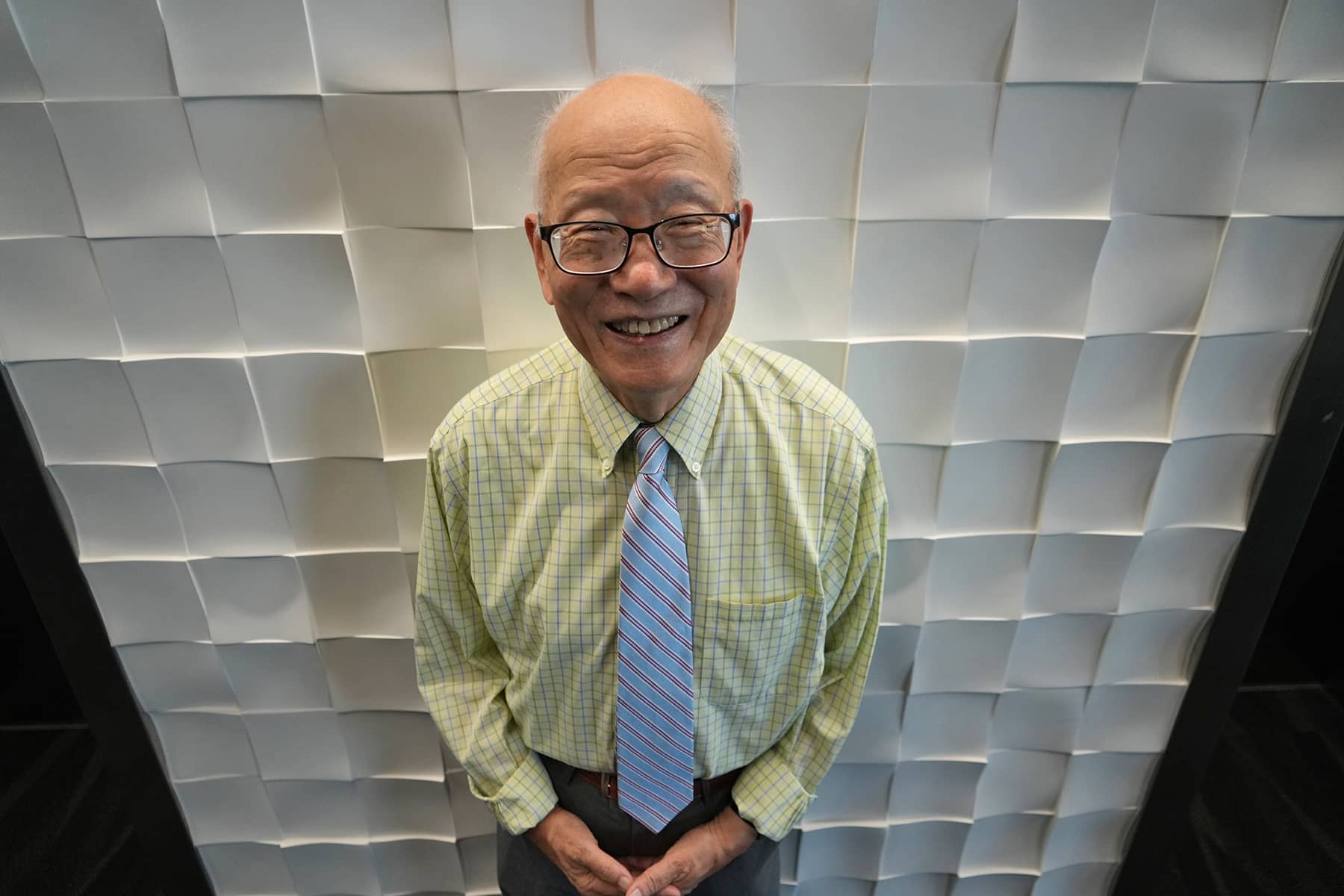

Born in 1941, Dr. Byung-il Choi MD witnessed cycles of turmoil in Seoul over the first few years of his young life. Those days were filled with curiosity about the foreigners he saw on the streets, and later the tanks that rolled into his neighborhood.

The earliest memories of Dr. Choi stretch back to a time when Korea was under Japanese colonial rule. It was a period of intense political and social upheaval that would also forge his lifelong yearning to care for others.

“I remember taking a train ride with my parents to my mom’s birthplace. It was a first-class train because it had mahogany wood interiors. That detail stuck with me because the interior had such a beautiful finish, and was so smooth to the touch,” said Choi. “Usually only the Japanese who could afford tickets for luxury trains. After Korea’s Independence in 1945, those luxury trains were destroyed, along with other Japanese symbols. Most regular trains either stopped running on time or stopped running entirely later when North Korea invaded. That’s how I know I had to be 4 years old, because it was still during the Japanese occupation.”

Choi was mostly oblivious to the measure of time in his childhood, being too young to match events with dates on a calendar. As he got older and reflected on his past, Choi was able to closely approximate many of his experiences against recorded history.

That was how he knew he was about 5 years old in 1946. That was when the cholera epidemic hit a turbulent Seoul. His mother took him by train to see a doctor for his condition, a serious case of diarrhea. His father was waiting for them at the train station, as his mother carried him on her back.

“What I remember about our Liberation Day was the crowds. Seoul had a streetcar and it was decorated with flowers. People were piled on it and cheering. Others also came out to celebrate and filled the streets, shouting “manse” (만세) which is a traditional Korean exclamation used to give a salute in celebration.”

Choi’s father was very much a self-made man. He aspired to become an official in the Korean government and prepared rigorously for the entry exams at a very young age. In those days, an individual had to pass an extremely competitive exam to qualify for such a position. It was a life-defining test, and Koreans were not encouraged to participate in the government structure that occupied their nation.

“Despite the challenges, my father eventually found work with the government. Unfortunately, it was under the Japanese administration. He wasn’t pro-Japanese. He was pro-humanity, without any political affiliations,” said Choi. “He continued to advance on his own merits, without any connections or favoritism, even earning the respect of the Japanese officials.”

When the U.S. took over control with a military government in 1945 at the end of World War II, Choi’s father became the first department chair of taxation for the city of Seoul. He was in his late 30s by the time Choi came along, already having a head full of gray hair like an old man.

“My father always believed in the goodness of people. He used to say that any good deed you do will eventually be rewarded, even if not immediately,” said Choi. “He was heavily influenced by Confucian ethics, which emphasized moral righteousness.”

Choi’s mother was also a significant influence on his formative years. She had not received a formal education growing up because there were no schools in the village where she was born. But she was a very wise and savvy person.

“While my father influenced me intellectually, my mother shaped me emotionally – even though at times I tried to distance myself from them,” said Choi. “She always told me, ‘Losing is winning,’ because if you win, you have to worry about someone taking revenge later. That idea has remained a guiding principle for me, that not every battle is worth winning.”

The months leading up to the Korean War were fraught with tension and violence, as the newly liberated and subsequently divided nation struggled to find its footing in the aftermath of Japanese rule.

Even as a small boy, Choi was aware that acts of brutality took place in the city, even near his home. Choi witnessed firsthand the early stages of political violence when a neighbor, a “nice looking young man” who was well-liked, was assassinated in a hail of bullets by Communist terrorists.

Having a front-row seat to the coming devastation at the tender age of 9, Choi had only to gaze out the window of his room to see external forces plunge his nation’s future, and his family’s prosperity, into uncertainty.

“When the Korean War broke out in 1950, everything changed overnight. Seoul was occupied by North Korean forces. My father was hunted by Communist terrorists for his position in the local government. He came home one day, beaten and bleeding,” said Choi. “Later our family was directly threatened when Communist soldiers raided our house, looking for my father. Thankfully, he wasn’t home at the time, so he escaped being captured. My mom knew that if the soldiers had found him, they would have shot him on the spot.”

On June 25, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) invaded South Korea, crossing the 38th parallel in a surprise attack that marked the start of the war. The capital of South Korea fell within three days. Choi saw the Russian-built tanks supplied by Stalin roll through his neighborhood.

The fate of his father, and many other uncertainties, hung over Choi and his family. Every day was a narrow escape from the chaos of war.

Choi’s life under North Korean occupation was a stark contrast to the relative stability of his earlier childhood under Japanese occupation. Schools were quickly transformed into tools of propaganda, as the Communist regime sought to indoctrinate young minds.

“I was just elected class president in the fourth grade when the Communist troops arrived. So when the war started – from my perspective as a child, it was a great disappointment that I couldn’t even enjoy that role,” said Choi. “On June 27, my school was abruptly closed and we were all sent home. We had no idea what was going to happen next, or if we would ever have classes again.”

The homes in his neighborhood had originally been built for the families of Japanese railway workers. As Imperial Japan expanded into Manchuria, or Manchukuo as it was known locally, it depended on railroad infrastructure. That part of Seoul was a freight train hub for logistical operations. It moved people into the colonial frontier and brought plundered materials out.

Choi attended Buksung Elementary School (서울북성초등학교) in Seoul, which was up the street from his home. It had been a private school for Japanese students from railway families, built during the early years of Japanese occupation. It even had its own Shinto shrine.

By the time Choi was old enough to attend classes there, World War II was over and the Japanese people had left. It was then a public school where anyone could attend.

When his school eventually reopened under the Communists, a few weeks after they started the war, it was a different world entirely. The school’s name had been changed to the Choson People’s Republic Elementary School. It foreshadowed the other drastic adjustments that followed.

“Characters that spelled the school’s new name were carved into a sign that was placed over the old name. Our curriculum had been replaced with books that glorified Kim Il-sung and the North Korean government,” said Choi. “There was no practical education taught at school, just brainwashing indoctrination that served us the state’s ideology. It was also disheartening to see our once-respected teachers becoming instruments of propaganda, teaching us to sing songs praising the new regime and even showing us how to draw the North Korean flag.”

Choi still carried the trauma of those lessons after so many decades. He could still draw a picture of the North Korean flag, and he could still sing the songs he was taught to praise Kim Il-sung. It was a chilling reminder of the long-lasting influence propaganda can have on children.

Despite the violence that roamed the streets of Seoul at all hours of the day and night, Choi also remembered moments of unexpected kindness from the most unlikely places.

“When the North Korean soldiers raided our home during their occupation, they took everything of value and all our food. My other stored months of rice and all those supplies were taken to feed the Communist army,” said Choi. “When asked by his comrades if there was rice stored in one of our barrels, he chose to lie by saying there was none – which left us something to eat. It was a small act of humanity in a time when such gestures were rare. My mother told me after that, even enemies had moments when they could show they had some goodness in their hearts.”

The war swept south but from Choi’s limited vantage point, he only knew what he saw with his own eyes or overhead in conversations between adults. Little news from outside of Seoul was able to circulate, or even within the city, because the North tightly controlled the flow of all news and information.

While he was oblivious to the North Korean push to Busan, it was evident that the war was becoming more desperate and intensified. Choi’s family faced increasingly difficult decisions to ensure their survival.

In July, Choi remembered watching American bombers appear over the skies of Seoul, dropping their massive payloads across the city, presumably on Communist positions. Fires would burn for hours, sending thick black pillars of smoke into the sky.

His mother decided to send him to her rural village for a little while, which was further away from the dangers of air raid strikes.

“My mother believed it was safer for me to stay with distant relatives where she was born, a town about 30 miles south of Seoul near the historic city of Suwon,” said Choi.

Best known for its UNESCO World Heritage site – the Hwaseong Fortress, Suwon gets attention in modern times for being the home of Samsung Electronics’ global headquarters.

“The journey was perilous, including crossing the Han River on a ferry because all the bridges had been destroyed,” said Choi. “That was around the area of Yeouido, which was just a sandy beach with an airstrip back then. Now it is where the Korean National Assembly Building stands.”

In some Korean families where an only child had no siblings, cousins of a similar age often filled that intimate role. Choi’s mother did not have brothers or sisters but considered her cousins that way. So it was her “cousin,” who Choi thought of as an uncle, who escorted him by bicycle to the countryside.

At one point in their travel along the road to Suwon, they were surrounded by a group of North Korean soldiers. Choi feared that his uncle would be taken to a labor camp.

“I didn’t know what to do, and in my fear, I started crying uncontrollably,” said Choi. “The North Korean soldiers noticed me crying, and my uncle pointed to me, saying, ‘Look at him, this is my nephew. He’s terrified. I have to take him home.’ He pleaded with them. Miraculously, they let us go.”

The moment reinforced his mother’s words, that there was some humanity even in those who were considered the enemy. After they managed to escape the close call, Choi continued to ride south with his uncle.

“Along the way, I saw North Korean soldiers transporting their supplies and weapons on ox-drawn carriages,” said Choi. “Eventually, we arrived at my mom’s village, and I started playing with my distant cousins. In the countryside, I lived like a farmer’s kid, far from the bombs and dangers in Seoul.”

The rural life provided Choi with a brief respite from the horrors of war. But the impact of the bloody conflict was everywhere. A road used as an important transport corridor was located near the village. Choi would often see a stream of refugees going in one direction and soldiers going in the other.

After spending several weeks in the countryside, the American bombing around Seoul had stopped. Choi’s family made the risky decision to bring him back. It was another arduous trek led by his uncle, but Choi was happy to reunite with his family.

“The city I returned to was a shadow of its former self, with much of it reduced to rubble by the relentless bombing campaigns. Yet, despite the devastation, there was a determination among the people to rebuild and carry on with their lives,” said Choi. “The artillery never hit my house, while striking so many others. It was really a miracle that my parents survived.”

About two weeks later, Choi would see an American for the first time. The U.S. soldier was riding atop an M26 Pershing tank that drove into his neighborhood. The 7th Infantry Division entered Seoul on September 25. Just three days later it recaptured the city.

A hilly area near his school not far away was the scene of a fierce battle. Choi’s side of the area had been spared, due to the direction of the attack. The homes and families on the other side were not as lucky.

“The first American soldier I saw had a big smile on his face. We welcomed him with flags and cheers. That’s my first memory of an American soldier. We were all so happy to welcome him,” said Choi. “I still remember that scene clearly. Looking back, I like to think he was a boy from the Midwest. ‘A boy from Iowa,’ as I call him in my mind.”

On September 15, 1950, General Douglas MacArthur led the successful amphibious landing at Incheon, known as Operation Chromite. The Incheon Landing was a turning point in the Korean War. It would eventually allow United Nations forces, led by the 1st Marine Division, to recapture Seoul and drive the North Korean army back beyond the 38th parallel.

“As we were trying to make sense of everything a few days after the battle, we were able to move around the area and see what had happened. Seoul had been mostly deserted, and the few North Korean soldiers left behind were injured. My father told us to treat them kindly if they asked for food or water, as they could become violent otherwise,” said Choi. “A few days after that, two Korean Marines, attached to the American Marines, came to our house. They weren’t interested in us, just trying to get information about our neighbors who had collaborated with the Communists. No American soldiers ever came to our house.”

Reversing the tide of the war, Chinese troops entered Korea by late October of 1950. Following the horrific Battle of Chosin Reservoir from November into December, North Korean forces had again reached Seoul by late December. They would recapture it for a second time in early January of 1951.

Choi’s entire family had fled the city just before Christmas. For a little boy, missing the holiday festivities was just one more joy that the war deprived him of. Choi remembered the mob scenes at train stations as crowds fought to escape.

“We were able to board an American military train that took us almost to Osan, a city near the air base. My mom’s village was about 15 miles north of it, so we got off the train there. South Korean soldiers were checking everyone, to root out infiltrators, and threatened to detain us,” said Choi. “Once again we experienced the kindness of American soldiers who gave us permission to continue on our way.”

Choi and his family had to walk the rest of the way to his mom’s village. As they reached the top of the mountain near her home, he could see the air base below with many American planes landing. The Osan Air Base had just recently opened, about 45 miles south of Seoul. It played a significant role in air operations during the war.

With few trains still running, the family was able to find space on one leaving for Daegu, often spelled “Taegu.” Choi and his uncle had to ride on top of the over-capacity railcar in the frigid winter temperatures.

Located in the southeastern part of the country, Daegu served as a critical defensive line for South Korean and United Nations forces. It was part of the “Pusan Perimeter,” from the early stages of the war, when North Korean troops had nearly overtaken the entire Korean Peninsula.

Because of his father’s connections in the city government, he had been able to arrange a temporary place of refuge. Choi had already experienced a lifetime of trauma in less than a year, at the age of 9. In just six months, the control of Seoul would change hands four times.

“The dropping of the nuclear bomb on Hiroshima forced the Japanese out of Korea. We owe America thanks for our liberation. And during the Korean War, American forces saved my life,” said Choi. “Many Koreans still appreciate what America did, though there are some who don’t see it that way. My role, as I see it, is to acknowledge our indebtedness to America and to find ways to give back.”

Choi said he had benefited greatly from the generosity of American society, particularly through his later education and training. Even before the Japanese occupation, which lasted 35 years, it was American doctors and missionaries who first established medical schools and universities in Korea.

“They educated Korean youth, including women, in the early 19th century. That was a monumental contribution. America played a significant role in helping to build the modern foundations of our nation,” said Choi.

Dr. Horace Newton Allen, an American Presbyterian missionary and physician, played a crucial role in establishing Korea’s first modern medical facility, Gwanghyewon, in 1885. The hospital later became part of what is now the Yonsei University’s College of Medicine, one of the most prestigious medical schools in South Korea. Choi graduated from the Yonsei University College of Medicine in 1965.

I moved to New York after I became a doctor. It was my first time in the United States. When I studied English in Korea, I remembered that the textbooks always said ‘Smith’ was a common last name in America. So I thought when I arrived I would get to meet many Smiths,” said Choi. “But the reality of Brooklyn in the 1960s was far different from what I had imagined. I never met a Mr. Smith.”

Choi was fortunate to have a successful career in both South Korea and the United States. After working as a professor at George Washington University, he was invited back to South Korea to chair a department at a new medical school in Suwon.

“It was near my mother’s village, where I had stayed during the war,” said Choi. “If I had stayed in Korea to practice medicine, I likely would never have achieved that high of a position. I wouldn’t have survived in that environment. So it felt like life had come full circle.”

Choi used his limited free time to revisit places from his childhood, and pay respects at his mother’s family graveyard. He also returned to Osan Air Base, where he had a chance encounter with the base commander.

“I told him the important role American forces played in my life, and I wanted to offer my help. At the time, I was the only American board-certified cardiologist on the peninsula,” said Choi. “The commander commissioned me as a lieutenant colonel on the spot. So, during the week I was a professor at the medical university. But on the weekend I wore a uniform and served in the U.S. military. It was very rewarding to care for the soldiers on the base.”

In 1993, at the age of 63, a former colleague from New York was working in Milwaukee. He offered Choi a position at the Medical College of Wisconsin, where he has remained for the past 20 years.

“The name of ‘Milwaukee,’ as you know, means ‘gathering place.’ It is a place where immigrants from all over the world have come together. Regardless of their country of origin, when they started new lives in Milwaukee, they became Americans,” said Choi. “For almost 250 years, America has conducted a great experiment. We are Americans, but America also stands for humanity, for the world.”

Choi believes that Milwaukee’s Korean American community, like the many immigrant communities that came before it, faced challenges in maintaining its cultural identity while integrating into American society.

“I see younger generations struggling to connect with their roots, while older generations hold too tightly to traditions. I believe it’s important to move beyond just clinging to our ethnic boundaries and instead focus on contributing to the broader human society,” Choi added. “My mother’s lessons have stayed with me throughout my life. I’ve been guided by a simple philosophy: to be a better human being before striving to be anything else.”

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora