“We are a people who formerly were Africans who were kidnaped and brought to America. Our forefathers weren’t the Pilgrims. We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock; the rock was landed on us. We were brought here against our will; we were not brought here to be made citizens.” – Malcolm X

When the New York Times Magazine launched the 1619 Project, Black people across America shouted, “it’s about time.” We have been waiting for 401 years for the truth of the enslavement of our ancestors to be told on a national scale.

Nicole Hannah-Jones, won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary as a result of her work on the 1619 Project and was attacked immediately. The Pulitzer Center is the 1619 Project’s official education partner. Some historians questioned some of the factual elements of the project but most criticisms were of the conclusions she drew about America and some of its’ greatest heroes. Within the American educational system are embedded ideas about how we should see the world around us. Systemic miseducation is part and parcel of how the system works.

The project team framed the 1619 project by saying this:

“The goal of The 1619 Project is to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year. Doing so requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.”

The project consists of many diverse elements. Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative, wrote an eloquent essay about mass incarceration. Matthew Desmond, best known for his book Evicted, wrote about the history of capitalism and its relationship to slavery. Linda Villarosa wrote about the continuing legacy of myths about the physiology of Black people that contribute to medical inequalities. Trymaine Lee’s essay is about the huge wealth gap in America and how it began with slavery.

Jake Silverstein, the editor of the Times Magazine wrote a rebuttal letter to several well known historians who criticized the project.

“The letter from Professors Bynum, McPherson, Oakes, Wilentz and Wood differs from the previous critiques we have received in that it contains the first major request for correction. We are familiar with the objections of the letter writers…We’re glad for a chance to respond directly to some of their objections. Though we respect the work of the signatories, appreciate that they are motivated by scholarly concern and applaud the efforts they have made in their own writings to illuminate the nation’s past, we disagree with their claim that our project contains significant factual errors and is driven by ideology rather than historical understanding. While we welcome criticism, we don’t believe that the request for corrections to The 1619 Project is warranted. The project’s creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a staff writer at the magazine, has consistently used history to inform her journalism, primarily in her work on educational segregation (work for which she has been recognized with numerous honors, including a MacArthur Fellowship). Though we may not be historians, we take seriously the responsibility of accurately presenting history to readers of The New York Times. The letter writers express concern about a “closed process” and an opaque “panel of historians,” so I’d like to make clear the steps we took. We did not assemble a formal panel for this project. Instead, during the early stages of development, we consulted with numerous scholars of African-American history and related fields, in a group meeting at The Times as well as in a series of individual conversations…As the five letter writers well know, there are often debates, even among subject-area experts, about how to see the past. Historical understanding is not fixed; it is constantly being adjusted by new scholarship and new voices. Within the world of academic history, differing views exist, if not over what precisely happened, then about why it happened, who made it happen, how to interpret the motivations of historical actors and what it all means…As for the question of Lincoln’s attitudes on black equality, the letter writers imply that Hannah-Jones was unfairly harsh toward our 16th president…But she provides an important historical lesson by simply reminding the public, which tends to view Lincoln as a saint, that for much of his career, he believed that a necessary prerequisite for freedom would be a plan to encourage the four million formerly enslaved people to leave the country.”

Many have called slavery America’s original sin. In some ways they are correct. I would argue that the theft of the land we walk on is the nation’s original sin. The two sins worked hand in hand and were parallel journeys in dehumanizing people who the original English settlers saw as different from themselves and therefore worthy of mistreatment.

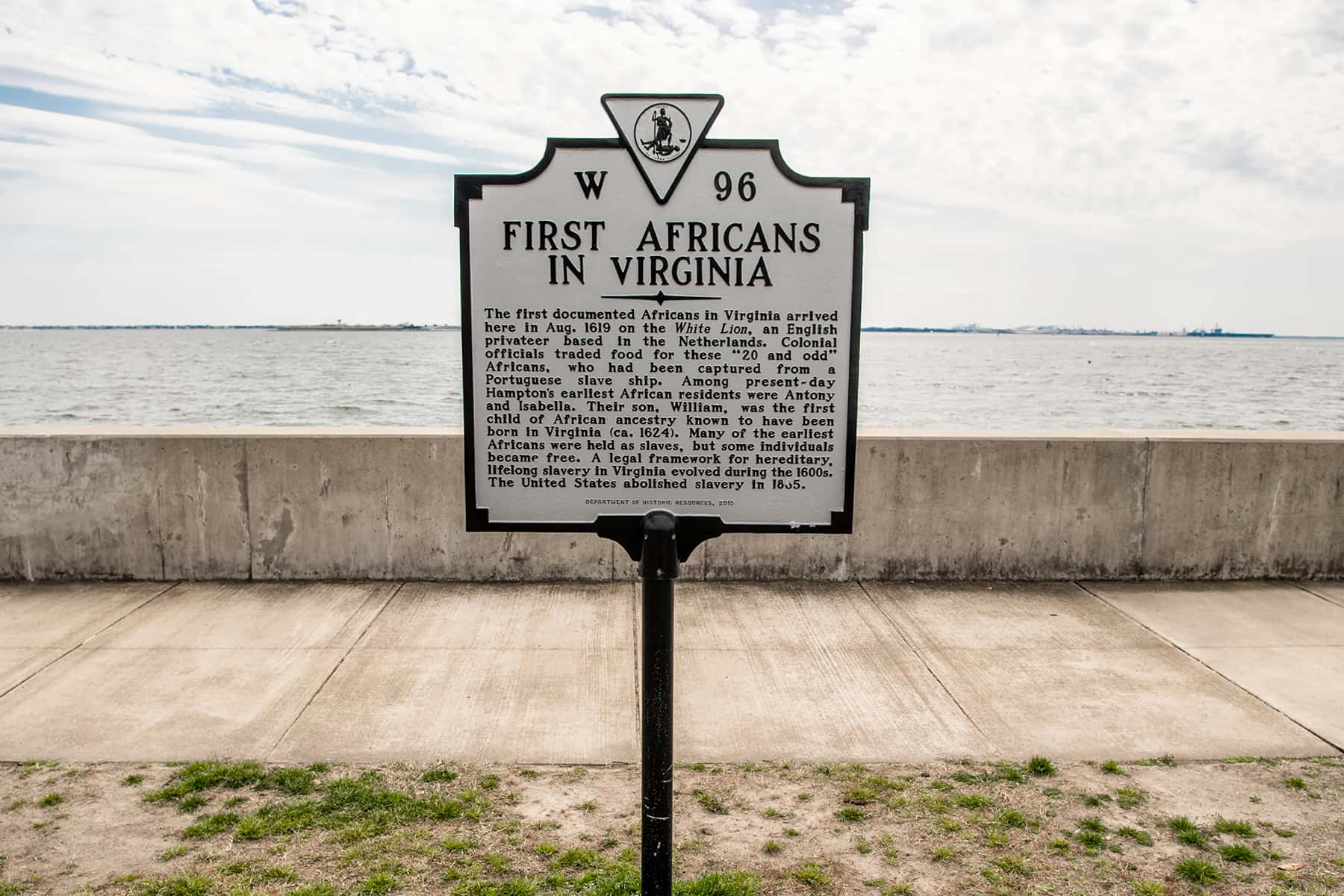

Before the first Africans were brought to Virginia after leaving Angola on a slaving ship, Native Americans had been enslaved in the America’s for over one hundred years. That’s a lot to unpack and I’ll save that for another article.

The first challenge when it comes to talking about the enslavement of Africans is the old, “Didn’t Africans sell their own people” and “Didn’t slavery exist in Africa before Europeans came” arguments. Comparing the form of slavery that existed in Africa before Europeans came and the chattel slavery they introduced to Africa is like comparing 1955 television to 2021 television. In other words, the comparison is ridiculous. This explains the difference.

“Slavery existed in Africa, but it was not the same type of slavery that the Europeans introduced…A slave might be enslaved in order to pay off a debt or pay for a crime. Slaves in Africa lost the protection of their family and their place in society through enslavement. But eventually they or their children might become part of their master’s family and become free. This was unlike chattel slavery, in which enslaved Africans were slaves for life, as were their children and grandchildren.” – Port Bristol Museum.

The first thing to understand is that slavery was a business, conceived and carried out by Europeans with early participation by some Africans who learned the error of their ways too late. The slaveholders from Europe created the market in African bodies.

It began fifty years before Columbus and his crew ran into America by mistake heading to the East Indies. The Portuguese were the first Atlantic enslavers of Africans. They took the first 200 plus West Africans captive in 1444, giving about one fifth of them as a gift to Prince Henry the Navigator.

None of us are taught these things in K-12 school. The role played by the English and by proxy, the United States, is downplayed in almost all of our history classes. Historian Hugh Thomas referred to England as poacher-in-chief because of the number of Africans they transported across the Atlantic before banning the practice.

The main vehicle they used was the Royal African Company. The Royal African Company was established by King Charles II in 1662 and in 1713 they won the prestigious Asiento, a license granting the owner a monopoly on transporting enslaved Africans to the Spanish colonies in the Americas. They held onto this Asiento until 1750. The British Parliament outlawed the trade in enslaved Africans in 1807 but maintained slavery in its colonies until 1834.

According to the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database from Emory University, the English transported 3,259,441 people from Africa and 2,733,324 arrived alive after the Middle Passage on British ships from 1551-1825. That means at least 526,117 Africans died on their ships during the Middle Passage, the horrendous journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

The English colonies and the United States of America were a much smaller player in the trade but transported 305,326 Africans on their ships with 52,674 dying on its slaving ships from 1641 until 1860. The last decade that the trade was legal in this country was 1797-1807. On January 1, 1808 according to the words of the U.S. Constitution, the trade became illegal. It continued despite this mandate. From 1800-1810, 103,922 Africans were kidnapped from their homes and brought to the United States. Only 85,501 survived the journey. Nearly one in five died during the Middle Passage over that timespan.

What is mostly missing in our history classes is what happened once they arrived. We were taught when I was in school that “the slaves were singing in the fields,” “many masters were good people.” Let’s explore each of these. The 1619 Project touches on each of these assertions in some way.

African men, women and children were in those fields working from “can’t see till can’t see” as they called it. They were only there due to violent coercion. None of them volunteered to come to America or any other place outside of their homelands back in Africa. The only true way to understand what it was like is to hear their voices. John W. Blassingame edited the incredible book, Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews and Autobiographies.

Most historians in this country have instead depended on White eyewitness testimony to tell the story of American slavery. First of all, it makes no sense, because there are copious amounts of eyewitness testimony by those who were held captive. Secondly, many Whites, even well-meaning Whites went out of their way to show that American slavery was not as bad as it was. This dishonesty is inexcusable. Two historians in 1971 showed this bias by writing separately that “direct evidence from the slaves themselves is hopelessly inadequate” and “slaves wrote no letters and kept no records.” If we were to accept these assertions we’d never know the truth.

“The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” – South African leader Steve Biko

During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) interviewed formerly enslaved Blacks. The power dynamics in those interviews led to a lot of dishonesty by Blacks who knew that the interviewers were often related to the families that enslaved them.

“Lots of old slaves closes the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery. When the door is open, they tell how kind their masters was and how rosy it all was. You can’t blame them for this, because they had plenty of early discipline, making them cautious about saying anything uncomplimentary about their masters. I, myself, was in a little different position than most and, as a consequence, have no grudges or resentment. However, I can tell you the life of the average slave was not rosy. They were dealt plenty of cruel suffering.” – Martin Jackson of Texas

“Master was a hard taskmaster. I had to work hard, plow and go split wood just like a man. Sometimes they whip me. He whip me bad, pull the close off down to the waist — my master did it, our folks didn’t have overseer.” – Nancy Bouday of Georgia

“Men may write fictions portraying lowly life as it is, or as it is not—may expatiate with owlish gravity upon the bliss of ignorance—discourse flippantly from armchairs of the pleasures of slave life; but let him toil with him in the field—sleep with him in the cabin—feed with him on husks; let them behold him scourged, hunted, trampled on, and they will come back with another story in their mouths. Let them know the heart of the poor slave—learn his secret thoughts—thoughts he dare not utter in the hearing of a white man; let them sit by him in the silent watches of the night—converse with him in trustful confidence, of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” and they will find that ninety-nine out of every hundred are intelligent enough to understand their situation, and to cherish in their bosoms the love of freedom, as passionately as themselves.” – Solomon Northrop, “Twelve Years a Slave” (1853)

Bullwhip Days – The Slaves Remember: An Oral History edited by James Mellon provides more testimony.

“Ole Missus and young Missus told the little slave children that the stork brought the white babies to their mothers, but that the slave children were all hatched from buzzard eggs.” – Katie Sutton

‘…used to sing to nearly everything he did. It was just the way he ‘stressed his feelings and it made him relieved… if he was sad, it made him feel better.” – Vinnie Brunson

“It come to the time Old Master have so many slaves he don’t know what to do with them all. He give some of them off to his children….I was given to his grandson… I see now that I was just a little dog or monkey, in his heart and mind.” – Henry Gladney

I could use many more examples but I’ll stop here because I want people to look for this evidence themselves. The 1619 Project opened a window into American history that some would prefer we not peak into. Don’t be tricked. Don’t be deterred from hearing the voices of the victims and their descendants.

“Until the lion tells its tale the story of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” – African Proverb

© Photo

Lіu Jіе