Rick Wood had the rare opportunity to travel from Milwaukee to North Korea in 1995 to take photos as part of a humanitarian mission. At that time it was estimated that only about 200 U.S. citizens had been granted access to the reclusive country in nearly 50 years.

For Wood, the journey was more than just taking pictures. He saw it as an opportunity to connect with the people of North Korea, even if under the watchful eyes of the authoritarian government.

“I had established a lot of connections within the Milwaukee church I was attending. One day, a speaker named Jim Groen came to talk about the humanitarian work they were doing, including a project in North Korea. It inspired me to volunteer,” said Wood. “So after the talk, I approached him and mentioned that if they ever planned another trip there, I’d be interested in joining.”

Although it was a Christian organization, the Denver-based Worldwide Leadership Council did not promote religion or any faith-based doctrines with their projects. The focus was on building friendships and relationships in third-world countries.

After Groen looked over Wood’s extensive portfolio, he realized how important it would be to have a personal photographer document the experience. The organization had a trip planned for April 1995 and Groen wanted Wood to accompany him.

“Our plane was an old Soviet Ilyushin aircraft with bald tires. We flew from Beijing in the evening and as we approached North Korea, the lights below us just went out, it was completely black,” said Wood. “After we landed, all of a sudden I became the center of attention. The North Koreans were all photographing me instead of the other way around.”

As a photojournalist, Wood was used to being behind the scenes to tell stories, so it was an adjustment to be thrust into the spotlight. Most North Koreans had never seen a foreigner before, let alone a photojournalist.

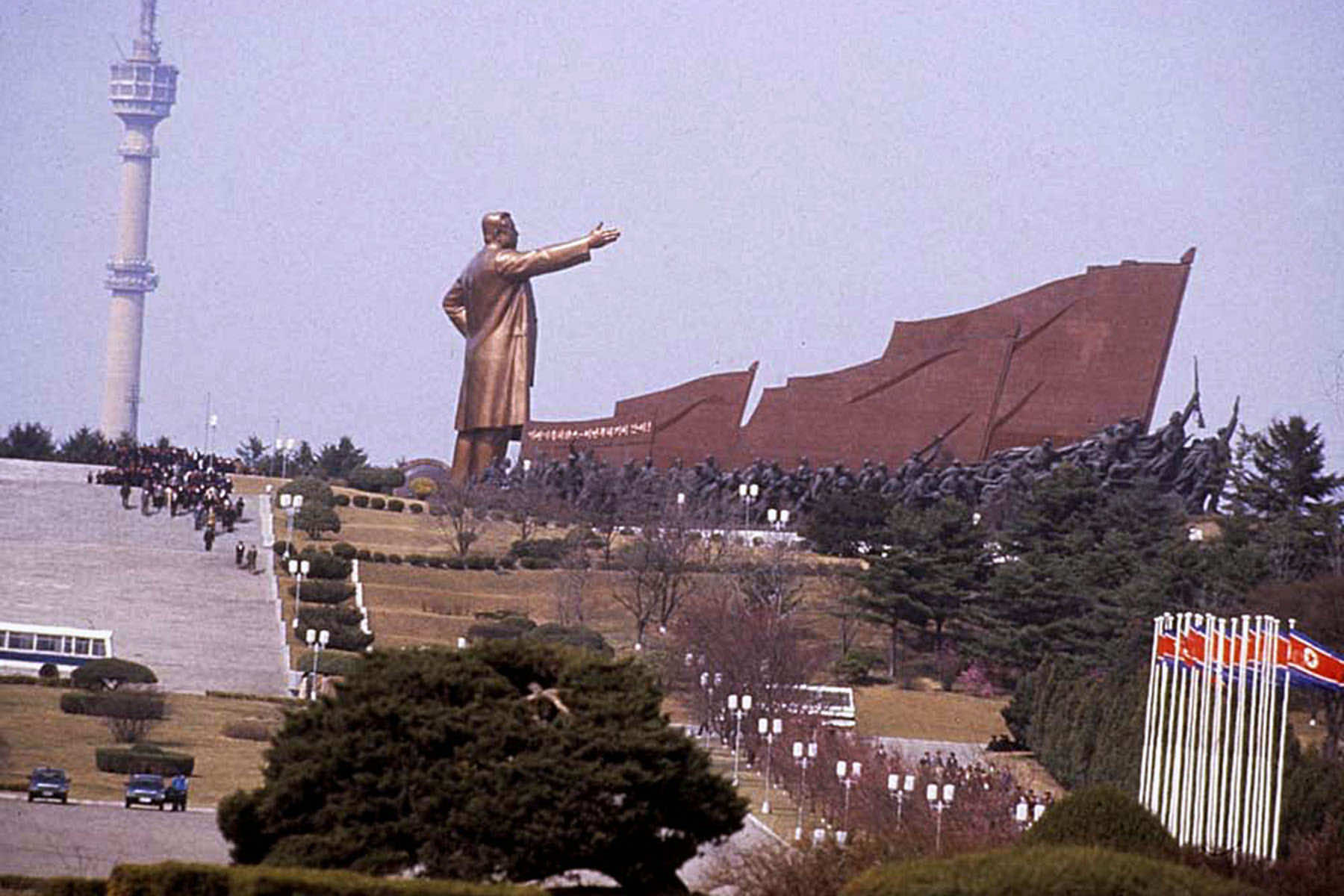

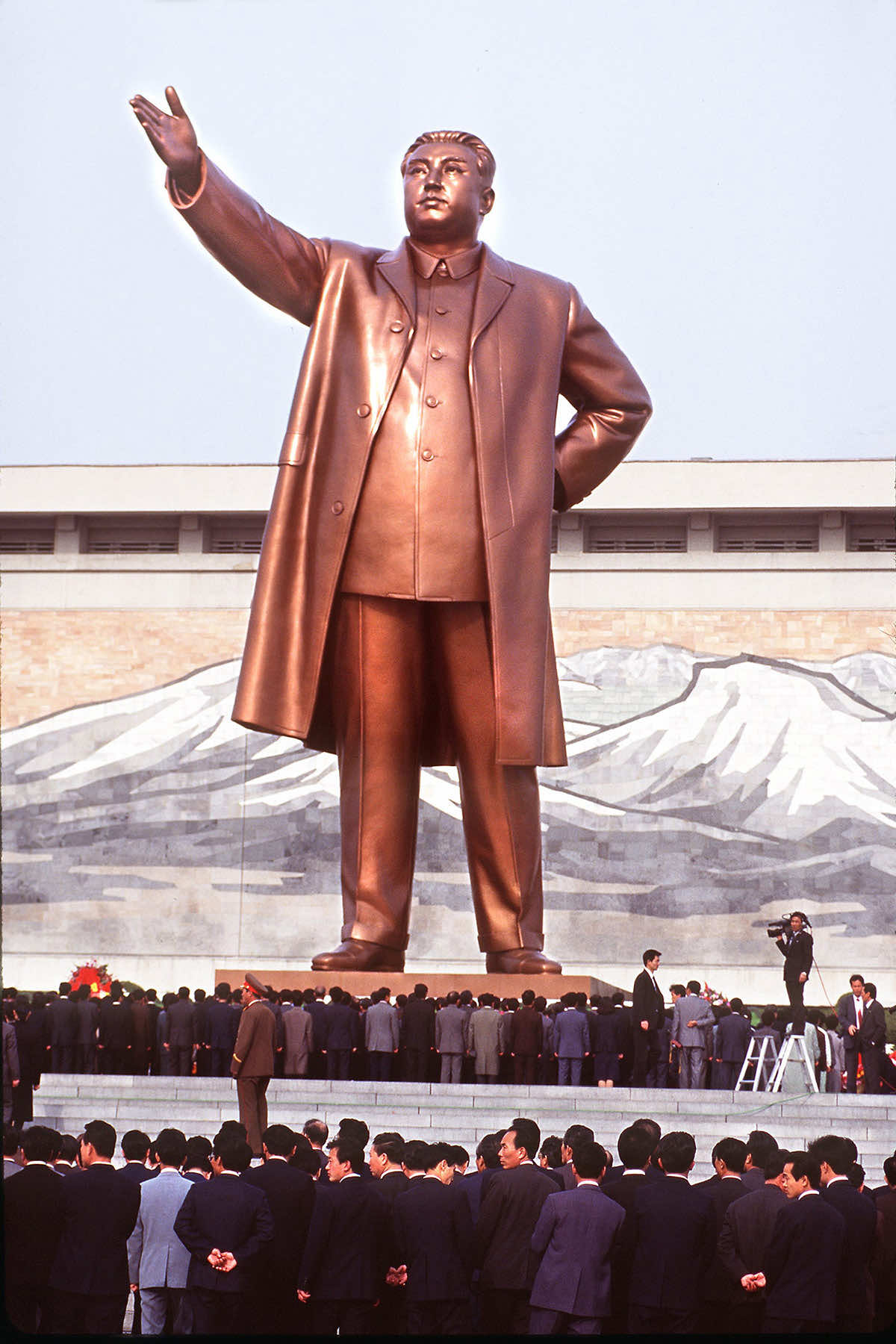

His group was taken to see the famous statue of Kim Il Sung, and that night the State news reported, “After 30 years, Americans finally come to North Korea to honor Kim Il Sung.” Wood had been prepared to experience that kind of propaganda, but he still found it shocking.

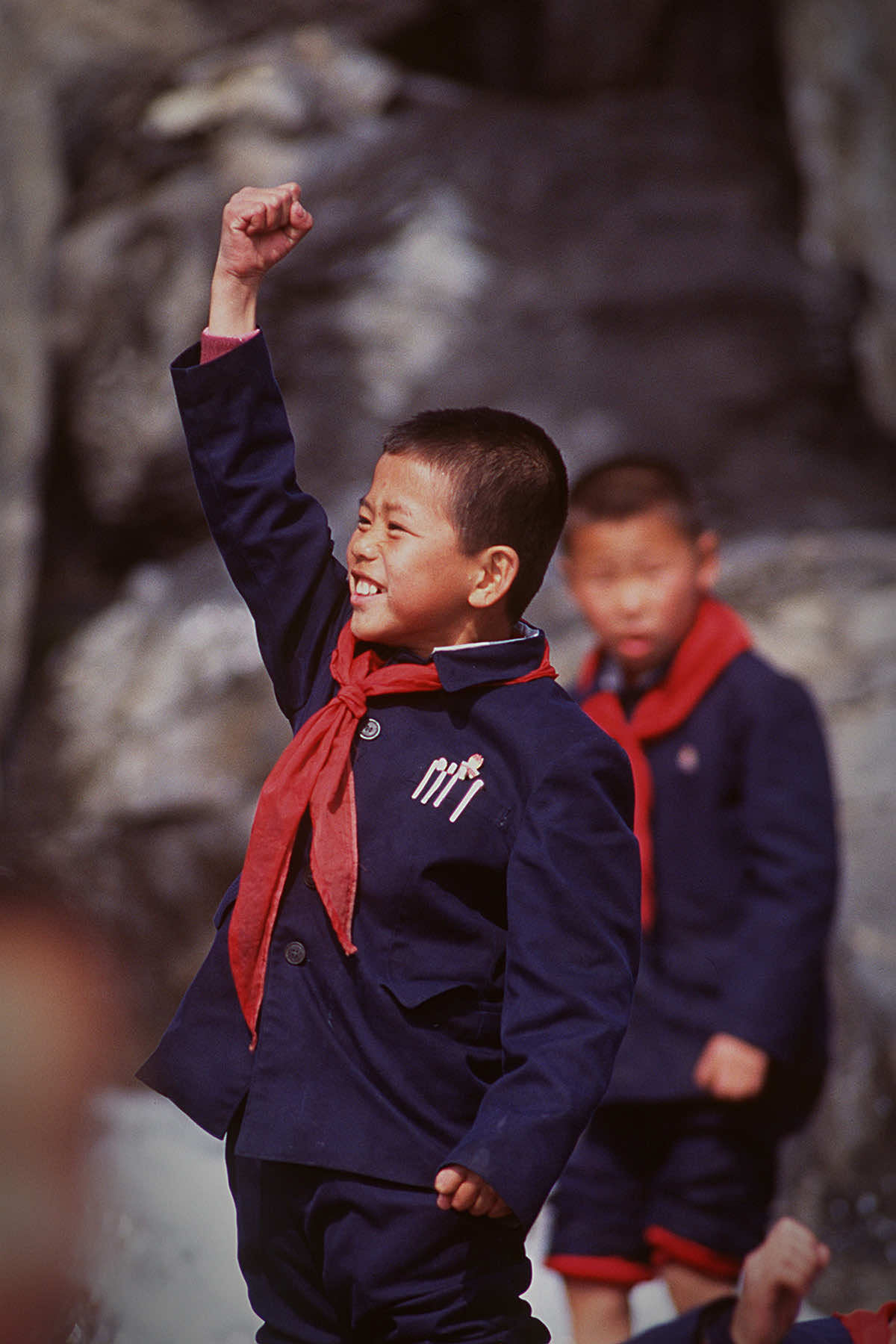

“We heard people back in the United States saying we were being naive, that we were being used as tools of propaganda. I acknowledged that perspective but insisted that it’s important not to overlook the human connections we were making, even if only for a few moments,” said Wood. “Those interactions — the handshakes, the exchanges of gifts, the eye contact, the faces of curious children hoping for a better future — weren’t just propaganda. They represented a genuine desire for a human connection.”

Wherever Wood has traveled, his approach was always to build rapport with the people he met on the streets of those countries. North Korea was no different, but he was very aware of the scrutiny he was under. North Korea had become the most closed society in the world after the war. Very few foreigners were permitted entry, and foreign radio broadcasts were completely jammed.

“My belongings were searched and even taken apart, and that’s just part of the process. It’s one thing to hear about it, but experiencing it firsthand is a different story,” said Wood. “However, I was honestly and genuinely there to build connections, so while it was an inconvenience I wasn’t really concerned.”

Wood said he became very intentional about reviewing the itinerary and planning where the group would be so he did not overshoot. In uncomfortable situations, it would be easy to fall into the trap of taking too many photos. He also thought it would be disrespectful to be “machine gunning” pictures in rapid succession.

In 1995, digital cameras were still in their infancy and could not compete against the quality of 35mm film. Which meant that Wood had a limited number of pictures he could take at 24 frames per roll, even though he brought many extra rolls.

“I wanted to be more deliberate, capturing the right moments as they happened rather than just clicking the shutter continuously. It takes discipline not to press the button simply because you can. Anyone can take thousands of photos, but that doesn’t guarantee capturing the best ones,” said Wood. “So I focused on being patient and observing what was happening around me, and I looked for the best moments. My aim was to get close to the North Korean people, to listen to their stories, and to share some of my own. I wanted to connect on a personal level, talking about common experiences like our children going to school. I made it a point to ask a lot of questions, show genuine empathy, learn about what they do, and understand what they are passionate about.”

The approach allowed Wood to build trust, but not enough to feel comfortable to venture outside the areas the group was allowed to visit. What he was able to capture on film was deeply meaningful and unprecedented, and his arrival in Pyongyang came at a tragically historic time for North Koreans.

Kim Il Sung, the founding leader of North Korea, died on July 8, 1994. He passed away from a heart attack at the age of 82. Kim had been the leader of North Korea since its establishment in 1948 and was succeeded by his son, Kim Jong Il. His death marked a significant moment in North Korean history, and the country observed a period of national mourning.

“I was there for the April 15 festival they held in honor of Kim Il Sung, almost a year after his death. It was the annual birthday celebration of Kim, and the first time that North Koreans marked the day without their ‘dear leader.’ I saw people weeping, genuinely grieving, and my first thought was if they were just putting on a show for the cameras,” said Wood. “But then I had to reconsider. I realized that, regardless of how we might perceive it, their emotions were real to them. Rather than passing judgment on whether their feelings were genuine or not, I recognized that it was important to meet them where they were, just as they were meeting me where I was.”

