This article is the first in a series that connects Milwaukee’s current social conditions with efforts in Alabama cities to publicly recognize their racial histories, to document the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement, and to extend and expand the Movement’s goals towards peace and reconciliation.

View the companion Photo Essay for this series.

A short but long anticipated trip to see the play “To Kill a Mockingbird” in rural Alabama, serendipitously expanded to become a trek along the state’s Civil Rights “trail.”

Eventually, the visit planned for a few days transformed itself into an itinerary of lessons in peace and reconciliation. And ultimately the entire experience brought me back to Milwaukee with new understandings and insights, and renewed commitments to equal justice and civil rights education in my own racially-stressed city.

HISTORY OF THE BIRMINGHAM BOMBING

Fifty-five years ago this week the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church by unknown Ku Klux Klan members, jolted the nation. This iconic event of violent intolerance catalyzed civil rights legislation that already was lurching forward via the strategic, non-violent demonstrations.

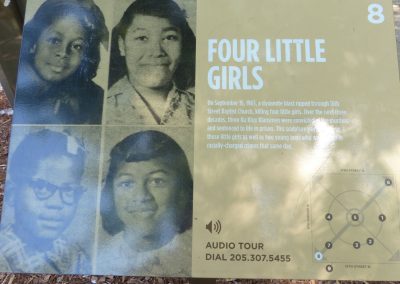

Four little girls, in the church’s “ladies lounge” preparing for Sunday services on a hot and cloudy morning, were killed in the explosion; twenty-two other congregants were injured, including the severely injured sister of one of the deceased girls. While dozens of other children- surrounded by brick rubble, glass shards, uncertainty and fear – escaped without injury, 14-year-olds, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins, and 11-year-old Denise McNair did not.

Riots in Birmingham’s streets erupted, literally, before the dust settled; within hours two boys were killed—also just as randomly as the girls. Governor George Wallace, an infamous segregationist, called in dozens of state troopers to assist local police in quelling the spontaneous, atypical violent protests, and in protecting white protesters who contended that they were the “real victims” of riot violence. Birmingham’s religious leadership called on President Kennedy to send regular Army troops into the strife-filled city. A previously scheduled anti-desegregation rally was cancelled but not before President Kennedy was hung in effigy. The U.S. Attorney General immediately sent twenty-five FBI investigators to the scene however it would be eleven days before any suspects were called in for questioning. With lurking allegations that J. Edgar Hoover among others suppressed inculpatory evidence, no prosecutions would be undertaken for a decade.

THE THREAT OF CIVIL RIGHTS IN BIRMINGHAM

White, segregationist Birminghamians, including those in governmental and law enforcement, were threatened by the emerging momentum of the long-stagnated Civil Rights Movement in Alabama. National media coverage of power abuses during the May 1963 Children’s March woke the country to the brutalities ordered, and the terror tactics enforced, against blacks.

Exposed, Birmingham stood down.

By July, the resultant desegregation of businesses, water fountains and lunch counters; the restructuring of the city’s government model; and President Kennedy’s televised address admonishing the city and introducing the Civil Rights Act of 1963, directly threatened and even endangered the segregationist culture and structures of Birmingham.

In just the month before the bombing, white Birminghamians saw the triumphal March on Washington—with Martin Luther King Jr.’s rousing speech echoing over The Washington Mall and down all the way to King’s pastorage in Alabama. In just the weeks before the bombing all Alabama students enrolled in schools that for the first time were required to be desegregated. The Federal government was raining down court orders and executive orders to protect the black students and to keep the schools open altogether, in contradiction to the Governor’s state orders to close all schools rather than permit desegregation.

The national press corps, in Birmingham to report the state’s resistance to school desegregation, immediately was on site to report the bombing, and did so in a manner that further exposed nationally the city’s tolerance of racially motivated violence – and the protection of its perpetrators.

BIRMINGHAM’S REACTION TO THE CIVIL RIGHTS “THREAT”

Racially motivated bombings were not unfamiliar to the city. The 16th Street Baptist Church routinely received bomb threats from KKK members, intending to disrupt civil rights meetings and services at the church. Targeting the church sent a not so surprising warning to its leadership. After all, the church hosted many of the movement’s organizing events and its non-violence protest education programs. Additionally, located kitty-corner from the city’s Kelly Ingram Park, the church along with the park served as staging areas for protests and rallies.

Since 1957 (the year the U.S. Supreme Court delivered its school desegregation decision) to September 1963, twenty bombs were planted at churches, black leaders’ homes and even the hotel where a visiting Martin Luther King, Jr. often stayed. The city had earned its nickname “Bombingham.” The bombings created injury and intimidation but no homicides.

However, this twenty-first bomb collapsed the church on innocents, and thereby quaked the conscience of the nation. Birmingham’s religious leaders called on President Kennedy to send regular Army troops into the strife-filled city. During the next days, angry but peaceful protests and counter rallies were held in several major U.S. cities. During the next week a joint funeral of three bomb victims was held, with Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering the eulogy to 8,000 attendees.

President Kennedy’s September 16th address to the nation propounded that

“If these cruel and tragic events can only awaken that city and state – if they can only awaken this entire nation – to a realization of the folly of racial injustice and hatred and violence, then it is not too late for all concerned to unite in steps toward peaceful progress before more lives are lost.”

In two months he would be lost to assassination; within the year, the initial “steps toward peaceful progress” were taken when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and again when he subsequently signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

No one heard the 16th Street Baptist Church’s sermon scheduled for September 15, 1963. It centered on the instruction in the Gospel of Matthew: to love one’s enemies. The sermon was entitled: “The Love That Forgives.”

THE PLACE OF REVOLUTION AND RECONCILIATION IN BIRMINGHAM

Despite continued racial strife, race-based violence and discrimination, Birmingham has realized civil rights advances. The first black mayor first was elected in 1979 and served for twenty years, leading civil rights initiatives not only to create a new image and spirit of shared power and biracial cooperation but also to commemorate the city’s history and struggles.

When the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute opened in 1992, the city coincidentally rededicated Kelly Ingram Park as “A Place of Revolution and Reconciliation.” The Institute bisects the intersection of 16th street and 6th Avenue – sited across the street both from the 16th Street Baptist Church and from Kelly Ingram Park.

The Institute’s labyrinth of exhibits chronologically explains Birmingham race relations and the Civil Rights Movement. The galleries eventually wind to a second-floor, bare corner with two windows that overlook the historic intersection. Outside the window to a visitor’s left is the 16th Street Baptist Church, long since restored and peacefully present behind a full-leafed tree catching a soft breeze. In the elevated space the view of the building is not obstructed; the busy intersection and changing traffic lights below do not distract. Outside the window to the right of the corner is sited the Four Spirits, a memorial sculpture of the bombing.

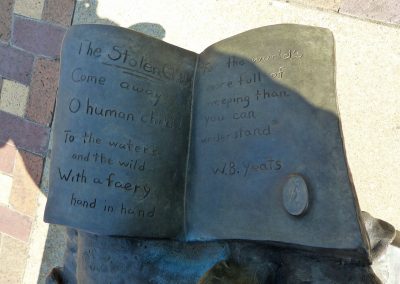

Dedicated five years ago, the metal sculpture serves as a memorial to the four girls killed in the church’s rubble. The sculpture depicts the four girls preparing for church services – moments before the explosion. One girl is releasing six doves into the air as she stands tiptoed upon a bench as another girl kneels upon the bench, adjusting the dress sash of the first girl. The sweet but mundane act of tying a bow is the last pose in the lounge recalled by Addie Mae Collins’ surviving sister. Another of the sculpture’s girls is standing and smiling as her hand directs the other three girls to attend the church service. The fourth girl sits on the bench with a book on her lap—etched with a partial quote from W. B. Yeats’ poem “The Stolen Child.” The sculpture’s base is inscribed with the name of the September 15, 1963 sermon—”A Love that Forgives.” The base also displays oval photographs and brief biographies of the four girls, the most seriously injured survivor, and the two teenage boys killed later that day.

While some artifacts of the bombing are on display, these views from the windows are the Institute’s installation about the bombing itself – displayed in silence absent docent, audio, video or written commentary.

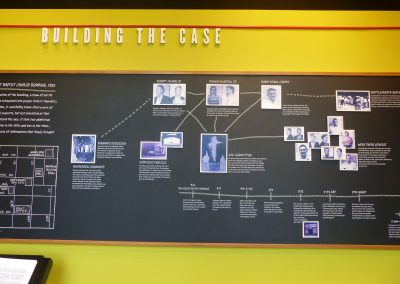

A slight turn farther to the left and the visitor sees a full wall displaying the timeline and legal strategy-maze of the ensuing prosecutions. While four local Ku Klux Klan members were named as suspects in the bombing in 1965, prosecutions would not occur and juries would not eventually convict three of the perpetrators until 1977, 2001 and 2002, respectively. The fourth complicit KKK member died years later never charged with any culpability for the bombing.

Near the timeline wall the Congressional Gold Medal is displayed, posthumously-awarded to the four girls in 2013, signed into law by President Barak Obama, and entrusted to the control and care of the Institute. Just beyond the medal is parked an original, armored police tank, used to patrol the streets and to intimidate protesters – and in September 1963 used to quell rioters.

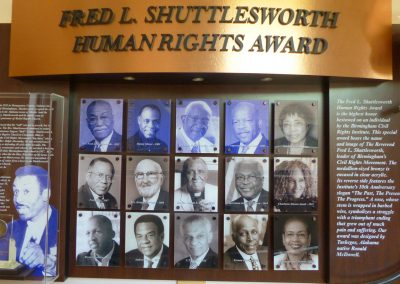

Turning one more time to leave the exhibits, a visitor passes a display of portraits: the fifteen recipients of the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award. Posted as the 2008 and sixth award recipient is current Milwaukee resident Rev. Joseph Ellwanger, the only white person to receive this prestigious award.

Before serving as pastor of Cross Lutheran Church on 16th street in Milwaukee, Joe Ellwanger served as pastor of St. Paul Lutheran, an African-American church in Birmingham. During his St. Paul ministry (1958-1967), Pastor Ellwanger became colleagues with Martin Luther King, Jr.; he joined with black religious leaders in strategy sessions, and he involved his congregation in mass meetings and in the Civil Rights Movement activities. He assumed a leadership role in community organizing—including the Birmingham demonstrations and the Selma, Alabama marches supporting voting rights.

Pastor Ellwanger became the only white minister in Birmingham who took such a prominent active role in supporting civil rights for blacks. However, at the time of the bombings, his race was not the only concern affecting his potential pastoral participation in the girls’ funerals. As he recounts in his book, Strength for the Struggle, one of the girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a congregant at St. Paul’s. When three of the families decided to have a joint funeral service, Pastor Joe’s grieving congregants wanted him to be included as a presider.

However, denominational differences between Baptist and Lutheran practices threatened accusations of “unionism” should the Lutheran participate in the Baptist service, and presented potential religious-based obstacles to presiding ecumenically. Ultimately, Pastor Joe read the Scripture lesson at the funeral, so he served as a participating minister. However the potential charge of “unionism” rather than cooperation presented yet another challenge in advancing the Civil Rights Movement. Present-day principles of ecumenism were in a nascent state in 1960’s America; their parallel development however for revolution and reconciliation emerged as an asset in both the civil rights and social justice movements. Milwaukee would benefit profoundly from Pastor Ellwanger’s embrace and exercise of ecumenism in his Cream City ministry and community organizing.

Pastor Ellwanger brought well-honed civil rights organizing to Milwaukee, founding and/or leading controversial refugee programs; youth-oriented ministry programs; and ecumenical justice programs including a long standing prison re-entry ministry (Project Return-1970), the Milwaukee congregation-based social justice organization Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied in Hope (MICAH–1988) and the grassroots, statewide social justice coalition of ecumenical religious congregations (WISDOM). In recent decades, Joe Ellwanger founded WISDOM’s statewide Reform Our Communities (ROC) Campaign to reform Wisconsin’s criminal justice system. He thereby links the 20th century’s Civil Rights Movement to the 21st century’s major civil rights issue, mass incarceration.

LESSONS LEARNED IN BIRMINGHAM

Despite the tragedies and triumphs of the historic Civil Rights Movement, the civil rights struggle continues in the present. Forty-nine years after the violent, race-based homicides in a Birmingham Church, Milwaukee awoke on a Sunday morning to violent race- and religious-based homicides in a local Sikh temple. Fifty-five years after the civil rights protests and rallies in Birmingham, Joe and Joyce Ellwanger still are marching and organizing and advocating for voting rights in Milwaukee, and for justice and freedoms of Milwaukeeans facing racially-disproportionate mass incarceration.

As in Milwaukee, Birmingham race relations have improved but civil rights discrepancies and disparities continue to exist and persist. Birmingham, however, has begun to acknowledge its history via public civil rights memorials – educating the living not only about its history but also acknowledging the past’s relevance to the present. This deliberate, conscious self-exposure informs and drives Birmingham towards its explicit aspirations of peace and reconciliation.