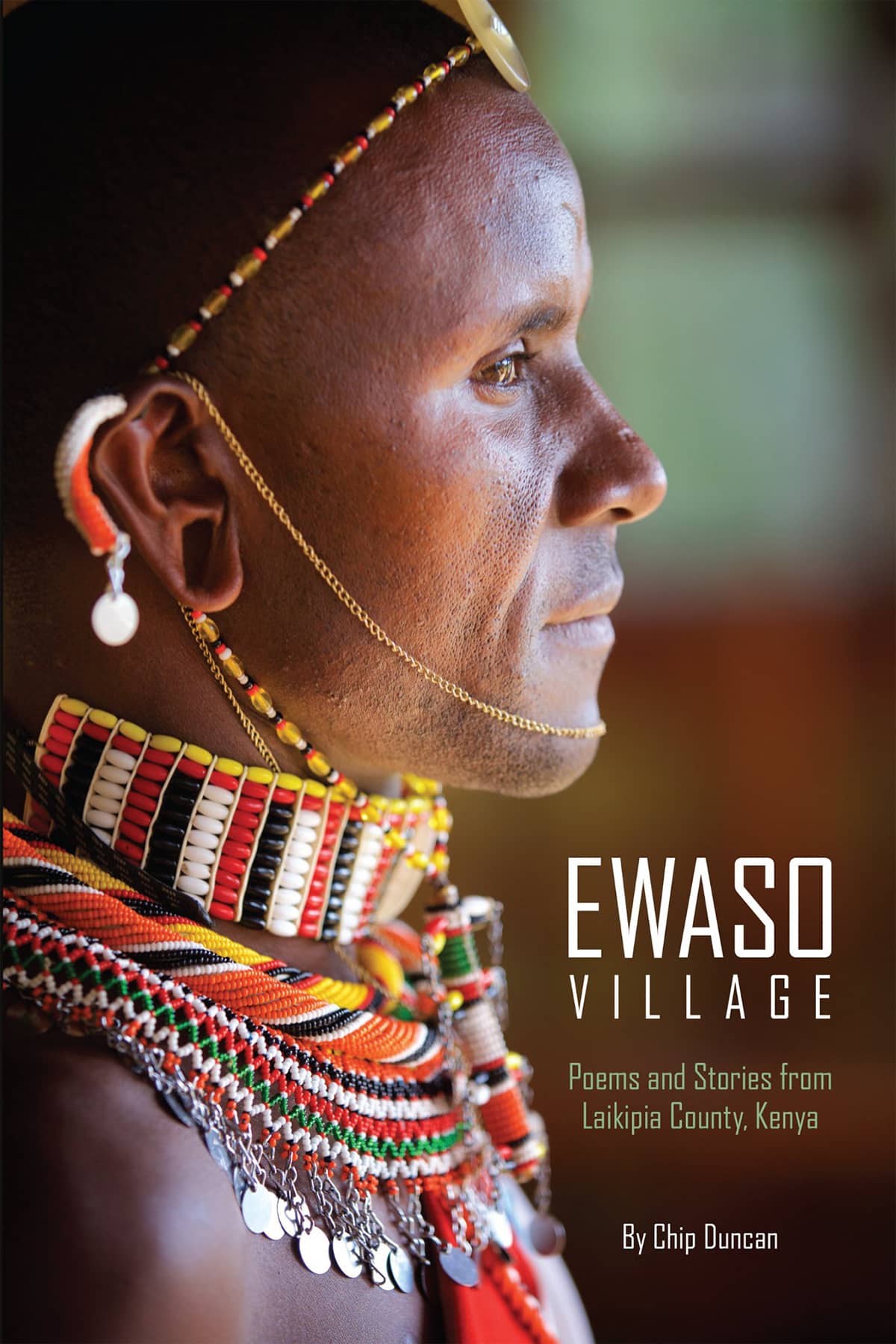

Milwaukee-based filmmaker, photojournalist, writer, and poet Chip Duncan shares a profound journey to Kenya in his new book, “Ewaso Village: Poems and Stories.”

Duncan’s work has taken him to distant ice fields, war zones, slums, shipyards, palaces, deserts, rainforests, and farmlands to produce more than fifty non-fiction films for international broadcast. Located in Kenya’s Laikipia County, Ewaso Village is his first book of poetry, and the first in a trilogy featuring indigenous cultures from around the world.

“Ewaso Village is luxurious storytelling for all of the literary senses: stunning photography, vulnerable prose and vivid poems. The collection is eloquent and frank, braiding culture and commentary. justice and joy, imagery and intimate impact. The collection of these pieces traveled me not as a vapid tourist. but as a human.” – Dasha Kelly Hamilton, Wisconsin Poet Laureate and Rubinger Fellow

This interview was conducted by Kenichi Sugihara.

Q&A with Chip Duncan

Kenichi Sugihara: Your work as a writer and filmmaker puts great emphasis on people and place. Why did you choose to take readers to this extraordinary landscape in a part of the world that’s relatively unknown?

Chip Duncan: I’m especially drawn to people … but place plays such a big role in what defines who we are and how we live our lives. I was born in Iowa, and from what my friends tell me, I can’t shake Iowa. I do visit Iowa often and I still love rolling corn fields and big blue skies filled with cumulous clouds. As much as I love my time in New York City and my home near Lake Michigan, some part of me is still drawn to small towns and rural life style.

Kenichi Sugihara: So you must feel right at home in Laikipia County then – it’s rural, relatively flat, big skies, people living off the land …

Chip Duncan: Ha, well, you have a point, but wow, these two places couldn’t be more different. The characters featured in Ewaso Village live in a savannah that has become a very difficult place to live. For centuries, the Maasai and their Samburu neighbors have lived as nomads while herding cows and goats in search of food and water. Water is plentiful in Iowa and the land is fertile. But climate change has made life near Ewaso Village a huge and, I believe, an ultimately insurmountable challenge. Lifestyles and traditions near Ewaso Village are changing because the resources that once made this area rich and diverse are no longer providing. What was once a 30-year drought cycle is now a 1 to 2 year drought cycle. The water table under the local river has depleted as the glaciers atop Mt. Kenya disappear. In more than a dozen visits to the village throughout every season, I’ve only the river running full one time. Literally, just once.

Kenichi: It doesn’t sound sustainable.

Chip Duncan: These are ingenious, innovative people so anything is possible, but challenges that began with the colonization of Kenya have only increased. What was once a free range is now a land with borders, fences, power lines and roads. Wildlife faces similar challenges, but wildlife has more advocates. Conservationists often have clout that the indigenous people rarely have, and the big safari ranches – the same ranches that were once possessed by the colonists – they also have financial resources and connections to the federal government. Most safari guides in this area are Maasai men who were raised in the bush … but if asked, they will also tell you how difficult it has become to sustain their family’s lifestyle and traditions. There may be a spring fed water source on the ranch feeding zebra, lions and elephants, but the local Maasai and Samburu herders aren’t allowed to use it to feed their cattle and goats.

Kenichi Sugihara: So that’s what Ewaso Village is about then – the challenges facing indigenous people in rural Kenya?

Chip Duncan: Not exactly, but I’m glad you asked. Ewaso Village is a celebration of a culture many of us know little to nothing about beyond the image of a Maasai Warrior in the film “Out of Africa.” But the book is a bit like yin-yang. There is no joy without pain, no happiness without sorrow. So while I use poetry to help articulate the story of the people I know and love in Ewaso Village, I also use prose to describe the “how and why” of the lifestyle, culture, and rituals that define their life in the early 21st century. I love this community and I hope that love comes through the book.

Kenichi Sugihara: Can you give me an example?

Chip Duncan: Let’s take death rituals. In the U.S. and Europe, even if we’re not religious, we tend to follow Judeo-Christian traditions when it comes to disposing of the body when someone dies. But that’s not at all the case near Ewaso Village. So rather than judge their practices, I try to find the beauty and purpose in their traditions. I’m a curious person so I want to know “why” things are the way they are. And if you go back to our discussion of place, how does “place” help define what they do with the body when someone dies? Here in the US, we usually burn or we bury. But many in the Ewaso community have a beautiful ritual that involves using goat fat, cowhide and, well, I don’t want to spoil it for you, but the poem Water, Earth, Sky is a great example. And by the time people are done reading it, I hope they’ll appreciate that their practices are not just unique, they’re also practical and a beautiful way to celebrate life, death, and place.

Kenichi Sugihara: You also use photography throughout this book. How do your pictures enhance the storytelling?

Chip Duncan: For a long time in my career, people referred to me as a documentary filmmaker. It was true, but around 2004 I started building still photos into my work abroad. I still remember a trip to Afghanistan where I brought along an SLR and wow, I could shoot vertical images for the first time! So like any good cinematographer, I started turning the camera sideways and voila, portraits instead of landscapes! Then, as a book writer, publishers like Select Books began asking me to include my still photos along with my stories. So today, I just call myself a “storyteller” and use whatever media I have at my disposal that helps create the best story. In Ewaso Village, readers can meet real people who are friends of mine, Maasai and Samburu elders, safari guides, cooks, teachers, herders, nurses … these are real people, thoughtful people, smart people, fun people who love to laugh, mothers, fathers, children … and in many cases, you can see their picture as well. I don’t just describe their dress, I show it. I don’t just talk about a lion eating a zebra, I show it. I don’t just write about a musical instrument, I show it. Maybe that’s part of what sets Ewaso Village apart from other books, I don’t know, but I do believe it makes reading the book an entertaining experience.

Kenichi Sugihara: You put a great deal of emphasis on the role of women in the Ewaso community. Can you explain that?

Chip Duncan: An entire chapter and most of the afterword are dedicated to a group called the Chui Mamas. In English they’re called “Leopard Women.” The Chui Mamas group was co-founded by a local Maasai woman named Ellie and I try to share her inspiring story in the book. What started as a handful of single, mostly older women sitting and beading together under an acacia tree has become an organization of more than 450 women who are united in their quest for better educational opportunities, better jobs and more choices for girls as they enter marriage and child bearing years. This is not a passive group. I see the Chui Mamas as one of the finest examples in the world of women empowering women, women fighting for the rights of women, and women making a difference. I won’t share all the details here, but yes, if you’re looking for success stories, the Chui Mamas are among them.

Kenichi Sugihara: Besides telling a part of their story, are there other ways you’re involved with the people in this region? I know you visit annually, but what else?

Chip Duncan: Even during the pandemic, I managed to make a visit to Ewaso Village. But clearly, the challenges they face are considerable. The pandemic ruined tourism in that region. When I was there during the late summer of ’21, it had been eighteen months since the local lodge had had a foreign visitor. When I returned in March of this year, the situation hadn’t changed. Without jobs and with their worst drought in years, food is scarce. Because I serve on the board of a small not-for-profit that helps provide resources in this area, we were able to assist. Since October of 2020, we’ve delivered more than 40 tons of food, and as we’re talking, we have another food drive in the works before year’s end. Colleagues of mine in Nairobi documented the first food relief effort which included Kenya Red Cross. And the board I serve with is called the Loisaba Community Conservation Foundation. LCCF does take contributions and there is no overhead at all – 100% of the donations go straight to the people in Ewaso Village. My personal quest is to increase support for the Chui Mamas and donations can be made to LCCF specifically for their work in the community.

Kenichi Sugihara: You also include a foreword by a Kenyan journalist, why?

Chip Duncan: Salim Amin isn’t just any journalist. Salim has been recognized globally for his work and he’s in the heart of a career that has made him a household name in Nairobi. His legacy also includes his father’s, photojournalist Mohamed “Mo” Amin. I was introduced to Mo’s work more than two decades ago, and I see some of myself in Mo’s work. He died in ’96, but Mo’s story is captivating in part because of his willingness to go where others won’t go and to tell stories that are often forgotten by the big networks and publishers. Mo was comfortable with the Maasai. He was comfortable in Somalia and Pakistan, Rwanda or documenting the Hajj. He worked well in wilderness, found ways to navigate and survive crisis, and if measured fearlessness is a trait to admire – and I think it is – then Mo set the bar. His son, Salim, has built on Mo’s legacy so to have his foreword in the book Ewaso Village is a privilege.

Kenichi Sugihara: Where can people find your book?

Chip Duncan: Ewaso Village is available in print by order through any bookstore, or it can easily purchased on Amazon or similar online services in print or e-version. This is also my first book featured on Audible and, because it includes poetry, it is read by yours truly.