Steven Spielberg’s 1993 movie about a German businessman, who saved more than 1,200 lives during the Holocaust by hiring Jews to work in his factories, made Oskar Schindler a household name across America.

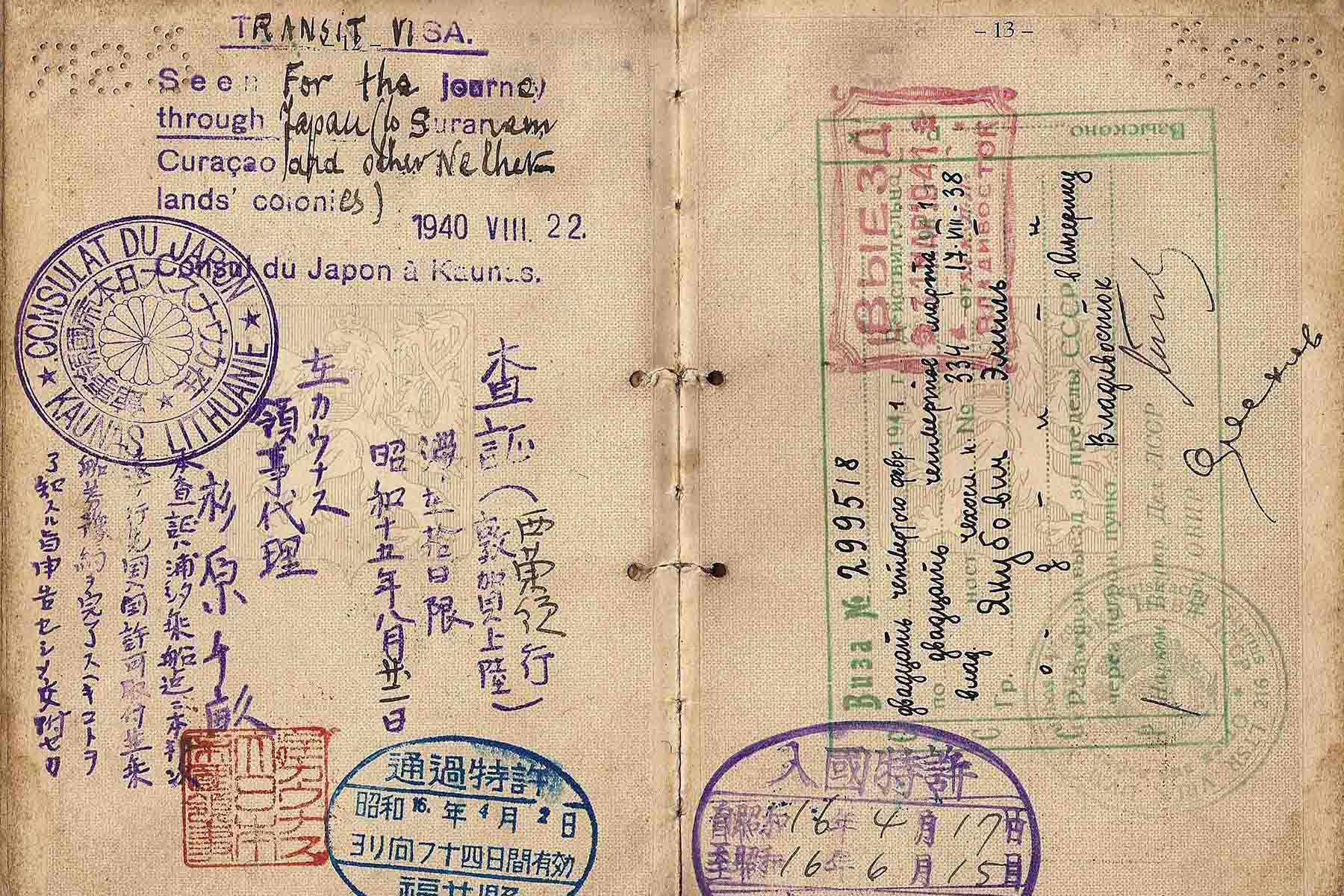

But Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who disobeyed his government’s orders and issued visas that allowed 6,000 Jews to escape from Nazi-occupied territories via Japan remains virtually unknown.

A partnership of Holocaust educators in Milwaukee wants to change that. A free staged reading of Chiune Sugihara: Unsung Hero of the Holocaust will be performed at the Nancy Kendall Theater in the Joan Steele Stein Center on the Cardinal Stritch University campus.

“What is so exceptional about Sugihara’s actions is that, as a man from a country and culture highly characterized by obedience and loyalty to the authorities, he had the courage to disobey his superiors,” said Dr. Shay Pilnik, Executive Director of the Nathan and Esther Pelz Holocaust Education Resource Center. “For Sugihara, the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” transcended all other obligations.”

The March 21 play is open to the public, and the program will be followed by the testimony of a Sugihara survivor, Chaya Small. The performance features Dwight Sora as Chiune Sugihara, and will be directed by Elayne LeTraunik, from the script written by Philip Pinkus.

The play looks at the life of Chiune Sugihara, also called Sempo Sugihara 杉原 千畝 Sugihara Chiune was a Japanese government official who served as vice consul for the Japanese Empire in Lithuania. During the Second World War, Sugihara helped around 6,000 Jews flee Europe by issuing transit visas to them so that they could travel through Japanese territory, risking his job and his family’s lives. The fleeing Jews were refugees from German-occupied Western Poland and Soviet-occupied Eastern Poland, as well as residents of Lithuania. In 1985, the State of Israel honored Sugihara as one of the Righteous Among the Nations חסידי אומות העולם for his actions. He is the only Japanese national to have been so honored.

Sugihara was asked 45 years after the Soviet invasion of Lithuania about his reasons for issuing visas to the Jews. He explained that the refugees were human beings, and that they simply needed help.

You want to know about my motivation, don’t you? Well. It is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them. Among the refugees were the elderly and women. They were so desperate that they went so far as to kiss my shoes, Yes, I actually witnessed such scenes with my own eyes. Also, I felt at that time, that the Japanese government did not have any uniform opinion in Tokyo. Some Japanese military leaders were just scared because of the pressure from the Nazis; while other officials in the Home Ministry were simply ambivalent.

People in Tokyo were not united. I felt it silly to deal with them. So, I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain about me in the future. But, I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people’s lives. The spirit of humanity, philanthropy, neighborly friendship, with this spirit, I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation—and because of this reason, I went ahead with redoubled courage.

The following year, Sugihara died at a hospital in Kamakura, Japan on 31 July 1986. In spite of the publicity given him in Israel and other nations, he remained virtually unknown in his home country. Only when a large Jewish delegation from around the world, including the Israeli ambassador to Japan, showed up at his funeral, did his neighbors find out what he had done. He may have lost his diplomatic career but he received much posthumous acclaim.

The Backstory

Sugihara was raised in Gifu Prefecture under the strict Japanese code of ethics in the legacy of a middle-class rural samurai family. He learned the virtues of the Japanese society that included love for the family, for the sake of the children, duty and responsibility, or obligation to repay a debt, and not to bring shame on the family. Internal strength and resourcefulness and withholding of emotions on the surface, were other virtues Sugihara learned and displayed in his attempted to rescue the Jews.

In 1939, Sugihara became a vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania. His duties included reporting on Soviet and German troop movements, and to find out if Germany planned an attack on the Soviets and to report the details of such an attack to his superiors in Berlin and Tokyo.

The German invasion of Poland filled Lithuania with Jewish refugees who were escaping from Hitler’s advancing troops. In order for the fugitives to escape, they needed transit visas. Without these visas it was dangerous to travel, and it was impossible to find countries willing to issue them.

On a summer morning in late July, 1940, consul Sugihara awakened to a crowd of Jewish refugees gathered outside the consulate. The refugees knew that their only path lay to the east and if Sugihara would grant them Japanese transit visas, they could obtain exit visas and race to possible freedom.

Sugihara needed permission from the Japanese Foreign Ministry otherwise, he had no authority to issue out hundreds of visas. But permission was denied three times by the Japanese government. Sugihara was faced with a difficult decision. He had to make a choice that would probably result in extreme financial hardship for his family in the future. He also knew that if he went against the orders of his government, he might be fired and disgraced, and never work for the Japanese government again.

Sugihara made a decision based on the hundreds of desperate Jews lined up outside the consulate. He disobeyed the Japanese government and forged documents to help the refugees to safety. Sugihara and his wife wrote over three hundred visas a day, which would normally be done in one month by the consul. He did not even stop to eat because he chose not to lose a minute. People were standing in line in front of his consulate day and night for these visas. After getting their visas, the refugees lost no time in getting on trains that took them to Moscow, and then by trans-Siberian railroad to Vladivostok. They had escaped the death camps and the Holocaust all together.

In 1945, the Japanese government informally dismissed Chiune Sugihara from the diplomatic service and his career was shattered. Then Sugihara and his family were forced to leave Lithuania and go to Romania. In Romania, as punishment for his actions, he was imprisoned for two years. When he returned to Japan, he was in disgrace. He worked at odd jobs to support his family.

The Aftermath

Sugihara never spoke about his dismissal because it was too painful for him. He also never spoke about his deeds. Donald Gartman, director of the United Jewish Federation of Utah, said Sugihara obeyed his conscience about what he thought was the right thing to do and not the directives of his country. He had the power to produce effects of his efforts. For example, even as he was on the train that was pulling away form Lithuania on his way to Romania, he was still signing papers as fast as he could and throwing them out of the window.

Heroes who resisted Nazi cruelty were under lots of pressure on what decisions they should take to save Jews. If they were caught they would probably face imprisonment, execution, or sent to the death camps. Chiune Sugihara showed how he did not fear any of these punishments. All he wanted was to rescue desperate Jews who asked for his help.

“Most people have this idea that you can’t really help the whole world, so what’s the point?” said Mark Salomon, one of the estimated 40,000 descendants of Sugihara survivors. But Sugihara showed that “whatever you are doing with yourself, you are having a much broader impact. Sometimes it’s hard to see the forest through the trees, but it’s important in every aspect of your life to remember you are having an effect and to make it a positive effect.”

The program and performance at Cardinal Stritch University of Chiune Sugihara: Unsung Hero of the Holocaust is made possible through the generosity of the Widell Lecture Series Fund of the Jewish Home and Care Center Foundation.