At age 92, Dick Cavalco Sr. has experiences that span back to the Great Depression, World War II, and the Korean War. A local resident for the past four decades, he sat down with Milwaukee Independent to talk about a lifetime full of lessons. It was also the first time in 70 years that Cavalco had spoken in such detail about his service in Korea during the war.

Born and raised in Evanston, an Illinois community near the shores of Lake Michigan, Cavalco grew up enjoying his summers close to the water. It provided him with moments of joy and comfort, and escape from the era’s harsh realities.

“It was the 1930s and everyone was struggling from the Great Depression. Our family was fortunate to maintain a semblance of stability,” said Cavalco. “My dad endured a lot of hardship to ensure that we could get all the food, clothing, and security we needed.”

A pivotal figure in Cavalco’s young life was his mother, Inga, who was a natural leader in the family. He recalled how her Norwegian roots and charismatic personality left an indelible mark on him and his younger brother.

“My grandpa was born in Oslo, Norway, and my grandmother in Racine. So we always had a strong connection to Wisconsin,” said Cavalco. “Everyone in our neighborhood adored her. My friends often came over after school to visit her, even before heading to their own homes. They were drawn by her warmth and wisdom.”

Cavalco attended an all-boys Catholic high school, which played a crucial role in his formative years. The Christian Brothers – Midwest District is a religious community inspired by St. John Baptist de La Salle and dedicated to educational programs. Cavalco said they went beyond teaching and were mentors who shaped his character and instilled a deep sense of duty and responsibility in him.

“The Christian Brothers at St. George made a tremendous impact on me. They taught us to plan for the future and seek guidance from God. They treated us like children at first but gradually gave us more responsibility,” said Cavalco.

The guidance was essential for helping him transition into adolescence and face the challenges ahead. That greeted him in the form of Pearl Harbor. The Saturday morning cartoons that Cavalco would watch in his local theater were abruptly replaced. Instead, newsreels documenting conditions at the frontlines were projected on the big screen. The segments featured graphic footage from the war.

“Those newsreels showed tanks, planes, and every kind of war machine blowing up something, or being blown up in battle. The sheer scale of death, destruction, and the number of wounded was horrifying at times to watch,” said Cavalco.

Cavalco remembered watching segments of soldiers walking through buildings, going flow by floor and room by room. They never knew what they might encounter, whether it was a booby trap or an enemy soldier. He could not fathom how those men endured such dangers for three or four years.

“When the news shifted from Europe to the South Pacific, we saw the big guns pounding the islands. The Japanese soldiers were deeply entrenched, making it incredibly difficult to dislodge them. Watching the troops land, face heavy casualties as they tried to get off the beaches and into the jungle, and deal with the brutal conditions, it was all so shocking,” said Cavalco. “Some of the footage was quite graphic, but they showed it anyway.”

While World War II was a conflict that consumed the nation and Cavalco’s time attending movies, in his day-to-day life it was still an abstract matter. He was too young to understand how it impacted his environment, and it was a long way from home.

There was also a more pressing problem that required all of his attention, because it took place in his home.

“My young years were influenced by my mother’s illness when I was about 12 or 13. I took over the household responsibilities, which made me grow up faster,” said Cavalco.

During high school, he worked various summer jobs to help support his family, but mostly with the Cook County Forest Preserve. The job brought him into close contact with veterans who had fought in the Pacific just a few years earlier, exposing him to firsthand accounts. That presented him again with the brutal realities of war.

“I worked with many World War II veterans who shared their experiences with me,” said Cavalco. “Those stories had a profound impact on me, especially the ones by two Marine gunners who served in the South Pacific. They didn’t go into all the details. But when they talked about how the Marines took control of the islands and discovered what the Japanese had done to their captured buddies, it was chilling. That brutality led to a shift in their approach to taking prisoners. They just stopped taking prisoners.”

Cavalco had one startling experience while working in the forest preserve, when he found a body. The war newsreels had shown a lot of death, but only in the black and white of film. This was in color and in real life.

One of his older co-workers, a World War II veteran, became physically ill after seeing it. The incident gave Cavalco a glimpse into the long-term emotional and psychological toll of war, and the lingering trauma many veterans carried with them after the fighting had ceased.

Cavalco had planned to attend West Point after high school, applying in 1949 with a scheduled start in July 1950. However, North Korea launched its surprise invasion of the South in June 1950. After registering with the Selective Service, he ended up attending Northwestern University’s School of Engineering.

“I was focused on studying at the start of the Korean War. There was not much information available from the government or news media about the situation there. Everyone I knew, myself included, was largely unaware of the severity of the conflict in Korea,” said Cavalco. “Sometime later a few of my friends, who had been enlisted in the Army, Navy, or Marines, returned home in the summer and fall of 1952. When they shared their experiences, it was the first time in two years that I had heard such things. It was appalling to realize how little the American public knew about what was happening there.”

Soon after, Cavalco received notice from the U.S. Army that he had been drafted for the Korean War.

“I wanted to be a ‘service’ guy and defend my country. My mother’s family had a strong military tradition. One uncle was a Colonel in the South Pacific during World War II. He was in charge of the only African American unit sent overseas at that time, because the U.S. Army was still segregated then,” said Cavalco. “Another was an Admiral in charge of the Great Lakes Training Center. He was personally tasked by President Roosevelt to transition the facility from a peacetime to a wartime operation.”

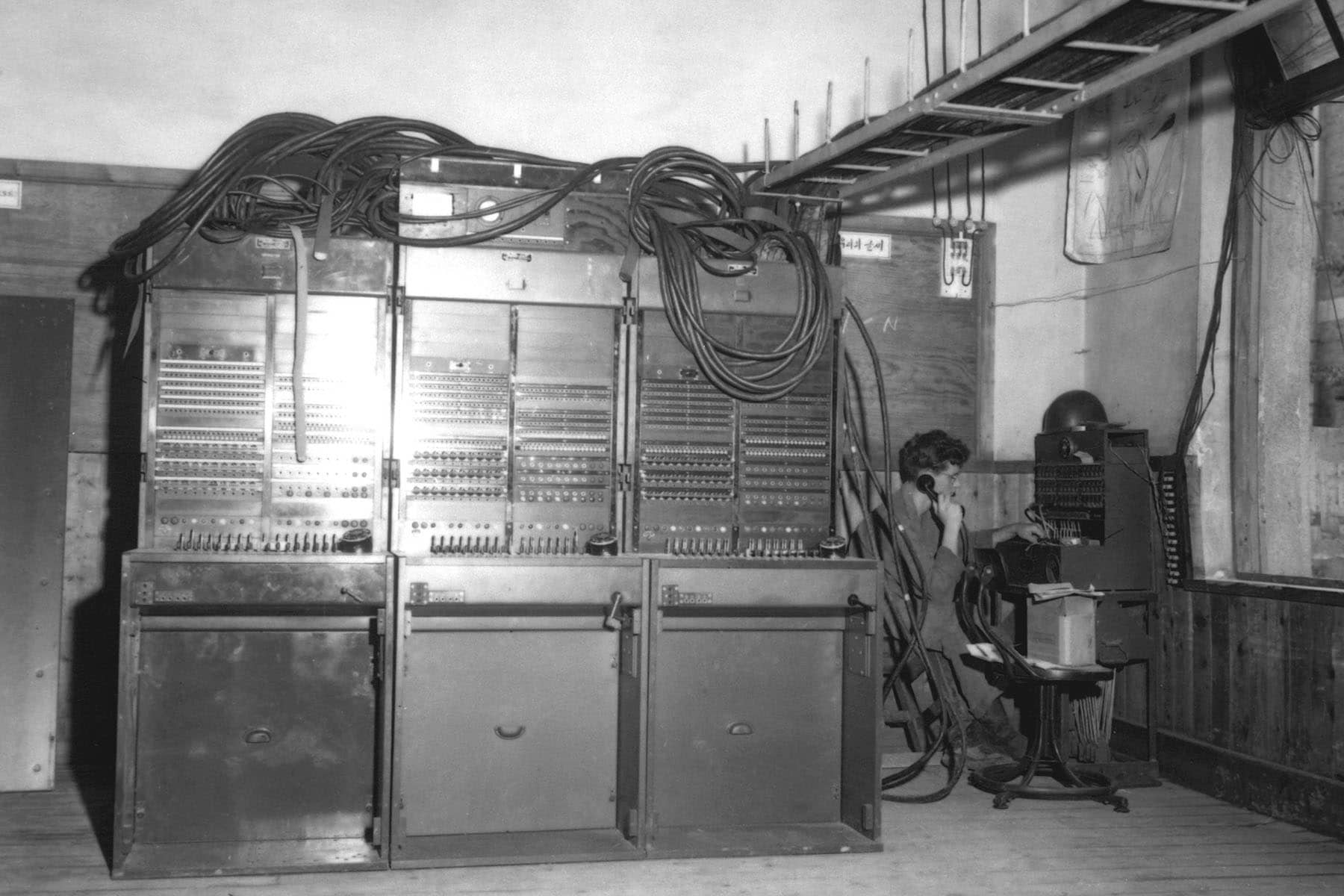

Being an engineering student, he was trained in communications and became a Wire Chief with the 304th Signal Battalion. Tasked with supervising a team of technicians and linemen, the Wire Chief was responsible for the critical installation and upkeep of telephone and telegraph systems.

“I found it fascinating because I did not know much about telephone exchanges, and it was intriguing to learn about them. We had three months of training, and I really enjoyed the new knowledge I gained,” Cavalco said.

The position required a deep understanding of signal equipment, including field telephones and switchboards, all of which were essential for transmitting vital messages in the heat of battle. The Wire Chief’s responsibilities extended to managing the security of the communication lines, safeguarding them against enemy interception or sabotage, and strictly adhering to military protocols. In addition, he would oversee the physical laying and repairing of wire and cable lines across the battlefront, and troubleshooting a host of technical issues.

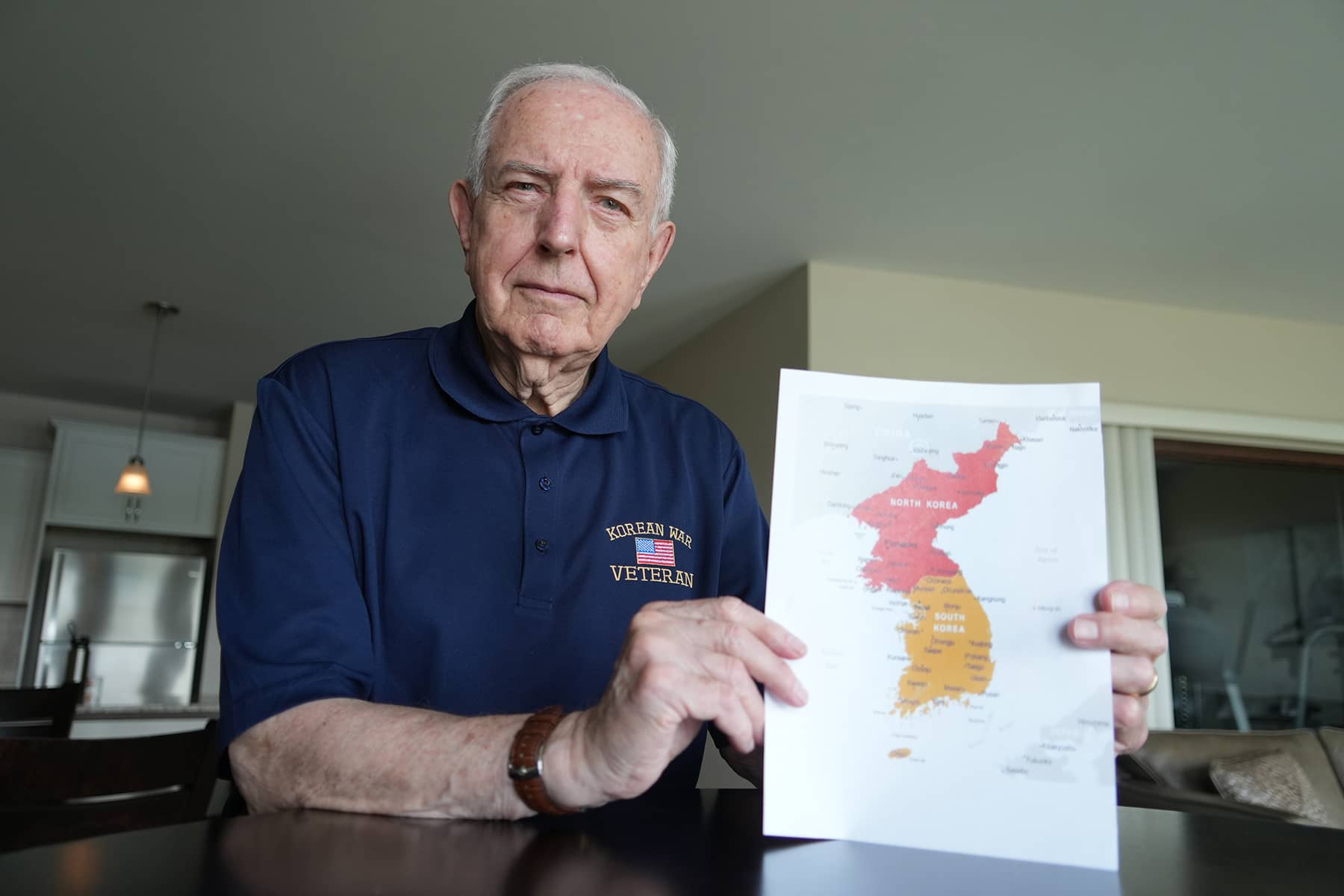

“So in 1952, at the age of 21, I was deployed to Korea. I shipped out from Fort Lewis, Washington, to Japan, and then to Korea,” Cavalco said. “My deployment came at a time when the Korean War was in full swing. We arrived near Inchon in the dead of winter, when the temperatures were freezing. It was a stark awakening. The tides at Inchon are some of the highest and lowest in the world, so we had a small window to get the ship close to shore and transfer to landing barges.”

As they prepared to disembark, several North Korean planes – relics from World War II, tried to bomb the ships in the harbor and strafe the shore. Cavalco raced off the beach and spent the night in a bombed-out shelter that did little to offer protection from bullets or the elements. The next morning he reported for duty at a position just north of Seoul, the capital city of South Korea.

The winter of 1952 in Korea was a harsh introduction to the realities of war for him. The conditions reminded Cavalco of his brother-in-law’s stories, who had fought at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in November and December of 1950.

For two years, United Nations forces had endured the harsh conditions of winter and summer in Korea. Cavalco said that spring and fall were very similar to Wisconsin’s weather. However, American troops were ill-prepared to be there from the very start.

“We did not have a clear plan until MacArthur arrived,” said Cavalco. “As a result, we lost a lot of men. And that was partly due to our poor maps. I was with the Signal Corps, and the maps often showed a distance of five miles between two points. But when we went to lay down telephone or communication lines, it turned out to be eight miles because of the difficult terrain.”

The landscape was rugged, with mountains and hills reaching from 4,000 up to 7,000 feet. They were not small hills, and the military was still not adequately prepared for such conditions.

“One of the first things the captain at the 304th headquarters told me was, ‘If you make a mistake, people die. You’re going to make mistakes, but don’t make them twice.’ It was a sobering realization, knowing that any error could cost lives,” said Cavalco. “The lack of proper supplies added to the challenges we faced, making the situation even more difficult.”

Cavalco had several noteworthy experiences during his tour in Korea, but one in particular stood out because it related to a broader historical context. Syngman Rhee was the first President of South Korea, serving from 1948 to 1960. Born in Korea in 1875, he became a prominent leader in the Korean independence movement during the Japanese occupation. Educated in the United States, he was the popular choice to lead the new government.

Both Rhee and the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, despite their differences, agreed on the unification of North and South Korea. The sticking point was about who would lead the new country, and under what style of government.

Rhee became increasingly frustrated with the ongoing peace talks and the division at the 38th Parallel. After a significant meeting with President Truman, tensions escalated. By May 1953, Rhee decided to further challenge the U.S. administration by organizing civilian riots in South Korean cities.

“At that time, I was stationed at the only telephone exchange in the area, responsible for its operations. On my way back from the exchange to the base, which was about seven or eight miles north of Seoul in a valley, we were instructed to avoid certain streets due to the demonstrations. Those demonstrations were intense, with men linking arms and moving in a slow formation. I was in a small truck with six other men. As we followed other trucks, we encountered a group of demonstrators who surrounded us and began shaking our truck violently. It was a terrifying situation, and I instructed everyone to prepare to defend themselves. Just as the situation seemed most dire, military trucks with 50-caliber machine guns arrived. They shouted warnings in Korean for the crowd to disperse or face consequences. Fortunately, the crowd broke up, and our truck stabilized,” said Cavalco. “After returning to our camp, just as I was about to sit down for lunch, an alarm went off indicating another threat. Our base was located about a mile and a half off of the main road, and from our vantage point, we saw a large group of possibly a couple thousand people approaching. The crowd included men, women, and children, some armed with knives and guns. Despite our warnings and even firing shots over their heads, they did not stop.”

Cavalco said that day was one of the lowest points he had experienced. It was chaos and the needless loss of civilian life that too often accompanied war. He also realized that while his experiences were challenging, they were nothing compared to what the soldiers on the front lines had to endure. They faced the true horrors of combat.

The last six months of his time in Korea were brutal. As part of Cavalco’s duties, he traveled to different units across the front to ensure communication lines were intact. Many were vulnerable to being cut by the enemy. The ability to communicate can mean the difference between life and death in war.

After returning home from Korea, Cavalco struggled with the emotional and psychological aftermath of his experiences in the military. Reintegrating into civilian life was a daunting task for some time. And like many veterans of previous wars, he found it difficult to talk about what he had seen and done.

“The memories of the war haunted me, and I struggled to adjust to civilian life. Fortunately, I had a strong support system, including a compassionate wife who helped me through my difficulties,” said Cavalco. “Her understanding and support were crucial in helping me cope with my trauma and begin to heal.”

Over time, Cavalco found ways to process his experiences and move forward. He continued to draw on the lessons he had learned early in life from his mother, the Christian Brothers, and the veterans he had served with.

But Cavalco did not talk about Korea for another 65 years. He said it felt pointless at the time and just let go of the idea to discuss it. There was so much information that had been withheld from the American people, and no independent platform could reach them with the technology of the time. The public was told that America was involved in a “police action,” like it was merely directing traffic.

“For years, there was a group of us and our wives, we would get together for great parties but nobody ever brought up Korea. The only time it came up was when my brother-in-law, who was a Marine from the outset in 1950, was asked a question,” said Cavalco. “It was the only time I heard about how he was part of the American forces originally driven all the way down into Pusan when the North invaded. Then he fought all the way back up into North Korea in the winter. He faced a horrific ordeal, walking over 600 miles under constant fire from the North Koreans. Then the Chinese entered the war and he went through a brutal winter retreat. He ended up hospitalized in Japan for three months with hepatitis.”

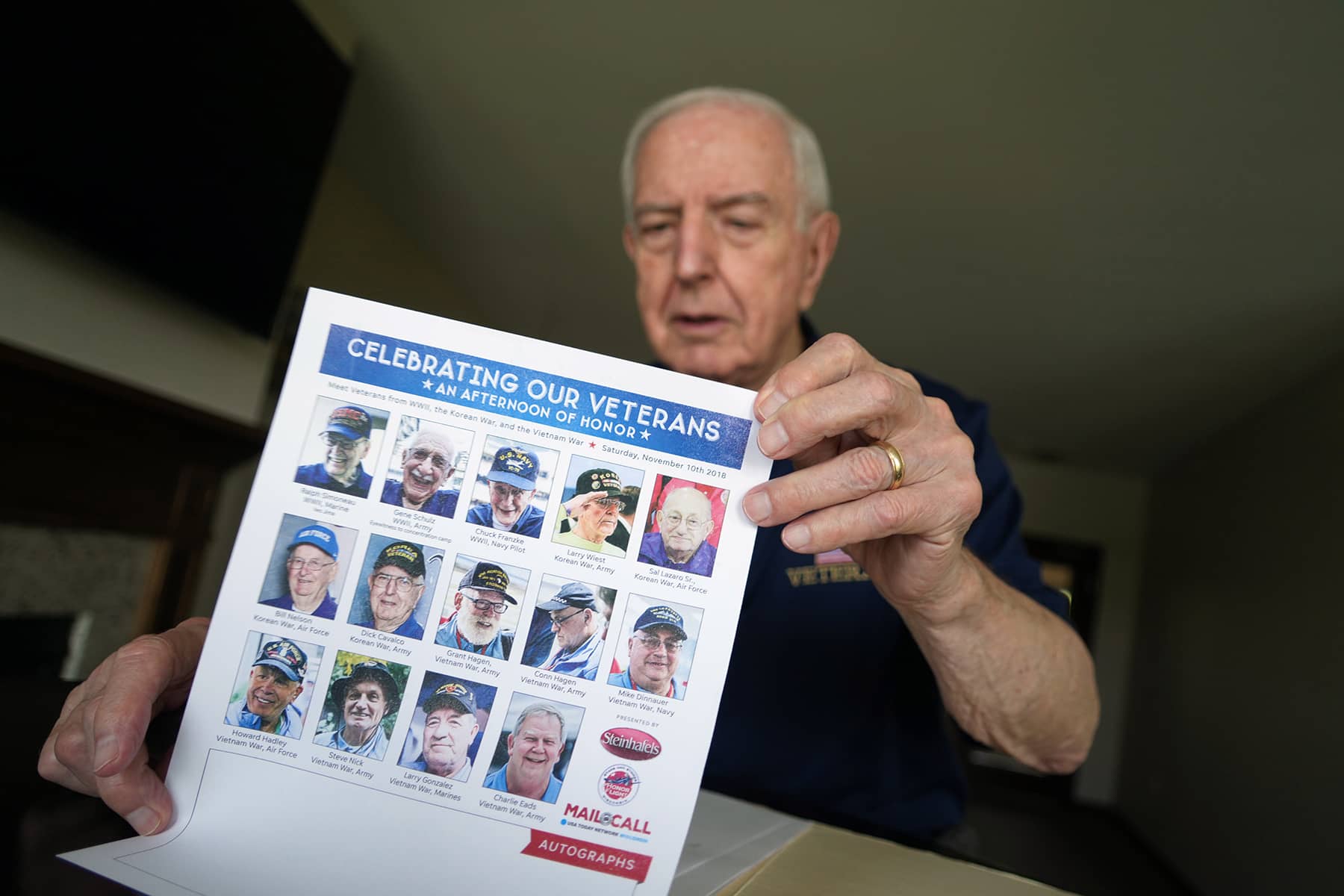

After he joined an Honor Flight in 2017, he decided that it was time to open up about the past. Stars and Stripes Honor Flight is a nonprofit organization that thanks veterans for their service by flying them to Washington DC, to visit memorials dedicated to their sacrifices. It began primarily to support World War II, the Korean War, and terminally ill veterans, providing the trips at no cost.

Participating in the Honor Flight gave Cavalco a sense of validation and appreciation that he had not experienced before. The recognition that he and his fellow veterans received during the trip, including the emotional encounters at the memorials and welcome ceremonies, provided a long-overdue acknowledgment.

“To withhold talking about the Korean War any longer would have been a disservice to everyone who I served with. The more I could share, the more people could understand, the more I could help honor their sacrifices,” said Cavalco. “This is not a pleasant subject to go over and rehash. But I could not have done it until I went on the Honor Flight. It took 65 years.”

Cavalco said he remembered living through it all, the monsoons, the flooded roads, the freezing winters. His regret was that he and other Korean War veterans did not talk about their service until recently, and now there were only a few of that generation left.

“We had training, but nothing prepared us for the true nature of war. And nothing since has taught us how to talk about such terrible things,” said Cavalco. “How can I fully explain what it was like? The cold, the relentless rain, and the tough conditions? That was just the background for the war. We endured it all, and that is something we always carry with us.”

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora