At any single point in human history, there are only a handful of people who can turn a tree into a chair, a cabinet, a floor, or who can turn a lump of iron into a chisel, a lock, or a fork. Patrick Burke is one such person, a world-renowned artisan who produces stunning work from his rural workshop in Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

Our daily lives are filled with objects which we rely on even though we hardly understand how they function or how they are made. While many take it for granted that somewhere this knowledge is always preserved, the reality is that all of the accumulated knowledge which is still with us was passed down tenuously and sometimes miraculously through the millennia.

Those who take the transaction of this knowledge between generations for granted should think of the thousand-year void in Western science and the arts, a period we now call the Middle Ages. The tradition of skill that created the life-like sculptures and monumental architecture of the ancient Greeks was simply forgotten.

Much of humanity returned to the technical level of civilizations that long predated Greco-Roman culture and many of the painted works that survive from the Middle Ages resemble those that the children of the ancients were capable of creating.

Only in the 15th century did the Western world remember its heritage. It resumed where it had left off after a long fog, and ushered in the time we know as the Renaissance. Five hundred years later, the same arts are still with us thanks to the few who have passed them down through the generations, and the even fewer who practice them now.

In the United States, the only man I can think of who can sculpt wood like the ancients, can himself only think of one other person whom he can ask for help with especially demanding projects.

Patrick Burke, a true Renaissance Man, is a classically European-trained sculptor, wood carver, designer, and furniture maker.

Walk into his shop Manitowoc, Wisconsin and you will see a mold and clay study of a head for a public bronze sculpture, next to it an award medallion for the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, resting by mahogany table legs with beautifully carved ornamental designs for private clients and museums.

This is merely what sits on the bench; the walls are adorned with demonstrations of various carving techniques, wooden sculptures of hands, and busts, all covered in many hours of sawdust.

The purpose of my recent visit to his inner sanctum was for an upcoming short documentary focusing on Burke and his work. As a filmmaker, I am interested in people with exceptional skills and, even more importantly, the mindset that they must have adopted to acquire those skills.

In Patrick’s case, his work speaks for itself and I believe that it will both justify, as well as spread to you, my fascination for it.

One of his recent projects included recreating a missing 16-foot dining room table, from only two remaining black and white photographs, for the Glessner Museum in Chicago. One of the chairs from the original set, which is still in the museum’s collection, offered Patrick some additional guidance when it came to reverse engineering the dimensions of the table.

Calculating the distance between the armrest of the chair and the edge of the table, and accounting for how much the table would sink into the carpet due to its weight, Burke was able to glean the dimensions that the table needed to have.

By first creating a mock table with those dimensions and photographing it from the exact angle that the two historic photographs showed, he was able to further confirm his measurements. He even recreated the original metal hardware of the table, before aging them with various acids to achieve the correct patina for this piece of furniture that was originally made in 1887. The effort showed his commitment to faithfulness in his practice, since the brackets are completely hidden from view.

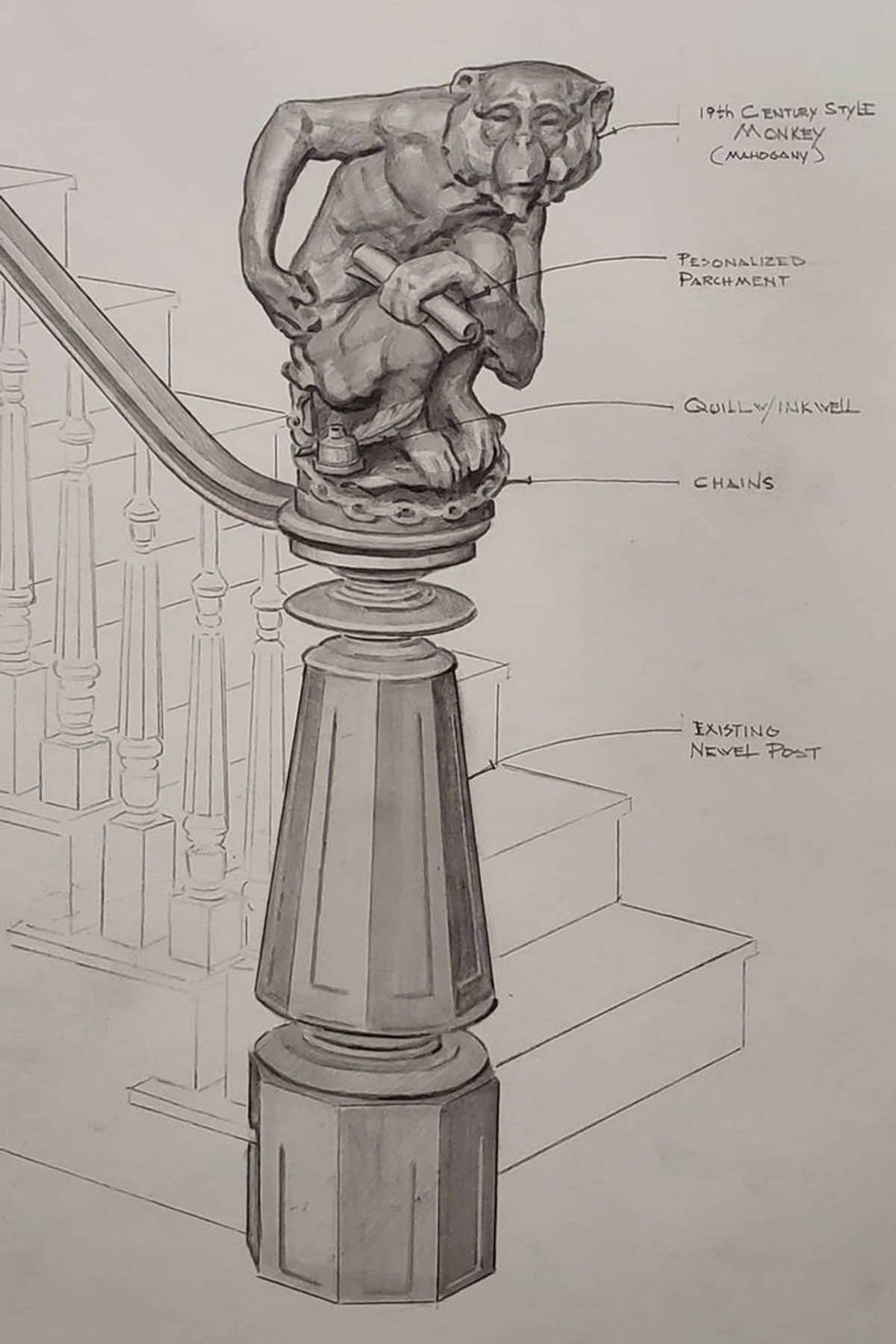

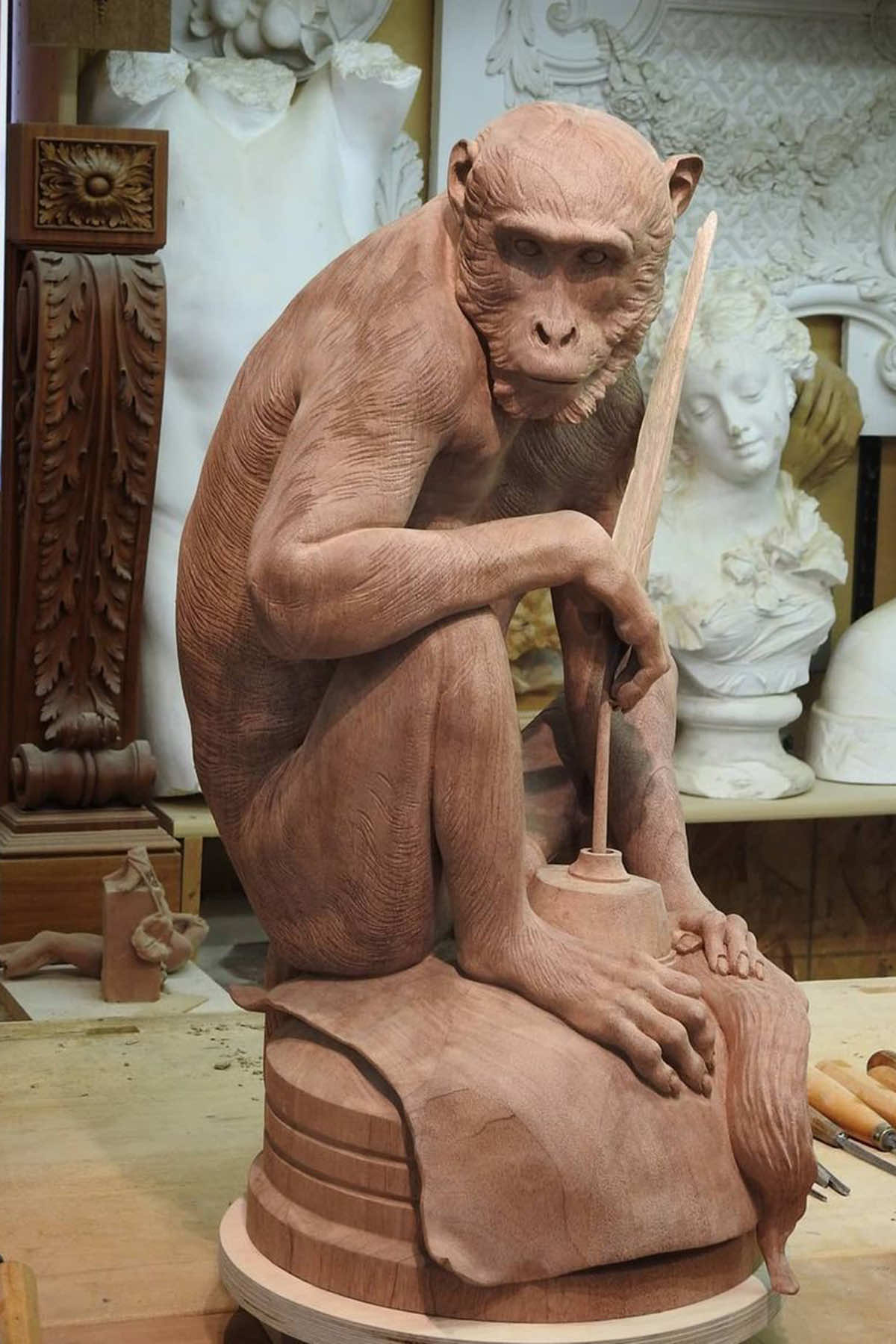

Among his sculptural works, Burke designed and carved several monkey figures out of Mahogany with different poses to represent art, music, philosophy, literature, and love. They now adorn artist Kat Von D’s grand staircase at her house in Indiana. Even the drawings that Burke sketched for his proposal were no simple means to an end, but received similar care and attention to the sculptures that they depicted.

“I put in 12 to 14-hour days in my shop. I think that I am able to do this only because I love the labor itself, and not just its fruits.” – Patrick Burke

Burke was introduced to the chisel at a single-digit age and has been honing his skills ever since. In 2007, he was fortunate to be able to train in the small Italian village of Ortisei, which is renowned for its rich tradition and density of wood carving masters.

Since then, his skills have led him to such projects as the carving of the Seal of the United States for the U.S. Embassy in Helsinki, Finland, as well as creating two Senate throne seats for the 150th anniversary of Canada’s Confederation – which were dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II and produced out of English walnut from the Queen’s forest.

Even though Burke works to preserve “the old ways,” he does not do this because he dislikes all that is new. In fact, he very much enjoys being able to practice his art all over the world with the help of today’s technology since it enables him to effectively communicate with his clients, ship his work to anywhere on the planet, and travel to wherever his projects take him. He also regularly shares his stunning creations on Instagram with his many enthusiastic and international followers.

Instead, he sees the act of conserving the knowledge and skills of the past as a way to retain the full spectrum and wonder of human ingenuity. To stick exclusively to the old ways or to fully adopt the new, while throwing out the old, only enfeebles our choice.

We live in an exciting age in which we can freely mix and match the convenience, cost-effectiveness, and speed of the new with the stunning beauty, long tradition, and viscerally of the old.

“Some of my chisels are over a hundred years old. While using them, I think of the artisans who worked with them before me, what they imagined and what they might have created with them. I feel that I have inherited not just their tools, but their traditions too.” – Patrick Burke

Almost every medium ever invented for recording music is still available today. Almost every photographic process for capturing a moment in time remains in use somewhere in the world. And while 3D printers, CNC machines, and various other robotic devices can create almost all of the objects that Burke has manually carved, his clients still choose the timeless character and aesthetic of the work that his hands produce with chisels that have been handed down to him by the masters who came before him.

Even though the names of many of those masters might now be forgotten, the accumulated knowledge which they have passed down now lives on in Patrick Burke.