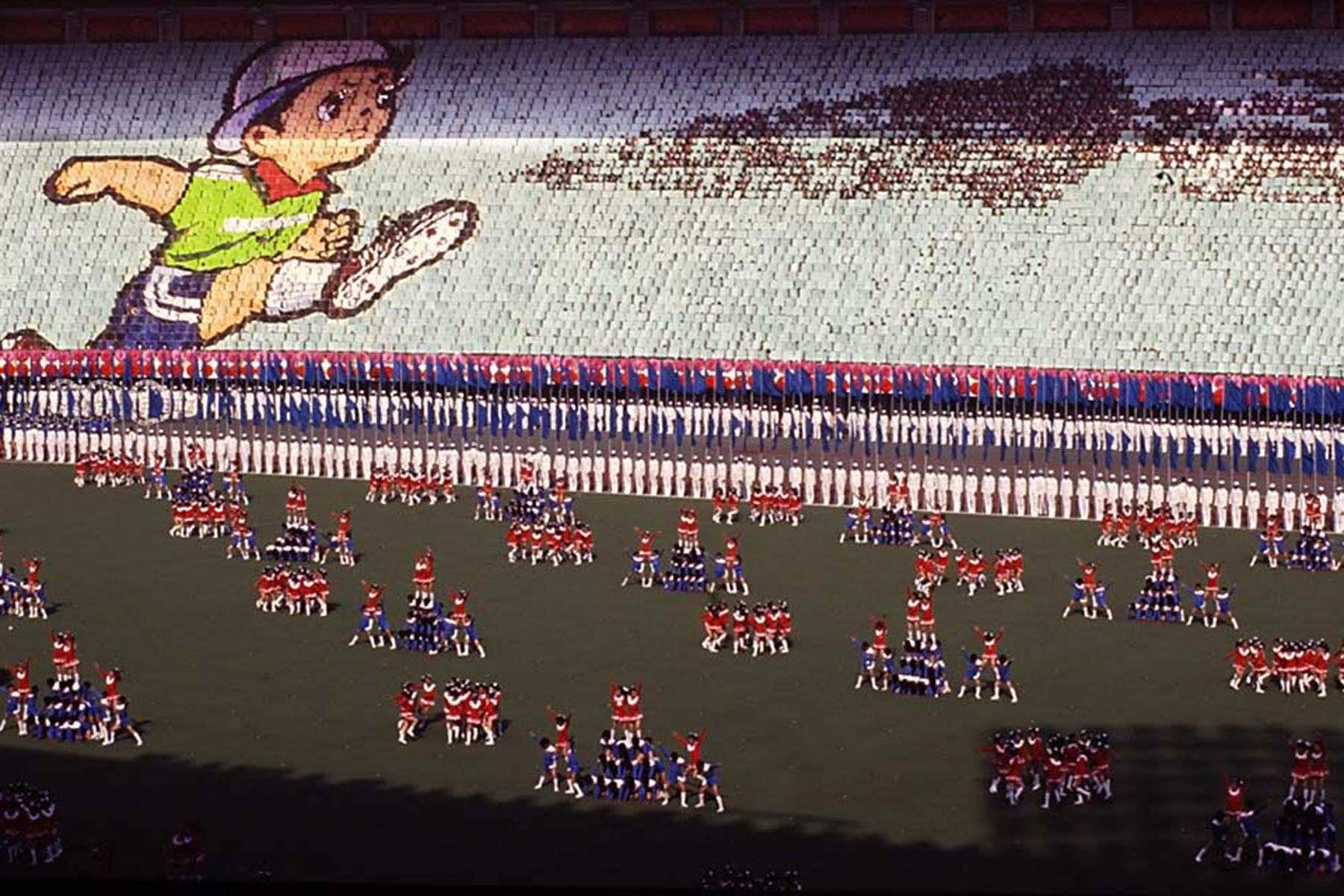

Wood joined an estimated 50,000 spectators for an hour-long “Mass Display of Appreciation for Kim Il Sung.” The stadium crowd formed elaborate murals by holding up books of colored paper, their presentation accompanied by music.

“Each cue happened precisely, and when the colors shifted a new scene was revealed. There were several compositions, starting with a compassionate Kim Il Sung standing in a wheat field. Other murals followed displaying patriotic scenes,” said Wood. “On the field there were groups of young children who displayed their gymnastics talents. After each performance, I could see they were visibly emotional and crying as they left. Their grief was echoed by parents in the stands beside us, who also broke down in tears.”

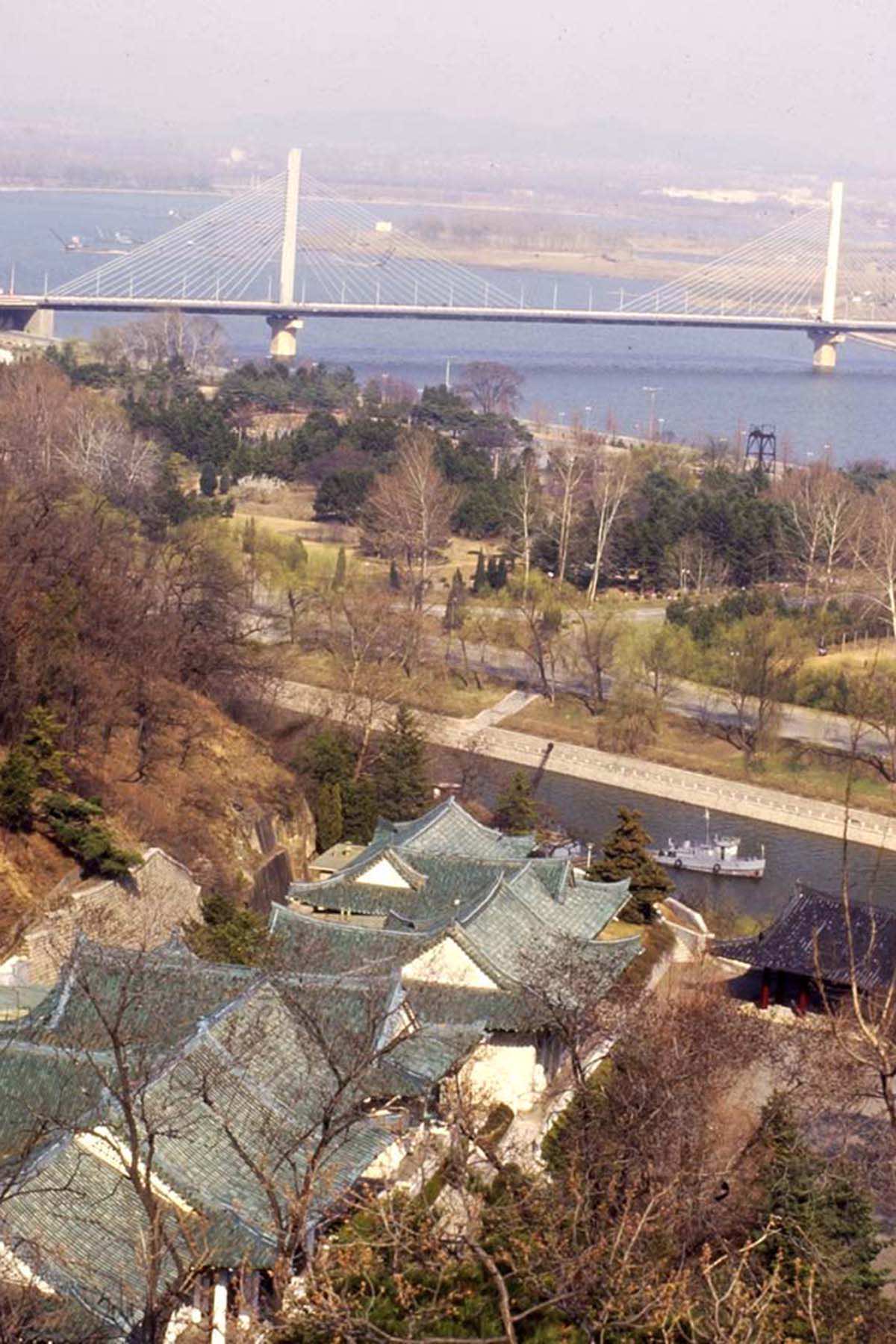

At one point in their trip, Wood and Groen were taken for a drive on the Reunification Highway, also known as the Pyongyang-Kaesong Motorway. It had opened just three years earlier in 1992, as a project initiated by Kim Il Sung after reunification talks with South Korea. The highway connected the capital city of Pyongyang with the city of Kaesong, near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that separated North and South Korea. Wood remembered Groen telling their hosts that he looked forward to the day when North Koreans, South Koreans, and Americans could walk across the DMZ by way of the highway.

“The real value of the trip, for me, was the opportunity to interact with the local people. Even though everything was tightly controlled, it was a chance to let them see an unfiltered American and to try to have genuine conversations about their lives,” said Wood. “It was striking how terrified people were of us on the street. We had these little friendship pins with the American and North Korean flags that we tried to hand out, but people wouldn’t come near us. They were afraid because accepting a pin could lead to being stopped and questioned by authorities. It was clear how structured and controlled their society was, but within that, even a small gesture like a smile or a handshake could mean a lot.”

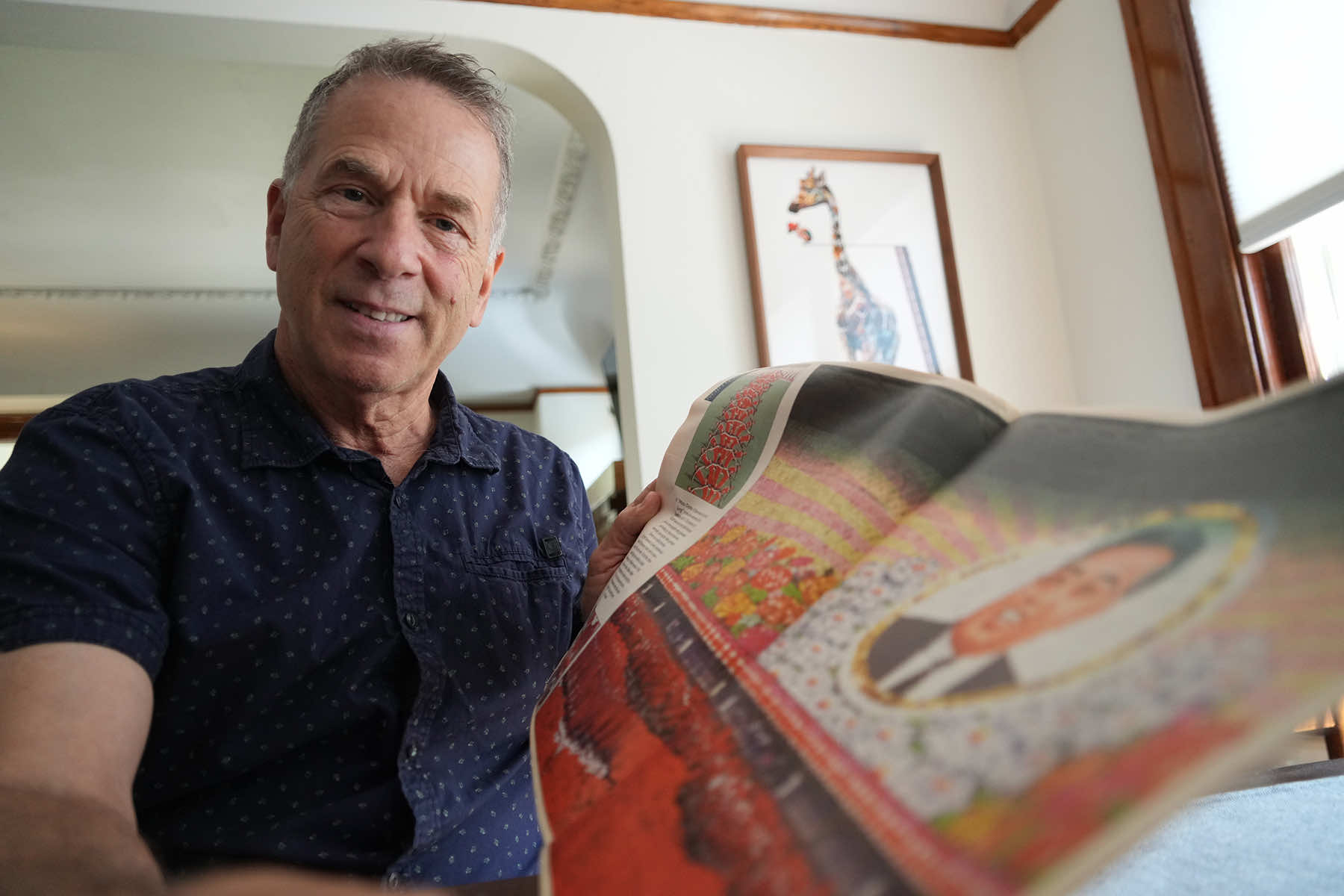

Those were the intimate moments that Wood endeavored to record on film. For more than 40 years, from 1978 to 2020, images taken by Wood could be found almost daily in the pages of the local newspaper now known as the “Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.”

“Every night, I would take notes and write in my journal, filling pages with my observations, the names of places, and people I met. By the end of the trip, I had maybe four or five notebooks full of notes,” said Wood. “What really helped me process everything was taking the time afterward to decompress and reflect on what I had seen. Sorting through the photos also played a crucial role, as the images often helped to shape the story.”

While Wood worked for a newspaper, the editors did not send him on the assignment to North Korea. His primary goal for going was to document the trip for Groen’s organization and to participate for his own personal fulfillment. The notion of journalism was secondary.

So it was not a foregone conclusion that his photos or story would be published. But upon his return to Milwaukee, Wood decided to pitch the newspaper’s editors on the idea of sharing his experience with the public.

He was fortunate to work with some excellent editors who helped him construct the narrative of the story. But before that loomed a larger question, “Why should a Milwaukee-based newspaper care about what was happening in North Korea?”

“My response was that the ‘Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’ was a major national paper that takes pride in telling important national stories. We had a budget, a history, and a tradition of covering significant events, and this was my effort to honor that tradition,” said Wood. “The editors I worked with were committed to upholding that standard and they, along with some great writers, helped me craft the story, ask the right questions, and delve into the details. Their support was invaluable to me.”

The “Milwaukee Journal Sentinel” was created through the merger of two newspapers, the “Milwaukee Journal” and the “Milwaukee Sentinel.” The merger took place on April 2, 1995, just days before Woods left for North Korea. His essay and photos were published on June 25.

Over the course of his four decades as a photojournalist, Wood captured moments that defined history, culture, and humanity. From a small neighborhood in Terre Haute, Indiana where he grew up, to the Twin Towers in New York on 9/11, Wood’s journey was marked by a relentless curiosity, a deep sense of compassion, and a commitment to telling stories that matter.

“I took a high school class in photography and just fell in love with it immediately. The idea of putting a piece of paper in the developer liquid and seeing the image come up, it was like mesmerizing,” said Wood. “I found that working for the school newspaper and the yearbook gave me access to all sorts of things. People wanted to be in the paper. They wanted to be in the yearbook. And I enjoyed being that conduit for taking those pictures to tell stories.”

His experiences, both personal and professional, shaped his approach to photography and journalism, making him a respected figure in the field beyond Milwaukee. Wood not only documented the world but also deepened the public’s understanding of it, one frame at a time.

“When I hear news about North Korea or other places I’ve been, I don’t just see it as a headline. I think about the people I met there, the relationships I built,” added Wood. “It’s easy to get caught up in the politics, but at the end of the day, it’s the human connection that matters. We can agree to disagree, but we have to respect each other as people. That’s what I’ve tried to do in my work — capture those connections, those moments of understanding, and share them with the world.”

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora