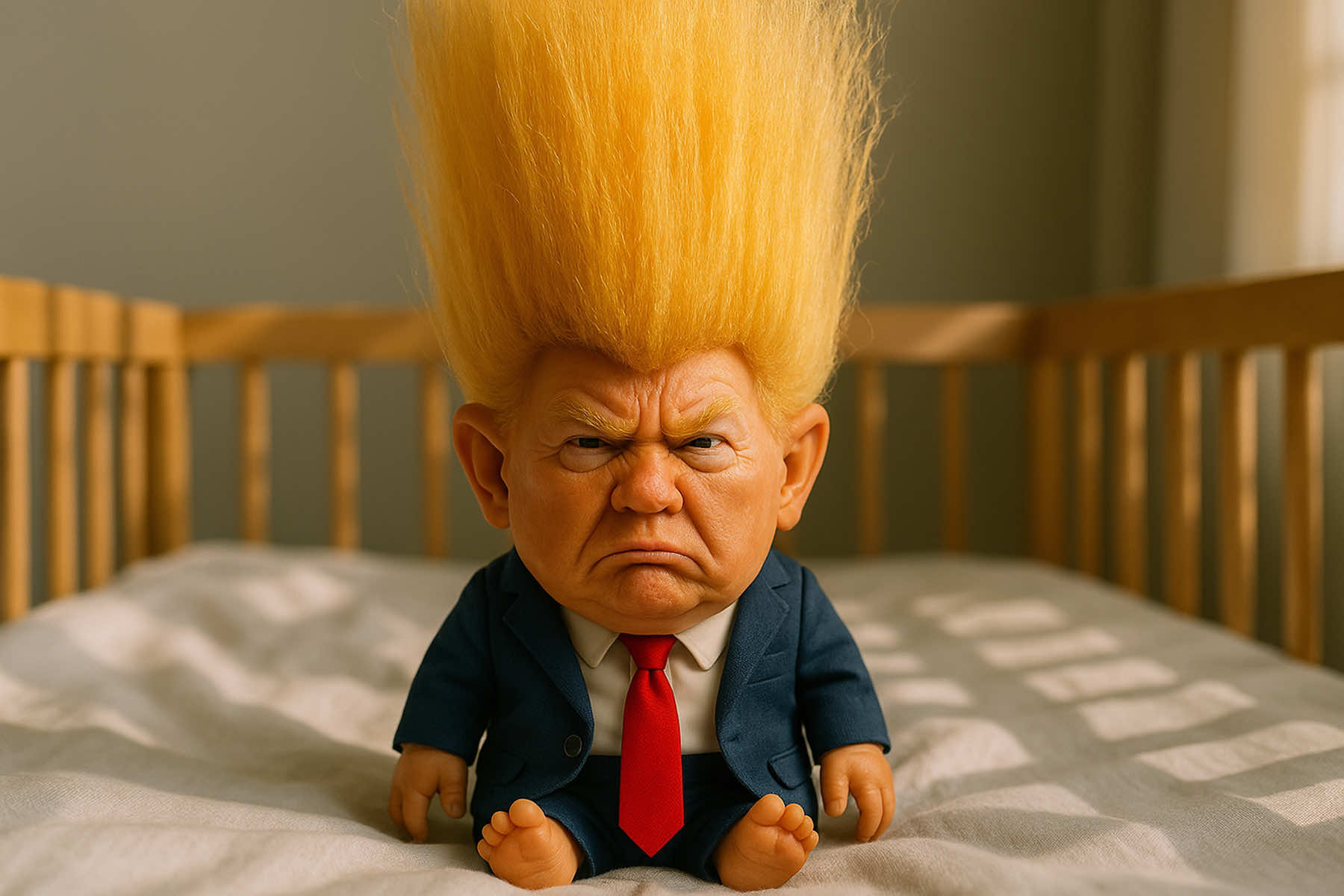

This AI-generated image is a photorealistic editorial illustration and not an actual photograph. It was created to support a journalistic commentary as a political cartoon.

The term “domestic terrorist” carries legal, political, and cultural weight in the United States, typically reserved for individuals or groups who threaten public safety or the functioning of a democratic society through violent or coercive means.

But recent years have expanded the debate: Can a sitting president of the United States, the nation’s highest elected official, meet that definition?

Under U.S. federal law, the definition of domestic terrorism is not ambiguous. According to Title 18 of the U.S. Code, Section 2331(5), domestic terrorism involves acts that are dangerous to human life, violate criminal law, and are intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, influence government policy through intimidation or coercion, or affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping — provided the conduct takes place primarily within U.S. territory.

Historically, this definition has applied to organized groups, lone actors, and ideologically motivated movements. However, experts in constitutional law and national security policy have increasingly raised concerns that executive power itself can be wielded in ways that meet these criteria.

The focus of this debate has centered on Donald Trump, whose post-election conduct in 2020 and actions since returning to office have triggered comparisons to the statutory framework for domestic threats. A comprehensive review of events, language, and outcomes reveals a disturbing pattern that many legal analysts argue warrants scrutiny under the very laws typically applied to extremist actors.

The January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol remains a flashpoint in this discussion. That event involved a coordinated, violent effort to disrupt the certification of electoral votes. It was an attack that led to deaths, injuries, and widespread disruption of government operations. While Trump was not formally charged with terrorism-related offenses, the conditions surrounding the event — including prior incitement, refusal to intervene, and subsequent glorification of the attackers —have raised questions about culpability and intent.

Several individuals convicted in relation to the Capitol attack have cited the president’s rhetoric as a motivating factor. In other contexts, such a relationship would be grounds for prosecutorial review under domestic terrorism laws.

Beyond January 6, Trump’s use of federal law enforcement to suppress dissent during protests, authorize extrajudicial detentions, and threaten civilian populations with state violence further deepens concern.

During periods of civil unrest in Trump’s first term, federal agents were deployed in cities without coordination with local governments, using unmarked vehicles and force tactics more typical of military operations.

These actions, while justified by administration officials as crowd control, bore the hallmarks of coercion intended to intimidate not only protesters, but also political opposition and the public at large.

Moreover, the coordinated campaign to delegitimize the electoral system — including pressure on state officials, attempts to install false electors, and efforts to overturn certified results — reflects not just political defiance but an operational strategy to undermine lawful governance.

The weaponization of fear also played a central role. From public threats against prosecutors, judges, and civil servants, to the encouragement of supporters to take “revenge” against political enemies, the messaging from the executive office has repeatedly crossed into territory that legal experts equate with psychological warfare.

The sustained climate of intimidation — including doxing, harassment, and implicit threats — has had measurable impacts on the willingness of public officials to perform their duties without fear.

When courts delay action out of concern for public backlash, when prosecutors require security details, and when elected officials refuse to speak publicly due to safety risks, the line between political expression and domestic terror begins to dissolve.

The legal standard for domestic terrorism does not require an ideological label. It requires conduct — acts of coercion, intimidation, or violence — that seek to reshape public behavior or government action.

When institutional power is used to shield this conduct from consequence, the legal system itself is placed in jeopardy. Prosecutorial discretion, judicial independence, and legislative oversight depend not just on the letter of the law, but on the capacity of institutions to act against those in power.

This institutional paralysis is not new. Democracies around the world have faced similar moments, when heads of state begin to centralize authority, undermine electoral legitimacy, and normalize the use of force or fear to maintain control.

In the current environment, the challenge lies in the unwillingness of other branches of government to confront executive overreach when the conduct in question mimics the very behavior those institutions were designed to prevent.

If acts of political violence, coercion, and systemic intimidation are ignored or reclassified as policy disputes, then the definition of domestic terrorism becomes elastic — applied to fringe actors but never to those at the center of power.

If the law is enforced only against the powerless, it ceases to be law at all. And if domestic terrorism statutes are used against dissidents or protesters while excluding those who command state power and incite public unrest, then the moral authority of that legal structure collapses.

Public reaction remains divided. For some, accusations of domestic terrorism against a sitting or former president appear hyperbolic, politically motivated, or legally tenuous. For others, the pattern of behavior — spanning incitement, intimidation, and institutional manipulation — presents a textbook example of domestic extremism, masked by political legitimacy.

If a president uses the mechanisms of government to incite fear, destabilize public trust, and advance personal power through threat-based tactics, then the behavior itself — not the office — determines the classification. The definition of domestic terrorism is about means and ends, not political identity.

Critics of inaction argue that failing to confront this reality effectively normalizes domestic terror when it originates from the executive branch. They point to the chilling effect on civil society, the increase in threats against journalists, the politicization of federal law enforcement, and the erosion of democratic norms as symptoms of a deeper, systemic crisis — one where violence or the threat of it becomes a feature of governance.

Legal analysts have underscored the need for a clear and consistent application of domestic terrorism statutes. If intimidation campaigns, politically motivated threats, and coordinated interference with democratic institutions are not met with enforcement, then the same actors — unrestrained by consequence — will escalate further.

There is no statute that prohibits the president of the United States from being labeled — or prosecuted — as a domestic terrorist if the evidence supports it. The political ramifications are complex, but the legal standard remains unchanged.

If executive power can be used to threaten, coerce, or terrorize without consequence, then the boundaries between governance and authoritarianism collapse. The issue is no longer what label is applied, but what conduct is tolerated — and what future that tolerance enables.

This AI-generated image is a photorealistic editorial illustration. It is not an actual photograph and does not depict a real situation. The image was created to support commentary protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution as a form of political expression. Its use is consistent with established legal precedent, including the Supreme Court’s decision in Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988), which affirmed that satire and parody involving public figures are protected forms of speech and are not considered defamation unless containing knowingly false factual assertions made with actual malice.

ChatGPT-4o