On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the best known speeches in American history, at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This essay is part of a series of opinion pieces. Each one is no longer than 272 words, the length of Gettysburg Address, and responds with a view of how Lincoln’s spoken ideas in Gettysburg are relevant to America in 2017.

Seven score and fourteen years after the Gettysburg Address, this nation fights the same war that raged then. The rules of engagement have changed. Today’s battlefields do not resemble those of the 1860s. But the fundamental struggle is unchanged. On its resolution turns the question, still open, of whether our government, of, by, and for the people, will persevere or perish.

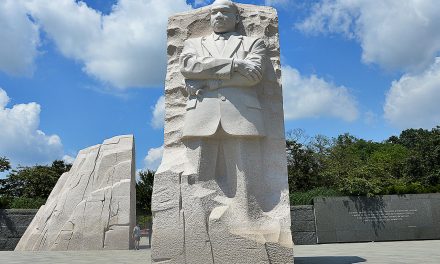

The constitutional amendments and civil rights statutes created in the 100 years after the Civil War are not themselves the “new birth of freedom” of which Lincoln spoke. Enforcement of these laws has empowered some to rise above discrimination to heights undreamed of before their inception. Yet, the underlying spirit of equality and freedom never fully entered the national psyche as a unifying principle. The nation remains divided, and dangerously so.

Look at the disparity of wealth in this country, and the millions trapped by poverty in our ghettos. Look at case after case after case of deadly police brutality against African-Americans, spreading like a pox across the landscape — not a new phenomenon, but one of which technology has only now promoted widespread consciousness. Look at the xenophobia gripping the nation, the rise of hate speech, the resurgence of hate groups, the omnipresence of battlefield weapons on our streets. Look at the election of leaders who turn their backs on all this. Then ask where the “new birth of freedom” is. Lincoln would not speak; he would only shake his head.

America, that bastion of power, has yet to become what it was meant to be. None of us are truly free. We must all increase devotion to that cause.

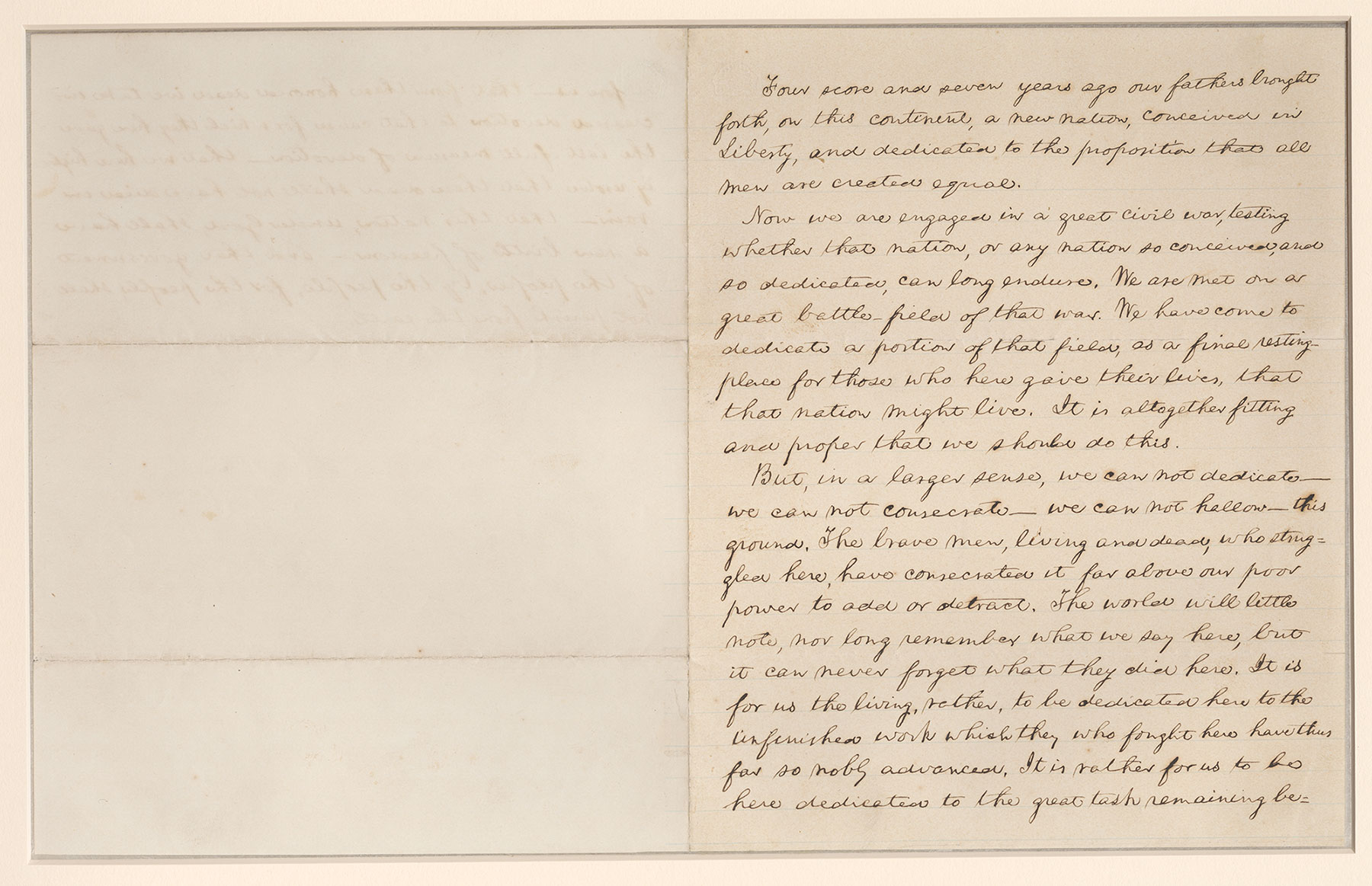

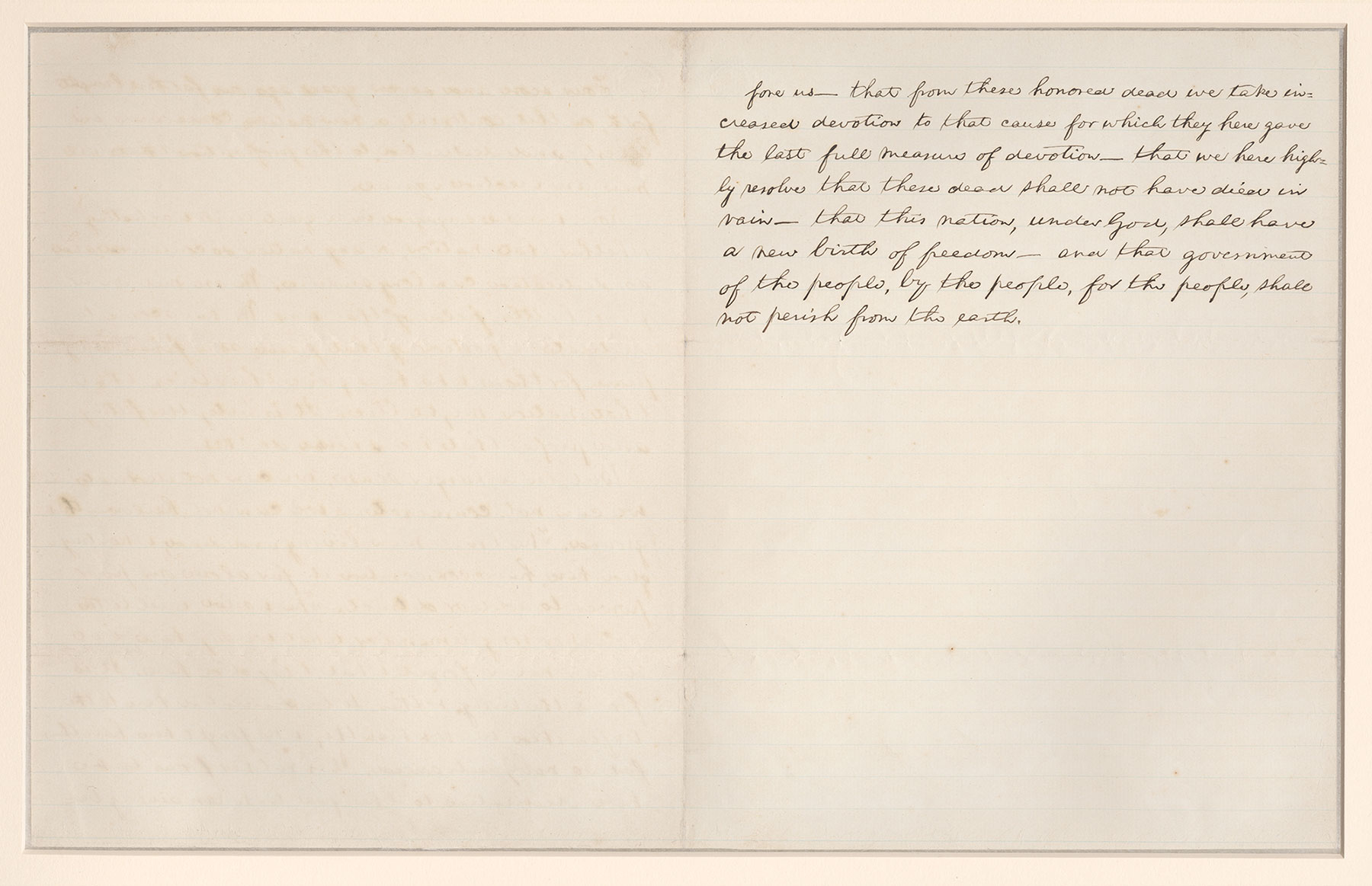

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (The Bancroft Version)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Cornell University Library’s copy of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of five known copies in Lincoln’s hand. Written out by President Lincoln at the request of U.S. historian, George Bancroft, this copy, the fourth that Lincoln composed, is known as the Bancroft Copy.

Charles H. Barr is a local attorney and editor of the Milwaukee Bar Association quarterly publication