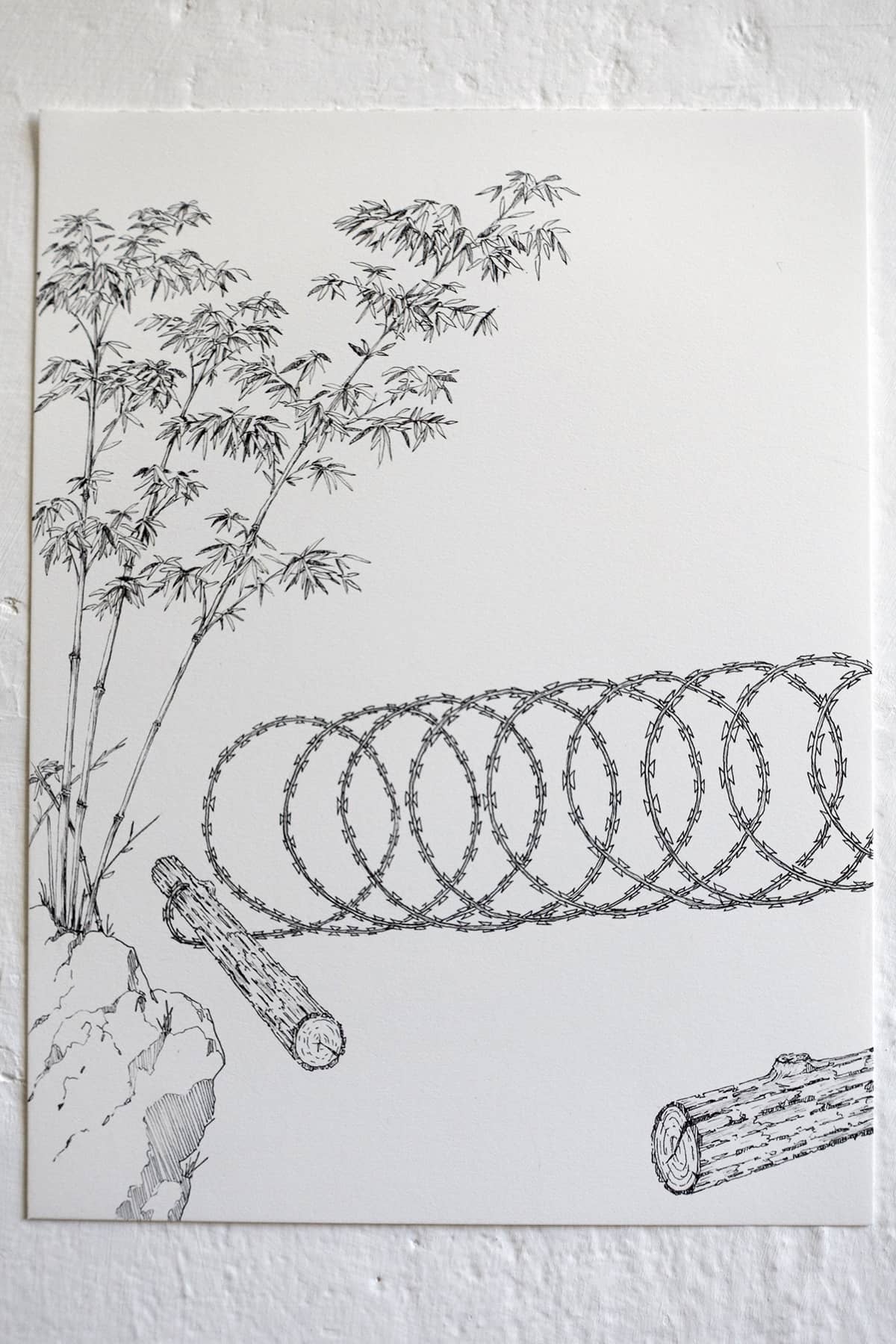

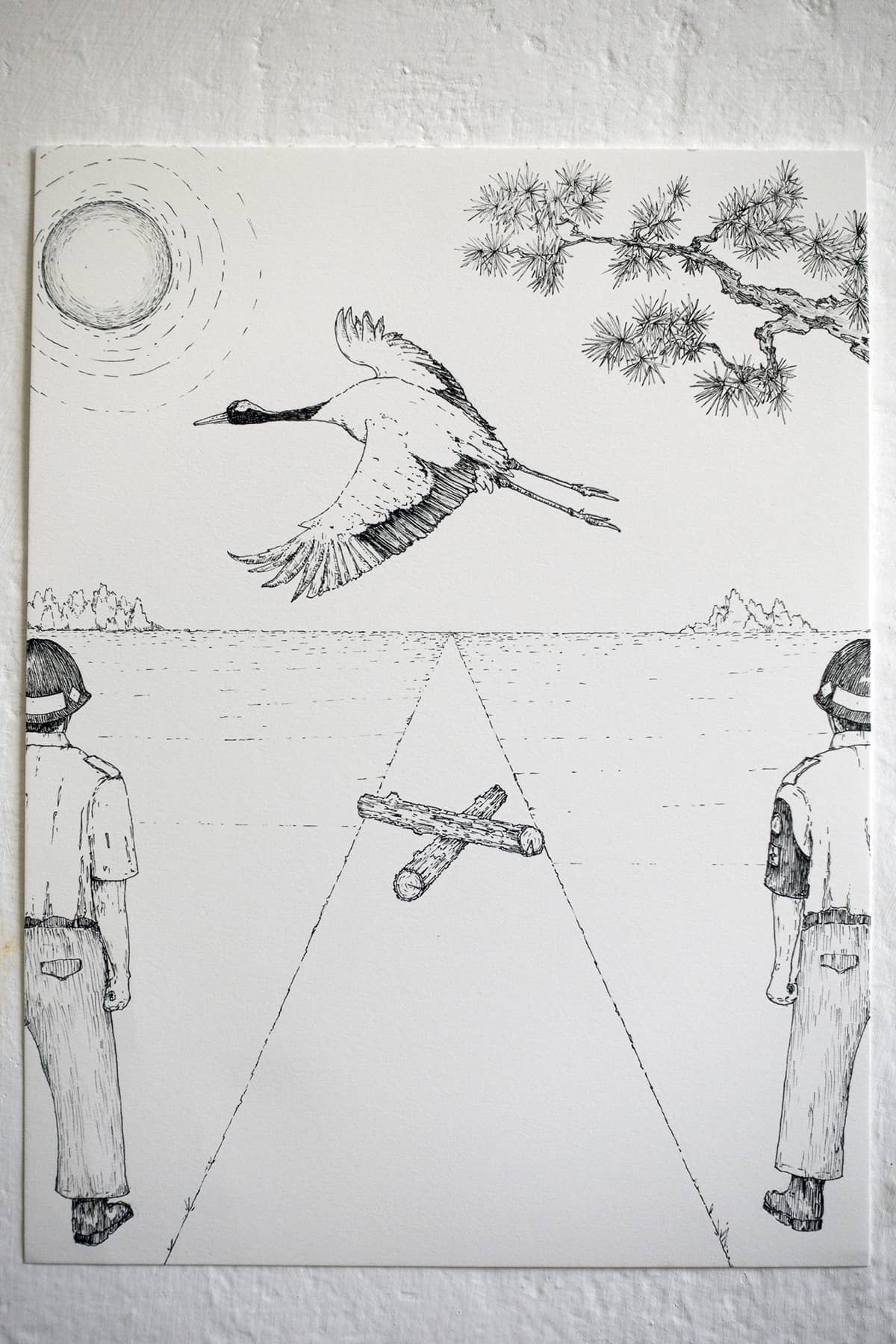

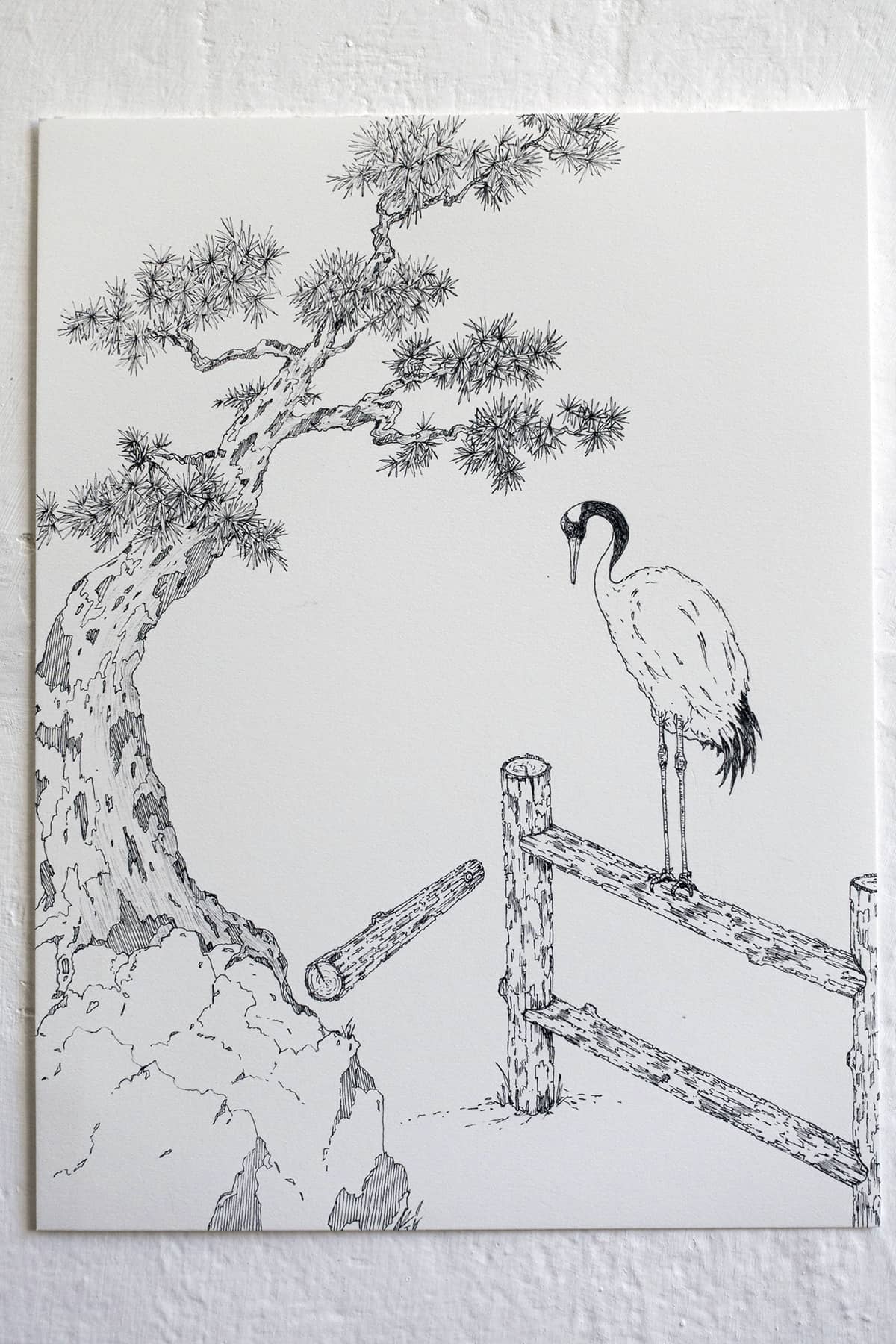

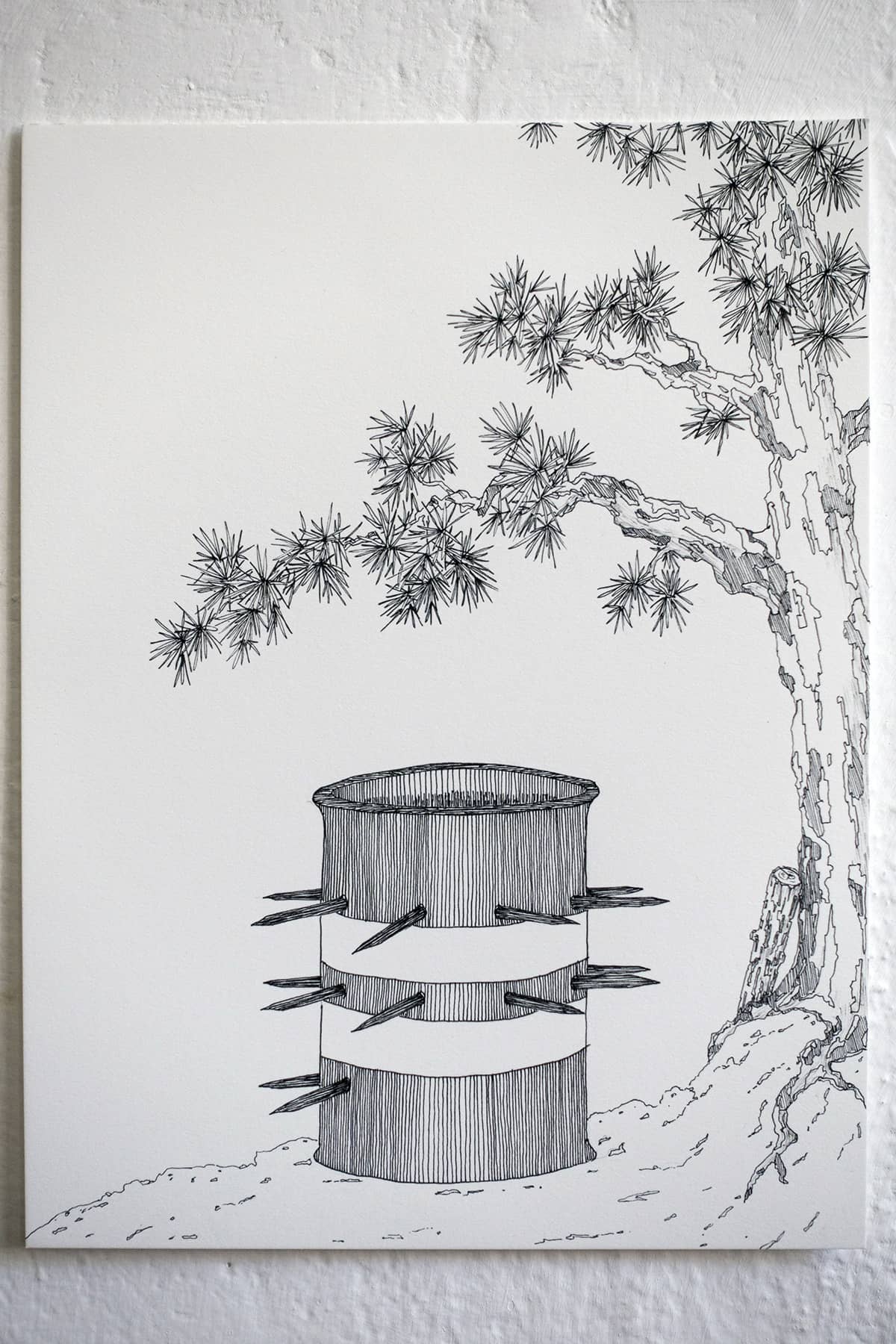

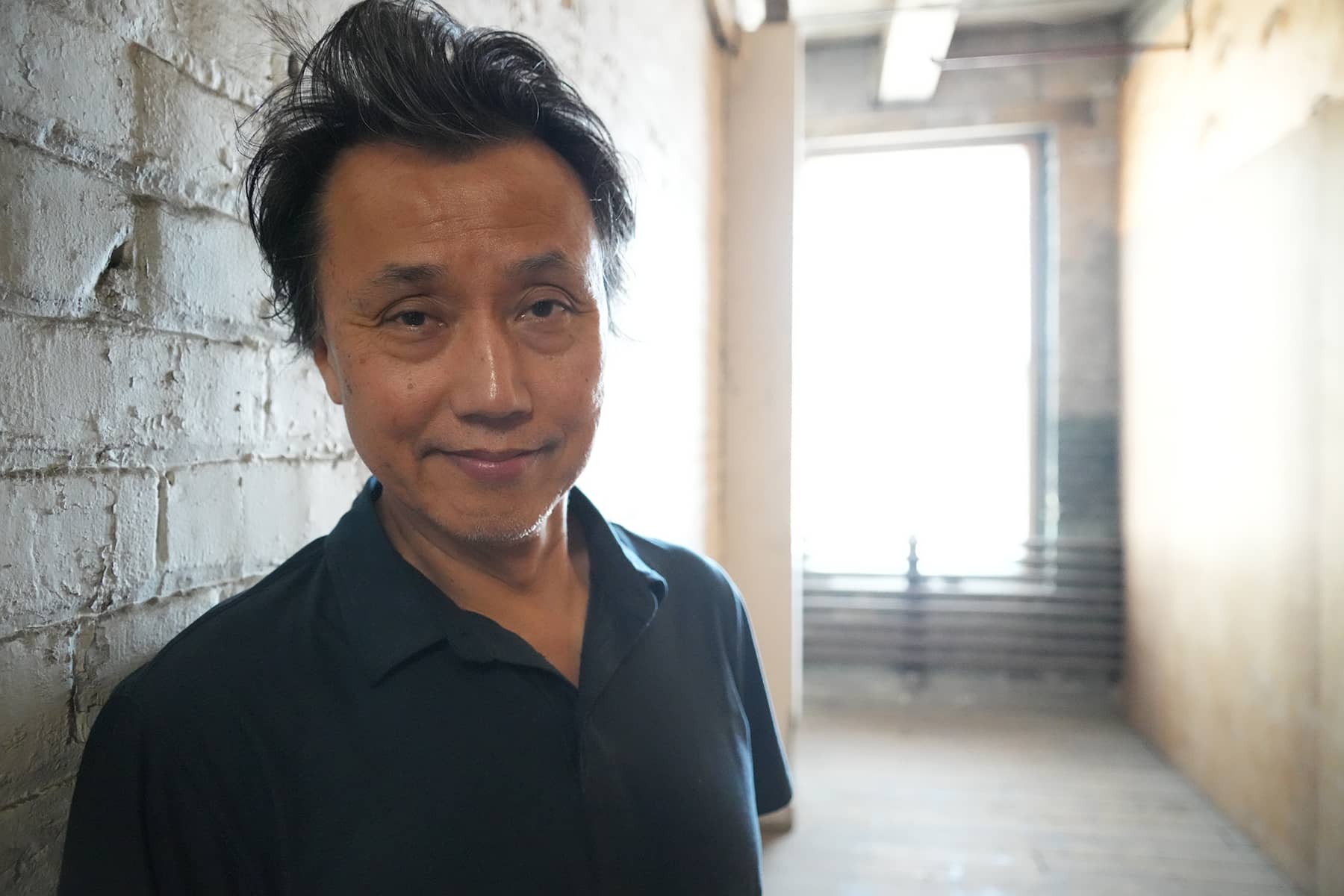

The artistic work of Jason S. Yi explores the meaning of identity and culture. His blending of creative disciplines often reflects the deep influence of his journey from South Korea to the United States.

Yi’s childhood in Seoul was rooted in tradition and art, which would help shape his understanding of the world beyond his neighborhood. Those formative years also fostered his joy of nature. Some of his happiest memories involved spending time with his family by a small river.

“I can’t even recall where it was, but I would go to a stream with my family. It was always cold, but it was a very peaceful place,” said Yi. “Sometimes I would go to the stream alone, but I enjoyed being there most with my family.”

His father worked for the U.S. government on an army base, doing different types of creative work. Yi was curious to see what he might be able to bring home for the family.

“Oftentimes he would bring us American rations, which came in a green can. And of course, there were some markings on them but I didn’t know how to read English. So every time we opened the can, it was always a surprise,” said Yi. “We didn’t know what was inside of it. So sometimes it would be crackers, sometimes it would be cheese. Our favorite was always cheese. Or there’d be cookies or sweets or chocolate. So those are the memories that I remember most, of my dad bringing home these amazingly different types of food. It almost always felt like Christmas.”

Yi’s father grew up near Pyongyang during the Japanese occupation. He always liked to draw and to do creative things using his hands.

“He didn’t have that much money, but somehow he found a way to study art in Japan. Then when the occupation ended and the Korean War broke out, my dad was kind of stuck there,” said Yi. “But also it was not safe to come back to his hometown during the war times.”

Yi would look forward to his father’s arrival from the U.S. base each day, but it was always a long wait for him to come home.

“He would do everything from drafting to graphic design, and he would even make these unique Christmas cards. And he would paint it all because my dad was an artist. So they trusted him to do creative things,” said Yi. “I would not see him a lot, because he’d leave early in the morning and come back probably around seven or eight o’clock at night.”

While reflecting on his youth, Yi admitted that his mother did pamper him a bit because his father was always working.

“She was a very strong-willed lady, and she took me everywhere. Back then we just had the bus systems, and it wasn’t very efficient. It would take my dad an hour to commute home. Which also involved him changing buses a few times,” said Yi. “It was usually me hanging out with my mom. I was the youngest of the four, so I think that’s why she favored me at times. In my early years, my Mom was a big influence on me. Then later, when I came to the United States, it was my dad.”

The shadow of the Korean War still loomed over Yi’s family into the early 1970s, with stories handed down from parent to child. It had been a traumatic time for his father, who never talked about the experience. His mother grew up near the border at the 38th Parallel in Gangwon-do, experiencing firsthand the harsh realities of the conflict.

She had two sisters and four brothers. All four brothers died, either passing away from the war or through disease. It was a really rough time, with only the three sisters remaining alive during the war.

“My mom lived in what used to be a poor farming province on the east coast of South Korea. It was known as a potato province. She was the middle sister. One time she told me that her older sister was married to a South Korean colonel during the war,” said Yi. “When North Korean soldiers invaded her town, they lined up all the townspeople including her sisters. They were saying to the people things like, ‘We know there’s somebody here married to a South Korean officer. Who is it?'”

The townsfolk were being interrogated and threatened. People were dying all around them in the war, so they knew things could turn very violent very quickly.

“They identified my mom’s older sister and asked, ‘Are you the one?’ My mom vividly remembers going up to the soldiers, grabbing her sister, and saying, ‘No, she’s married to a person in town here. She’s my only sister,’ which wasn’t true. But it worked.”

Yi said that his mother’s intervention saved her sister’s life that day, because the North Korean soldiers were planning to shoot her.

“That story and others she told me when I was a boy had a real impact on me, just thinking about how I would react in that kind of situation,” said Yi. “Would I be as brave as my mom, and courageous as my mom, and think on my feet like she did?”

Yi was glad that there was a resolution that brought an end to the fighting, but he still felt conflicted. No peace treaty was signed, so the two nations are still at war. It was a bitter pill to swallow, knowing that South Korea had almost won the war and would have reunified Korea into one whole country again. But the Chinese invasion prevented that. To Yi, how the war ended felt arbitrary and incomplete.

“I also remember walking to my elementary school, as a third grader or fourth grader, and I would see the aftermath. But I was clueless that it was related to the war,” said Yi. “I was eight or nine years old and I would walk past these bombed-out buildings still in the middle of Seoul.”

He said that on some nights, but not often, there would be missiles going up into the sky as tensions flared with North Korea. To Yi at the time, they seemed joyful to behold – just like fireworks. He would watch in awe as they streaked across the sky, but had no concept of what their purpose was.

“So as an adult in hindsight, all those things are really crazy and traumatic in the way they influenced how I think about the war, how I think about these sorts of divisions that people have,” said Yi. “It’s all based on ideology, based on what’s been ingrained in their thinking. That’s changed over time, through brainwashing or whatever it may be, how extreme people can get.”

At the age of eleven, Yi’s life took a dramatic turn when his family of six moved to the United States. It was a difficult journey to leave behind everything familiar and step into a completely different culture.

“We moved to the Washington DC area because we knew somebody. I think a lot of Koreans in the late 1960s and early 1970s moved there because of it being the capital. There was a huge population of Koreans living in DC,” said Yi. “I remember my dad showing me the letter from the State Department saying we had been invited to immigrate to the United States. My dad served at the U.S. Army base for about 20 years working for the U.S. government. So I felt the invitation was a reward for his service.”

Being the youngest of his siblings, Yi was more receptive to their new environment. But he was not unaware of the hardships his family faced with language and a different culture.

“My older siblings had a tougher time because they were a little bit more mature. They worried about other things that were happening around them a little bit more than me,” said Yi. “I think for me, the culture shock that I experienced was literally me having to go to a new school in the U.S. a week after I landed. They put me in a class and I didn’t know a lick of English.”

But Yi accepted the challenge, knowing that his language skills would come in time. And while he could not speak English, he could still excel in other subjects. Numbers are universal, and South Korea taught at a higher level than comparable grades in America. So when it came to math, Yi found himself ahead of his new classmates.

“When there were math problems, it was super easy for me,” said Yi. “I remember all the other kids kind of gathered around me asking, ‘how did you solve it?’ That was a moment when I realized there are certain things we all have in common.”

It was also a moment when Yi understood he needed to get better at English. What little he had learned had come “on the fly,” and he wanted proper instruction. He was fortunate to find a tutor who was a student about his age. Determined to improve, Yi would stay after school every day to learn English.

“Most people were super nice to me. They understood that I didn’t understand anything, so they were very patient with me,” said Yi. “I’m still amazed that I got through all that, all those experiences, just being in an elementary school in the 1970s.”

While Yi still held onto his Korean traditions, he embraced the culture of freedom he found in America. He said it was an expansive country that allowed him to explore beyond his immediate boundaries.

“Maybe two or three weeks after coming here, I learned how to ride a bicycle. I had always wanted a bicycle to ride, but I never had the opportunity,” said Yi. “And once I got that bicycle, I felt like I could go anywhere. I thought, ‘This is freedom.’ Where I grew up in Seoul, you didn’t really do that. There were still bombed-out areas and people drove cars really crazy. So I saw the environmental openness of America. Even if I could only get around a few miles at a time with my bicycle, it was still far for me.”

As Yi’s family settled into their American life, there were lessons from the struggles they overcame. Yi’s father spoke the best English in the family because of all the years he worked with Americans. But in hindsight, Yi realized his father was not very fluent and just barely got by.

His father wanted to do creative work, and ended up with a graphic design job for a printing company producing silk screens. It was definitely a step down from his previous type of work. But at the time he did not know enough English to become acclimated to the American workplace environment.

“When I saw that, I saw the level of perseverance that he had in making things work creatively. Yet at the same time, he worked just as hard in America as he had in Korea. Probably even more so in America just because of all the hardships with language barriers, cultural barriers, and things like that,” said Yi. “So I think witnessing that influenced me. Also, me seeing him draw and paint ever since I was a child, that carried on over to the United States.”

Yi moved to Milwaukee in 1996 for a position to teach at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. In his youth, when he first started to draw, Yi did not remember his father encouraging him to be an artist. To support the family he was too busy earning money. He also knew it was a difficult and challenging career to be in. Watching his father’s example of perseverance helped Yi to reinforce his commitment to being creative.

Generations of immigrants have left their homeland to start over in the United States, following the American dream. But not all the baggage they brought with them could be carried. When Yi reflected on the complexities of his cultural identity, he acknowledged that navigating life – being both Korean and American – was a tough and fluid concept.

He believed that America was built by foreigners, on the idea of being a land of immigrants. He also felt that even though he did not resemble those early European settlers from the past, he still belonged.

“America is my country too. And I can tell myself, ‘I am an American.’ But I also remember when I was in college, going back home to see my parents, I knew I was walking into a Korean household,” said Yi. “I had to speak Korean, I was not required to – I spoke Korean because they understood Korean better than English. There were also traditions that I needed to adhere to. So I think I adapted in that way, sort of a duality of how I need to behave in certain situations.”

Understanding the duality in his life, Yi learned to accept the cultural expectations of different environments. He realized that moving between the two identities was not just normal but even empowering. He believed that personal identity did not have to be confined to one category or another. The flexibility of his identity has led him to feel less conflicted and more at ease with who he is.

“There are a lot of people who are thinking about their cultural identity, but I also think that’s maybe becoming an outdated notion,” said Yi. “I’ve seen plenty of young people struggle over it too, it’s like, ‘Where do I belong?’ I think it’s okay to feel like I don’t belong with any group.”

In his school days, Yi did encounter name-calling from other kids, whether it was shouted from a distance or spoken directly to his face. The experiences served as reminders of how some children, in their ignorance, could be hurtful. While he could recall specific instances, the general feeling was one of being singled out for his differences.

Even though such incidents did not occur every day, Yi would feel a certain pressure or a sense that he stood out from others around him. Those feelings of being different extended beyond school. He remembered how, whenever he visited rural areas in Wisconsin and entered places like supper clubs, he would immediately sense all eyes on him.

“You can get really self-conscious and before you enter, you think about being in an environment where you are not like anybody else there,” said Yi. “So when people talk about privilege, that’s part of it. The privilege is you don’t need to be aware of the environment that you’re in. But also, when you get stared at, it doesn’t mean they’re racist. You’re different.”

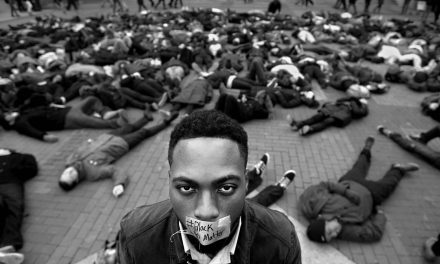

Definitions of discrimination and racism are constantly evolving. Yi sees that evolution as inevitable, influencing how the issues are identified, recognized, and manifested in people’s behavior.

“I have a biracial daughter, and my wife is White. My daughter has adjusted remarkably well to her identity. She doesn’t dwell on it too much, but she is fully aware of who she is. I believe it’s important for her to have confidence and acceptance in that,” said Yi. “As a teacher, I interact with young people all the time. Everyone’s experiences and perceptions are unique, which shapes how they interpret the way others treat them.”

He pointed to the understanding of “microaggressions” as an example. It was a relatively new concept, the term did not even exist 15 or 20 years ago. Now it is an important part of the conversation on discrimination.

“I feel like my life is pretty much an open book. My world revolves around three main things: my family, art, and teaching. These three aspects occupy most of my mental space, and I don’t really hold much back. What you see is what you get,” said Yi. “Sometimes, I think people are surprised by that. They might expect that there’s another side to me, something hidden or more guarded. But in reality, everything’s out there for people to see, there’s nothing left behind the curtain.”

Over the years since he started a new life in the United States, Yi has returned many times to Seoul. He was there last in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic. The changes he witnessed were nothing short of night and day.

“When I visited South Korea about 10 years ago, I wanted to return to the house where we had lived. I clearly remembered it was a long walk up a hill with our house at the top of it,” said Yi. “Of course, everything had changed since then, except for our house. The entire neighborhood had been replaced with buildings I didn’t recognize. But our old home was still there, still intact. I could not believe that was the place where I grew up. I was just amazed at the amount of progress that South Korea has made.”

Yi said his mom had not been back to South Korea for a while prior to that visit. When she landed, she was actually a bit scared. She spoke Korean better than Yi, and she spoke Korean better than English. But she felt out of her element when she came home.

“For her, it was a different country. Everything looked different. Everything looked modern. Everything was so much more fast-paced,” Yi added. “I remember getting into a taxi with my mom. And my mom said, ‘Can you ask the taxi driver where this place is?’ And I said, ‘Mom, you know Korean better than me. Why don’t you just ask him?’ But she was afraid to ask, to interact with Koreans, even though she was more Korean than I was. That’s how much her homeland had changed.”

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora