The Library of Congress has acquired and made available online the Omar Ibn Said Collection, which includes the only known surviving slave narrative written in Arabic in the United States.

Omar Ibn Said was leading a prosperous life in West Africa at the turn of the 19th century, devoting himself to scholarly pursuits and the study of Islam, when he was captured, carted across the globe, and sold as a slave in Charleston, South Carolina. An autobiography that Said penned during his time in America is the only Arabic slave narrative written in the United States known to exist today. And this precious manuscript was recently acquired and digitized by the The Library of Congress (LOC).

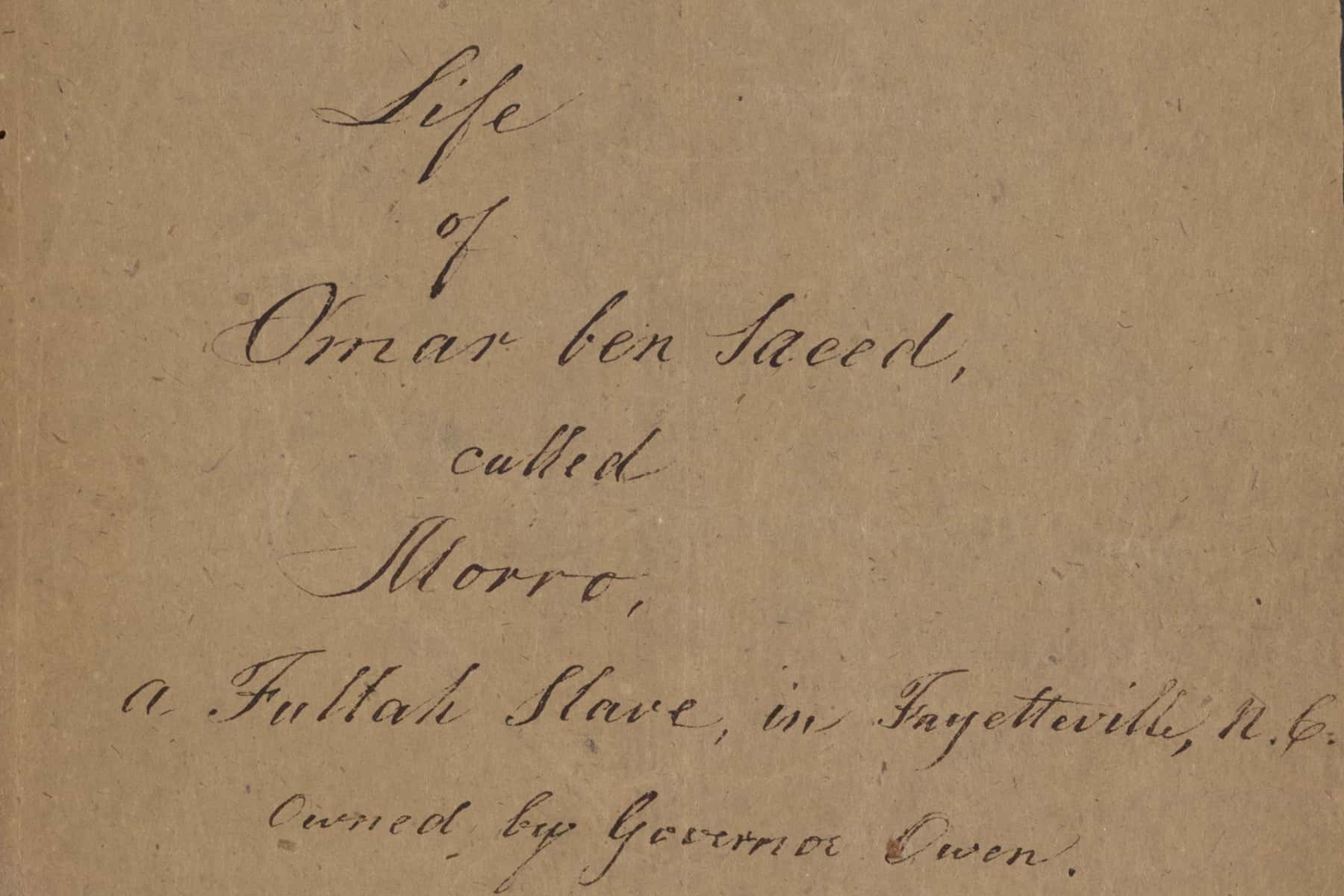

This manuscript is important not only because it tells the personal story of a slave written by himself, but also because it documents an aspect of the early history of Islam and Muslims in the United States. The Omar Ibn Said Collection consists of 42 original documents in both English and Arabic, including the manuscript in Arabic of “The Life of Omar Ibn Said” – the centerpiece of this unique collection of texts.

“Paper and ink are resilient and long-lasting, though they can be battered and damaged. Our aim was to strengthen and preserve the manuscript, while still allowing its previous history and life to remain evident,” said Shelly Smith, head of the LOC’s Book Conservation Section.

Other manuscripts include texts in Arabic by another West African slave in Panama and from individuals located in West Africa. The collection was digitally preserved and made available online for the first time by the Library of Congress.

“Although the Omar Ibn Said Collection is recognizable, it has been moved between different private owners and even disappeared for almost half a century,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “To have it preserved at the Library of Congress and made available to everyday people and researchers across the world will make this collection an irreplaceable tool for research on Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries and will shed light on the history of American slavery.”

The collection was assembled in the 1860s by Theodore Dwight, an abolitionist and one of the founders of the American Ethnological Society. It was passed from owner to owner over the centuries, at one point disappearing for nearly 50 years, before The Life of Omar Ibn Said reached the Library of Congress. By then, it was in a fragile state, and conservationists quickly got to work preserving it.

Though it is only 15 pages long, Said’s manuscript tells the fascinating and tragic story of his enslavement. In Charleston, Said was sold to a slave owner who treated him cruelly. He ran away, only to be re-captured and jailed in Fayetteville, North Carolina. There, he scrawled in Arabic on the walls of his cell, subverting the notion that slaves were illiterate.

“This rare collection is extremely important because Omar Ibn Said’s autobiography is the only known existent autobiography of a slave written in Arabic in America,” said Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress. “The significance of this lies in the fact that such a biography was not edited by Said’s owner, as those of other slaves written in English were, and is therefore more candid and more authentic.”

Said soon was purchased by James Owen, a statesman and brother of North Carolina Governor John Owen. The brothers took an interest in Omar, even providing him with an English Qu’ran in the hope that he might pick up the language. But they were also keen to see him convert to Christianity, and even scouted out an Arabic Bible for him. In 1821, Said was baptized.

As an erudite Muslim who appeared to have taken up the Christian faith, Said was an object of fascination to white Americans. But he does not appear to have forsaken his Muslim religion. According to the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, Said inscribed the inside of his Bible with the phrases “Praise be to Allah, or God” and “All good is from Allah,” in Arabic.

“Because people were so fascinated with Umar and his Arabic script, he often was asked to translate something such as the Lord’s Prayer or the Twenty-third Psalm,” the North Carolina Department of Cultural History notes. “Fourteen Arabic manuscripts in Umar’s hand are extant. Many of them include excerpts from the Qu’ran and references to Allah.”

Writing in a language that none of his contemporaries could understand had other advantages, too. Unlike many other slave narratives, Said’s autobiography was not edited by his owner, making it “more candid and more authentic,” says Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the LOC’s African and Middle Eastern Division.

“It is an important documentation that attests to the high level of education and the long tradition of a written culture that existed in Africa at the time,” added Deeb. “It also reveals that many Africans who were brought to the United States as slaves were followers of Islam, an Abrahamic and monotheistic faith. Such documentation counteracts prior assumptions of African life and culture.”

Said died in 1864, one year before the United States legally abolished slavery. He had been in America for more than 50 years. Said was reportedly treated relatively well in the Owen household, but he still died a slave.

“To have the manuscript preserved at the Library of Congress and made available to everyday people and researchers across the world will make this collection an irreplaceable tool for research on Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries,” says Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, one that she predicts will further “shed light on the history of American slavery.”