After four centuries, how the writings of the Bard of Avon still relate to the contemporary story of local government leaders.

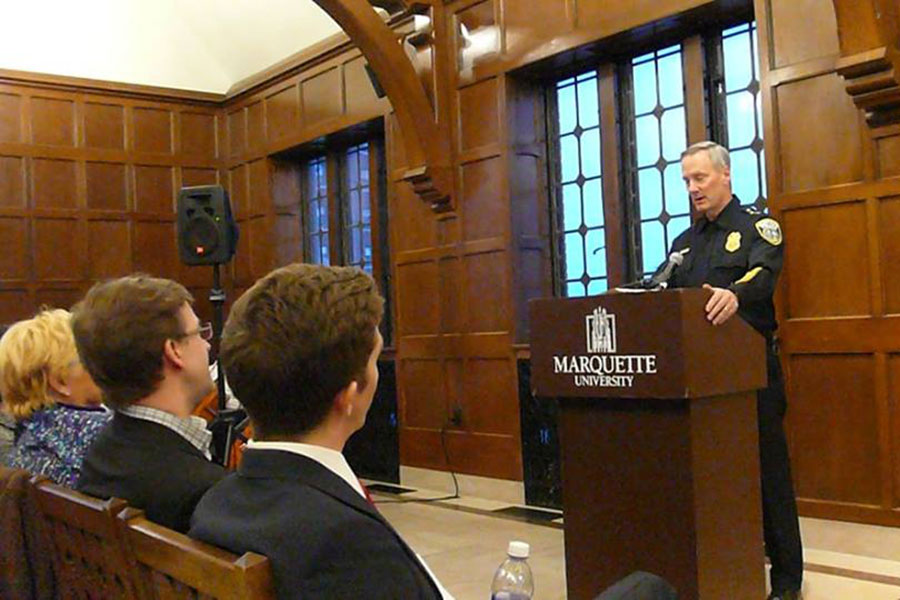

Mayor Tom Barrett played Romeo: “But, soft! What light through yonder window breaks?” Retired Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske gave us Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” with special emphasis on “the law’s delay, the insolence of office.” County Executive Chris Abele and I performed Brutus and Cassius from Julius Caesar: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves.” Chief of Police Ed Flynn as Marc Antony followed with: “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.”

What, you may ask, is going on?

A couple months ago, C. J. Hribal, Marquette English Professor and award-winning novelist, assembled a cast of politicians, academics, and other Milwaukee notables to perform from Shakespeare’s canon. Wisconsin’s poet laureate, Kim Blaeser, recited a sonnet. Marquette professors, faculty, students, and deans presented an array of scenes and sonnets. My personal favorite was Public Radio’s Mitch Teich, who provided Hamlet’s advice to the players: “Speak the speech, I pray you…”

Four hundred years have passed since Shakespeare’s death on April 23, 1616. The anniversary has inevitably prompted the question that will be turned over repeatedly to mark the occasion: how and why has Shakespeare stayed so relevant for four centuries?

But I am more curious to know how and why Shakespeare might be relevant in Milwaukee, to our city and our politics. Also, what might Milwaukee and our politics reveal about Shakespeare—how his plays might be performed, and what they mean.

Shakespeare’s plays are full of incumbents and challengers, victories and defeats, politics and power.

Of recent elections for Mayor or County Executive, we might ask: do these fit the mold of Henry IV and Hotspur, or Richard III and Richmond? Jan Kott, the Polish theatre critic, employed the metaphor of the staircase to depict the ascent and descent of Shakespeare’s heroes and villains in the histories and tragedies. Henry V is always climbing. Lear is on the way down. Both Macbeth and Richard III rise and fall within the course of a single play. To reach the top you must knock off another. But once you reach the top someone else is certain to climb and attempt to overthrow you. “Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself and falls on the other.” And so it goes throughout history. Perhaps politics in our time is no different.

Often in Shakespeare, characters use the discovery of some document or the revelation of some scandal, real or imagined, to advance their political agenda or humiliate an opponent. Polonius uses Hamlet’s letters to Ophelia to win favor with King Claudius. In Twelfth Night, a forged love letter deceives Malvolio into imagining that Ophelia loves him. Malvolio’s humiliation ensues as he plays the fool attempting to woo a baffled Ophelia’s. To take down a political opponent, Iago convinces Othello that his wife, Desdemona, is unfaithful.

In the past election from early April, one candidate’s editorial articles while in college became a significant campaign topic. Another candidate’s police citation turned into a contentious campaign issue. One legislator accused a colleague of uttering insulting comments. “Rumor is a pipe blown by surmises, jealousies, conjectures.”

Shakespeare also addresses civil strife and the dynamics of bigotry and racism.

Might Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet provide insight into the nature of our politically divided state? Do The Merchant of Venice or Othello have something to tell us about bias and racism in our heavily segregated metro area? “Hath not a Jew eyes?” asks Shylock. “Her name,” says Othello, “is now begrimed and black as mine own face.” Both plays are set in Venice. If Shakespeare were alive today perhaps he would have used Wisconsin to set the scene for his political conflicts or chosen Milwaukee for plays that feature the ugliness of racial prejudice.

As much as Shakespeare informs us about our politics, our political insights have much to offer the performance of Shakespeare. Take Hamlet. In recent history, Hamlet, the character, is most often played as brooding, philosophical, depressed, mentally ill, paralyzed by grief or fear or thought. Lawrence Olivier’s 1948 film version begins with a non-Shakespearean line expressing Hamlet’s inaction: “This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” David Bevington, Professor of English at the University of Chicago, details the many ways that Hamlet has been played for the past four hundred years, often in this fashion.

Hamlet is rarely played, in our times, as ambitious, desirous of power, political, and hungry for the crown. This is the manner in which most actors and directors portray the characters Macbeth and Richard III. But Hamlet is ambitious, a prince who wants to succeed his father as Denmark’s king. When Rosencrantz asks Hamlet, “what is your cause of distemper?” Hamlet answers, “I lack advancement.” When Rosencrantz responds by reminding Hamlet that he will succeed the king to the throne, Hamlet responds “while the grass grows” to mean that he is impatient to become king, not to wait. Hamlet later describes himself as “ambitious” to Ophelia. When speaking again with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern he describes Denmark as a prison, Rosencrantz suggests to him that, “your ambition makes it one.” Macbeth hesitates to do away with the king in his pursuit to become king. Might Hamlet’s soliloquys be played in a similar vein?

There is evidence that this is closer to the way Hamlet was played in Shakespeare’s time. Folio versions of Shakespeare’s plays often differ widely from quarto versions, which were published later. The four-hour-long Hamlet we now have is derived from a later version. Emma Smith, Professor of English at University of Oxford, notes that an earlier folio version is shorter, and “Hamlet is a much more decisive character” generating a political “thriller of a play.” David Tennant, in a 2009 film version, approaches the play in this way ever so subtlety by having Hamlet wear the king’s crown and sit on the throne. Tennant’s Hamlet wants to be king, even if just a little.

There is, of course, no single way in which Shakespeare’s plays should be played. Only, as Hamlet says, “actions that a man might play.” This is, I believe, how a politician might play the part — ambitious, hungry for power, but also torn. There is no way to know how to precisely play the part of Hamlet or the role of the politician. But the audience — the electorate — decides which version is best at what time.

Bevington argues that Shakespeare rarely answer questions. Rather, Shakespeare asks questions of us, his audience. He forces us to engage with the questions he raises and develop our own notions, a process akin to how our political process should work for both voters and politicians. Perhaps that is why his works have outlasted him for four centuries. Perhaps that is why in another four hundred years someone in Milwaukee, and many around the world, will again be exploring answers to the fundamental questions that Shakespeare asks us.

Images courtesy of Marquette English – FAME