Two years ago on March 22, 2020, COVID-19 closed access to public buildings, but not to the courts within them. When the Wisconsin Supreme Court ordered the suspension of nearly all in-person hearings, the Milwaukee County Circuit Court already had geared up for the impending justice system slowdown.

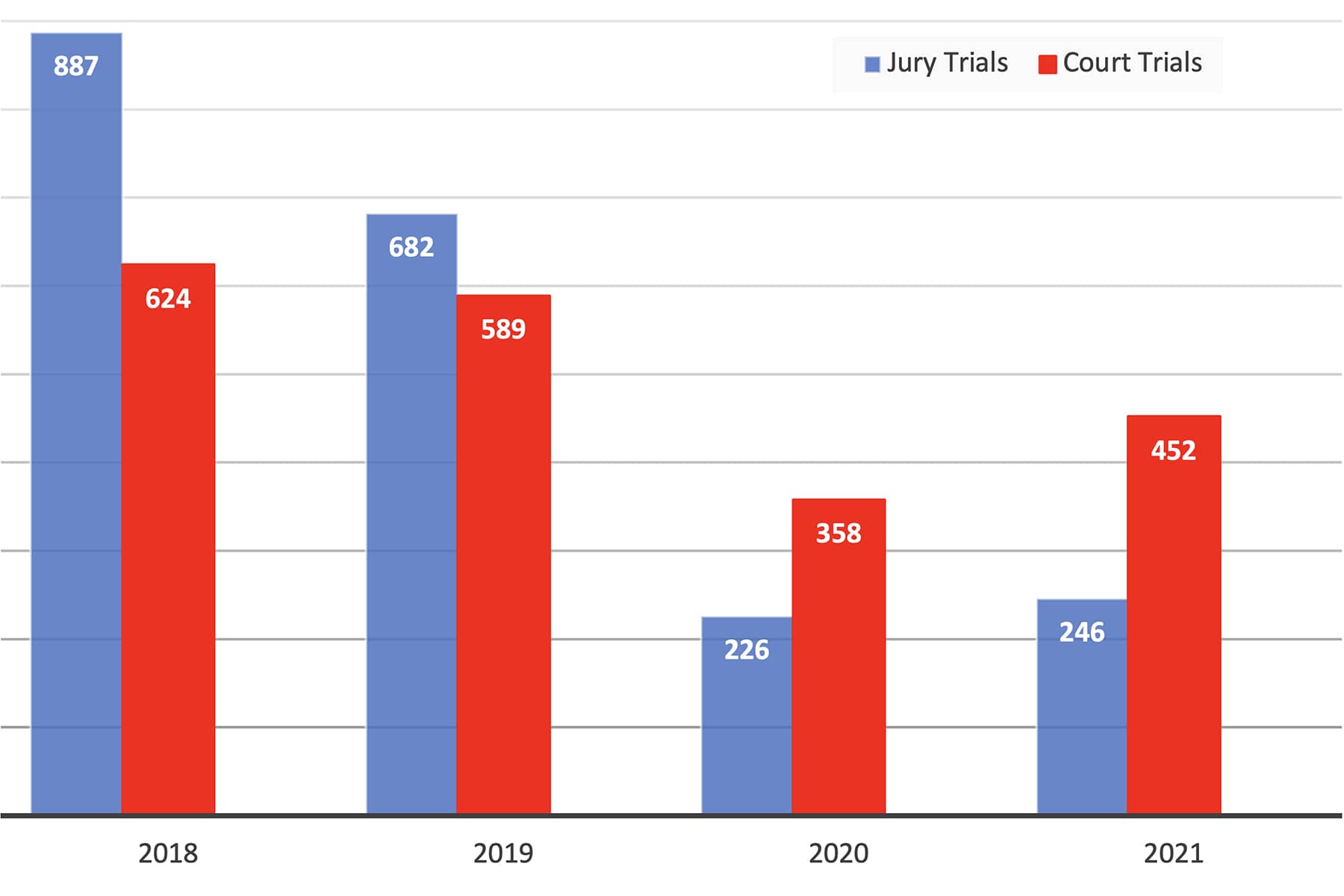

By pivoting away from in-person appearances to pandemic-safe Zoom “courtrooms,” the local justice system never ceased hearing cases. Two years ago, the 4600 persons daily entering the Milwaukee court facilities were reduced by 85% to fewer than 700 essential workers and litigants involved in the most serious criminal cases and domestic violence-related cases. For months, none of the annual 13,000 summoned jurors were called to service. Hundreds of the more than 12,000 annual criminal case charging decisions and filings were deferred, later resulting in a 33% increase of pending felony cases between end-of-year 2019 and end-of-year 2020. Eviction and mortgage foreclosure case filings surged, due to and despite the federal temporary moratoriums. These filings did not offset the 43% fewer pending criminal traffic matters at year’s end between 2019 and 2020.

As the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic begins, the courts have shifted back fully to in-person hearings and jury trials – still observing mask, social distancing, and other public health protections and precautions. However, the local justice system faces two major, COVID-19-residual challenges. The first challenge is managing the substantial backlog of COVID-19-mitigated cases. At the same time while they reduce backlogged cases, the courts must keep in check the rising number of new case filings. Currently they outpace previous annual case filing statistics. The second post-pandemic challenge is staffing the tremendous number of employee vacancies in critical court positions and jobs. Success in clearing the backlog is dependent on retaining and recruiting talented persons to this specialized work.

Processing thousands of pending cases along with the over 100,000 annual newly filed cases took its own toll on court staff, system partners, and private attorneys. They all faced many of the same COVID-19-related issues as other essential workers faced in other work sectors. And like other employment sectors, the courts were further stressed by and not shielded from the Great Resignation.

Since March 2020, 17% of the Milwaukee Circuit Court judges (8) resigned or did not seek reelection. Pre-existing court reporter shortages were exacerbated by the pandemic. Today there are forty-six persons “keeping the record” for forty-seven judges. As of March 2022, deputy court clerk vacancies total sixty-four. Pre-pandemic, eighty-four bailiffs were budgeted for the courts. Currently, about 50 are in service. Statewide, overwhelmed front-line attorneys left in droves from district attorney offices and State Public Defender offices. For every new hire there is a specialized “on-boarding” that takes time, delaying relief for the current court professionals. Adequate staffing in all court roles is necessary for proceedings to be Constitutionally sound, and timely heard.

On March 15, 2022, Governor Evers announced a statewide $56 million “Community Safety Package “of federal ARPA funds, with $20 million targeted for Milwaukee County and the City of Milwaukee. The grant package includes specific court system allocations to expand pretrial GPS monitoring ($283K), to formalize Milwaukee County’s Mental Health Treatment Court ($265K), to expand court operations to accelerate clearance of the criminal case backlog ($14.5M) and to launch a pilot project extending courthouse hours and operations two days per week ($119K). The funded strategy depends on designating and staffing five more of the forty-six trial courts as criminal courts.

The largest share of funds is earmarked to increase the number of clerks, court reporters, and other essential court staff. Only well-trained, fairly compensated public servants can efficiently reduce the backlog and successfully advance the mental health court. The Community Safety Package also allocates funds statewide for district attorney office staffing ($5.7M) and State Public Defender teams ($5.5M). Without the increased staffing and operational funds, it would take several years to wipe out the current criminal case backlog. With the funds and enhanced staffing, the expectation is to clear the backlog within eighteen months. And justice, therefore, is more timely served.

Milwaukee County Circuit Court Jury and Court Trials: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic 2018-2021

TWO YEARS OF COVID-19 MITIGATION AMID ONGOING LITIGATION

Weeks before the World Health Organization’s March 11, 2020 pandemic declaration, the Milwaukee County court administrators began COVID-19 contingency plans. Public health concerns were added to the common mix of the courts’ priorities – public access, public safety, public hearings, public records, and in-person proceedings. Indeed, public health became the overarching priority of court operations. The Medical College of Wisconsin appointed a doctor to advise the Milwaukee County courts on mitigating disease spread and best-practice protocols – during an ever-evolving pandemic.

In early March, anticipating an assumed temporary lockdown, judges began rescheduling cases for May 2020 hearing dates. Two new court dockets were created to be heard in two courtrooms isolated for maximum protection from the virus’s spread. The County’s forty-six judges searched their case dockets to find pending and newly charged cases in need of immediate rulings. These cases were funneled to newly created Branches 7000 and 9000.

The judges held regular teleconference meetings to identify critical, pandemic-sensitive issues – including the most efficient way to transition to remote hearings. As “essential workers” court personnel were e-mailed personal “letters for travel” in case stopped by law enforcement during the yet-to-be-established travel restrictions. A closed wing of the House of Corrections was reopened and outfitted for segregation and care of COVID-19-positive inmates. Domestic violence cases and the most serious criminal cases and charges continued to be heard in person.

The emergency created urgencies. Suddenly previous philosophical and economic hurdles gave way to necessity. The long-debated pros and cons of introducing remote hearings gave way to a surge in laptop purchases for judges and court personnel. Judges and commissioners created individual accounts for court record access and for free 40-minute Zoom sessions. Within days, 400 Zoom videoconferencing software licenses were procured statewide to retool the system for all seventy-two counties. Judges and court staff then were able to securely conduct remote proceedings. To maintain the primacy of public access to courts, individual judges created YouTube accounts, later followed by court-based YouTube accounts, and eventually replaced by a state-based live streaming system.

The complexities and interdependencies of the justice system emerged. The county and various elected county officials run the jail, the House of Correction, the three buildings housing the courts, the clerks of courts, and jury service. Meanwhile, judges, court reporters, the Department of Corrections, pre-trial services, probation and parole divisions, district attorney’s office, the State Public Defenders office, and the Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility work under various state authorities. Elected officials, private attorneys, bar associations, and citizens as jurors and witnesses are integral to the system but also independent from government operations. Independently and simultaneously each entity was setting up service and employee policies addressing personal and public safety, quarantines, and emergency leave and coverage.

The decision of one official created a ripple effect throughout. For example, the Department of Corrections decided to suspend transport of inmates to and from state prisons in other counties. Sentenced state inmates remained in the Milwaukee jail despite the need for COVID-19 mitigation of the rest of the jail population.

The Supreme Court’s March 22, 2020, orders set conditions and timelines that periodically were adjusted as the public health crisis continued. Its first order suspended all in-person circuit court hearings, with limited exceptions, and instead required that court hearings be held remotely using available technologies. The order, set to expire on April 15, 2020, was extended “until further order of the court.” The second Supreme Court administrative order suspended all jury trials through May 22, 2020, in order to mitigate virus risk within the courts usually filled with the public, witnesses, summoned persons, jurors, and employees.

On April 28, 2020, Supreme Court quickly convened a COVID-19 Task Force to address the myriad of issues raised by the public health crisis. Four assigned committees, respectively, addressed in detail (1) staffing, (2) facilities and equipment, (3) resumption of in-person, nonjury proceedings, and (4) resumption of jury trials. The comprehensive report directed each county’s local court leaders to submit a COVID-19 mitigation plan for approval. Every plan had to incorporate the Task Force’s findings and recommendations.

The May 1, 2020 Chief Judge Directive Regarding Temporary Measures outlined the creation of a local Recovery Plan Committee. It also delineated specific court operations per court division. The entire directive focused on the mitigation of risk and public health. It explicitly suspended all Milwaukee County jury trials until June 15, 2020.

Chief Judge Mary Triggiano’s Milwaukee County Recovery Plan, approved by the Supreme Court, outlined a phase-in approach. Successive “Phase” orders were issued in June, July, August, and September 2020 and specifying the slow but steady resumption of brick and mortar-based proceedings. The Plan began with select in-person hearings, in six criminal courts and one juvenile detention center courtroom.

Eventually, the system partners and the public health advisor agreed, with all caution, to a return to jury trials. The third floor of the courthouse was renovated to safely accommodate 100 jurors. Milwaukee County increased the number of jury summonses by hundreds per day, anticipating fallout in and hesitancy of juror attendance. Special protocols and social distance spacing were addressed in reassuring cover letters, surveys, and in abbreviating otherwise lengthy jury management presentations.

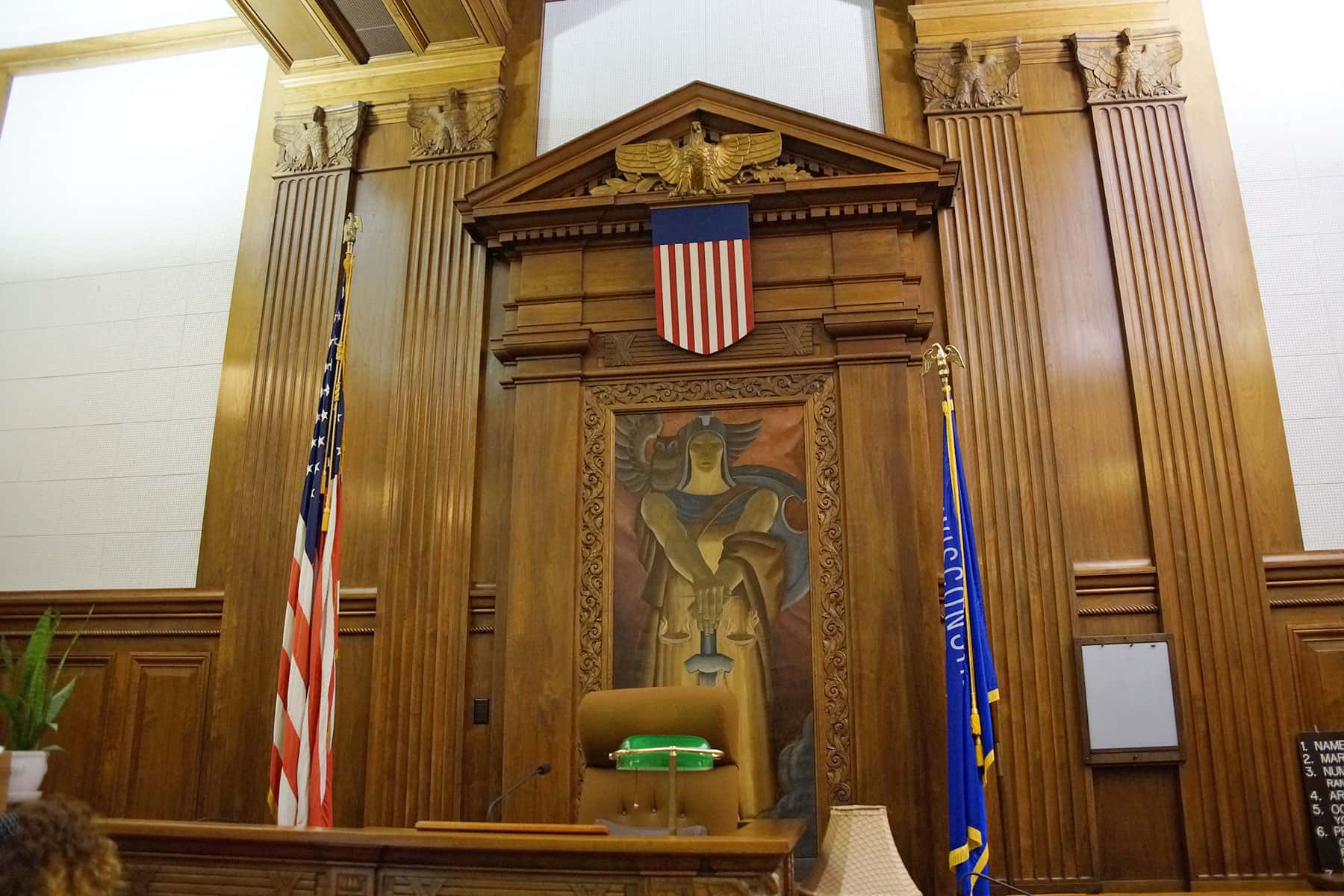

The Zoofari Convention Center at the Milwaukee County Zoo was refashioned as the site for the Children’s Court jury trials. All other jury trials were held downtown in “suites” of three courtrooms – to accommodate social distancing and to engender confidence of public health measures for potential jurors. The “suites” consisted of the largest courtrooms with one designated for jury selection, another for the actual trial, and the third for jury deliberations. At the outset, only two such suites were in place and therefore were shared by the criminal, probate, civil, and family court judges. Gradually more “suites” were created, expanding trial capacity. Eventually specific courtrooms were ordered opened for additional nonjury, in-person hearings. Jury trials began in July 2020. Fifteen months later, verdicts had been read in over 180 jury trials.

Courthouse leadership used a variety of methods to keep people informed about the ever-evolving public health issues and their impact on the courts. Town halls with the defense bar, directives, meetings, nearly daily newsletters from the County, emails, and countless meetings strategizing through the countless twists and turns that arose in the legal process. For example, Zoom hearings provided serviceable court access – if one had a smartphone or laptop, and a zoom account. For the many litigants without the necessary technology, “zoom rooms” at four library locations were created through a collaboration between the court and the Milwaukee Public Library.

The Recovery Plan Phases were adjusted based on surges in the various COVID-19 public health markers and in the responses to them. For example, upon declaration of the federal eviction moratorium, the judges created a whole new case management process to manage the flood of new Small Claim Court filings. After the U.S. Congress declared a six-month extension of the moratorium, in turn, the temporary protocols were further tweaked. As courtrooms could be reopened, facilities management would recombobulate them, with furniture that had been removed for social distancing and with the installation of any additional plexiglass. Despite the January 2022 COVID-19 variant surge, all court personnel who had not previously returned to the courthouse did so on January 3, 2022. Most scheduled hearings continued to be held by Zoom; newly scheduled hearings more likely than not will be held in person.

Recently, the County stopped COVID health screenings at the Courthouse entryway. In March 2022, the County issued adjustments to its two-year mask protocols. Now masks must be worn in the court facilities but only in public places, elevators, and when directly providing services to persons.

Discussions about the continued use of Zoom will persist. Each type of case must be evaluated by the pros and cons of remote appearances by litigants and witnesses. Technological advances, Constitutional interpretations, and ever-evolving practice and procedural norms have shaped the administration of justice throughout history. Likewise, in the present, expect changes in the justice system’s administration in a post-pandemic era.

© Photo

Lee Matz