In 2023, a South Korean court made headlines by ordering Holt Children’s Services, the country’s largest adoption agency, to pay 100 million won, roughly $74,700, in damages to Adam Crapser, a 48-year-old Korean adoptee.

Crapser’s adoption story, marred by abuse, legal troubles, and eventual deportation, reflected the systemic failures and aggressive practices of South Korea’s adoption industry during the 1970s and 1980s.

The landmark case has brought to light the harsh realities faced by many adoptees from South Korea, and underscores the urgent need for justice and reform.

Adam Crapser’s journey began in 1979 when he was adopted by American parents at the age of three. His adoption was handled by Holt Children’s Services, a prominent agency known for its aggressive child-gathering activities during South Korea’s foreign adoption boom.

Crapser’s early years in the United States were marked by severe abuse and neglect by two different sets of adoptive parents. His ordeal included physical and emotional abuse, abandonment, and multiple run-ins with the law. The traumatic experiences culminated in his deportation in 2016, after a background check triggered by a green card application revealed his lack of U.S. citizenship.

In a civil case that lasted more than four years, Crapser sued both Holt and the South Korean government for mishandling his adoption and failing to protect his rights. While the court recognized Holt’s wrongdoing, it dismissed claims against the government, much to the disappointment of Crapser’s legal team.

“The (government) knew that children procured for adoptions were not being (properly) protected, that their human rights were being violated — they should have done something about it, but they didn’t. … It seems that the court simply saw the government as a monitoring institution, and not as an actor that directly committed illegal acts,” said Kim Soo-jung, one of Crapser’s lawyers.

Despite the ruling, Crapser’s case set a precedent and inspired more adoptees to seek justice for the wrongs they endured.

In a broader context, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has taken significant steps to investigate the fraudulent practices surrounding international adoptions. In 2023, the commission expanded its inquiry to include 237 more cases of adoptees who suspect their origins were manipulated to facilitate adoptions to Europe and the United States.

The investigation represented the most extensive examination of South Korea’s adoption practices to date, involving adoptees from 11 countries, including Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the United States.

The commission’s investigation remains crucial in uncovering the truth behind the widespread falsification of records, where many adoptees were falsely registered as orphans or had their identities fabricated.

The mass exodus was largely driven by profit motives and facilitated by agencies with close ties to South Korea’s military dictatorships, which saw foreign adoptions as a means to manage population growth and improve economic growth.

In recent years, international awareness of the issues surrounding Korean adoptions has grown. Denmark and Sweden, for instance, have ceased facilitating adoptions from South Korea due to the revelations of falsified records and unethical practices.

Adam Crapser’s case was not an isolated incident. His story is part of a larger narrative involving thousands of Korean adoptees who have faced similar challenges. Approximately 200,000 South Koreans were adopted overseas over the past six decades, mostly to White families in the West.

Many of the adoptees, like Crapser, were subjected to abusive environments and legal vulnerabilities due to the negligence of both South Korean agencies and foreign adoptive parents.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 aimed to remedy some of the issues by granting automatic citizenship to adoptees under 18 at the time of the act’s passage. However, those adopted before 1983 were left in a precarious situation, vulnerable to deportation if they encountered legal troubles.

The issue of deportation has had devastating effects on many Korean adoptees. Prior to the Child Citizenship Act, adoptive parents were responsible for naturalizing their children before they turned 16. Many parents, unaware of the requirement, failed to do so, leaving their adopted children without legal citizenship.

The consequences of the oversight have been severe. Adoptees like Crapser, who found themselves entangled in the legal system, faced deportation despite having lived their entire lives in the United States. The case of Philip Clay, a Korean adoptee who was deported and later committed suicide in 2017, underscored the tragic outcomes of such deportations.

Adoptees deported to South Korea often struggle to adjust due to language barriers, lack of familial connections, and cultural dislocation. The Adoptee Rights Campaign estimates that 20% of adult Korean adoptees in the U.S. are at risk of deportation.

The Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2024 was introduced in the 118th Congress in June of 2024. If enacted, the legislation would grant U.S. citizenship to all individuals internationally adopted before the age of 18, regardless of current age, interactions with criminal legal systems, or deportation status.

Supporters of the bill, which has been proposed nearly every year since 2015, believe the legislation is crucial in preventing further injustices and ensuring that adoptees receive the protections they deserve.

The South Korean adoption scandals are not just a historical issue, but a present-day crisis that continues to impact the lives of many adoptees in America and around the world.

In September, a report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission finally revealed adoptions from the biggest facility for so-called vagrants, Brothers Home, which shipped children abroad as part of a huge, profit-seeking enterprise that exploited thousands of people trapped within the compound in the port city of Busan.

Thousands of children and adults — many of them grabbed off the streets — were enslaved in such facilities and often raped, beaten, or killed in the 1970s and 1980s.

The commission previously found the country’s past military governments responsible for atrocities committed at Brothers. Its latest report is focused on four similar facilities in the cities of Seoul and Daegu and the provinces of South Chungcheong and Gyeonggi. Like Brothers, these facilities were operated to accommodate government roundups aimed at beautifying the streets.

Ha Kum Chul, one of the commission’s investigators, said inmate records show at least 20 adoptions occurred from Daegu’s Huimangwon and South Chungcheong province’s Cheonseongwon in 1985 and 1986. South Korea sent more than 17,500 children abroad in those two years as its foreign adoption program peaked.

Ha said children taken from inmates at Huimangwon and Cheonseongwon were mostly newborns, who were transferred to two adoption agencies, Holt Children’s Services and Eastern Social Welfare Society, which placed them with families in the United States, Denmark, Norway and Australia. Most of the infants were transferred to the agencies on the day of their birth or the day after, Ha said, indicating that their adoptions were determined pre-birth.

While the facilities’ records say some of the women submitted memos expressing their consent to give away their children, other records indicate women were being pressured to do so, Ha said. A 1985 inmate record from Huimangwon flags a 42-year-old inmate with supposed mental health issues for “causing problems” by refusing to relinquish her child. Officials later note that she eventually did.

“It’s difficult to accurately determine how many more adopted children there might have been in other years,” Ha said, citing the commission’s limitations in staff. For Huimangwon, Ha said, the commission was only able to look through its inmate records from 1985 and 1986 and still found 14 adoptions. A further six adoptions were linked to inmates at Cheonseongwon.

At their peak, Huimangwon had about 1,400 inmates and Cheonseongwon 1,200. That was still smaller than the population at Brothers, which exceeded 3,000.

The commission has also been conducting a separate investigation into the cases of 367 Korean adoptees in Europe, the United States, and Australia, who suspect their biological origins were manipulated to facilitate their adoptions. It is expected to release an interim report on that later this year.

The commission also identified other human rights problems at the four facilities, which included Gaengsaengwon in Seoul and Seonghyewon in Gyeonggi province. The facilities’ death tolls were high — the 262 inmates who were reported as dead from Gaengsaengwon in 1980 accounted for more than 25% of the facility’s population that year, Ha said.

Nearly 120 bodies of Cheonseongwon inmates were provided to a local medical school for anatomy practice from 1982 to 1992, the commission said. Most of the bodies were transferred to the school on the day the inmates were declared dead or the day after, and there are no indications that the facility made efforts to transfer the bodies to relatives, according to the commission, which didn’t identify the school.

Huimangwon, Seonghyewon, and Cheonseongwon also regularly received inmates transferred from Brothers, suggesting a “revolving-door” labor-sharing scheme between facilities that likely increased profit and prolonged the inmates’ confinements, the commission said.

The population at South Korea’s vagrant facilities peaked in the 1980s as the then-military government intensified roundups to beautify streets ahead of the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympic Games held in Seoul. South Korea transitioned to a democracy in the late 1980s and has long stopped its practice of grabbing homeless people, the disabled and children off the streets and confining them.

Brothers closed in 1988, months after a prosecutor exposed its horrors. Seonghyewon now runs welfare programs for homeless people in the city of Hwaseong, while the three other facilities have changed their names and the services they provide. None of those facilities immediately released comments following the commission’s report.

“The four confinement facilities had been allowed to continue their operations without receiving any public investigations even after 1987,” when Brothers was exposed, said Lee Sang Hoon, one of the commission’s standing commissioners. “It’s significant that we have comprehensively revealed the details of the human rights violations at (other) vagrant facilities across the country that had been concealed for 37 years.”

MI Staff (Korea), with Kim Tong-Hyung

Kim Sung-min (AP), Jin Sung-chul (AP), Im Hwa-young (AP), Yonhap (via AP), Old Major, (via Shutterstock)

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

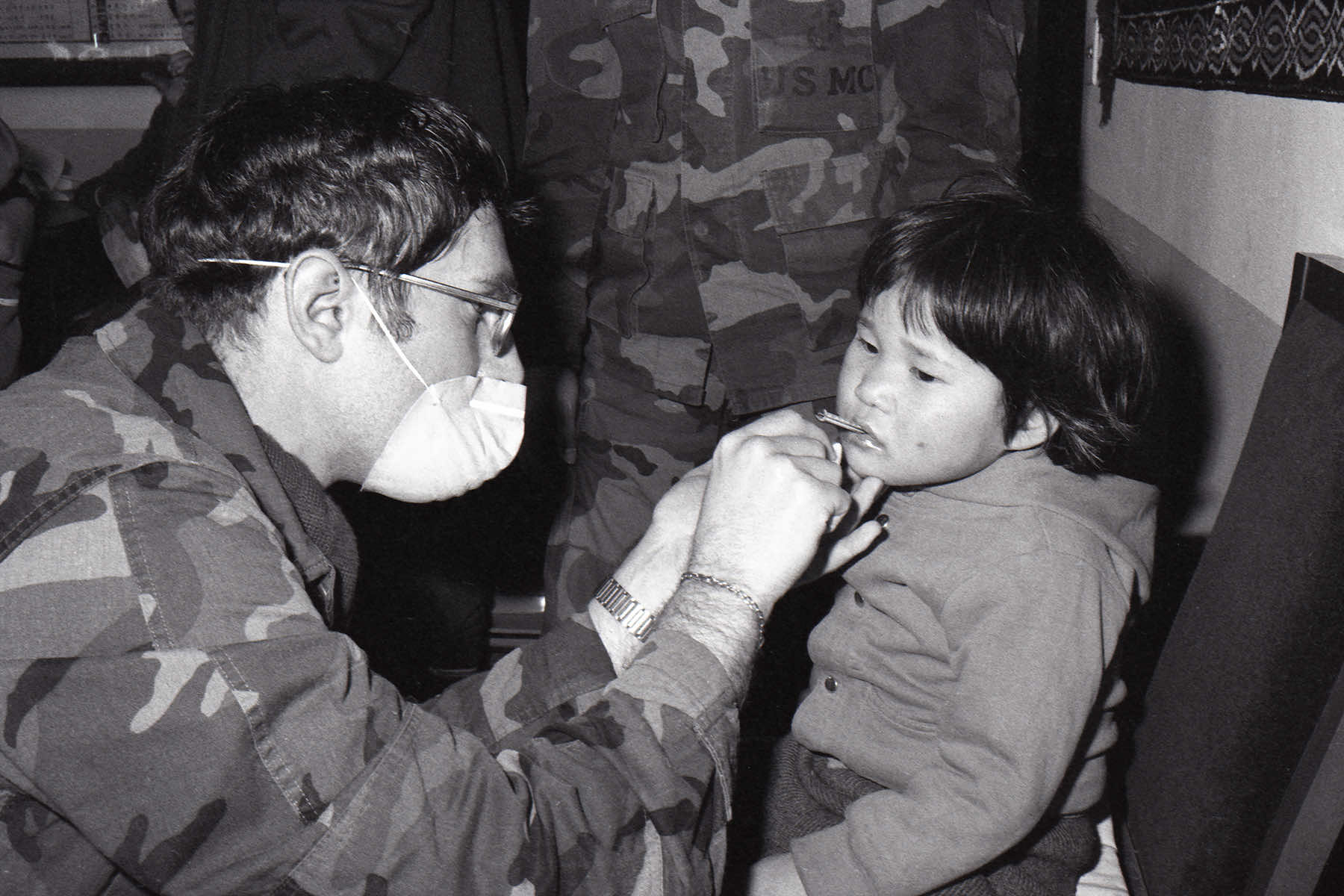

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora