In the quiet morning light that graces the shores of Onagawa in Miyagi Prefecture, a small coastal town with a soul weighed down by history, 67-year-old Yasuo Takamatsu prepared for another dive into the cold embrace of the sea.

It has been a ritual he has repeated hundreds of times since 2013. A quest not for treasure, but for a piece of his heart lost to the depths on that fateful day in March 2011, when the earth shook and the ocean swallowed large swaths of Japan’s northeastern coast.

THE DAY THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

March 11, 2011, is etched into the collective memory of the Japanese people as a day of catastrophic loss. For Takamatsu, it marks the last day he heard from his wife, Yuko, who was 47.

She was swept away by the towering tsunami waves while at her office at the Onagawa branch of 77 Bank. The magnitude 9.0 earthquake, one of the strongest ever recorded, unleashed a tsunami of such ferocity that it obliterated towns and took the lives of thousands, leaving a wound in the nation’s spirit that has yet to fully heal.

A MESSAGE LOST IN THE WAVES

In the chaos of the disaster, Yuko managed to send a hauntingly simple email to Takamatsu: “Are you OK? I want to go home.”

Those were the last words Takamatsu would ever receive from her. They were words filled with love, concern, and a longing for safety that would never be fulfilled.

Someone found Yuko’s phone in the parking lot a month after the tsunami, not far from where she had vanished. Takamatsu found an unsent text on the pink flip phone. It was written at 3:25.

“So much tsunami,” it read. From that Takamatsu knew she was alive until 3:25, guessing that by then the tsunami was up to her feet on the bank’s roof.

Yuko is among the 2,523 people whose bodies were never recovered after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Search operations, now considerably smaller, have been ongoing over the past 13 years.

Miyagi Prefecture has the largest number of missing people at 1,213, with the remains of 47 people yet to be identified. Families like Takamatsu’s have been left in a perpetual state of waiting and wondering.

FIRST MEETING

Takamatsu met Yuko in 1988, when Yuko was 25 and an employee at the 77 Bank in Onagawa. He was a soldier in Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force. They fell in love right away. Takamatsu liked her smile, her modesty, and described her as gentle.

LAST MEETING

It snowed on the day of the tsunami, which was a Friday. Takamatsu drove Yuko to the bank located on Onagawa’s waterfront. He then drove his mother-in-law to the hospital in Ishinomaki. Takamatsu was on his way out the door when the massive earthquake hit.

He remembered that the entire world shook for a full six minutes. Takamatsu made his way back to Onagawa on old farming roads and listened to the radio for news of a tsunami. He received news that his son was safe at the University of Sendai, but he could not reach his daughter at school in Ishinomaki. Nor had he heard from Yuko.

A FATAL DECISION

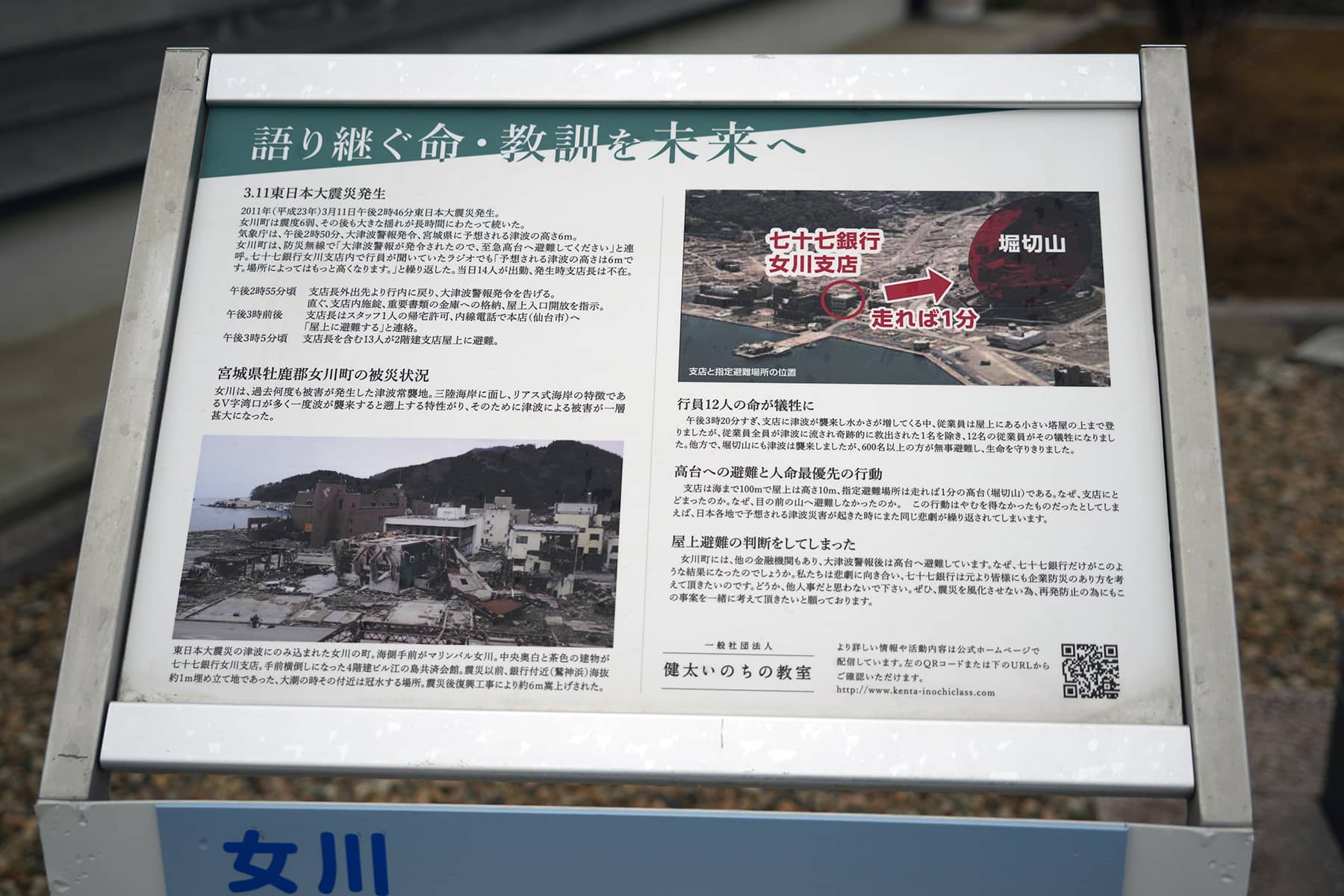

The 77 Bank Onagawa branch’s manager received a tsunami warning that only predicted a 20-foot-high wave. He gave the order to evacuate to the rooftop of their building, which was 32 feet high. But the tsunami hit the branch with a much higher than expected wave, estimated at between 49 and 57 feet. It washed away 12 of the 13 employees, including Yuko.

“To save your life, you must go to higher ground.”

The Onagawa Plaza of Life was created for the families of the disaster victims. On its monument, the words read:

“Thirteen bank employees fled to the roof of a two-story branch building. About 30 minutes later, the tsunami reached the roof, killing 12 people and leaving 8 people missing. There was a hill called Mt. Horikiri that could be reached in one minute by running, so why was the evacuation order given to the rooftop instead of the hill in front of us? The basic rule for tsunami evacuation is to go to higher ground. I wanted the bank to just say, ‘Escape to the mountains.’ How scary it must have been. How frustrating it must have been. How sad it must have been. How regretful it must have been.”

A VOW TO BRING HER HOME

Driven by the memory of Yuko’s last message, Takamatsu made a vow that has since defined his life. Having retired from the Ground Self-Defense Force, he began working as a bus driver. But he searched for his wife in every free moment.

He ultimately took up scuba diving to look for Yuko in the vast and murky waters where he believes she rests. He has descended into the ocean more than 600 times. Each one was a challenge, but Takamatsu remained driven by the slim hope of finding his wife, of bringing her home, and of fulfilling a silent promise he made to her.

A JOURNEY OF HEARTACHE AND HOPE

With each dive, Takamatsu braved not only the physical challenges of the deep but also the emotional turmoil of facing his loss over and over again. The ocean, with its eerie tranquility, held vast secrets and sorrows in its depths. Takamatsu has combed the ocean floor for any sign of Yuko, or others who are missing.

He has only found the remnants of lives once lived, like photo albums and clothes. But of Yuko, there has been no trace.

HEALING A COMMUNITY’S HEART

The scars left by the tsunami are not just etched into the landscape of towns like Onagawa, but also into the hearts of its people. Takamatsu’s personal odyssey reflects the broader struggle for healing and closure.

“The recovery of people’s hearts … will take time,” Takamatsu once said, acknowledging the complex journey of grief and recovery that many, like him, are still navigating.

A TALE OF UNYIELDING LOVE

Takamatsu’s story is about a man who refuses to give up on his wife, holding onto the faint hope that somewhere beneath the waves, he might find her and bring her home. His search continues, regardless of how elusive any closure may be.

As Takamatsu prepared for another dive, adjusting his diving mask against the chill of the March morning in 2024, he carried not just the weight of his own loss but the collective pain of a community still piecing itself back together.

One day Takamatsu, and Onagawa, will end the elusive quest for peace in the aftermath of tragedy. But not today.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz

Yasuo Takamatsu and Eugene Hoshiko (AP)

3.11 Exploring Fukushima: The Tōhoku region of Japan experienced one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded when a powerful earthquake was followed by a massive tsunami, and triggered an unprecedented nuclear crisis in 2011. With a personal connection to the tragedies, Milwaukee Independent returned for the first time in 13 years to attend events commemorating the March 11 anniversary. The purpose of the journalism project included interviews with survivors about their challenges over the past decade, reviews of rebuilt cities that had been washed away by the ocean, and visits to newly opened areas that had been left barren by radiation. This special editorial series offers a detailed look at a situation that will continue to have a daily global impact for generations. mkeind.com/exploringfukushima