose Your Own Adventures” and a handful of virtual tours for residents to enjoy on their own. Like most people, we knew that we would have to change the ways we gathered – or didn’t. With a year of pivoting under our belt, with months of experience with masks and physical distancing, and with vaccines on the horizon for many of us, I’m interested to see how we approach Jane’s Walk MKE this year. “Revisioning Milwaukee in 20/21” doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Of course, I reread bits of George Saunders’ The Brief & Frightening Reign of Phil every few months, as I have since Trump’s not-brief-enough reign began in 2016. A tale of borders and xenophobia in the land of Horner, Phil explores what happens when power goes unchecked. Whether it was his selfishly botched response to the pandemic or his racist assaults on the Black Lives Matter movement or his delusional presidential race and loss (yes, you lost, sir), I read and reread, aghast, at the parallels between Trump’s rhetoric and Phil’s “stentorian” and dictatorial speeches, which only occurred when his “brain pan” would slide off his head (it’s hard to describe, but you get the idea).

In Saunders’ novelette, it takes a deus ex machina in the form of the “Creator” to destroy Horner and start anew with a new race of creatures. Unfortunately, the story’s ending foreshadows a repeat of history: the better angels of our nature are overshadowed by a Hobbesian impulse to wage war against each other. This year, it wasn’t a divine hand but the American voters who surfaced long enough to say enough is enough. Only time will tell whether Saunders’ worldview – and Biden’s administration – will bring anything new and lasting and healing to our country.

As the year’s daily death toll progressed – both from the pandemic and from police brutality – I tried to escape into books new and old. Stephen King’s It seems an odd way to escape, but its epic story of an evil that lies just below the surface of American normality (aka white privilege) and surfaces every few decades in the Maine town of Derry – something about it seems so apt in 2020. I remember devouring the book as a teenager, reveling in the strength of the seven children who temporarily defeat the evil, who appears to them in the guise of Pennywise the Dancing Clown (I’ll resist any references to Trump’s hair). They rely on their personal and collective memories of childhood traumas and their trust in each other to form an alliance once more as adults when Pennywise resurfaces.

Pennywise is undaunted in its attempt to destroy the strength of youth and vitality by which it is so threatened. In a year when young people all around the country have joined forces to resist systemic racism and police brutality – in Milwaukee, marching for over 200 days now with demands for justice and reform – King’s horror story with a triumphant ending seems a strange but fitting reverie for our times.

I did start Nick Hornsby’s About a Boy as another way to escape (Hornsby’s narration is fresh and funny), and it, so far, suggests a transformation from self-interest, hedonism and white privilege to connection, purpose and humility. I’ve seen the film with fluttering-eyed Hugh Grant, so I know how it ends, but it’s a good read after all. My second reading of Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees interests me on more of a philosophical level. I’ve only recently started flipping the pages again, but so far it’s fabulist premise is making me wonder how much I and others try to escape the realities of the world – and what the consequences are.

In this Italian novel that begins in 1767, young Cossimo, a baron, escapes to the trees in an act of rebellion against his family (really, he just doesn’t want to eat the snails his sister has made for dinner). He vows to never come down – and doesn’t until he’s in his 60s, having learned how to exist and subsist above it all. The funny thing is that as he grows older, he welcomes visitors and lovers, politics and philosophy, into his treetop habitats. He just chooses who and what to get involved with.

His fantastical arboreal life reminds me of Max’s adventures “where the wild things are” in one of my favorite childhood books. Instead of being sent to his room for causing a ruckus and discovering a world where he can make and break the rules, however, Cossimo chooses to escape to a tree life where he can be a “baron in the trees.” And unlike Max, who gets homesick and returns to reality and a warm meal, Cossimo chooses to forever distance himself from the world below, where Europe is emerging from its revolutionary explosions into a new and uncertain future.

His experience of history, separated by tree trunks, branches and leaves, makes me wonder: Is seeing the world from a distance and refusing to participate in the nitty gritty of life, especially the difficult parts, really what we’re meant to do? Or is it standing firm on the ground and digging our heels in, even when the going gets rough? What do we miss by becoming an impertinent “wild thing” or stubborn noble? Like I wrote in May, the pandemic revealed that our concept of “heroism” is being redefined every day – and it’s not about leaving the world but immersing oneself in it.

And isn’t Cossimo’s escape a good example of a privilege that wouldn’t be afforded someone of his status? Not everyone can just pick up and move on as they please.

While I’m still working on Calvino’s novel chapter by chapter, then, I am also seeing that some of my reading this year has helped ground me in what’s really important right now, especially in regards to social justice.

After George Floyd’s murder in May, I reread James Baldwin’s letter to his nephew in The Fire Next Time, called “My Dungeon Shook.” Like my perusing of Phil every time Trump opened his mouth, in times like this I often seek out Baldwin as a sobering reminder and a moral compass. I need him to remind me of my privilege and of what’s at stake even, sadly, today:

You were born where you were born,” he tells his nephew, “and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth, you have been told where you could go and what you could do (and how you could do it) and where you could live and whom you could marry.

So unlike Max and Cossimo, who got to choose where they would reside and how, Baldwin’s nephew has no choice and is instead born into an America of systemic limitations. Baldwin describes how “the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar.” He warns that as the Black man “moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.” The system will break. But it will take action, not escapism.

Unfortunately, Baldwin knew that even white Americans who think they’re non-racist fear taking action because “to act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger.” Instead, they too often take the easy route and escape to the safety of their privilege. Baldwin believed, naively, that love would force white Americans “to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.” Little did he know in 1962 that in 2020, America would still be wrestling with the question of whether Black lives matter.

Even as I protested this summer, I felt I, too, was taking the easy route: protesting during the day instead of joining the marchers at night when the likelihood of confronting rubber bullets, tear gas, and arrest was greater. I took comfort in the safety of protests like the Black is Beautiful bike rides or March with PRIDE for #BLM, which I photographed in June. After rereading some Baldwin, then, I picked up a copy of Eddie S. Glaude’s 2020 book Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America & Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own. I’m looking forward to finishing it this next year and seeing if its urgent lessons force me to be even more committed, in different ways, where more is it at stake for me.

I realize, however, that confronting the police on the streets isn’t for everyone, that it takes all of us, in different lanes converging on one vast highway of change, to make a difference. My first year of working with Teens Grow Greens, during a pandemic and during the protests, helped me realize that the very work I was doing, that our Black and Brown students do, was indeed one of those lanes, as I wrote in June.

It’s not surprising, then, that some of the other books I pulled off my shelf were ones I read to help me and our Teens Grow Greens team prepare teens to be vulnerable and strong in an uncertain new year. Another of my go-to books, this time for all things educational, is Neil Postman & Charles Weingartner’s Teaching as a Subversive Activity. I wrote in July about what they called, in 1969, “the new education” which would create “a new kind of person, one who – as a result of internalizing a different series of concepts – is an actively inquiring, flexible, creative, innovative, tolerant, liberal personality who can face uncertainty and ambiguity without disorientation, who can formulate viable new meanings to meet changes in the environment which threaten individual and mutual survival.”

Young people, long used to the effects of racism and now used to face masks and isolation during a global pandemic, need new tools to not only navigate but to chart new courses in the coming years. So I looked to Zoe Weil’s The World Becomes What We Teach to learn what it will take to educate a generation of “solutionaries.” To Kyle Schwartz’s I Wish For Change, about “unleashing the power of kids to make a difference.” I learned from Torie Weiston-Serdan’s Critical Mentoring, which lays out a guide meant for educators to “take collective action and to do it alongside our young people.” I will try to adopt the phrase she repeats – “Nothing about us without us” – into the Teens Grow Greens program this next year, as we move to elevate teen voices even more and invite them to co-create the program with us. And I learned about “abolitionist teaching” from Bettina L. Love. Her book We Want to Do More Than Survive quotes educator Maxine Greene, who said, “To commit to imagining is to commit to looking beyond the given, beyond what appears to be unchangeable. It is a way of warding off the apathy and the feelings of futility that are the greatest obstacles to any sort of learning and, sure, to education for freedom … We need imagination.”

Indeed, we need imagination.

We need it as we continue changing and improving the ways we gather. We need it as we confront oppressive rulers and defeat evil in the form of murderous clowns or murderous police. And we need it to help us decide when to have our heads in the clouds (or trees) and when to commit to confronting the real problems right in front of us.

So yes, Nic, I do read. I hadn’t reflected on how much and why. My 2020 book list has certainly helped me imagine and reimagine myself and our shared future.

I just wonder what my last book purchase of 2020 says about my 2021: Abbie Hoffman’s controversial countercultural Steal This Book. Stay tuned.

© Photo

Dominic Inouye