Like most kids growing up in the 1980s, I knew about the Korean War from documentaries and school books. But it mostly existed in my awareness from watching the TV show M*A*S*H, which was still broadcasting when I was young and also re-run in heavy syndication. Even though it was a story about doctors at a mobile hospital in the Korean War, everyone said the series was a proxy for the Vietnam War. I also conflated that distinction. It seemed like there was always something trying to divert or overshadow public attention from anything related to Korea.

I remember my shock and bewilderment when I learned that North and South Korea were still technically at war. My boss told me about it one summer while I was working at a print shop, during my sophomore year of college. How had that fact never been taught to me in school?

The Korean War, as far as I am concerned, was a Third World War – but confined to the Korean Peninsula. Soviet Russia, China, and the U.S.A. were all allies in 1945. By 1950 they were openly killing each other. A total of 21 countries contributed forces to the United Nations Command in Korea. A total of 30 countries were directly involved in World War II, either as part of the Allies or the Axis powers.

The 1980s was a time that saw a dramatic increase in children adopted from Korea, and it seemed like I always had a friend at school from Korea. After college, a Korean American friend told me about how hard it was for her to fit into American society. She was born in Seoul but moved to Milwaukee at 8 years old. She said that Koreans saw her as too American, and Americans saw her as too Korean – which was her way of saying she would never be seen as White.

Years later when I found myself living as a minority in Asia, and then returning to Milwaukee after being overseas for one-third of my life, I always kept her words in my mind. They often helped me process whatever the culture shock was that I experienced. I was too White to ever fit into the Asian societies where I had lived. But in Milwaukee, I felt too connected to an Asian identity to fit into White society.

Korean people and Korean culture have always been a part of my life. But like a waiter at a restaurant, they are both seen yet ignored – remaining invisible. I have used the same analogy about being a photojournalist, everyone sees me but thankfully no one really pays attention to me. For my work, that condition is necessary. But it is unacceptable for people trying to fit into a dominant culture.

I first visited Korea in 1996, when I took a sabbatical to circumnavigate the globe. I was already planning to visit countries like Japan, China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Germany. I could not travel to those countries, then come back and explain to my Korean friends how I was unable to visit South Korea.

It would be like going from Wisconsin to Michigan and somehow not passing through Illinois on the way. Out of respect, curiosity, and the fear of feeling guilty if I did not go to Korea, I added Korea to my trip. It was a wonderful experience to visit Seoul, Incheon, and Suwon.

A few years later, I found myself living near the city of Dandong at the border with North Korea, along the northern part of the Yellow Sea. The area sat directly across the Korean Gulf, or the Liaodong Bay as it was known in China.

I was there when North Korea conducted its first successful nuclear test on October 9, 2006. The test was detonated underground in a location called Punggye-ri in the northeastern part of the country. Kim Jong Il would not visit China after that for another 4 years, until May of 2010.

His arrival was confirmed when he was seen at a hotel under tight security, after his heavily armored train had crossed the border into Dandong. My late wife had an office at the hotel, and her company sent her home for the day before his arrival. I knew he was coming before any media announced it.

China’s President Hu Jintao traveled with Kim back to Beijing for discussions on reviving the stalled six-party talks about North Korea’s nuclear programs, and the sinking of a South Korean patrol ship in late March of that year.

I lived very close to Korea for a decade, but I never managed a return visit until this journalism assignment in September 2024. Where I lived had a huge density of ethnic Koreans, displaced originally by the Japanese occupation or the subsequent civil war. In fact, I ate more Korean food in China than I did Chinese food.

It was kind of like the old saying about being a tourist in your hometown. Korea was so close, and I was surrounded by Korean culture, that making an actual visit was not a priority. But to be fair, re-entry visas for China are super difficult, so for 8 years I never visited anywhere for fear of being unable to return.

I have reported on issues involving Korea as a journalist over the years from Milwaukee, and shared many of my own experiences in personal essays. But I never wrote what I would describe as anything substantial, beyond a handful of topics.

For the past two years I have taken several overseas assignments with connections to Milwaukee, including the war in Ukraine (twice), Mexico, Jordan, Jerusalem, Türkiye, Poland, and Japan. My third assignment to Ukraine in October 2023 was delayed due to October 7, and I was on standby for many months to go with a Milwaukee medical team to Gaza.

I did try in November 2023 to take an assignment to Korea, but the project did not get a lot of support. And around that time I began preparing for two assignments in 2024. A return to Ukraine in May or June, and Vietnam in October.

Through my connections with Vietnam War veterans, I was introduced to Le Ly Hayslip. Her 1989 memoir, “When Heaven and Earth Changed Places,” caught the attention of Oliver Stone and inspired his 1993 film “Heaven & Earth.”

> READ: Waging Peace: Le Ly Hayslip reflects on 35 years of humanitarian work with Vietnam War Survivors

She invited me to visit Vietnam with her. It only made sense for me to go if I could bring a Vietnam veteran along. I had only one name in mind, and approached George Banda about the idea. He had never been back to Vietnam since the war, and had never thought about going. We knew that many veterans have returned over the years to bring closure and healing to their experiences there, but from our research we could not find any veterans from Milwaukee who had made the journey.

His decision to go with me was a big deal for many reasons, and I spent weeks planning the trip. Until everything fell apart. Le Ly’s schedule changed, so she had to go in August instead of October. George and I had August commitments and could not travel during that time. We considered alternative options, but ultimately felt it was better to abandon the idea. I think it was ultimately a bit of a relief for both of us that it did not work out.

Then my plans for returning to Ukraine with a shipment of tech supplies from Milwaukee derailed in May, due to shipping delays and funding issues with the humanitarian group I would be embedded with. I found myself with an open calendar for the rest of the year, for the first time in two years, and with funding for at least one last overseas trip connected to Milwaukee.

I had always regretted not visiting Ukraine prior to the full-scale Russian invasion, when I had the chance to document so many cities before they were destroyed. But no one at that time believed Russia would actually start a war.

I still have no crystal ball for the future, and with the November elections I could not travel overseas past October. That was back when President Joe Biden was still the Democratic candidate, and I did not want to be out of the country if things melted down. Of course, if Trump somehow won and began persecuting journalists as he promised, a part of me considered trying to stay out of the country until after the election just to be safe.

In May, I sat down and thought about what could be the next Ukraine, excluding the Middle East. The North-South Korean issues and situation with Taiwan were nothing new and those tensions have been playing out for decades. I do not expect things to suddenly change.

But I knew there would be a lot of uncertainties surrounding the November elections. Missiles would not fly, but bad actors could use the window to play at brinksmanship. An assignment to Taiwan and South Korea (and the DMZ), with connections back to Milwaukee, felt like the best option.

I wanted to use the time before anything could actually happen to construct a thoughtful and accurate narrative. With few if any comprehensive resources in the news from Milwaukee, I felt the work would be important if breaking news and ignorance started playing hard and fast with the truth, especially in an increasingly anti-Asian environment.

North Korea was also heavily involved in supporting Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and I was intimately aware of the China vs. Taiwan issues. So a lot of good connections to the journalism I had been involved with.

Ultimately the logistics of Taiwan were just too ambitious. And plans for Korea were still very tentative. I had lost contact with many of the Korean friends of my young adulthood, but I knew of Korean War veterans, and one veteran in particular who served at the DMZ in the 1980s.

It was the bare minimum to do a very basic series connecting Milwaukee with Korea. But I wanted to do more, and I really needed help. My research efforts in November 2023 were minimal and left me feeling discouraged, but I was willing to start over fresh and try again. After many eMails and overseas calls, all my leads in Korea fell flat so I pivoted back to Milwaukee. The resources here were the most obvious, but perhaps even harder to develop.

A few more weeks of trying and my efforts stalled again. I was about to give up for good on the idea. Then I reached out to Korean churches in one last attempt. And it turned out to be the jackpot that opened every door, and the project expanded exponentially beyond what I could have imagined.

Production of the special series took off, with the intention to explore historical sites and cultural traditions from across the Korean Peninsula, building a bridge back to Milwaukee. From the occupation of Korea at the end of World War II, to Korean War veterans in Milwaukee, veterans from Milwaukee who served in later years at the DMZ, adopted South Korean children who grew up in Milwaukee, and different waves of the South Korean diaspora who moved to Milwaukee to raise their families, it would weave together generations of Milwaukee voices and Korean experiences.

My aim before starting the assignment was to produce about 36 articles after I came back from Seoul. I felt that was really ambitious, and I was not even sure I could find that many things to write about – including people to interview. By the end of August, before I even left for Seoul, we already had 48 features and 15 interviews finished.

I could never have imagined that the series would eventually total 72 features. With 21 interviews and 51 articles, supported by 2,200 photos and 117,000 words – the equivalent of almost two young adult books.

So many articles were completed that I technically no longer needed to travel to Korea to finish the series. But I still felt everything had to be authentic, and how could so many issues about Korea be reported on without visiting Korea?

I do remember thinking at one point that I had to go to Korea to just take a break so I could stop reporting. It was like a “Dr. Strangelove” subhead … “Exploring Korea or: How I went to Korea to take a break from writing stories about Korea from Milwaukee.”

In Seoul, one of the first disappointments we encountered was being unable to visit the Joint Security Area (JSA) at Panmunjom. I had heard about its temporary closure last year, but the South Korean government and tourism companies kept that fact quiet, and continued to publicly advertise DMZ tours they knowingly could not fulfill.

I felt it was very disingenuous to sell access to a site that no one can access, then divert people to secondary locations. But that was the situation, so we made the most of the opportunities we had to access what was available. Going to Panmunjom was strictly a photo opportunity. I had been there before, and I had photos, so it was not hard to pivot. In fact, it opened up better opportunities that might otherwise been neglected.

Panmunjom was a symbol of history, confrontation, and the potential for peace. It was the embodiment of the ongoing tension and fragile ceasefire between North and South Korea. As the focal point for diplomatic efforts, it remains a remembrance of the unresolved conflict on the Korean Peninsula. For Milwaukee, it also represented the deep and shared connections between the city’s Korean War veterans and the Korean American community.

The trip helped me to answer a couple of technical questions, what did Koreans call the Korean War and why did South Koreans always drop “South” when talking about Korea?

Koreans typically refer to the Korean War as Yugio Jeonjaeng (전쟁), which translates to “the 6.25 War.” The name comes from the date the war began, June 25, 1950. The war is also sometimes referred to as Hanguk Jeonjaeng (한국 전쟁), meaning “the Korean War,” when speaking to foreigners.

Koreans, Korean immigrants, and Korean Americans all refer to South Korea simply as Korea. The “South” is an important distinction between it and the “North.” However, my impression was that it reflected more than just a vernacular habit. Americans are very clear when talking about North Dakota or South Carolina.

As I considered references and context for when to add “South” if it was not mentioned in an interview, I came to a simple – if controversial – conclusion. In the minds of South Koreans, South Korea is the real Korea, a true successor state of the historic Korean nation. So there is only Korea, and then North Korea was the part that broke off. I am sure that the North Koreans would have an inverted view of that observation, and strenuously reject my counter conclusion.

I think the best argument for why South Korea is the successor state goes back to 1910. Seoul was the capital of Korea when the Empire was annexed and placed under Japanese colonial rule. During the years of occupation, the Japanese also recognized Seoul as the nation’s capital. While the country was divided in half by external powers after World War II, North Korea refused to re-unify with the Korean state in the South. It then launched an invasion, which should technically be considered a civil war, with the help of foreign powers. It may be a semantical stretch to say North Korea broke off from the true Korea, when the country was externally split in half. But North Korea’s violent and bloody provocations in 1950 should disqualify it from “Successor State” status.

My team and I also had the good fortune to be in Korea for two historic dates, one by accident and the other by design. The only day we could visit Incheon was September 15, which turned out to be the 74th anniversary of General Douglas MacArthur’s historic amphibious landing. I visited the actual spot where he personally stepped ashore, now rather far inland after years of sea reclamation and landfill. We also entered Jayu Park (Freedom Park) during a very jubilant public ceremony honoring the anniversary and surviving veterans.

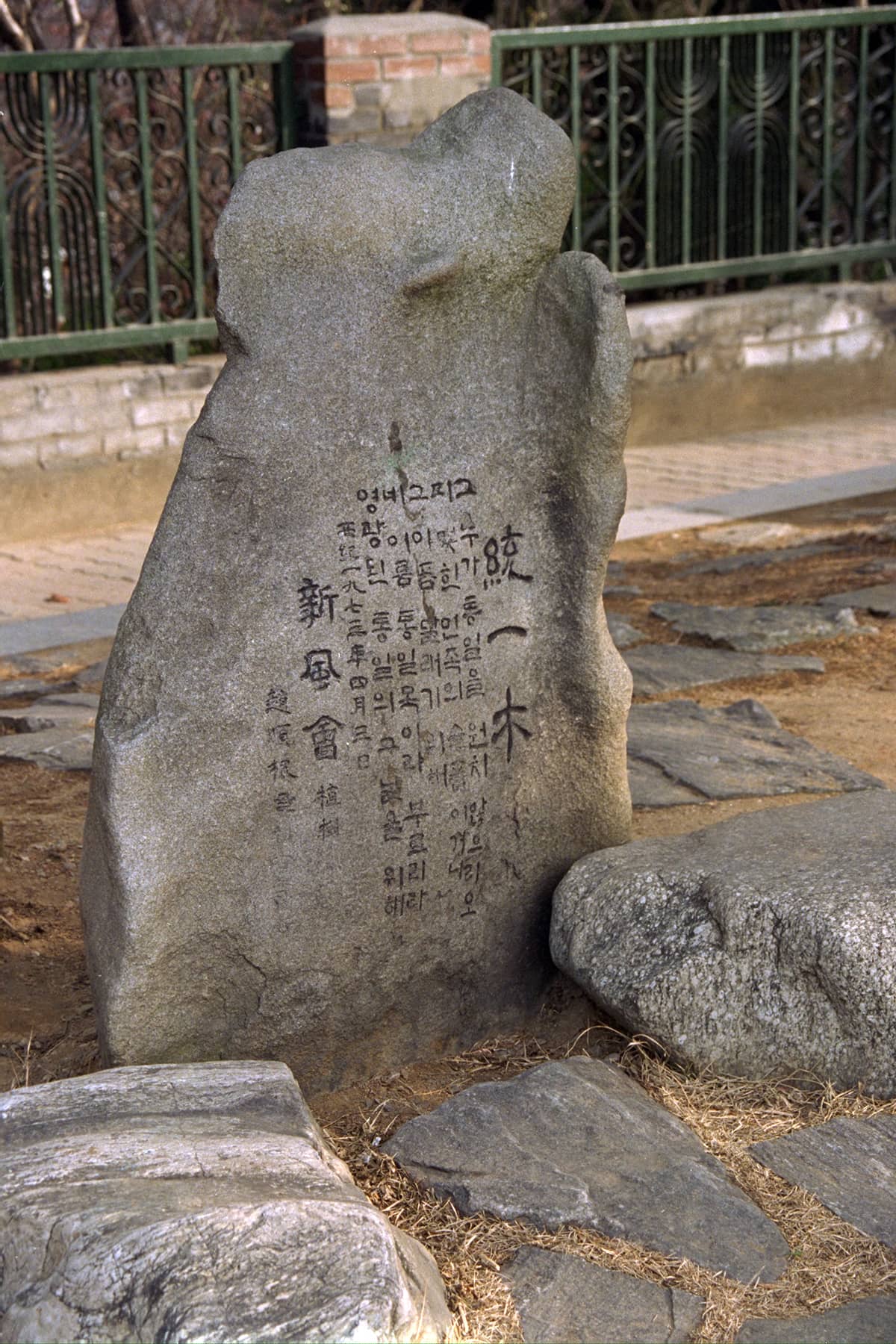

There was one photo that I took of General MacArthur’s statue in 1996 that I never saw anyone else reproduce in the years since. When Milwaukee relocated our own General MacArthur statue in 2015, I did a lot of research about it and never came across a picture that showed his statue offset by a large stone historical marker.

When I arrived at the site of his statue in Jayu Park, I forgot where I had stood to get the alignment. The crowd was so big I thought that they and the event tents would obstruct the stone marker and prevent me from recreating the shot. But as I wandered around the perimeter, I realized where I needed to be. There is only one place that a person can stand to get the shot that I did, and while it is not obscure it is not very obvious at all.

Another reason I originally picked the spot in 1996, which I realized in 2024 when I stood there again, was that the foundation of the marker stone blocked the crowd perfectly. General MacArthur’s statue was so tall, and there was a perfect alignment to get that shot without seeing anyone else. I had originally taken the photo in a vertical orientation using a film camera. Now in a digital world, with the Internet dictating horizontal formats for editorial photos, I made the wide shot work. But I did go back and crop it to a verticle image to show side-by-side the 1996 and 2024 versions.

For the Chuseok (추석) holiday, that was marked on our calendar. It was a privilege to be there for such an important celebration, but not without the frustration that comes with overcrowded and overzealous post-pandemic tourist crowds.

Chuseok, South Korea’s version of Thanksgiving, marks a major cultural celebration focused on family, tradition, and gratitude for the harvest. Held on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, it is a time when families gather to honor their ancestors with rituals like Charye (차례), a memorial ceremony, and Seongmyo (성묘), a visit to ancestral graves.

A key part of the holiday is sharing Songpyeon (송편), a traditional rice cake filled with ingredients like sesame or chestnuts. Chuseok is more than just a holiday, it is a reflection of deep-rooted cultural values centered on family and community.

The biggest change I saw between 1996 and 2024 in South Korea was running into foreigners everywhere, especially outside of Seoul. They were fairly rare in my previous and limited experience. Aside from Seoul’s modernization, which was obvious to see but a bit fuzzy in my memory for comparisson, I discovered a distinct change of attitude about Seoul.

In 1996, it was a separate city from Incheon. Now, Seoul has expanded so far that Incheon had been absorbed like a suburb. Personally, I think Seoul as a city is more like Milwaukee County from an administrative viewpoint, or even Tokyo as a megacity that manages smaller districts.

But aside from all the municipal distinctions, Seoul was the absolute center of the South Korean universe. To be sure, it still is but not exclusively so like it had been before. While I did not get to explore beyond Incheon and Suwan in 1996, I was told by everyone I met that there was basically Seoul and then every place else. Seoul was the city, the rest of South Korea was the countryside. I was young and could only understand what I could see, so I was not in a position to evaluate how realistic such statements were. I believe there was truth at the core, but also a lot of Seoul superiority too.

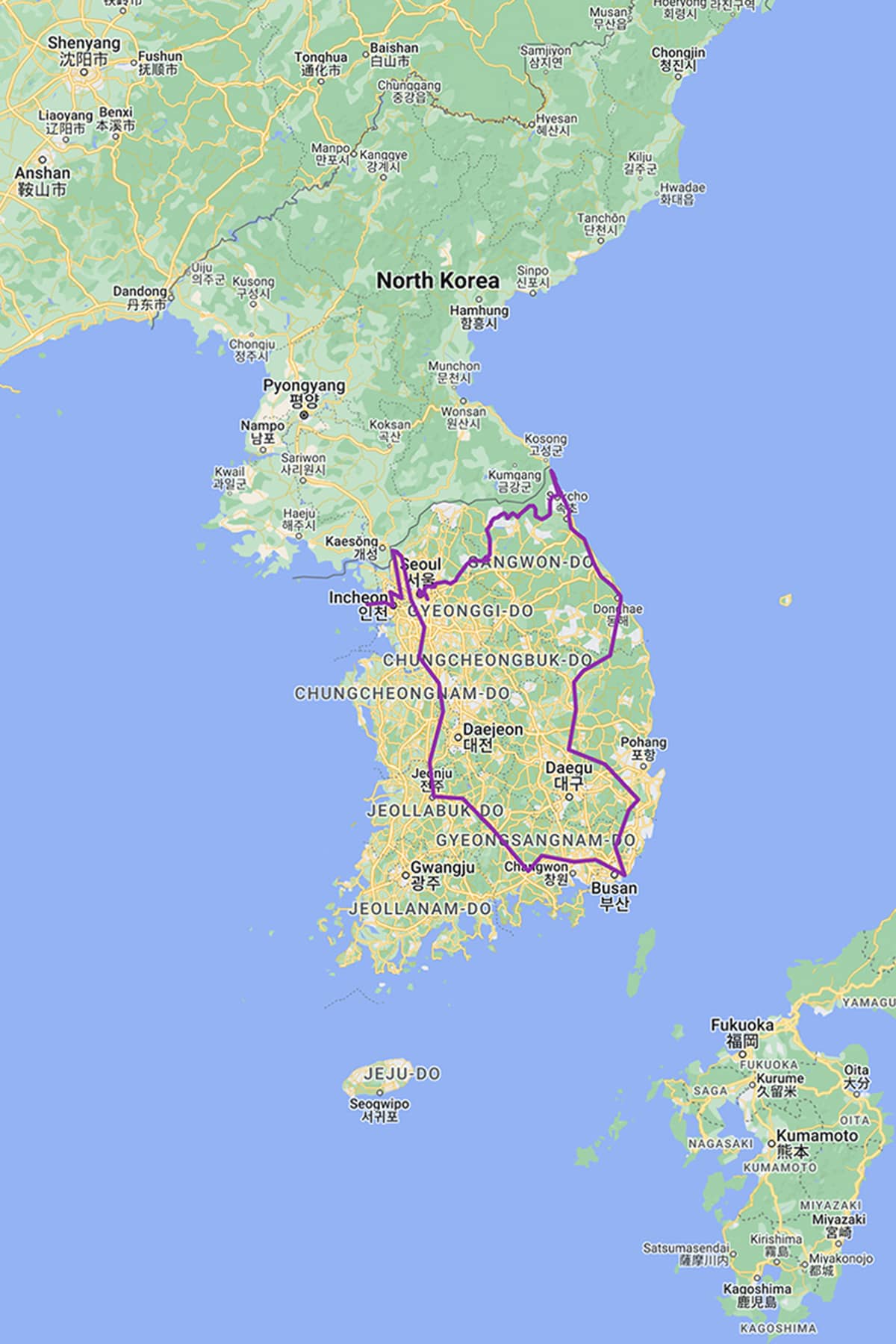

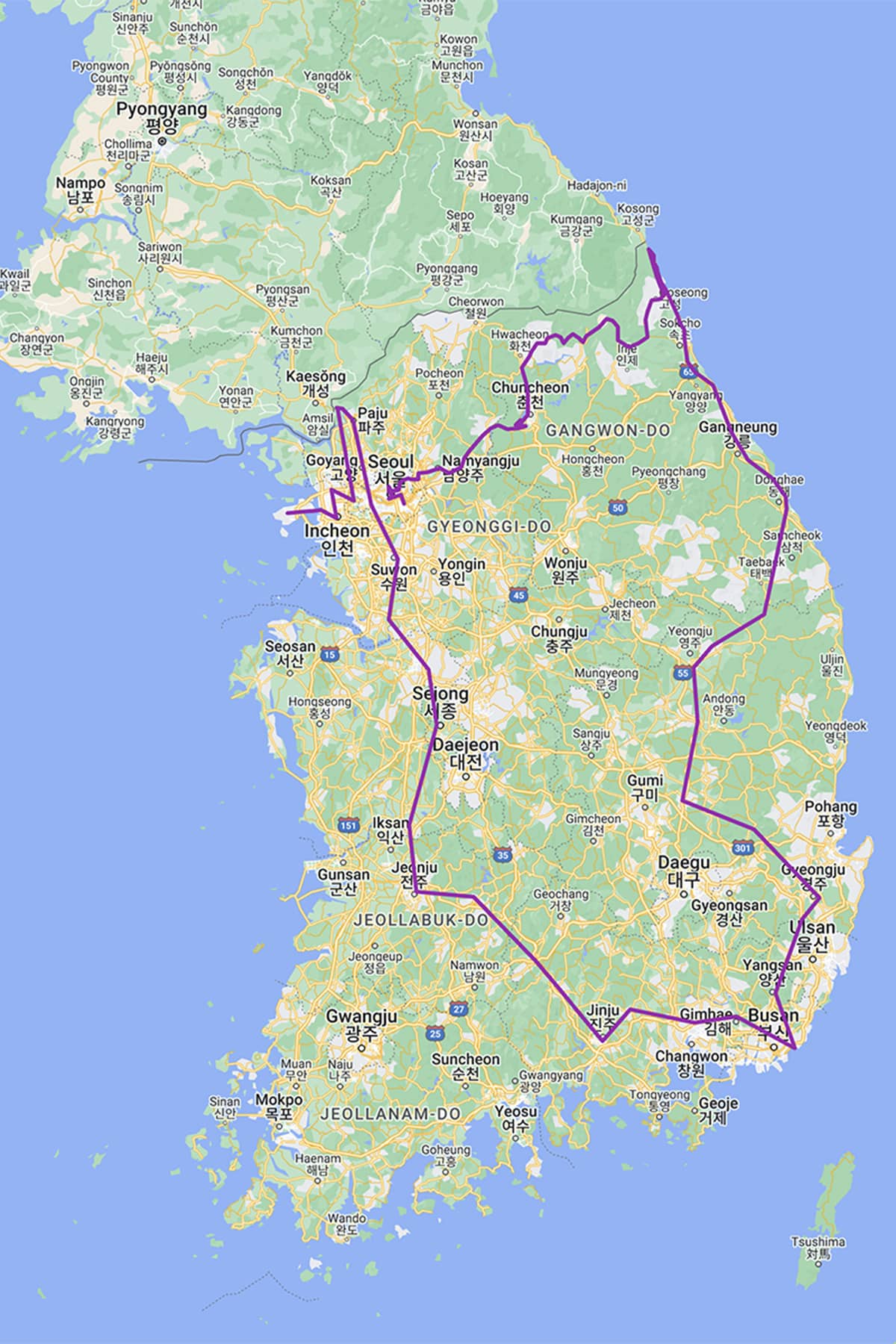

Half the time I was in South Korea in September I had the day-to-day stability of Seoul. For the second half of the assignment, we drove to a different city each day for almost two weeks. We traveled more than 800 miles around and across the entire South Korean peninsula, to Busan then up to the eastern coast. That gave me far more exposure to the Korea that existed beyond Seoul.

Other cities of note that we visited included Jeonju (전주시), Gyeongju (경주시), Bucheon (부천), Paju (파주시), Suwon (수원시), Sokcho (속초), Chuncheon (춘천), Busan (부산), Sejong City (세종시), Gimhae (김해), Samcheok (삼척), and Andong (안동), with sites in the counties of Goseong (고성), Yanggu (양구), and Hwacheon (화천).

What intrigued me was how so many of these cities were really large in their own right, with distinct histories. I did learn that the South Korean government had made efforts in recent years to support local tourist attractions. I saw the result of that work, and at times it was overwhelming as each city promoted why it was special. It was enjoyable to see for myself that civilization existed beyond Seoul, as it always had but with poor marketing for foreigners.

While some may criticize South Korea’s economic miracle as being based on the Chaebol or family business dynasties, it should be remembered that American wealth is absolutely derived from our long history of slavery. When comparing South Korea’s revenue from K-pop and tourism, both industries contribute significantly to the country’s economy, but they function in different capacities and scales.

K-pop, while a massive cultural export and revenue generator, operates within the entertainment sector, driving not only direct revenue but also boosting tourism through fan visits, merchandise sales, and international concerts. K-pop contributes $10 billion to South Korea’s economy annually.

Tourism remains broader, covering diverse sectors like hospitality, transportation, and attractions. It historically brings in more revenue overall, but K-pop’s influence is an increasingly vital part of the industry. Tourism was contributing $20 billion per year to the economy prior to COVID-19. It has gradually rebounded but not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Before leaving for South Korea, I made a personal effort to learn the Korean “alphabet” known as Hangul (한글). It was created in the 15th century by King Sejong the Great and his scholars during the Joseon Dynasty. Hangul consists of 14 consonants and 10 vowels, which are combined into syllable blocks to form words.

One of Hangul’s most distinctive features is its logical design. The shapes of the letters are based on the shape of the mouth and tongue when pronouncing the sounds. It is celebrated for being easy to learn, scientifically efficient, and highly phonetic, allowing for accurate representation of the Korean language’s sounds.

I fought learning Hangul for two decades, but I came by my stubbornness honestly. Having lived so long in either Japan or China, one culture or the other was always fighting for my attention. And while Korea did have a distinct and unique culture, it had been dominated in one way or another by both countries which left me confused at times about the best way to interact.

Even though Hangul was invented in the 1400s, Hanja – the traditional Chinese character, was still used by the government and academic institutions well into the 1900s. I could already read old Korean maps, because they used Mandarin characters. Or I knew Korean food by Japanese names. Just examples of how I was exposed to Korea but always through another culture’s language or interpretation of history.

After I learned to speak Japanese, just a year later I had to learn Mandarin. I was reluctant to take on the effort to learn Korean – even though many of my classmates were from Korea. We just spoke in the language we were studying, or English. Because Japanese Kanji are based on Mandarin characters, I could understand the meaning of words even if I did not know how to pronounce them. For Korean, Hangul was a whole other writing system and my brain refused to memorize yet another and self-contained alphabet.

But if I was going to spend time in Korea for this editorial assignment, I reasoned that I should try to learn some characters so I could recognize the meaning of signs at least. I knew I would never be able to learn the language, let alone pronounce many of the words correctly in a short time from self-study. But visual recognition of words was something I could have some success with.

I have tried language self-study courses of all kinds and never found them helpful. There was no way I could be immersed in a foreign language in Milwaukee. So I turned to Duolingo, a language learning app I used to refresh my Japanese before my assignment there earlier this year for the anniversary of Fukushima. It was not a well-structured study habit, but I had a lot of fun with the app and committed a couple hours a day to drills.

That was when I finally understood the absolute genius of the Korean alphabet. Within a month I had learned it. By the time I was in Korea, I actually had good basic recognition for signs and menus. I was even able to write Incheon from memory just by seeing the highway signs. Thankfully it is an easy name, and to be honest I got it 95% correct – forgetting to add a dot over part of the second character (인천). I continue with my daily Duolingo lessons because I still enjoy it, but I have most likely reached the limit of my linguistic ability.

Something I heard over and over both here in Milwaukee and there in Korea, from people who once lived overseas, was that they never felt they perfectly fit back into their homeland because their thinking had expanded due to their global experiences.

Everyone had something to say about the importance of identity, and their struggles to – different degrees – with what that meant. It was not a unique condition to Koreans or Korea, as I have talked about my own difficulties as an American coming back to America in previous essays.

If I were to overly simplify the way I understand Korean identity, it has more to do with “majority” thinking. Those who moved away for a while are in the minority. The Korean diaspora is widespread, with Korean communities established in over 180 countries around the world. The largest concentrations exist in China, the United States, Japan, Canada, Russia, Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Germany, and Kazakhstan.

Koreans have basically moved everywhere on the planet, all while managing to hold onto their cultural heritage. I think that is an incredible achievement, considering most Americans barely know what European country their grandparents immigrated from.

The Korean majority that never leaves Korea holds to a purist idea of what it means to be Korean, which I think can be a bit elitist. I am also not sure how authentic a lot of their standards are on what it means to be Korean.

I do not say any of this to pick a fight with Korean nationals. I say it because I see the same parallels here in my own country. When I traveled with George Banda to Washington DC in 2018 for the 35th anniversary of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, some random guy gave me a hard time for taking photos during the ceremony – even though I clearly wore a press badge and literally every veteran around me was using their iPhone to record the event.

He gave me a hard time about not being patriotic enough or showing enough respect. He was basically criticizing me for not being American enough. I pushed back hard, but quietly since I was standing right in front near the main stage. Who was he to judge me? He had no idea what I or my family had given this country.

My father was a decorated Vietnam veteran, and I grew up in the shadow of his war trauma. Even now, there are many political pundits to want to disqualify American citizens as true citizens for their faith, sexual orientation, political beliefs, or a series of other things that have no basis in constitutional law.

I search for the meaning of identity in America, just like I am sure everyone does in their life at some point – especially during those terribly awkward high school years. So I do tend to bristle over such judgments, most commonly when people use a self-designed standard of what it means to be a good Chrisitan as a club to blunt others.

One thought from an interview has stuck with me for many weeks, and I think it can apply to anyone. He said that most Korean Americans feel less than whole because they are not fully Korean and they are not fully American. Instead, how he found peace was to embrace that instead of being half, he was double.

He was fully Korean and fully American, and even if that made him something else that never quite fit it, he was fine with that because he was more and not less. He would not let others decide where he fit. I actually heard similar things from several people, and while it is not the only way to view the situation I think it is by far the healthiest one that I came across. It even brought a little more peace to my own condition.

So that is my hope for this series. For people to understand more about the Korean American situation in Milwaukee. But also for anyone to see our shared human conditions and gain some insight into their own life journey.

I think it takes an incredible amount of courage for anyone to share private parts of their life with the public. And even more courage to sit down with a stranger and immediately begin talking about the most traumatic times of their life.

I even tried for weeks to interview a North Korean defector but gave up on the idea after hitting insurmountable roadblocks. Then out of the blue – just a day before leaving Korea, I unexpectedly landed an interview. The opportunity to sit down and speak with a North Korean defector, for an American journalist, was something like catching a unicorn with a rainbow on the scale of impossibility. I did not learn anything new from the conversation, but I felt it put a face to a story and affirmed our shared humanity.

While there are some points of overlap in all the interviews in this special series, each voice speaks with its own authenticity. While one person may lack an experience, someone else has a story about it. I see this series as partly a puzzle to fit things together, and part dots that can be connected however it works best. Surprisingly, there were many more topics and many more people I could have included.

Otherwise, I have made the best and most honest effort as a journalist to be a translator and storyteller of all these life experiences, for people who happen to be Korean, or connected to Korea, or with ties to Milwaukee. I share the hope of many who I interviewed, that their stories will have a positive impact and help make a difference in the lives of others.

존경하는 마음으로

Lee Matz, October 2024

송리

Lee Matz

Lее Mаtz

Johnathan21 (via Shutterstock)

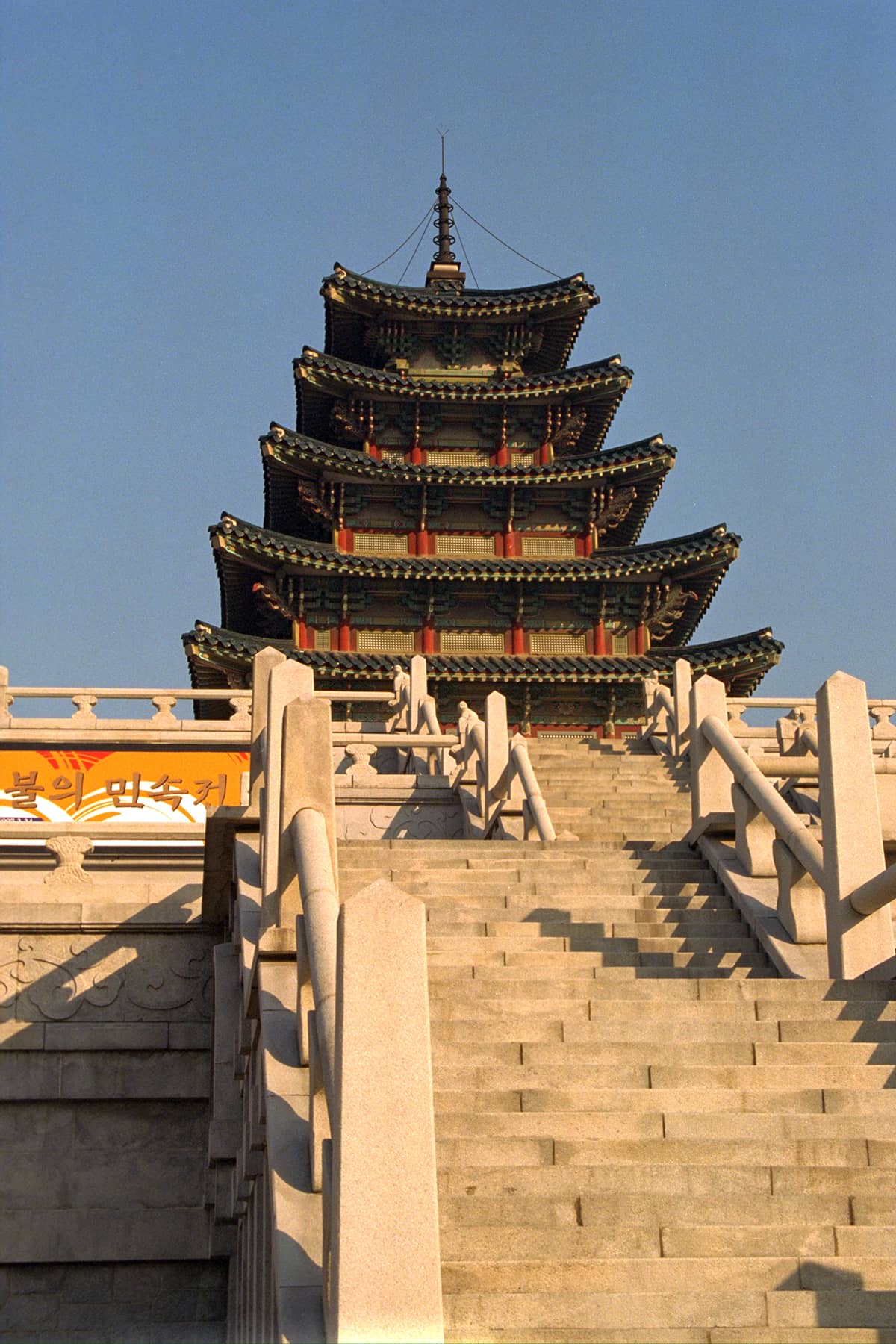

These never-before-seen images were taken in December 1996 by Lee Matz and published for the first time in this series for Milwaukee Independent.

Google Earth

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora