“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” – Edmund Burke

There has been a great deal of consternation and debate in recent weeks about the Trump Administration deliberately separating thousands of immigrant children from their families. Child advocacy and immigrant rights groups, as well as members of Congress, have expressed their outrage at these inhumane policies being carried out under the direction of customs and immigration enforcement agents. These acts are being directed by President Trump and, per usual, no one is offering any historical context.

This is nothing new for America. The only difference is who the victims are.

For those not well versed in American history, the current actions are somewhat surprising and abhorrent. How could a nation founded on principles, which seem to be the polar opposite of these policies, be so callously taking children away from their parents?

The explanation is simple. We have done it before as a nation.

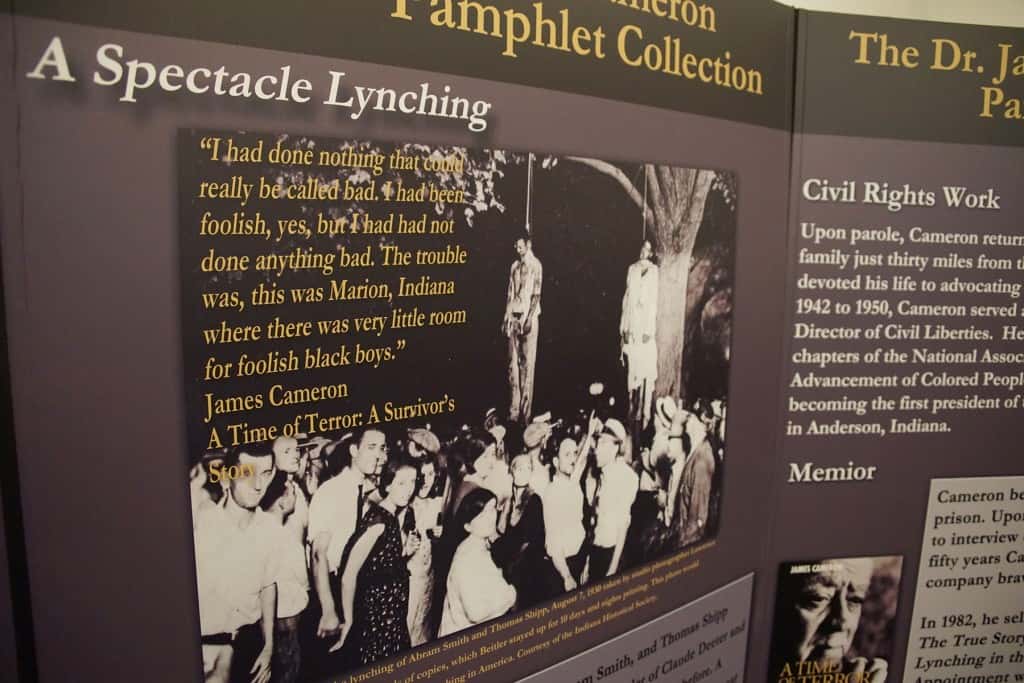

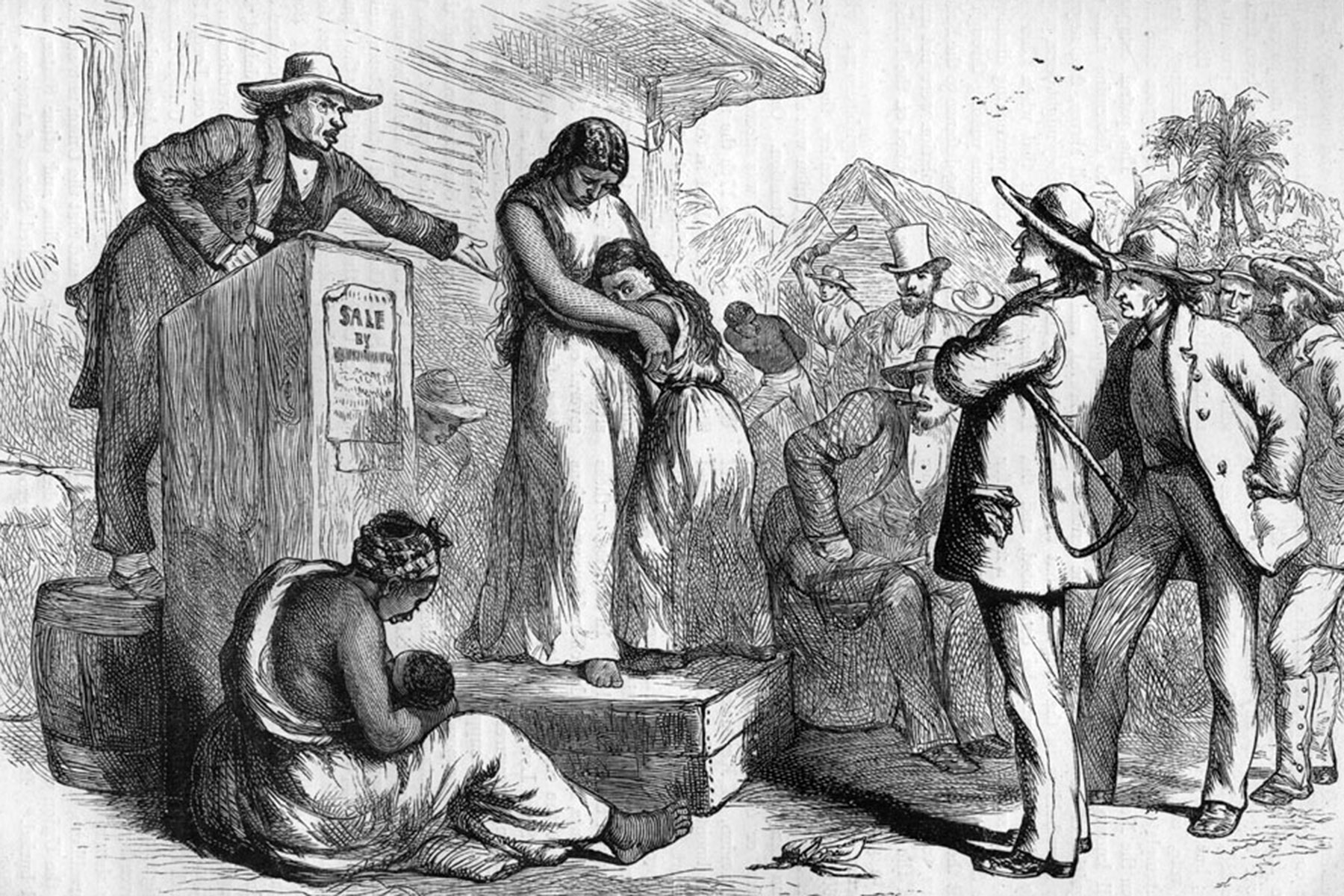

Contrary to what most of us learn in school about slavery, family separation was a constant fear of the enslaved. Slavery put in place a system which punished families regularly by separating parents from their children. In addition to that, for over one hundred years the children of Native American families were taken from them and placed in so-called boarding schools.

When Africans, who had been transported across the Atlantic Ocean, disembarked from filthy death traps we call slave ships, they would be separated from loved ones on the auction block. Whites who wanted to purchase African women, children, and men came to these sales to acquire a commodity that they considered to be less than human.

The sales took place openly in marketplaces from New York City to New Orleans and numerous places in between. The slave markets as they were known would be a place where the building of American wealth would begin. The free, violently enforced labor of millions would be the foundation of America’s economy and the Industrial Revolution.

Slavery was not a Southern institution. All of the thirteen original colonies had laws allowing the enslavement of not only African captives but Indigenous people as well. Slave market auctions would be the first but generally not the last time Africans would be bought and sold in their lives. Slave brokers would buy Africans in “lots” of a dozen or more and go out into the countryside selling them to individual buyers.

As the trade in African bodies grew, the slave markets on the coast of the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico would become feeders for inland slave markets. Africans purchased in Charleston, South Carolina and Virginia would be sold in places as far inland as western Kentucky, and throughout the Mississippi valley. The Africans would be forced to walk long distances shackled to one another as the brokers found new marketplaces to sell their property.

On the initial voyage across the Atlantic during the horrendous Middle Passage, African families had already been separated. The European trading posts like El Mina and Cape Coast Castle in present day Ghana were the depots where families would be permanently severed. On board the ships the Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, Swedes, British, and Americans learned how to lessen the chances of mutinies. They recognized that buying African from different regions lowered the chance that they would be able to communicate effectively, because of the many different languages spoken in West Africa. The slavers began to purchase people in different places in smaller numbers to provide safety and security for the crew.

National security has been used as a justification for separating immigrant families under the Trump Administration. Security was also a rationale for taking Native American children from their families. These children would be placed in isolation from their families, not allowed to speak their native language, and forcibly assimilated into white cultural norms. Just as Africans had been forced to learn to speak English and repudiate their previous names, Native American children were compelled to do the same. Perhaps the children of these immigrants from Mexico and Central America will undergo a similar conditioning today.

When traveling to places like Birmingham, Atlanta, Jacksonville, and other cities where slavery was practiced, the remnants of inland slave markets can still be found. These locations sold millions of Africans and their offspring. Slavery in the northern areas of the country was a different condition than in the Deep South. The sugar cane plantations of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida were treacherous.

The work in sugar cane fields was rife with danger and early death was the norm. Life on these plantations led to a lifespan of ten years at best for many. Children would be forced to work from the age of ten until they died. There were no rules requiring family units to be kept intact.

The old saying about being sold down the river was about the threat imposed on Africans who attempted to escape in the North. Being sold down the river was a dual threat. Not only would you be punished by being sent to the death camps of the Southern plantations, but separation form family would be used to scare Africans into compliance. Despite the fact that slavers argued these Africans had no emotional attachment to their families, they knew from these practices just how important those bonds really were.

There is a special significance to the bond between mother and child. Carrying a baby to full term was difficult during enslavement. Children and their mothers would die prematurely do the lack of proper medical care and an insistence that these women continue to work well into the pregnancy. Once a child was born it belonged not to the mother, but to the slave owner. Laws beginning in the colonial days dictated that the child, whether slave or free, was based on the condition of the mother. Young children could be taken from their mother and father at any given moment at the whim of white families, who saw the child as a piece of property to make them money.

Just as there seems to be a lack of empathy or outrage among the masses of Americans today, about the children of immigrants being taken away, there was none during the historical time either. As we go about our daily lives, thousands of families are suffering one of the most extreme forms of trauma imaginable.

The loss of a child through tragedy is difficult to process. However, the intentional taking of a child is unbearable. We have heard the cries of mothers and fathers for their children over recent weeks, as this story has become more widely known. We have heard that somehow thousands of these children have been “lost” in the bureaucratic red tape that the federal government is so infamous for.

How can we stand by as a “Christian nation” and allow this? Are people less than human because they are not American citizens?

Once again, because we have done this before. There was little to no outcry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when a massive number of children were taken from Native American parents. Hundreds of thousands of children were forcibly pulled away from their parents and placed in “schools.” The founders of the schools had the audacity to call them boarding schools. Officially they were known as Indian Residential Schools in the United States and Canada.

The purpose of removing these children from their families was to cut them off from their familial and cultural ties. I prefer to call them assimilation camps. The children would be forced to learn and assimilate European values, education, language, and ways of dressing as well as behavior. Such places in China during the brutal Cultural Revolution were know as re-education camps.

Native American children were not allowed, at the expense of severe punishment, to speak any of their indigenous languages. Shouts of “learn to speak English,” barked by rabid anti-immigration supporters today, harkens back to the same principles that were required at these camps. They were originally set up throughout the West by different Christian churches. Eventually the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs would establish more camps based on a systematic assimilation policy.

Just as Africans were given European names, these native children would be as well with the particular addition of surnames. They were forbidden to wear their hair in any format other than traditional European styles. Abuse was the order of the day in these camps. Physical, mental, and sexual abuse was widespread. Attendance at the camps continued to grow throughout the twentieth century. Enrollment reached a peak of about 60,000 in the early 1970s.

The Civil Rights Movement among native Americans led to the dissolution of this horrific policy by the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. Most of those schools were not permanently closed until the late 2000s.

“Boarding schools embodied both victimization and agency for Native people and they served as sites of both cultural loss and cultural persistence. These institutions, intended to assimilate Native people into mainstream society and eradicate Native cultures, became integral components of American Indian identities and eventually fueled the drive for political and cultural self-determination.” – Dr. Julie Davis

The famous orator and anti-slavery advocate Frederick Douglass used the forced separation from his mother as a tool to drive his desire and eventual escape from enslavement. With the official ending of slavery at the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in December 1865, the march was on to find lost family members. Children would look far and wide for missing parents and other relatives. Mothers and fathers would desperately try to reconnect with the children who had been stolen from them.

Most these efforts were futile. Name changes were common in this period and the old plantations were destroyed during the war. Families were forced to find new places to live. Many blacks fled the South, moving to the North and other regions for a fresh start.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, established in March 1865, assisted many in finding family members. However, it was disbanded in 1872 by the federal government after being gravely underfunded and undermanned for years. The work was impacted by a lack of financial support, as well as violent attacks by whites on the formerly enslaved people and the bureau workers.

As blacks like myself attempt to trace our family histories, we are confronted with an understanding that it will be impossible to fully stitch our family’s past together. Enslaved blacks were not listed by name in the U.S. Census until after the Civil War in 1870. It was very difficult to maintain a family history because of the fact that families would be separated time and time again.

Just as mothers are having children ripped out of their arms by Immigration agents today, African children were snatched away by slaver traders.

These parallel journeys of current immigrant families, Native Americans, and Africans and their kin folk remind me that they all had one thing in common. They were people of color.

As has been the case too many times before, our white fellow citizens have stood by and watched for the most part. Whites still own the power and control of most American institutions, including our federal government. Most members of Congress are white.

It is imperative that those who hear these stories understand the tremendous harm being done to children and their families, and put a stop to it immediately. People of color cannot do it alone. Our voices are but a whisper competing with the boisterous rhetoric of anti-immigration groups emanating around an self-isolated Congress and an intolerant White House.

“In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.