It is normal to think that history is remembered in a linear fashion, with people living in the same home their whole lives. They would pass the torch to a new generation and hand down their stories from parent to child to grandchild, honoring the memories and traditions that arrived with each wave of immigrants to settle in Milwaukee and call it home.

Then, somewhere a long the way, the links in that chain of tradition fractured. In the rush for modernization and adaptation, the linchpins of metropolitan life became nails in the coffin of the city’s collective and individual memories.

The history of Milwaukee has been vibrant, alternating between proud achievements and shameful legacies. When the white population en masse decided to use their privileged opportunity to leave the city, their abandonment left an economic vacuum in the wake. Gone too were the social memories as neighborhoods transitioned.

Memories that had been passed down for generations were left behind and forgotten as new lives were forged outside of the city. Those longstanding connections were discarded. From the time the housing flight began in the 1960s as the manufacturing might of the area declined to the early 1990s, Milwaukee experienced and existential identity crisis.

Residents seemed to shun all the things that once made it great. In fact, the population who left and the new one that inherited their void developed an amnesia as a way of coping with their denial and shame of what was lost.

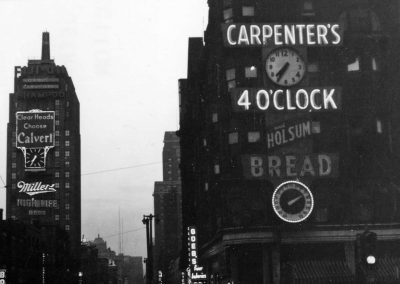

As the Internet age matured and Milwaukee began to restore its luster, the dusty photo albums once discarded also reclaimed their social value. Blogs and social media allowed for the sharing of these digital images, and the exchange of stories surrounding the architectural locations or subjects from bygone eras.

Slowly, those who left Milwaukee could relive the lost memories of a childhood with the romantic nostalgia that so often comes with middle age. Seeing a picture from a location demolished decades ago gave many people a way to share their experiences and recount life during a more simple time.

But youth always remembers their early time as simple. Either because the responsibilities of adulthood have not become a burden or awareness was limited to the day’s fashion, song, or courtships at school. Each generation makes the mistake of thinking that when they were young, American life was far more simple.

A similar distortion comes from old photographs. As adults, area residents have arranged a style of life that is insularly and distant, while keeping enough familiarity to appear interconnected. The same thrill of looking back at a high school yearbook and reliving those glory days becomes amplified by the proliferation of vintage photos.

Milwaukee has developed an unhealthy habit of idolizing the past by sharing historical photographs, and then competing to explore the obscure sites that remain today. The annual Doors Open Milwaukee is a wonderful social event that celebrates the city’s historical architecture. It is an economic and social blessing for the area. But it is also one of the most public and tangible examples of what drives history porn.

Pornography is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the exclusive purpose of sexual arousal. The term applies to the depiction of the act rather than the act itself. Internet pornography viewing is problematic for an individual due to personal or social reasons, including excessive time spent viewing pornography instead of interacting with others.

The mechanism for sharing historical photos about Milwaukee has become unhealthy, both stimulating and dividing those individuals who partake in the experience. Sharing a vintage photo of the Milwaukee Streetcar on social media instantly becomes a toxic troll farm for those individuals who hate The Hop, the city’s new streetcar system. Seeing a photo from the 1930s with a rail-based public transportation vehicle somehow triggers a public meltdown of comments that pits neighbor against neighbor. What began as a simple nostalgic photo presentation erupts into a flame war that serves up political mud slinging and heaps distain on Milwaukee for existing.

Even posting to social media something as beloved as a photo of Billy the Brownie devolves into a conspiracy within three comments. While at the same time, sharing a photo of an obscure location can also set-off a game of one-upmanship. Participants race to identify the spot with their display of logic, memory, and unintended expression of narcissism.

This sharing of photos, while seemingly harmless, allows people to reinforce their selective memories. They already filter the present reality to screen out uncomfortable truths, and these historical photos allow the past to be whitewashed in the same way.

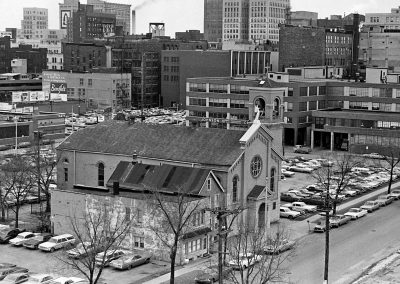

Most of the shared historical images are architectural in nature, which allows every viewer to personalize what they see, because the human footprint is missing. However, images like the Open Housing Marches or suburban KKK and neo-Nazi rallies of the 1960s and 1970s are too divisive. They threaten a perfectly curated historical narrative. If they do inspire nostalgia, it is only for the terrible pride of when one ethnicity held unchallenged dominance.

It seems like many people cherish old photos as a historical record instead of the unseen people and social challenges that existed outside the camera’s view. The current generation of area residents act as if it just discovered all these forgotten relics and are the sole keepers of those legacies. In many cases that is true because so many recollections were abandoned for years. But the knowledge of history has also taken on an elitist “I’m more Milwaukeean than thou” attitude.

The photos of buildings devoid of human beings is like a mirror into our souls. We love things more than we love some people. Memories are valued more than reality.

Historical photographs allow people to remember only the good parts of history, while ignoring the uncomfortable aspects and connections. They are sharable touchstones that preserve the false narrative that people tell themselves. A picture of an old corner grocery store can be revered as a symbol of that neighborhood’s former vitality, while filtering out memories of people who marched past it in protest because they were not allowed to live in that residential space due to the color of their skin or the way they worshiped.

Lifelong history nerds have forgotten more history than most people will ever learn. True historians, like the beloved John Gurda, teach that history is a living thing, always judged and evaluated in the present. But that idea assumes people are actually grounded in the present and not trying to relive the past.

There has also been a growing competition across social media of photographers who are trying to capture the Milwaukee of today. The visual rivalry invents new images instead of trading old ones, but the purpose remains similar. It is a contest to see who can capture the crown of having the coolest image of Milwaukee.

Looking at an old photo will always trigger an associated memory, but it should also inspire a bit of detachment to focus on enlightenment. Instead of racing to publicly sharing private stories as a bloodsport, it would be nice to see people be contemplative and understanding. It would also be refreshing if individuals and groups could step outside their bubble of self-righteous hostility against everyone beyond that shallow sphere, and quit portraying modern Milwaukee as a villain against past Milwaukee as a hero.

The efforts do little to make Milwaukee better. Instead it feeds immediate gratification and foments continued division, with the belief that nothing now can ever be as good as it was in the days of old. That is an unrealistic and unattainable standard. Escapism is how we dismiss the hard questions about history, and our role in it.

Cherishing the simplicity of our childhood never made anyone a better grownup. And usually it is the trauma of youth that haunts most adults. Likewise, the chronicles of Milwaukee should be cherished, but those memories do not make the city better when left in their silo. That is why remembering what business was on what street corner is easier than acknowledging the institutional structure of our community that elevates some, oppresses others, and ultimately fails us all.

History Porn is can be an addiction in every way that corresponds to the stimulus of adult pornography. There is nothing inherently shameful of either, but one is regulated by law and kept directly out of the public space. The insatiable and self-obsessed behaviors surrounding the sharing of historical photos does not rise to that same legal level. But perhaps those who are the most enthusiastic about the hobby should understand the damages done from its public viewing and the discourse it perpetuates.

© Photo

Milwaukee County Historical Society