As a resident of Milwaukee, the daughter of Bruce J. Kremer wanted to see her father’s wartime photographs preserved. That led her to the Milwaukee County Historical Society, and the attention of Assistant Archivist Steve Schaffer.

Schaffer received a call from a donor, asking if MCHS would be interested in a collection of slides taken at the end of the Korean War. Kremer was not a local resident, but his daughter lived in Milwaukee. After Schaffer suggested alternative institutions to give the photo collection, it was mutually decided that MCHS was the best fit.

“I wanted to see the collection in a good home. As an archivist, that is what we do. It is not a competition with one another. So when the donor eventually decided to go with us, and I very thrilled,” said Schaffer. “We have next to nothing on the Korean conflict in our collection, and it has always been a personal interest of mine.”

Schaffer said he often felt dismay at how the Korean War had been forgotten in the American consciousness. That was why he wanted MCHS to have more materials that represented the time. The only other items MCHS has from that era are some personal letters from Milwaukee native John S. Murlaschitz, who wrote his family while a Prisoner of War held in China.

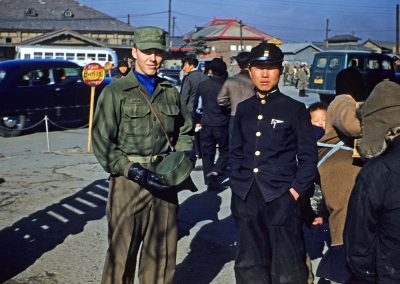

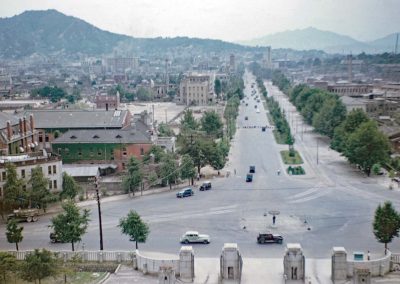

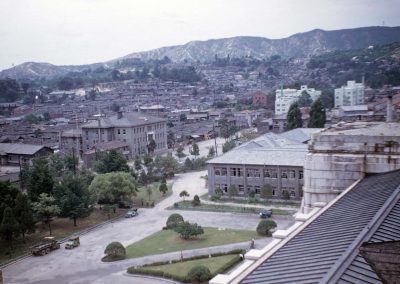

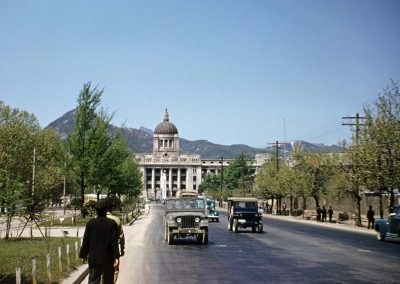

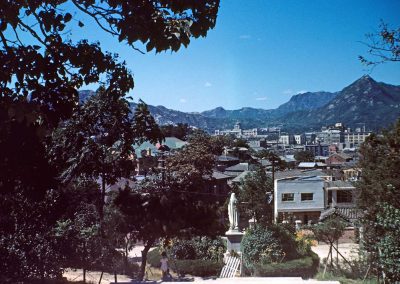

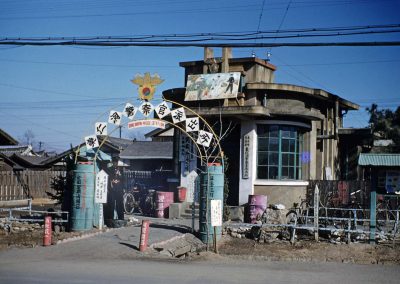

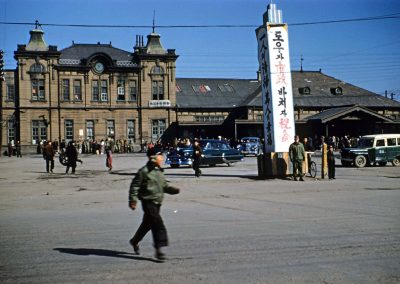

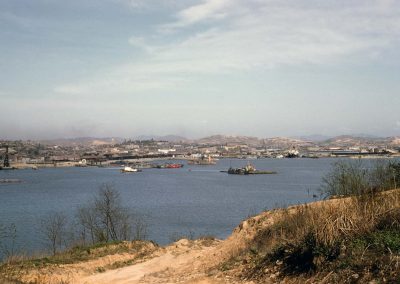

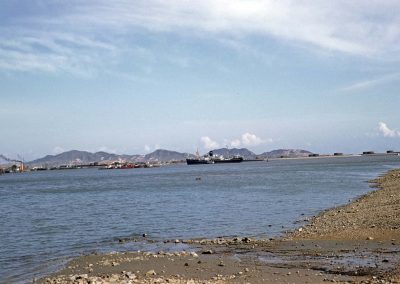

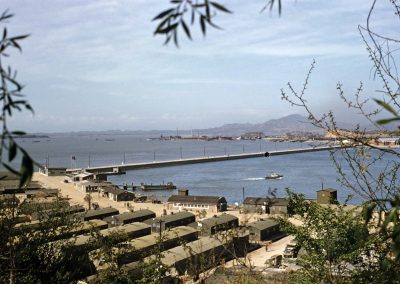

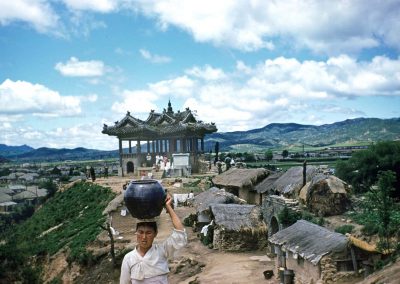

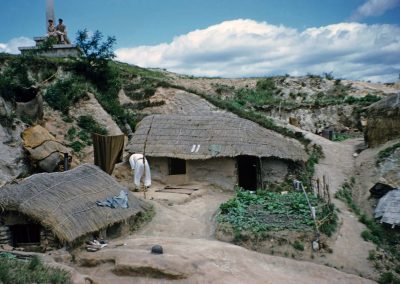

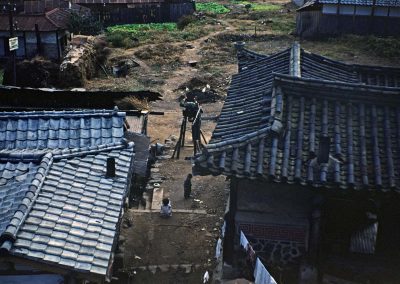

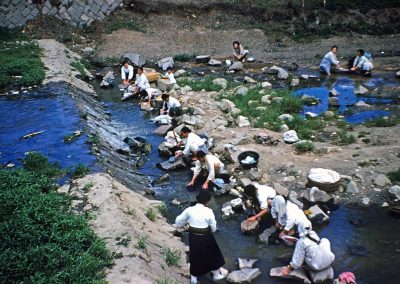

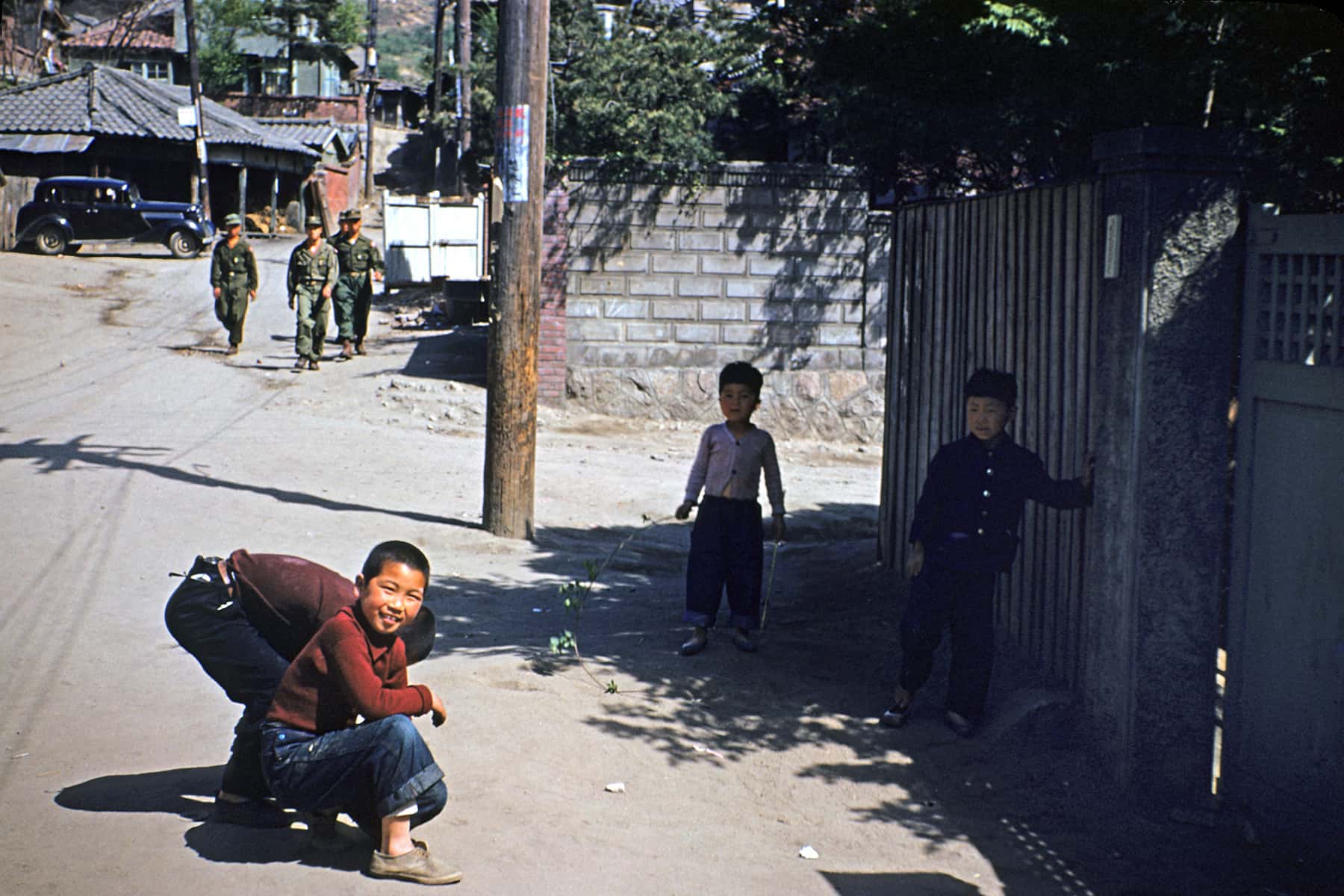

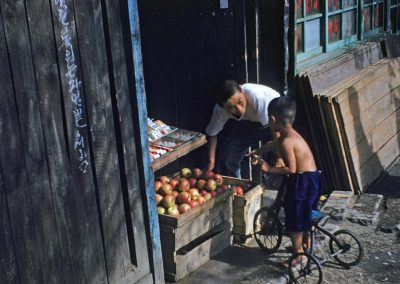

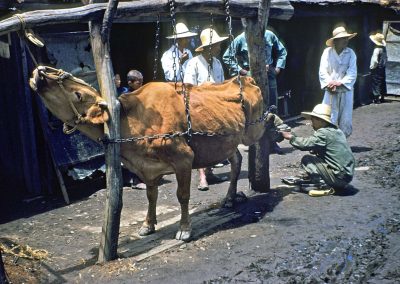

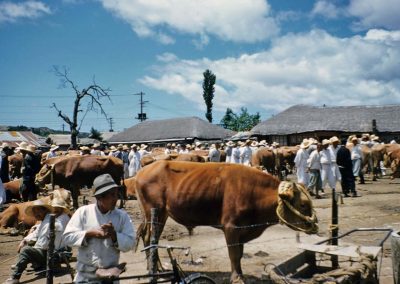

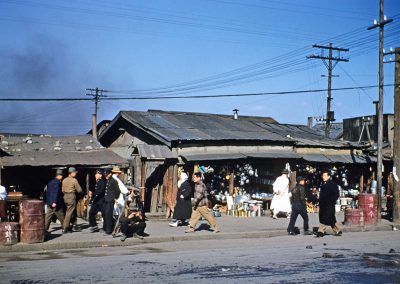

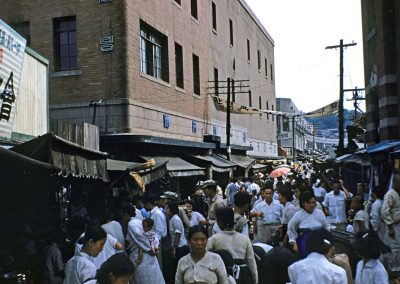

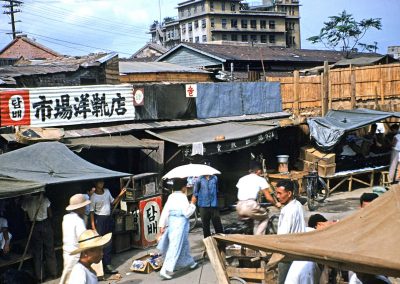

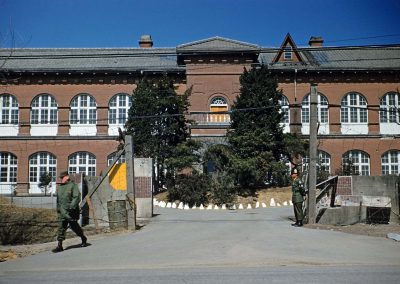

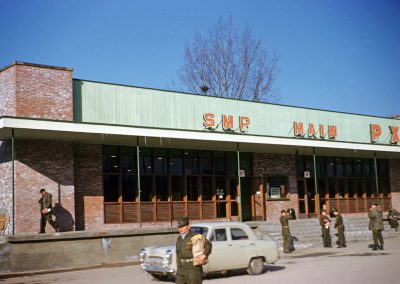

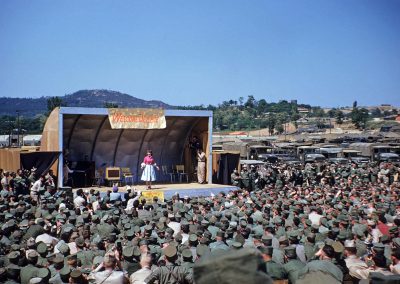

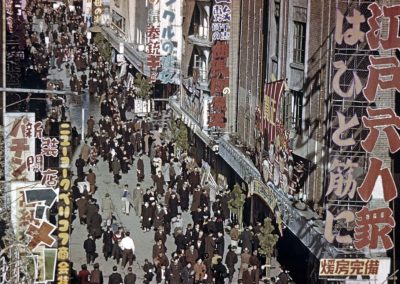

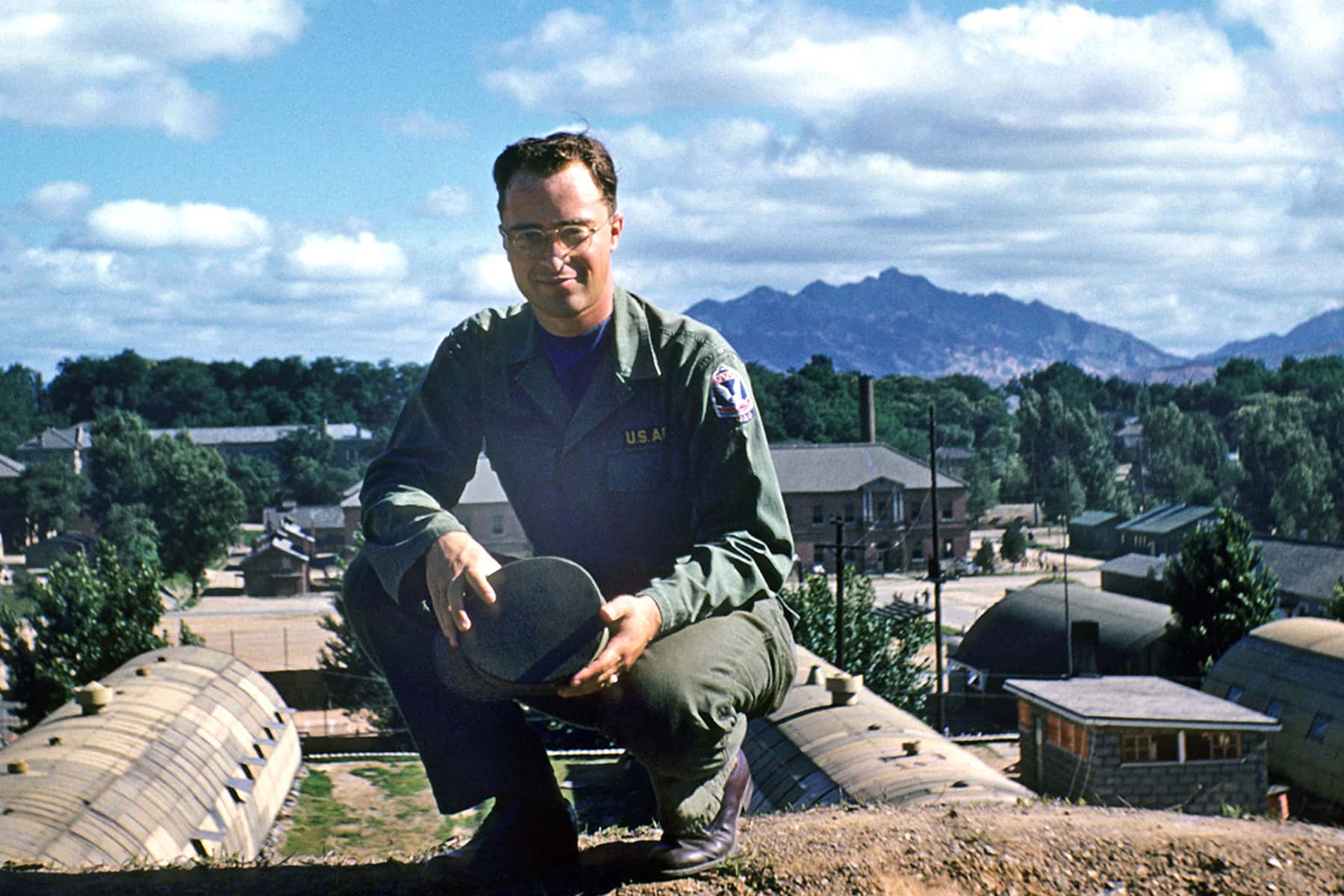

“Kremer’s slides are reminiscent of another collection we have by Lyle Oberwise, when he took photographs in China, Burma, and the India theaters during World War II. These have that same kind of feel to them,” said Schaffer. “They are slice-of-life shots of Seoul and Tokyo in 1954-55, and then some that are related to the military. They are stunning and beautiful, and these type of images in color are very rare.”

The Korean peninsula has been at the center of geo-political struggles for hundreds of years. As Colonial powers sought to carve up Africa and smaller Asian nations, Korea was caught in a tug-of-War between Czarist Russia and Meiji Japan, each trying to wrestle away the vassal of China’s Qing Dynasty. After decades of occupation by Imperial Japan ended with the Second World War, the “the hermit kingdom” was left divided. The two Koreas quickly became the frontlines of first armed conflict of the Cold War between America, Russia, and China.

The Korean War remains less understood today than other American conflicts. Lasting from June 1950 to July 1953, it is estimated that at least 2.5 million people lost their lives. Although history books note that the Korean War ended in 1953, the U.S. Congress officially marks the end in 1955, as a result of the contentious peace negotiations that followed the ceasefire in 1953.

But in reality the war has technically not ended, and a state of hostility has remained for almost seven decades since. The Armistice Agreement only halted the fighting, and no formal peace treat was ever was ever signed. That is why the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at Panmunjom remains one of the most heavily militarized borders in the world.

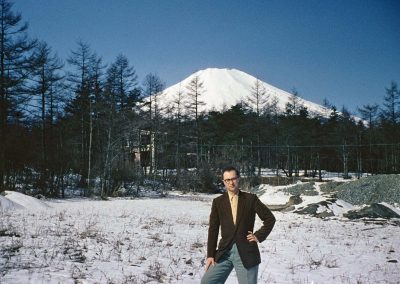

Bruce Kremer’s images from the Korean War were found in a closet by his daughter, containing about 300 Fuji and Ansco 35mm color slides. They showed life on the military base in Seoul, areas around South Korea, and sights in Japan during R&R (Rest and Recuperation). Some information about the images was written on the slides by Kremer.

He also provided a personal narrative about his war service in the U.S. Military. Kremer wrote some of his memories in 1985 and 1986, detailing events for his first grandchild. His story began in December 1953, after he graduated from Mesick Consolidated Schools (MSC).

STORY OF DRAFT AND DEPLOYMENT

“I took a job teaching at a small rural consolidated school system in a place called Mesick, Michigan. During the half year, Gertrude Kline and I began to get to know each other a bit better. Before our relationship could develop very far, however, I received “Greetings from the President of the United States,” the standard letter informing me that I was being drafted into the U.S. Army.”

“The Korean War was still being fought and I would be in the Army for two years. So when the school year ended, Gertrude and I parted friends but with no commitment to each other. In June of 1954, I entered the Army.”

“Basic training took place at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, an old army training base. I was three to four years older than almost all the guys going through the training. I was also the only one in our group to have completed college. After the first part of basic training, which was common for everyone and involved such things as learning to fire and care for a rifle, how to fight in hand-to-hand combat, and the like, the second part of basic training involved being assigned to an area of need within the army. Some people were sent to learn to become med-tech personnel, some airborne, and such.”

“I was sent to ‘secretarial training’ school. You had no choice, you were simply assigned. At the end of the second part of training, assignments were made for the remainder of your military service time – and where it would be spent. Some people were lucky enough to be assigned to duty in the USA. Others got to spend the remainder of their two years of service at stations in Europe. Lists of names with assignments were posted each day on the post bulletin board, with assignments to the USA and Europe being made first. We all read the bulletin board eagerly each day.”

“It was around that time a truce came about in the Korean War. It was an uneasy truce, but at least the major shooting had stopped. My name came up on the list of persons being sent to Korea . I was depressed. I had hoped at least for an assignment in Japan. But the worst assignment of all was to be my lot.”

“We were sent to Seattle, Washington by train – a very old train which was not good enough to be used by civilians. There we spent two days waiting to board a ship for the trip overseas. The troop transport we boarded was one of the largest in the fleet – it carried 6,000 army men plus hundreds of navy personnel.”

“We were the last to board the ship and therefore got the forward most, bottom most compartment – the front end of the ship. The room which was ours had canvass cots piled four deep from floor to ceiling, where we were to sleep and live on the trip. After boarding in the afternoon we all ate a large meal and then the ship headed out of Puget Sound. We sailed into the Pacific Ocean for the trip. The Pacific was, however, anything but passive.”

“We entered immediately into a massive storm with waves so large that they swept completely over the decks of our 600 foot long ship. We were, of course, not allowed out on deck since we would be washed overboard. The storm caused the ship to roll and toss something fiercely and almost all 6,000 army personnel got sea-sick immediately – what an experience. I was sick for one day – others were sick for the entire 21 days that it took us to cross the ocean.”

LIFE ON THE BASE

“We docked briefly in Japan to drop off the men who had been assigned there, and then went on to Inchon, Korea – our destination for landing. There was no usable port at Inchon, so we had to use landing craft to move from ship to land. My assignment was with KMAG – the United States Military Advisory Group to the Republic of Korea Army (USKMAG) – which was located in Daegu, Korea. It was the outfit that provided advice to the Korean Army. It was made up of top level U.S. Army men – generals, colonels, and those of us who would be there to do the support work. I was to be a secretary for one of the generals.”

“After being there only a short time, the KMAG group was moved to Seoul, Korea – the capitol of the country – which was farther north and quite near the DMZ (de-militarized zone). Our operation was located in a group of army quonset huts on the side of a mountain overlooking the Inchon River.”

“We were not allowed to eat anything except that which was prepared on our military base for fear of disease. I also became very active with our church group. We had a chapel on base which was used by various religious groups. I became the organist for the Catholic services held there.”

“Throughout my time in Korea, mail from home was most important. Not only did I get letters from my parents, but also from Gert – who sent ‘care’ packages of home made cookies. We really did continue to build our relationship – even though we were across the world from one another.”

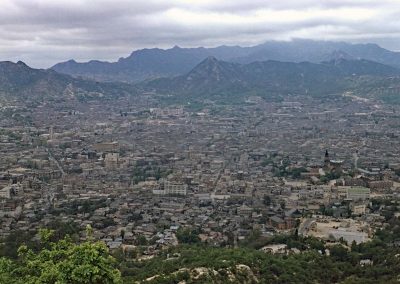

IN AND AROUND SEOUL, KOREA

“Seoul and the rest of the country was in ruins. In Seoul, there were only two buildings left standing undamaged by the war. One was an old temple and the other was a downtown hotel. The capital building itself and everything else was in ruins. “The country was still rather backwards – plowing of the rice fields was done with oxen and wooden plows, for example.”

“My memories of Korea are not fond. The poverty of the people, the black market which flourished, the fact that the Koreans found it necessary to steal in order to survive – even stealing water from the military base. Korea was not a pleasant place to be at that time.”

“One sergeant in our group committed suicide, and another career military man became an alcoholic. The rest of us survived and waited, not very patiently, for the day we could go home. We kept charts on our wall for counting the days until our orders would come to depart. I was in Korea during part of 1954, all of 1955, and part of 1956, getting back home during the summer of 1956.”

REST AND RECUPERATION IN JAPAN

“I developed friendships with several of the other guys stationed there and we took trips into the Korean countryside together when we were able to. We also went on our R&R (rest and recuperation) leaves to Japan together.”

“I remember fondly my two trips to Japan while stationed in Korea. Both were great. I got to see Mount Fuji, the Great Buddha, the city of Tokyo, and loved it all. The people were warm and friendly and there was much to see and do. I bought pearls for my mother and for Gert at Mikimoto’s in Tokyo. We had great fun on the Ginza shopping for souvenirs.”

Schaffer said the Kremer collection was an example of the wealth of images being preserved by MCHS. And while there is a fabulous manuscript collections, he felt that the photos were the real treasure. It is also why he works to continue adding more images from the past, but finds it a challenge at times.

“It’s really hard to get people to understand that their personal photos are history. They say, ‘Why would you want these? They’re just of the house? They’re just of the neighborhood?’ That’s exactly why we want them,” added Schaffer. “It tells a story. It tells something about the 1970s, the fashion from that decade, what the perception of leisure was. All different kinds of historical and social topics are documented in these simple pictures. So I hope people understand that historical photos do not just show City Hall being built, but how regular folks lived.”

- John S. Murlaschitz: Personal letters share Milwaukee soldier’s experience as a Korean War POW

- Emil Kapaun’s Spiritual Heroism: Vatican advances Korean War chaplain closer to Sainthood

- Korean War soldier listed as missing in action for 70 years receives flyover salute during Wisconsin burial

- Saehee Chang: Thoughts on a peninsula at peace with a United Korea

- Milwaukee’s Korean American community reacts to plans for ending the 68 year Korean War

- Professor Nan Kim helps Milwaukee understand the ongoing Korean crisis

- Milwaukee’s General MacArthur and the debate against using atomics in Korea

- Long forgotten Lyle Oberwise photos show life in 1945 Kuomintang China

- Audio: A Milwaukee connection to China-Burma-India during WWII

- “Oberwise in China” gains global attention with Shanghaiist article

- Lyle Oberwise: WWII experiences in Southeast Asia influenced decades of famous Milwaukee photos

Milwaukee County Historical Society