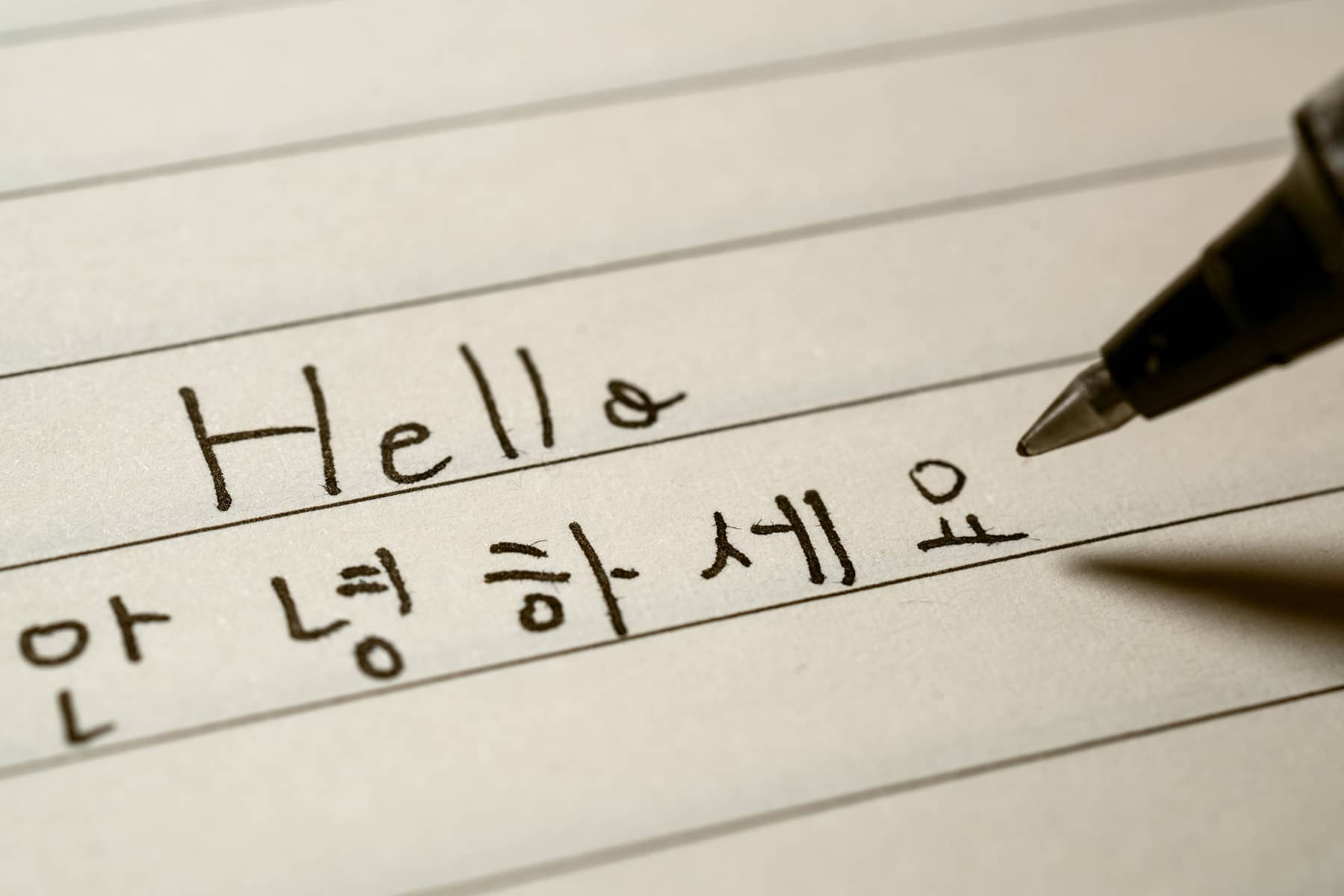

Few linguistic developments in history have been as profoundly impactful and meticulously crafted as the creation of Hangul, the Korean alphabet. Developed in the 15th century under the visionary leadership of King Sejong the Great, Hangul stands out for its simplicity, accessibility, and scientific foundation.

The 15th century in Korea was a period of significant cultural and intellectual activity. The Joseon Dynasty, which had established its rule in 1392, was keen on promoting Confucian ideals and advancing societal welfare.

Amidst that backdrop, King Sejong the Great ascended to the throne in 1418. Known for his wisdom and progressive outlook, the King’s reign is often considered the golden age of Korean culture and science.

