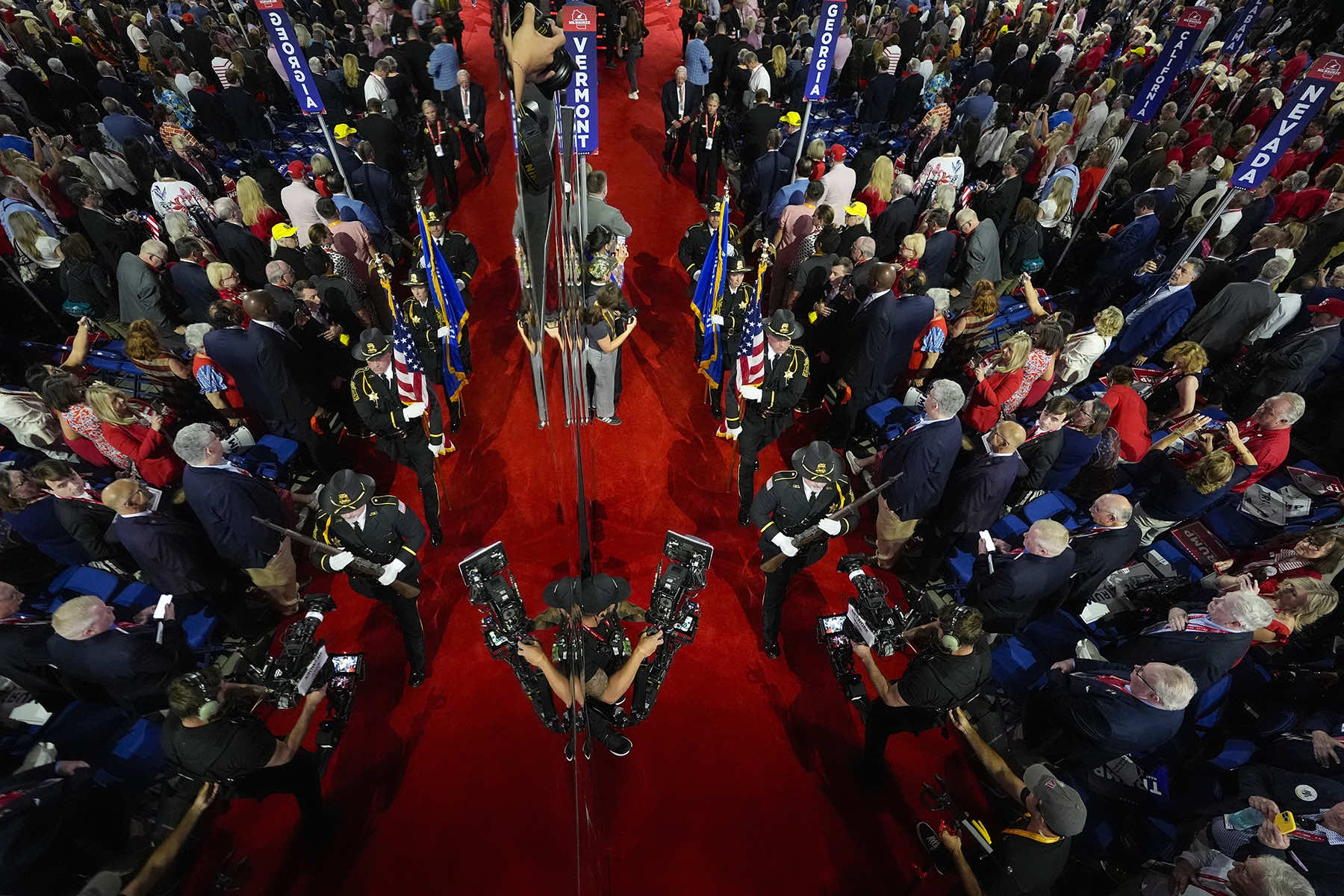

Downtown Milwaukee turned red for the week of July 15 as thousands of Republican National Convention delegates and other party stalwarts gathered in Wisconsin’s largest Democratic stronghold to formally rally behind convicted felon Donald Trump as their candidate for president in the pivotal swing state.

Outside the security zone where the convention took place, residents grumbled, ignored, or shrugged their way through the event that served to galvanize the GOP and give Trump momentum.

Milwaukee’s Democratic mayor, Cavalier Johnson, wasted no time in deeming the convention a success even though he will now turn his focus toward making sure Trump loses in November.

“We demonstrated our city’s capacity to host a major and a massive event,” Mayor Johnson said. “That’s important to the tens of thousands of visitors, and it’s important to the future of our hospitality industry right here in Milwaukee.”

But tallying up the economic impact on Milwaukee will take months and complaints have been piling up, including over blocked streets and storefronts, disappointing restaurant bookings, and the use of out-of-town officers to police the city.

Residents also will not soon forget that Trump described Milwaukee as “horrible” during a closed-door meeting with congressional Republicans last month, though his defenders later suggested he was referring to crime or election concerns.

“I think there are a lot of people that are very upset by the ‘horrible’ stigma that Trump assigned to the city,” Jill McCurdy, a Democratic retiree, said as she strolled through Red Arrow Park, where hundreds protested days earlier. “Certainly people who live here, especially those of use who have lived here all our lives, we don’t see it that way.”

McCurdy, 68, said she hopes Republican visitors came away with a positive view of the city, which sits along Lake Michigan about an hour’s drive north of Chicago, where the Democrats will hold their convention in August.

But after talking to friends who own restaurants and were “pretty disappointed” by business during the convention, she said she was not confident the city benefitted much from hosting the GOP’s big event.

Jay Nelson was standing outside the convenience store he manages in downtown Milwaukee when one of his regular customers walked by on her daily stroll around the neighborhood.

“I’ve been telling people to come and buy even just a bottle of wine,” she said, stretching out her arms. “I hope it helps.”

Pulling her in for a hug, Nelson said they needed all the help they could get.

The store he has managed for nearly a decade, Downtown Market & Smoke Shop, was among the many businesses sealed off by tall metal fencing for the 2024 Republican National Convention, a sprawling footprint that shut down portions of the city’s downtown for more than a week.

For small businesses like Downtown Market, the RNC did not deliver a decisive victory, instead hindering sales despite earlier promises that it would bring an economic boost.

“I want you to take all your money to Milwaukee, spend it that week, and leave it in Milwaukee,” Mayor Johnson said two years ago at the RNC’s summer meeting where it was announced that the city would host the GOP’s national convention.

But Samir Saddique, owner of Downtown Market and the neighboring Avenue Liquor, said the convention brought “a lot of nothing.” Traffic and sales took a nose dive soon after the fencing went up in front of the stores. By July 18, the RNC’s final day, the liquor store had made just 10% of its usual sales, he said.

“We’re barricaded away from the rest of the world,” Saddique said.

Across the Milwaukee River, which marked the eastern edge of the RNC secure zone, just one seat was taken at the bar inside Elwood’s Liquor & Tap during their July 17 happy hour, which is usually a reliably busy night for the red-booth bar near Fiserv Forum where the convention’s main stage was housed.

“Everybody was promised that this was going to be a giant moneymaker for businesses,” bar manager Sam Chung, 30, said. “So it’s strange seeing how much it’s actually killed business for a lot of people outside the perimeter.”

Even their most loyal customers had not stopped by during the RNC week, Chung said.

“They don’t even want to come down here because it’s obviously a mess to get here,” she said, adding that she thought “a big part of it is that a lot of our regulars are Democrats.”

Adam Buker, a 21-year-old barista at a coffee shop near one of the convention’s exits, which leads attendees onto a wide-open street, said that while the RNC was in town he had been playing music by queer artists as his own protest. Yet the door kept swinging open at Canary Coffee Bar.

“It 100% has to do with our location,” Buker said on July 18 as he packed espresso grounds for a cortado, with a Frank Ocean track playing in the background.

Though it was outside the secure zone, the cafe’s glass storefront and buttery yellow sidewalk seating were not obstructed by the fencing like Saddique’s liquor and convenience stores were. RNC attendees also did not have to cross the river to get to the coffee shop, unlike Elwood’s.

Democrats must perform well in Milwaukee in order to counter Republican strengths in more rural parts of Wisconsin. Trump narrowly won the state in 2016 before losing it to President Joe Biden four years later by only about 21,000 votes.

Wisconsin is one of only a few true swing states that could go either way this election and will determine who wins the White House. Four of the past six presidential elections in Wisconsin have been decided by less than a percentage point.

As Tyler Schmitt, 28, and his partner Ken Ragan, 24, stretched in the long grass on July 17 at a park west of the convention site, they considered the pros and cons of Milwaukee hosting.

Ragan said she could do without the traffic headaches. But Schmitt, an urban farmer, said he sees positives.

“From a small-business perspective, it brings good energy in the tourism and good press,” he said. “It’s pretty much downtown, and I think downtown is appropriate.”

But the downtown location still put law enforcement, including visiting officers from across the country, on Milwaukee streets. On July 16, officers from Columbus, Ohio, shot and killed Samuel Sharpe, a man who had been living in a homeless encampment about a mile (1.6 kilometers) from the convention site.

Sharpe had a knife in each hand and moved toward another man, ignoring the commands of police officers before they shot him, authorities said. The shooting remains under investigation.

Sharpe’s sister, Angelique Sharpe, blamed his death on the presence of out-of-state officers.

“I’d rather have the Milwaukee Police Department, who know the people of this community, (than) people who have no ties to your community and don’t care nothing about our extended family members down there,” she said.

At a rally after her brother was killed, Angelique Sharpe said her brother suffered from multiple sclerosis and was acting in self-defense against a person who had threatened him in recent days.

Activists in the city also questioned whether the focus on the convention had minimized more pressing, systemic problems in Milwaukee.

Hours before Trump took the convention stage July 18 night to deliver his speech to delegates, dozens of protesters held a rally a block from the convention site to call attention to the deaths of Sharpe and another Black man, D’Vontaye Mitchell, who died last month after he was pinned down by security guards at a nearby hotel.

“They come here and make money off our city. But when we’re hurt and we need them, they’re not there,” said Karl Harris, Mitchell’s cousin.