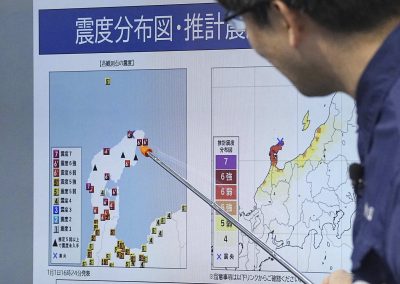

The powerful earthquake that shattered the peace of New Year’s Day in central Japan did not spur massive tsunamis like those that scoured the Pacific coast in 2011, killing nearly 20,000 people and forcing tens of thousands of people from their homes.

The tsunamis that did roll in along the Sea of Japan, on Japan’s western coast, were mostly just a few feet high, rather than waves up to 15 feet tall predicted in alerts issued just after the magnitude 7.6 quake struck on January 1.

But the alarms and evacuation orders, and the dozens of strong quakes that came before and after the main quake on January 1, summoned memories of the triple disasters nearly 13 years ago. As of January 3, local officials said 73 people were confirmed killed in the quake that struck on the coast of the remote Noto peninsula, about 185 miles northwest of Tokyo.

Searchers were combing through rubble, a task lent urgency by forecasts for heavy rain that could trigger more landslides and collapses, racing against the clock to find survivors. Some were buried in landslides or trapped in houses whose roofs collapsed. Firefighters were using power saws to access people trapped in a small, 7-floor apartment building that fell sideways off its foundation.

“Hardly any homes are standing. They’re either partially or totally destroyed,” said Masuhiro Izumiya, the mayor of Suzu city, which suffered heavy damage.

Two days after the quake, a man watched silently, wiping his eyes with a towel, as rescuers pulled his wife’s body from beneath their collapsed home.

The quake struck on the one day of the year that nearly all Japanese take off: The New Year holiday is the country’s biggest festival, when families gather to sit in heated “kotatsu” tables, eat “osechi” delicacies and rice cakes, and just take it easy.

The calm was vanquished by TV announcers who urgently and repeatedly warned people in areas that might be flooded to seek higher ground, without delay.

Tens of thousands of people living in areas near where the quake struck sought shelter in government buildings and schools as authorities warned against returning to buildings possibly weakened by dozens of strong aftershocks.

Others lined up patiently to get drinking water from tanker trucks sent in to help tide residents over until broken pipes could be fixed.

“It’s flattened my house so we can’t get inside. So I’m here with my wife sleeping together in a huddle while talking to others and encouraging each other. That’s the situation now.” said Yasuo Kobatake, who was visiting his hometown in Suzu when quake occurred.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and other officials sternly warned against posting misleading or “malicious” information online after some people posted videos of the gigantic 2011 tsunami as if it was from the January 1 quake.

The disaster was an inauspicious start for 2024. According to Asian astrology, it is a Dragon Year that usually would bring good luck and prosperity. So far, it has brought a quake on January 1 and a fiery landing of a Japan Airlines plane in Tokyo on January 2, after a Japan Airlines flight from the northern island of Hokkaido crashed into a smaller Japan Coast Guard aircraft on the runway. All 379 passengers and crew of the JAL plane escaped. Five people perished on the smaller plane, which had been preparing to deliver relief supplies for quake victims.

The holiday’s celebrations turned somber: Kishida postponed plans for a ceremonial New Year visit to the Ise Shrine. Public visits to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo for New Year greetings by the Imperial family were canceled as Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako conveyed their sympathies to victims of the disaster.

The damage is much smaller in scale than in 2011, but still catastrophic.

The Noto area is renowned for old, picturesque wooden-frame homes and shops, often with heavy tile roofs that experts say are most vulnerable to the kind of violent shaking seen in the January 1 quake. Most, but not all, of Japan’s modern buildings are built to stronger, quake-resistant specifications, usually using reinforced concrete that tends to hold up well.

Much of the damage from the January 1 quake to more modern buildings appears to have resulted from landslides and subsidence, which severely damaged homes even 100 kilometers (60 miles) away in Kanazawa, the closest larger city.

Landslides and road collapses left some isolated communities cut off: Residents in Suzu used folding chairs, benches, and other things to spell out SOS in a parking lot — much as some distressed quake and tsunami survivors did in 2011.

The 2011 triple disasters along Japan’s northeastern coast began with a magnitude 9 earthquake offshore that was more than 125 times more powerful than this week’s quake in terms of the total energy it released, according to an online calculating tool of the U.S. Geological Survey. It unleashed tsunami with waves up to 40 meters (131 feet) high that pounded into the coast, across sea walls and up river valleys, wiping out entire communities in low-lying areas.

> READ: Revisiting the tsunami scars of Japan that still linger after more than a decade

It also triggered meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant that led to massive evacuations along the coast due to worries over radiation escaping from the disabled plant that have kept thousands from moving back.

The operator of the nuclear power plant closest to the epicenter of the January 1 quake, in Shika, said there were minor problems and damage, but nothing that would cause radiation leaks from the facility, where reactors were idled for safety checks.

Hokuriku Power apologized for quake-related power outages that affected 33,200 homes in the area — some of those who sought refuge said they were too cold without any heating due to the blackouts, with temperatures dipping near freezing overnight.

Further north, at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant in Niigata prefecture, the world’s largest atomic power plant by power capacity, the quake caused water to spill from fuel pools of two reactors. Its operator Tokyo Electric Power, which also is responsible for the wrecked Fukushima plant, said there was no damage or leaks.

TEPCO recently gained permission to restart the Niigata facility, which had been partially shut down at the time of the 2011 quake and has been undergoing safety improvements since that disaster, which did not affect it.

In February 2021, Milwaukee Independent photojournalist Lee Matz wrote about his treadmill exercise routine during the COVID-19 pandemic, while watching VideoWalks from Japan. He reflected on his experiences in the aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which struck while he had been living there.

That tragedy was what displaced Matz from Japan, returning him to America as a refugee. Twelve years later, Matz would be embedded with the Turkish Red Crescent, Türk Kizilay, reporting about the massive earthquake that decimated Türkiye and Syria on February 6, 2023.

> READ: Earthquake Mission in Türkiye: Documenting the devastation with Türk Kizilay