Milwaukee has been a home for many generations of various ethnic communities. However, a well-documented presence that continues to be recognized is Milwaukee’s German heritage.

There has been a wave of interest in recent years to uncover and uplift diverse voices from Milwaukee’s bygone eras. The efforts by enthusiasts and historians have sought to preserve those past stories as a way to understand how the early city was formed, and the social influences that led to what Milwaukee is today. This has included revisiting the generational contributions surrounding Black, Hispanic, and even Asian communities, especially Hmong.

However, one community that continues to be a focus of discussion, partly because of its strong and enduring cultural influence on Milwaukee is the German community. Milwaukee’s relationship with the German immigrant community has been so strong that it was once even called “the German Athens of America.”

While much research and documentation has already been published about Germans in the city, a personable perspective that compiled stories from the lives of ordinary people has been lacking a strong representation.

Anthropologists Jill Florence Lackey and Rick Petrie decided to shine a light on that lacking perspective of German voices. With their upcoming book, Germans in Milwaukee: A Neighborhood History, the authors attempt to collectively outline the various aspects of German influence on Milwaukee, particularly, through an impressive collection of over 1,200 interviews that focus on the influence of Milwaukee’s neighborhoods.

The appeal of the book’s approach is the impressive knowledge and collaborative effort that created the foundation for it to be written. Lackey and Petrie have more than twenty years of experience in studying Milwaukee’s neighborhoods and ethnic groups – with the added goal of taking anthropology out of classroom and academic settings and instead work within local communities.

The Milwaukee neighborhoods they have been working with have presented a perspective of the “German presence in the city from the ground level” that has yet to be holistically evaluated.

The book itself is an easy read with short but dense sections that have an appeal to a history enthusiast who is drawn to dates, genealogical family outlines, and historical landmarks. In conjunction with the anthropological writing style also comes personal interviews that share accounts from surviving members of the German community, all integrated throughout the book.

Quotes from the 1,200 interviews offer insight into the intimate and personal perspectives of Milwaukee’s German ancestry, its cultural attitudes, home life, values, and experiences that existed in the past but still reverberate influence to this day.

For instance, the book not only focuses on a particular building that served as a point for the German community, like Turner Hall or various cemeteries, but talks about unique aspects such as their leisure-time and nightlife.

Jones Island was an industrialized peninsula in Milwaukee that saw German families settle there. Many of the original immigrants came from a fishing village, and while the work was “strenuous, so were their leisure-time activities.” Here is an abbreviated excerpt from the oral interviews about this village:

* * *

THE POMERANIAN GERMANS OF JONES ISLAND

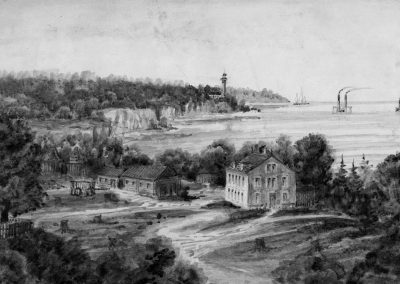

During the 1870s and 1880s, a small wave of Pomeranian fisherfolk found their way to the Milwaukee area and settled on Jones Island, a strip of land surrounded by Lake Michigan and two rivers.

JONES ISLAND: AN ISLAND THAT IS ANYTHING BUT

Today, the Jones Island peninsula on Lake Michigan is a Milwaukee neighborhood and is currently home to Milwaukee’s largest sewage treatment plant, warehouses, mountains of road salt, boxcars, railroad tracks, lift docks, petroleum tanks and a tiny park that commemorates the days when it was a fishing village.

But why is a peninsula called Jones Island? The name derives from a Captain James Monroe Jones, who built a shipyard on the peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. Over the years, the topography of the peninsula was altered by both human and natural forces. With a growth in commerce, lake vessels needed better access to Milwaukee’s rivers, hence the city of Milwaukee completed a “straight cut” across the peninsula, eliminating nearly a mile of river channel for most appreciative lake captains. The straight cut severed the peninsula’s connection to the mainland—hence came the designation “island.” However, within a decade, storm waves filled the island’s old river mouth with sand, and the island once again became a peninsula. But the name Jones Island persevered.

THE FISHING VILLAGE: “THE DAMNED DUCKS WOULD GET TRAPPED IN THE FISHNETS”

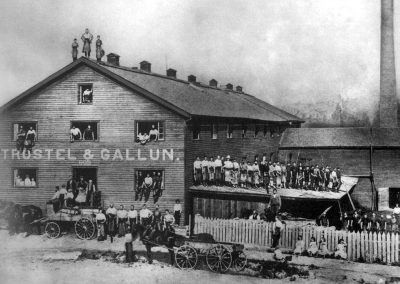

By the 1870s, a number of fisherfolk families from Europe had discovered the island was a fit place to earn their subsistence. These families included the Kaszubs from the Bay of Puck and the Hel Peninsula on the Baltic Coast of Poland, a handful of Scandinavians and Pomeranian Germans.

Most of the Germans who settled on Jones Island came from the fishing village of Altdamm on the Dammscher See, five miles from Stettin and about two hundred miles south of the Hel Peninsula. These Pomeranians had struggled with subsistence for generations and, during the late nineteenth century, faced the additional pressures of the Industrial Revolution, lack of sanitation, rampant unemployment and housing shortages. By 1870, some German fishing families immigrated to America and Jones Island. Most arrived in the 1880s.

Life was not much easier on the island. As squatters, they were not eligible for Milwaukee city services. And since they arrived with very little money, many of the fishermen initially relied on rowboats for their livelihoods, using set lines of pond (pound) nets. In 2001, Urban Anthropology Inc. conducted an oral history of Jones Island and interviewed the surviving members of the fishing village and their children. Many commented on the conditions on the island.

There was much isolation. People on the island were self-supporting, independent from the mainland. There was one cop from the city assigned to the island. That was it. You had gas lanterns for light at night and on the street. No plumbing. The houses were built everywhere, helter-skelter. There were no addresses, no grid of streets.

You got up early, worked late, went by a compass everywhere. It was very dangerous on the waters. Many drowned. On the way back, you would clean the nets out of fish so seagulls wouldn’t follow you everywhere. When you came back, you had the reel for nets to let them dry. The kids’ pastime was repairing nets.

There was no transport. No streetcar or bus. You paid 10 cents to row across the river. There was one milkman that came to the island. You did your washing in the river; we used Fels-Naptha soap to get the dirt out. You had your own chickens and goats and ducks. The damn ducks would get trapped in the fishnets all the time. There was a baker shop and a grocery on the island, but most everything came from home. We made our own sausages and butter, sewed our own shoes. Our water came from Lake Michigan or the Milwaukee River.

It was very tribal, with the Germans and Kaszubs. The Kaszubs spoke their own dialect of Polish, which wasn’t understood by the mainland Poles. They went to St. Stan’s church on Mitchell on the mainland. The Germans spoke low German and went to St. Peter’s on Eighth and Scott.

But despite the difficult conditions, life in the fishing village was not without its charms.

VILLAGE LIFE: “LIKE THE WILD WEST”

While the islanders’ work and subsistence strategies were strenuous, so were their leisure-time activities. These included a baseball team, bonfires, dances, swimming, a German men’s singing club, bands, religious holidays and a most robust tavern life. Informants from the oral history project described the nightlife.

There was a lot of drinking. Lots of taverns on the island. Dances every weekend. Fights broke out pretty often, and there were no police to stop them. That was common. It was a rough time, and they [islanders] worked hard and figured it was earned.

We all loved to drink and have fun. Every weekend, there were dances, and people would come from the mainland for the drinking and dancing and fish fries. The village had the reputation of being like the Wild West.

Just to ensure that the nightlife didn’t overcome the day life, the islanders had their own forms of social controls. Their beliefs in supernatural forces extended beyond their Christian faith. Families consulted crystal balls and Ouija boards for guidance. Two women on the island were branded witches and were said to have powers to lay curses on anyone stepping outside the locally imposed boundaries.

* * *

The book’s extensive interviews and personal stories are woven within the context of historical facts. The unique combination shows the intricacy of emotions, lifestyles, and influence that the German community experienced and passed along to future generations of Milwaukee. Being able to see the depths of a multifaceted Milwaukee will hopefully come about as more collections and historical books like Germans in Milwaukee: A Neighborhood History are published. Often such opportunities are driven by economic interests. But no ethnic legacy was forged in a vacuum, and it remains to the benefit of Milwaukee’s population to understand and fully recognize the extent of cultural influence from all the communities that have made the city their home over the past 175 years.

Kristen Leer

Reprinted from “Germans in Milwaukee: A Neighborhood History” by Jill Florence Lackey & Rick Petrie

(History Press 2021)

Germans in Milwaukee: A Neighborhood History – The History Press (April 26, 2021) 224 pages

Dr. Lackey, having taught anthropology at Marquette University for twelve years, was the founder of Urban Anthropology Inc., where she continues to serve as principal investigator in charge of research. Having earned a doctorate in urban cultural anthropology, she is the author of thirteen books, including Ethnic Practices in the Twenty-First Century: The Milwaukee Study, Strolling through Milwaukee’s Ethnic History, and Milwaukee’s Old South Side.

Rick Petrie is the executive director of Urban Anthropology Inc. He has a certificate degree in applied anthropology and a BA in art from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and has worked as part of the administrative staff for a variety of Milwaukee museums, including the Charles Allis Museum, Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum and the Old South Side Settlement Museum. He currently is on the staff of the Milwaukee County Historical Society and is the coauthor of Strolling through Milwaukee’s Ethnic History.