One of King Sejong’s most enduring legacies is his commitment to improving the lives of his subjects. At the time, literacy in Korea was a privilege reserved for the elite, who were educated in Classical Chinese. The common people, who made up the majority of the population, found the complex Chinese characters difficult to learn and use.

Recognizing this barrier to literacy and effective communication, King Sejong embarked on an ambitious project to create a new and accessible writing system.

In 1443, King Sejong and a group of scholars from the Hall of Worthies (Jiphyeonjeon) began developing what would become Hangul. This group of scholars, known as the Hunminjeongeum Society, worked in secret, driven by a shared vision of linguistic democratization.

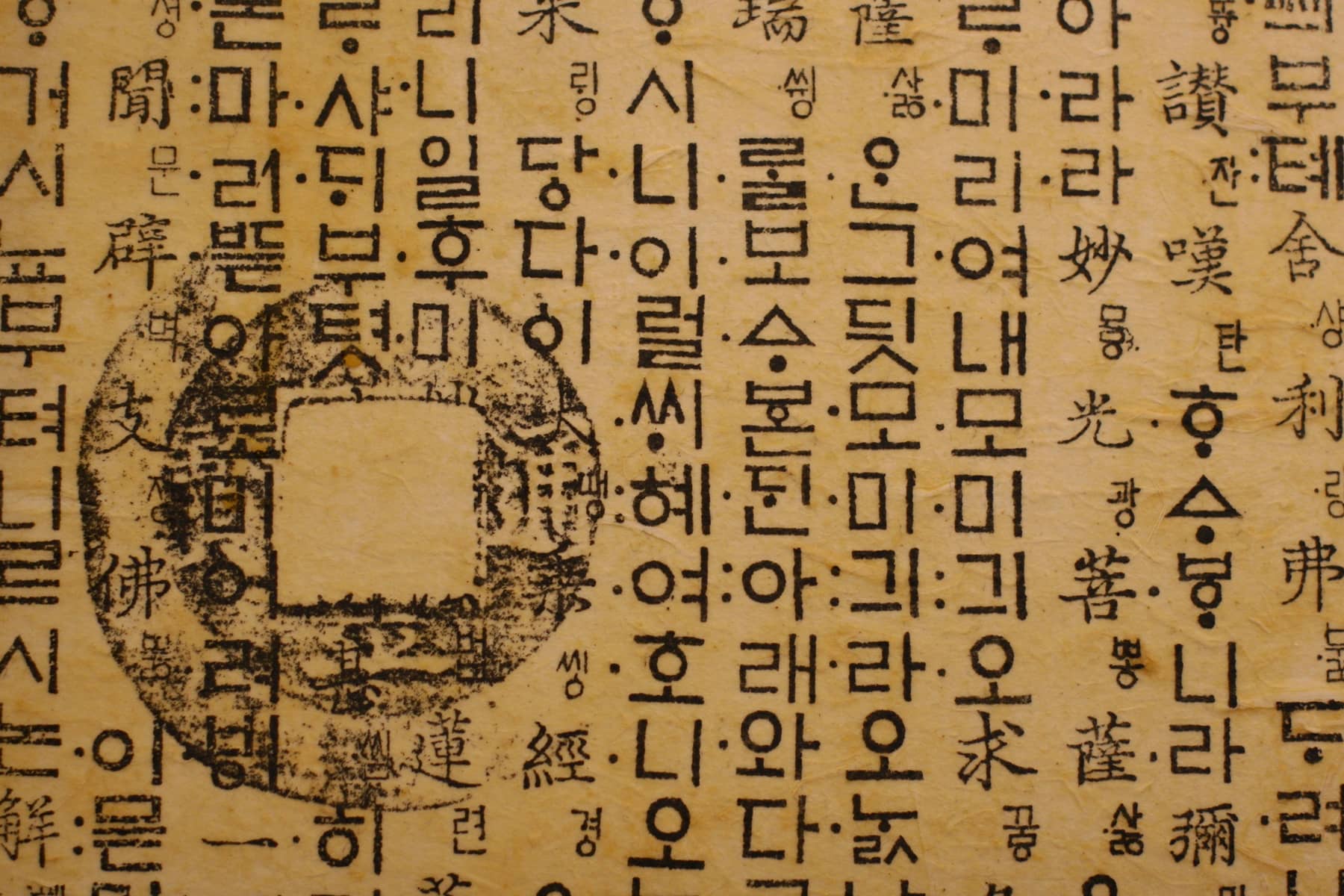

Their efforts culminated in the creation of a new alphabet, officially promulgated in 1446 through a document titled “Hunminjeongeum” (훈민정음), which translates to “The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People.”

The preface of the Hunminjeongeum Haerye, an explanatory text accompanying the original document, revealed King Sejong’s motivation:

“Because the speech of this country is different from that of China, it does not match the sounds of Chinese characters. Therefore, many among the ignorant people, being unable to communicate their thoughts, often cannot get their grievances off their chests. I am greatly distressed by this, and so I have newly designed twenty-eight letters, which I wish to have everyone practice at their ease and make convenient for their daily use.”

Hangul’s design is a testament to the ingenuity of its creators. Unlike many writing systems that evolved gradually over centuries, Hangul was intentionally and scientifically constructed to reflect the sounds of the Korean language. Its structure is both simple and sophisticated, enabling easy learning and efficient communication.

The consonants in Hangul were designed to mimic the shapes of the speech organs involved in their articulation. This phonetic symbolism is a core feature of Hangul’s innovative design. The basic consonants, known as Choseong (초성), are categorized into five groups based on their phonetic properties: velar, alveolar, labial, dental, and glottal. For instance:

ㄱ (g): Represents the shape of the back of the tongue touching the soft palate.

ㄴ (n): Resembles the shape of the tongue touching the upper gums.

ㅁ (m): Depicts the shape of the lips when producing the sound.

ㅅ (s): Reflects the shape of the teeth when producing the sound.

ㅇ (ng): Represents the shape of the throat.

These basic forms can be modified by adding strokes to represent related sounds. For example, the consonant “ㄷ” (d) is a modification of “ㄱ” (g), with an additional horizontal stroke indicating a different place of articulation.

The vowels in Hangul are equally remarkable, rooted in philosophical concepts and natural elements. The basic vowels, known as Jungseong (중성), are derived from three fundamental symbols:

Sky (•): A round dot or circle representing the heavens.

Earth (ㅡ): A horizontal line representing the flat earth.

Human (ㅣ): A vertical line representing a standing person.

These symbols can be combined in various ways to create different vowel sounds. For example:

ㅏ (a): Combination of the vertical line (ㅣ) and a dot (•) positioned to the right.

ㅓ (eo): Combination of the vertical line (ㅣ) and a dot (•) positioned to the left.

ㅗ (o): Combination of the horizontal line (ㅡ) and a dot (•) positioned above.

ㅜ (u): Combination of the horizontal line (ㅡ) and a dot (•) positioned below.

Hangul is written in syllabic blocks, with each block representing a single syllable. A typical syllabic block consists of an initial consonant (choseong), a medial vowel (jungseong), and sometimes a final consonant (jongseong). For example:

가 (ga): Combination of ㄱ (g) and ㅏ (a)

나 (na): Combination of ㄴ (n) and ㅏ (a)

사 (sa): Combination of ㅅ (s) and ㅏ (a)

This block structure allows for a compact and aesthetically pleasing script, facilitating both reading and writing.

Hangul’s design also reflects a deep understanding of phonology and morphology. The alphabet is versatile and capable of representing a wide range of sounds through combinations of basic symbols. The morphological flexibility also allows it to adapt to the evolving phonetic landscape of the Korean language.

The increased accessibility of written language led to a significant rise in literacy rates. Educational materials, literature, and legal documents were produced in Hangul, making information more widely available. This shift not only improved individual knowledge and empowerment but also contributed to the overall intellectual and cultural development of Korea.

Hangul also played a crucial role in preserving Korean culture and identity. During periods of foreign domination, such as the Japanese occupation (1910-1945), the use of Hangul became a symbol of resistance and national pride. Despite efforts to suppress the Korean language and culture, Hangul endured. Its existence and usage reinforced a sense of unity and resilience among Koreans.

However, the Korean language has more recently evolved in distinct ways, following the end of World War II and the peninsula’s division between North and South Korea. Political, social, and cultural differences between the two countries have influenced the development of their respective versions of Korean, leading to notable variations in vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, and usage.

VOCABULARY DIFFERENCES

One of the most noticeable differences between North and South Korean is the vocabulary. This divergence is driven by the differing political ideologies, cultural influences, and foreign language borrowings in each country.

Pure Korean Words: North Korea has pursued a policy of linguistic purification, known as “Juche” (self-reliance), which emphasizes the use of native Korean words over foreign borrowings. As a result, many Sino-Korean words and loanwords from other languages have been replaced with native Korean terms. For example, the word for “computer” in North Korea is “전자계산기” (jeonjagyesangi), which means “electronic calculator,” whereas in South Korea, the term “컴퓨터” (keompyuteo) is commonly used.

Ideological Terms: North Korean vocabulary includes many terms that reflect its political ideology and the cult of personality surrounding its leaders. Phrases and words related to socialism, communism, and Juche ideology are prevalent.

Foreign Borrowings: South Korea has been more open to adopting foreign words, especially from English, reflecting its globalized economy and cultural exchanges. This is evident in words like “핸드폰” (haendeupon) for “cell phone” and “인터넷” (inteonet) for “Internet.”

Modern Terms: South Korea’s rapid technological and cultural advancements have led to the creation and adoption of new terms that are often influenced by global trends.

PRONUNCIATION VARIATIONS

While the basic phonetic structure of Korean remains consistent, there are some differences in pronunciation between the North and South.

Consonant Sounds: North Korean pronunciation tends to be more conservative, retaining older pronunciations for some consonants. For instance, the consonant “ㄹ” (r/l) is pronounced more prominently in initial positions, whereas in South Korea, it is often softened or silent.

Vowel Sounds: There are minor differences in vowel pronunciation, though these are less pronounced than consonantal differences.

Intonation: South Korean intonation and speech patterns can be more varied, influenced by regional dialects and the fast-paced nature of modern Korean society.

GRAMMATICAL AND USAGE DIFFERENCES

Grammar and usage have also evolved differently in the two Koreas, although the core grammatical structures remain similar.

Formal Language: North Korea maintains a more formal and rigid use of language, reflective of its hierarchical and controlled society. Official documents and speeches often use older, more formal grammar structures.

Orthography: The North has made efforts to simplify Hangul spelling and grammar rules, aligning with its ideological focus on purity and self-reliance.

Colloquial Language: South Korean language usage is more dynamic, with a greater acceptance of colloquialisms, slang, and informal speech. This is partly due to the influence of media, pop culture, and the Internet.

Standard Language: The South has seen a standardization of its language around the Seoul dialect, influenced by its status as the capital and cultural hub.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES

The cultural and social contexts of North and South Korea have played significant roles in shaping their respective languages.

Isolation: North Korea’s isolationist policies have minimized foreign influence on the language, resulting in a more internally consistent linguistic evolution.

Propaganda: Language in North Korea is heavily influenced by state propaganda, with many terms and phrases designed to reinforce the regime’s ideology.

Globalization: South Korea’s open economy and cultural exchanges have led to a language that is more flexible and influenced by global trends.

Media and Technology: The widespread influence of K-pop, Korean dramas, and the Internet has introduced new vocabulary and expressions into everyday language.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

One of the most common racist slurs used by Americans is believed to be inadvertently derived from the Korean language. The term “Gook” in English is a derogatory reference to people of East and Southeast Asian descent. How the highly offensive word originated is unclear, as there are several theories.

One possibility comes from the Korean word “국” (guk), meaning “country.” Hanguk “한국” is how South Koreans refer to their nation. Miguk “미국” is the Korean name given to America, taken from the Mandarin meaning of “beautiful country.”

It is speculated that U.S. soldiers in the Korean War could have heard locals saying “miguk” (미국) in their reference to Americans, and misinterpreted it as Koreans introducing themselves as … “Me gook.”

When U.S. troops were stationed on the Korean Peninsula at the outbreak of the Korean War, so prevalent was the use of the word “gook” during the first few months of the hostilities that General Douglas MacArthur banned its use. He feared that Asians would become alienated from the United Nations Command because of the insult.

Despite MacArthur’s early prohibition, the term was nonetheless used by U.S. troops during the conflict, and U.S. postwar occupation troops in South Korea continued to call Koreans “gooks.”

A STANDARDIZED GLOBAL ALPHABET

While there is no widespread or officially recognized movement to make Hangul an international standard for writing languages, there is considerable global interest in doing so. Some linguists and cultural advocates promote Hangul as a potentially useful script for languages without a native writing system or for those seeking a more efficient script.

An example of that advocacy was seen at the “Alphabet Olympics,” where Hangul was praised for its efficiency and the potential for international applicability. In the 2009 contest, Hangul was evaluated against other scripts for its scientific design and ability to represent a wide range of sounds. Some participants expressed interest in adopting Hangul for their languages, especially in regions without established orthographies.

As South Korea continues to innovate and thrive, the legacy of Hangul remains a cornerstone of its cultural heritage, and the enduring power of language as a vehicle for progress.

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora