History and national pride are often intertwined with everyday life in South Korea. One particular story that has captured the attention of many, who live in the capital city of Seoul, involves the legend of iron rods that were driven into the earth by Imperial Japan during their 35 years of colonial rule.

“Pung su (풍수),” the Korean term for “feng shui (风水),” is the ancient Chinese geomancy practice that studies the flow of the earth’s energy. In South Korea it is believed that this energy flows from Mount Baekdu through the Baekdu-Daegan mountain range, forming the country’s central nervous system for spiritual strength. The flow of energy is thought to fill South Korea with its national spirit.

During Japan’s occupation from 1910 to 1945, it was said that Imperial soldiers drove iron rods into the sacred mountains at key points to weaken Korea’s pung su. It was an effort to break the will and resistance of the Korean people, and an effective propaganda tool.

While unsupported by hard proof, the belief that the Japanese stakes existed and their power was disruptive has been deeply ingrained in the Korean national psyche for decades. Stories about the stakes have been passed down through generations, and they are often cited as a cause of the nation’s unease and difficulties.

The belief has also been reinforced by anecdotal evidence and oral testimonies from older residents who claim to have witnessed or heard about the stakes being planted. After World War II, when Korea regained independence, the provisional government sought to find and remove the stakes. Geographers and shamanists were dispatched across the countryside.

However, Japanese officials in custody did not acknowledge the stakes or disclose their locations, fueling a sense of unease and unfinished business in Korea. It was believed that Japan remained keen to dominate Korea economically rather than militarily in the post-war world.

Many South Koreans continue to feel the lingering wounds from the Japanese occupation, a period marked by cultural suppression and attempts to erase Korean identity. Removing the stakes was seen as a way to restore the nation’s spiritual and cultural harmony.

The task of removing the stakes was further complicated by Korea’s heavily forested and mountainous terrain, making aerial or satellite detection impossible. Even technological advancements have proven ineffective. South Korea’s first domestically built geomancy satellite, intended to detect feng shui anomalies from orbit, was destroyed in a mid-air explosion shortly after launch, further hindering the search efforts.

Despite these challenges, the quest to find and remove the stakes has persisted, driven by both scientific curiosity and nationalistic fervor. Elderly South Koreans, particularly those who grew up hearing the stories, have searched for years to locate the Japanese stakes.

As each year passes the number of dedicated searchers dwindles. But for a time it was common to see individuals spend their weekends climbing mountains and valleys, looking for metal posts, nails, and rods that they believed were remnants of the Japanese colonization.

Despite the passionate search, concrete evidence remains lacking. There are no documented records from the Japanese military or colonial authorities about planting these stakes. Skeptics argue that the stakes could have been used for other purposes, such as anchoring cables during the Korean War or for geological surveys.

The stakes that have been found vary in design, material, and size, complicating the narrative of a coordinated effort by the Japanese.

One such story involved a former Japanese general, Tomoyuki Yamashita, who allegedly confessed to a Korean translator during World War II that the Japanese had planted metal poles throughout Korea to disrupt the people’s spiritual energy. While compelling, the story lacked concrete evidence, leaving the search for definitive proof ongoing.

Adding to the complexity is the role of Korean shamans, who historically used metal objects in their rituals. In the mid-1990s, the buzz about Japanese metal posts was fueled by the government’s move to reexamine the country’s colonial history. However, discoveries of metal posts and knives in the tomb of Admiral Yi Sun-shin, a revered war hero, revealed that many objects were likely planted by shamans for ritualistic purposes.

Many historians now believe that the mysterious metal posts found in South Korea were predominantly used in shamanistic practices. Despite that, the legend of the Japanese stakes persists, driven by historical grievances and a desire to reclaim Korea’s spiritual harmony.

The recovery work involves a mix of meticulous research and hands-on exploration. It begins by gathering reports from hikers, park authorities, and local residents who have encountered suspicious metal objects. Once a potential site has been identified, researchers travel into the mountains, equipped with tools to excavate the stakes. Each discovery is documented, and the objects are often turned over to local authorities or preserved as historical artifacts.

Such efforts are part of a broader movement within South Korea to address and heal the wounds of the past. Civic groups and historians support the searches, viewing them as an important step in reclaiming Korean history and identity. The movement has gained traction over the years, with more people becoming aware of the stakes and their symbolic significance.

But while many Koreans support the search for the Japanese stakes, believing it is essential to reclaiming their national spirit, there are also controversies and debates surrounding the issue. Some argue that the focus on hunting for the stakes distracts from more pressing contemporary problems. Others question the historical accuracy of the claims, pointing to the lack of concrete evidence and the role of shamans in planting metal objects for ritualistic purposes.

Despite the opposing debates, the recovery movement has a significant following. Public ceremonies are sometimes held when stakes are discovered and removed, symbolizing the cleansing of the land and the restoration of Korea’s spiritual harmony. The events are often covered by local media, further fueling interest and support for the cause.

Looking to the future as the years pass, the search for Japan’s stakes faces new challenges. Changing demographics and modern lifestyles mean fewer young people are interested in joining the hunt. The urgency that once drove older generations to the mountains continues to wane, raising concerns that Korea’s national spirit might never be fully restored.

Then there are those individuals who share the belief in the cause, and feel the quest is far from over. Each discovery of a rusted hoop or nail unearthed from the ground is a step toward healing and reclaiming Korea’s spiritual heritage. Whether or not the stakes were truly planted by the Japanese, the search itself has become a powerful symbol for the restoration of South Korea’s national spirit.

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

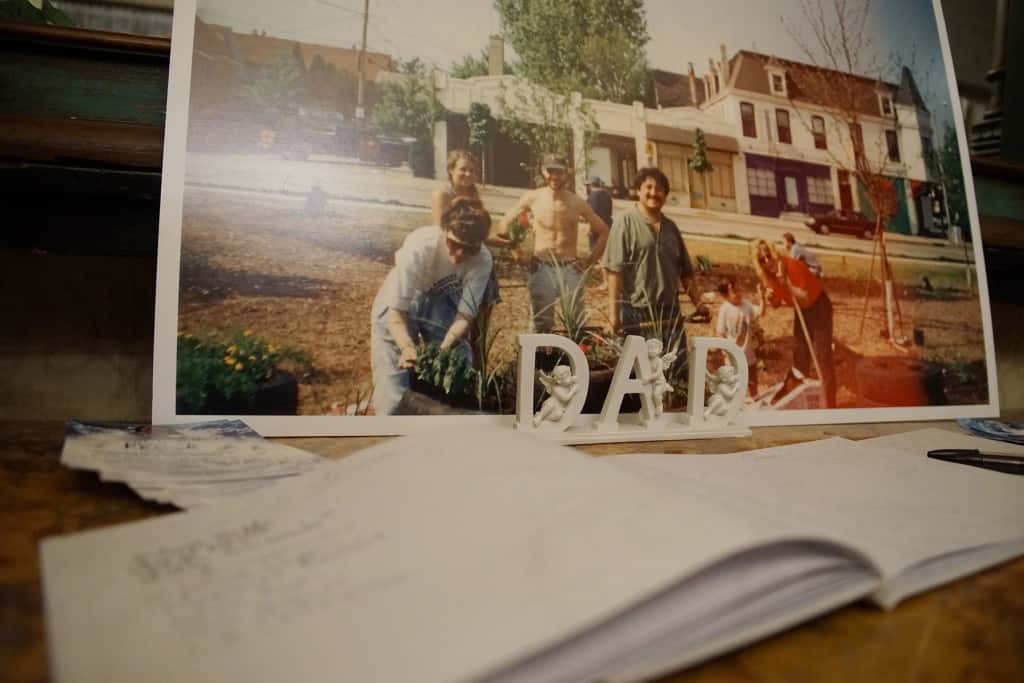

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora