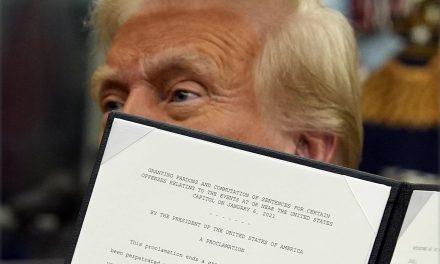

As the visuals of TV news broadcasts assault our minds with horrific images, turning away from them is both a reflex and a defense. As heart breaking as is to see photos of our country throwing tear gas at women and children or carnage from the latest mass shooting, it is a distant situation for most Americans. Which is to say, privilege provides a safe harbor from the terrible actions that social complicity allows and shared blindness foments.

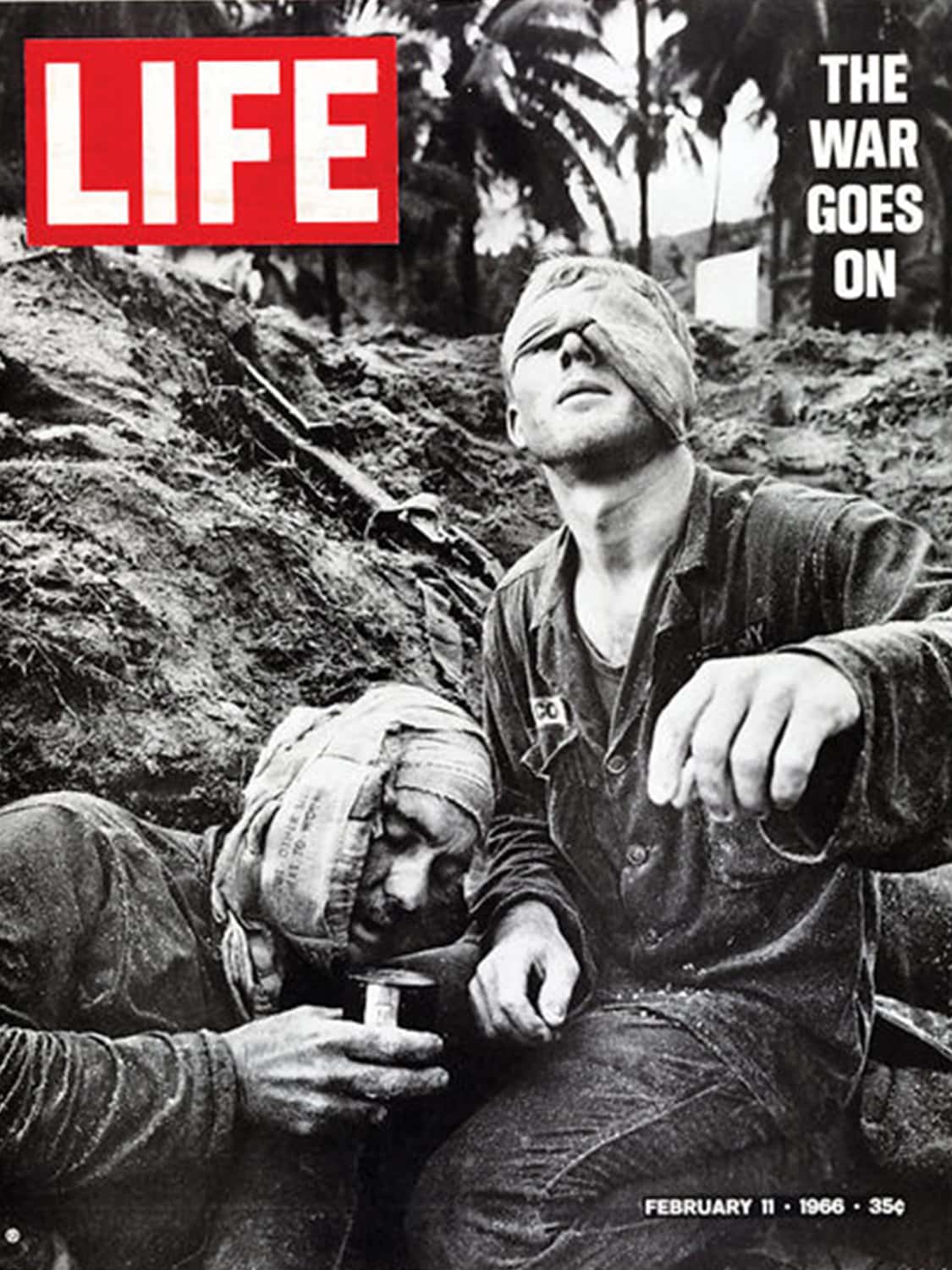

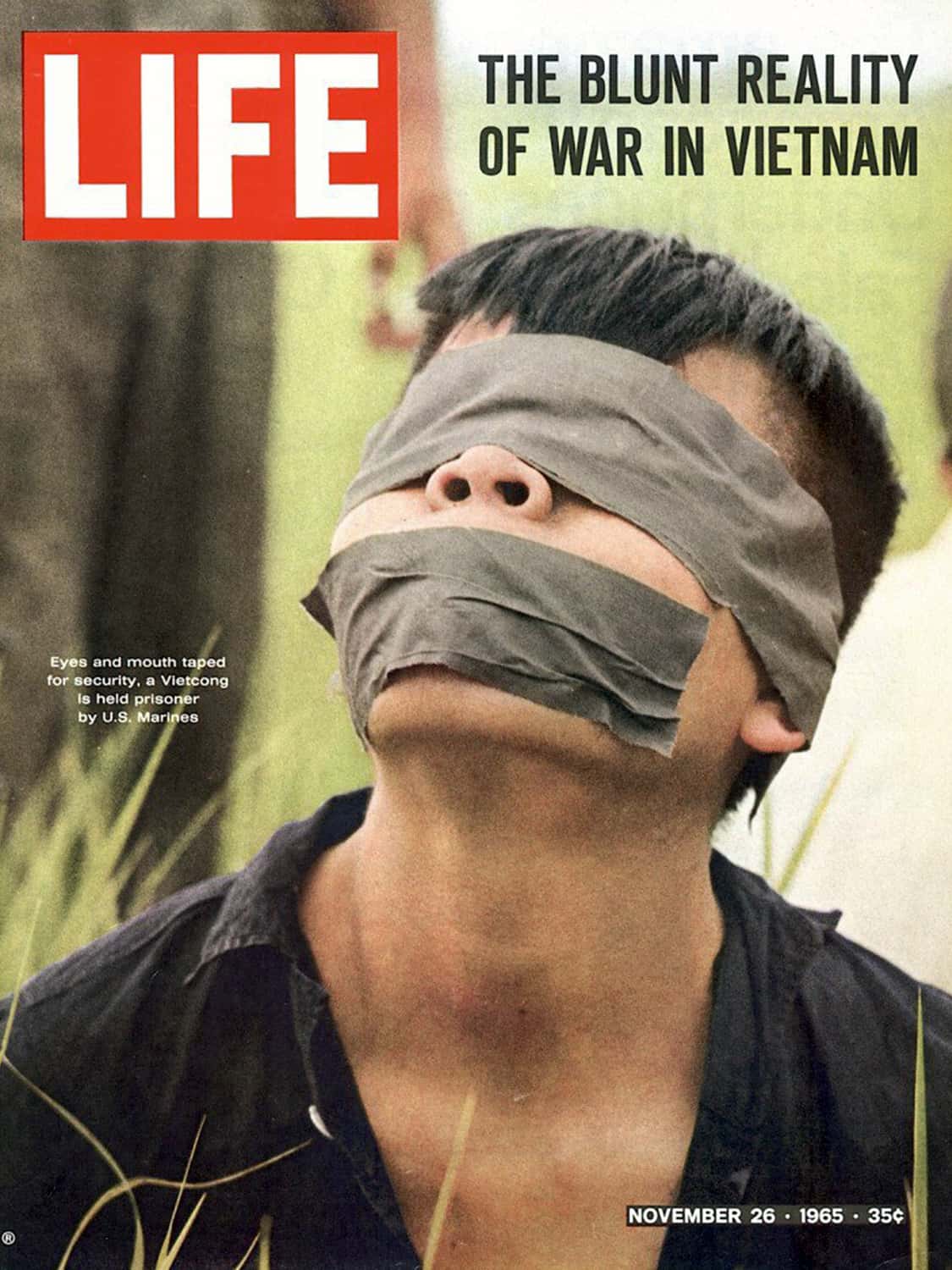

The passion for a career in photojournalism developed later in my life, but had its beginnings in my earliest memories. As a small child, before I could read or be bothered with letting words explain things, I would spend hours looking at magazines like “Time” and “Life.” I grew up in a military family who were historical scholars, and this library exposed me to decades of war images. As warfare tactics changed from WW2 to Korea to Vietnam, I saw the consistent face of humanity in the photos of soldiers who lived and died so far from home.

I would look at the film grain images of young American soldiers ripped apart by battle and cast aside in the mud. And I witnessed acts of heroism between brothers in those frozen pictures. The photographs were powerful, and were taken at great cost. I still clearly see a few in my mind to this day, but mostly I remember what they taught me. I could not look away from history.

We can run from the inconvenient truths of our nation and our local community, but we cannot run from ourselves. Even so, people find a way through entertainment as a form of escapism. That eventually manifests itself in feelings of hate, as a cover for the denied acceptance of feeling fear. Anger can feel like a comforting blanket of safety, except it is extremely toxic and self-destructive. It can be a terminal condition that is not immediate, and the warning signs are masked in the shared solace of others who prefer to drink from the same poisoned well.

Each day when I look at the world, I wonder what it says about who I am and my contribution to it. And it challenges me to make restitution for the sins that I did not commit, but which created the environment I am a beneficiary of. I am reminded by my faith that I am accountable, and how will I answer for my actions this day, and every day?

As a young photographer I traveled the world and those sights remain with me, but many were intentionally never captured on film. They are not exactly haunting, because they do not cause me to suffer, but they are reminders of the things in this world beyond the vision of our local horizon. There were many situations I could not bring myself to photograph, because I did not want to document another person’s misery. Maybe I did not want proof that such terrible conditions existed for people, which made it easier to be indifferent to the suffering of others.

Not long after my life was washed away in the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, I returned to Milwaukee after a decade away. I returned, for what I thought would be a few weeks, basically as a refugee who just happened to still have his passport. As I evaluated the damage from afar and made plans to return to Japan, my father passed away from a massive stroke.

Relationships between fathers and sons can be complicated. I did not follow in my father’s footsteps with a military career, and avoided enrolling in West Point by originally going to medical school. But so many rigid and inflexible views on life were all that my environment surrounded me with. As a kid, I thought every father jumped out of airplanes and blew stuff up. And as a kid with limited exposure to the world, it was all fascinating and normal because every son idolizes his father at that age. What our fathers do often teaches us unspoken values, for things to respect and what to reject.

In Milwaukee, I often find myself covering events that are not comfortable, but I have learned to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. It is still difficult knowing that I am documenting a terrible situation. I do not want to exploit what I see, but neither can I turn away from it. I feel a duty to make a visual record for others. In those emotional moments, no one wants a camera nearby. The memories of that event stay with the participants forever. But not everyone is there to experience it.

News photojournalists were among the migrants seeking refuge at the U.S. border with Mexico, as tear gas canisters rained down around them. Without their dedication, there would be no visual record related to the event. They followed in the tradition of war correspondents who fought for their country with film, recording the ugliest nature of humanity so that future generations might see and learn not love war so much.

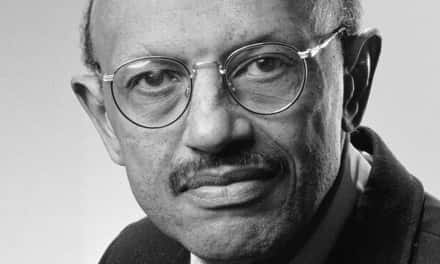

Everyday life is far less dramatic than war, but over time it is every bit as impactful. Everyday life is where we live. The hardest and most surreal personal situation I have photographed was the funeral of my father.

A camera allows me to be in the moment, but also be detached. When my father passed away I never considered photographing the proceedings or how people expressed their grief at the funeral. Yet it was my siblings who took me aside, literally grabbing me by the shirt, and imploring me to photograph the day. They said I was the only person they trusted who could do it, and they understood better than I did at the time why.

So there I sat in the front row as my father was buried with military honors, taking photos of all that happened. I wanted to stop, but I kept telling myself that my siblings asked me to do this, so I had to keep going for them. After the funeral, I put the images together and they have remained private to this day, except for what is being published here for the first time, none of which show my family.

What the day taught me was that my siblings were so overwhelmed with their grief that they did not process much of what was going on around them. Often such situations are a blur as emotions add a fog to the memories. They needed a record of the day to look back at, and was why they asked me to use my skills. Like my siblings, when I think of that day I now think of it through the photos that I took. That was the greatest gift I could give them and the best way I could honor my father. Those photographs are still cherished.

As I look over my photographic career, I find that pictures are how I downloaded many of my memories. Now when I am at events in Milwaukee, where having a camera in hand is considered an insult to everyone around me, and I feel more uncomfortable than anyone possibly could, I think about that cold day when I said goodbye to my father.

It never makes my job easier, but it serves as a reminder that I have an obligation not to turn away from the truth of life in the world that I see around me. I often want to shut my eyes and just walk away, but to do so is the luxury that comes with my privilege. Being able to pick my own assignments means that where I am at is by choice. I cover events that are uncomfortable as a way to challenge myself, because processing those internal struggles are what help shape who I am.

I write this for all the sons who honor the memory of their fathers. It is my wish that others will have the courage to let go of hurt and hate and – most of all – fear, and instead reach for hope. It is harder to do, but we always end up at the truth no matter how long it is obscured.

Neither the world nor the mirror is always a friendly place to look at, but no one can move through an entire life with eyes closed.