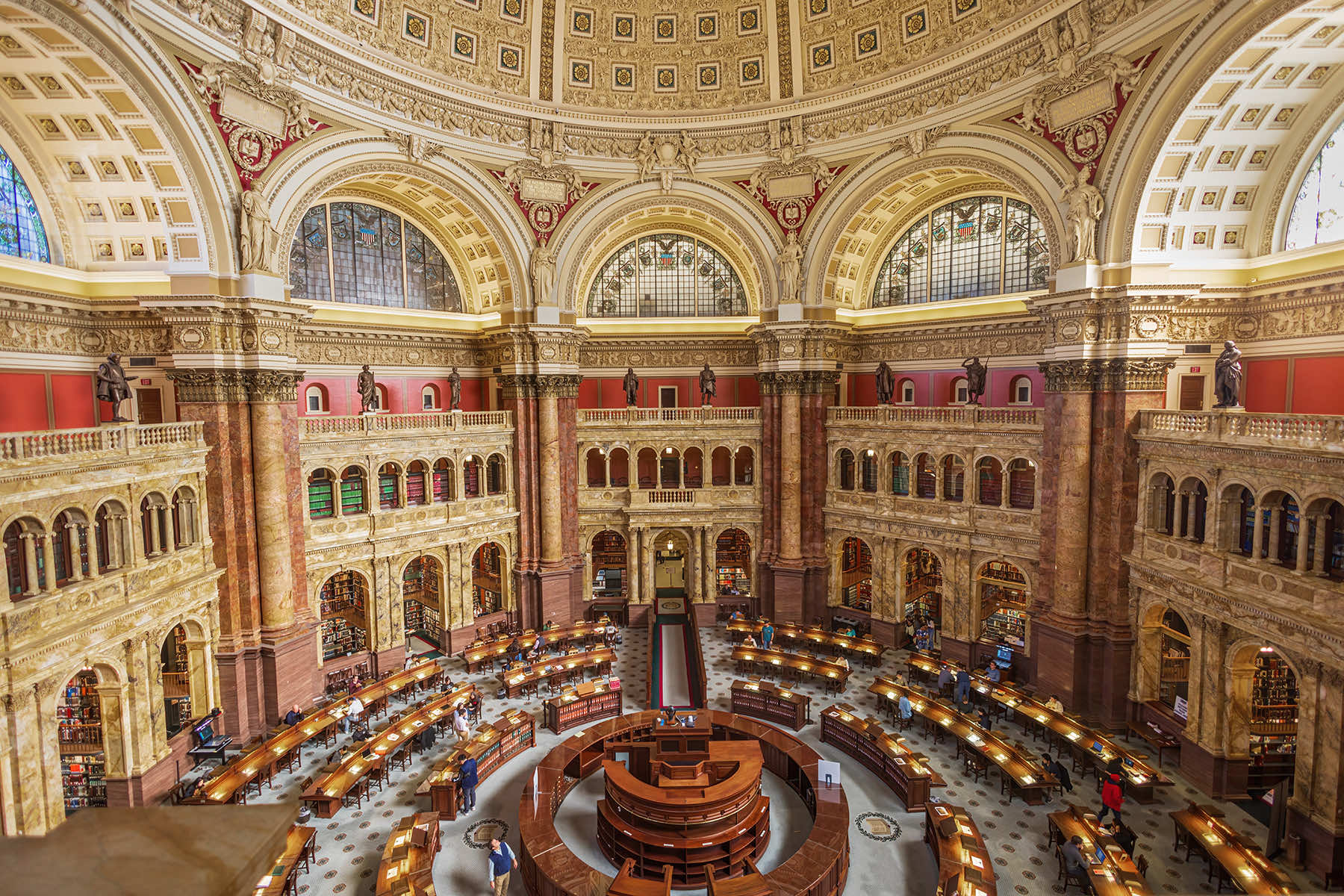

In a stately repository of the nation’s heritage, two volumes rest quietly among countless others. These books, housed in a prominent American library dating back to the country’s earliest years, speak to a complex and often overlooked facet of the nation’s founding era.

The English translation of the Qur’an was once owned by an influential Founding Father. The other manuscript was authored by a Muslim scholar forcibly brought to North America as an enslaved individual.

The manuscripts challenge the commonly told narrative of America’s religious liberty and progress. Taken together, the two surviving texts suggest that Islam’s influence in early America was not a distant footnote but a subtle and significant presence woven into the nation’s foundational tapestry.

Many histories of the United States highlight the country’s Enlightenment roots, its struggles for independence, and the visionary documents that cemented its democratic ideals. Yet, accounts of Islam’s role in the process have remained in the margins.

The presence of the Qur’an in the personal library of Thomas Jefferson, a principal architect of the Declaration of Independence and the third president, is more than a curious historical anecdote. It stands as evidence that American founders, in their pursuit of knowledge and global understanding, considered Islamic thought among the many intellectual currents shaping their own evolving views on governance, religious pluralism, and the nature of freedom.

Jefferson’s Qur’an came into the public spotlight more recently, in 2007, when an elected representative — the first Muslim member of Congress — chose to take a private oath of office upon it.

The event surprised most Americans who did not realize that an influential founder studied the Islamic text, suggesting a worldliness and openness to non-Christian faiths at the very start of the nation’s journey.

The founders were products of a time when educated Westerners sought familiarity with a broad spectrum of religious and philosophical writings. Works on Islamic history and scripture were not obscure to them.

To such intellectuals, the Qur’an represented a significant religious and legal tradition that had helped shape large swaths of the Old World. Understanding the Muslim faith could yield insights into law, governance, and human rights — areas in which the fledgling republic sought to chart a new course.

Jefferson purchased his English translation of the Qur’an in 1765 while still a student of law. His personal library featured a broad range of material, extending far beyond the Bible and classical Western writings.

According to historical evidence, he was deeply interested in comparative religion, political systems, and legal traditions. Reflecting an era increasingly aware of global affairs, Jefferson and his contemporaries were no strangers to Islam’s presence on the world stage.

British interactions with the Ottoman Empire, as well as North African states and other Muslim-majority regions, had already integrated Islamic scholarship and governance models into European consciousness.

The American founders inherited these connections and wrestled with what religious inclusivity might mean for a new republic. It was not merely a theoretical exercise. They understood that in acknowledging the rights of conscience, they might one day include people of faiths then considered foreign.

These founders, though revolutionary in their philosophical outlook, were still very much tied to the social hierarchies and contradictions of their time. One glaring dissonance was the reality that while they contemplated religious freedom on a grand scale, the institution of slavery remained deeply rooted in the nation’s economic and social fabric.

It was a system that did not simply import human labor from Africa, it also brought African cultural and religious traditions onto American soil. Among the millions of enslaved Africans who arrived in North America, a significant number were Muslims.

They carried with them memories, names, languages, and religious practices dating back to Islamic communities in West and Central Africa. Despite the brutal suppression of their freedoms, these enslaved believers tried to maintain their faith as best they could.

The presence of enslaved Muslims in early America is not speculative. Primary sources confirm it, including slave inventories containing names that echo Islamic heritage and autobiographical documents written in Arabic by these individuals themselves.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence is the story of Omar Ibn Said, a West African man who was a teacher of Islamic law and theology before his capture and enslavement. Transported to the United States during Jefferson’s presidency, Omar Ibn Said left behind a memoir written in Arabic.

His words reflect a devout Muslim intellectual enduring the dehumanizing conditions of enslavement in a land that prided itself on liberty. For historians, his writings serve as an invaluable window into the lived religious experience of enslaved Muslims and the intellectual legacy they carried into the Americas.

That juxtaposition, Jefferson’s intellectual interest in Islam and the harsh reality experienced by enslaved Muslim Africans, highlights the profound contradictions at the heart of the nation’s founding. Even as Jefferson drafted legislation that laid the groundwork for religious freedom, including a famed Virginia statute championing the free exercise of faith, he enslaved hundreds of individuals over the course of his life.

He envisioned a republic where followers of all religions, including “the Mahometan” as Muslims were often called, could one day be citizens. Yet, countless Muslim Africans remained subjugated and denied any notion of equal rights or religious liberty. The moral contradiction points to the complexity and fragmentation of early American ideals that were noble in theory, but frequently failed in practice.

During Jefferson’s presidency, the United States engaged diplomatically with Muslim-majority states, notably from the Ottoman sphere and North Africa. In 1805, the first Muslim ambassador to the United States, hailing from Tunis, visited Washington DC. Jefferson reportedly recognized that his guest was observing the Islamic month of fasting, Ramadan.

Adjusting a state dinner to accommodate the sunset breaking of the fast was a subtle but notable gesture. It also signaled a diplomatic respect for Islamic practice at a time when non-Christian religions had scarcely any public acknowledgment within American political life.

The act might not have been a grand statement of religious pluralism, but it demonstrated that, to a degree, Jefferson’s intellectual familiarity with Islam translated into respectful consideration for Islamic customs when the necessity arose.

Still, these moments of recognition were exceptions rather than a rule. For the countless enslaved Muslims, the founding era offered little practical opportunity to practice their faith without fear. Enslavement often stripped people of their religious texts, community structures, and the freedom to gather.

Adherents of Islam maintained their traditions through covert prayers, oral transmission of knowledge, and quiet acts of resistance. Over time, many African-born Muslims and their descendants had little choice but to assimilate into a cultural and religious landscape dominated by Christianity, either voluntarily adapting or being forcibly converted.

The cultural memory of the Islamic faith persisted in fragments. Prayers were whispered, rituals continued in secret, and Arabic writings on scraps of paper, which planted seeds of religious diversity that would not fully blossom until centuries later.

The legal foundations set forth by Jefferson and other leaders eventually paved the way for today’s Constitutional protections of religious freedom. Modern American Muslims have cited this long-standing legal principle when asserting their rights to worship freely, participate fully in public life, and hold elected office.

When Keith Ellison, the first Muslim member of the U.S. Congress, took his private oath of office on Jefferson’s Qur’an, the gesture carried a powerful symbolic weight. It linked the contemporary Muslim-American experience back to the nation’s founding philosophy and to the founder who had once examined these Islamic texts.

Ellison’s decision signified the ongoing struggle for inclusivity, as well as the remarkable fact that Muslims are not newcomers; their presence has been threaded through the national narrative since its earliest pages.

The story of Islam in early America prompts a re-examination of commonly taught histories. Traditional narratives have often focused on European religious influences and the dominance of Protestant Christianity in the colonies and the early republic. Yet, a more nuanced understanding emerges by recognizing the cultural and religious diversity that existed from the start.

Reflecting upon these intertwined stories, American society today can gain a more accurate picture of the early republic. The recognition that Islam had a seat, however small and contested, at the table of early American thought challenges simplistic portrayals of the founding generation. It also encourages a broader understanding of the global influences that shaped the United States.

Islam has deep roots in the nation’s earliest days, illustrating that the promise of inclusion and the reality of exclusion have always coexisted. Such recognition can serve as both caution and inspiration, guiding current and future efforts to realize the lofty principles upon which the “American Experiment” was founded.

© Photo

Orhan Cam, Orhan Cam, Alexandre F. Fagundes, Framalicious (via Shutterstock)