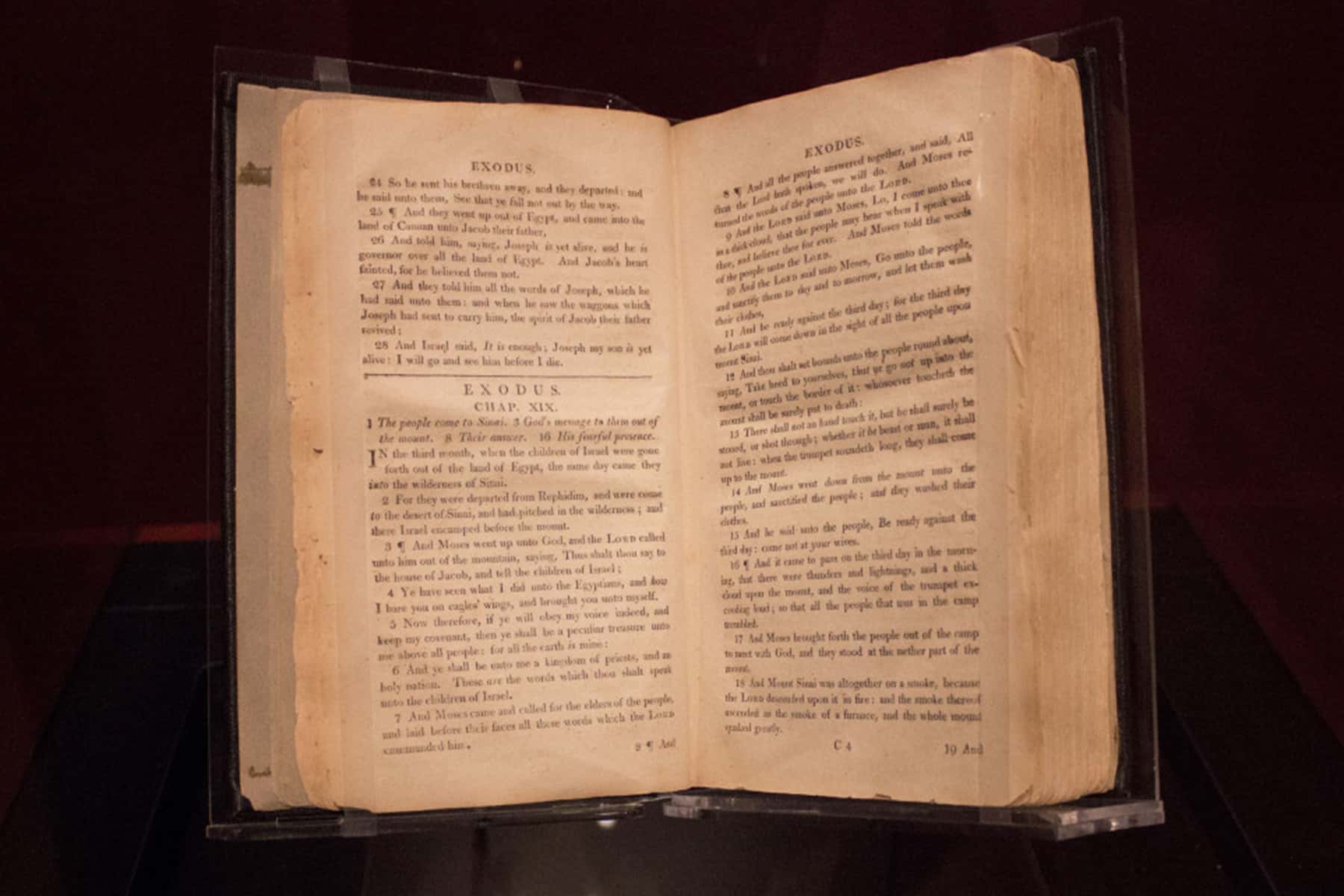

When 19th-century British missionaries arrived in the Caribbean to convert enslaved Africans, they came armed with a heavily edited version of the Bible. Any passage that might incite rebellion was removed. Gone, for instance, were references to the exodus of enslaved Israelites from Egypt.

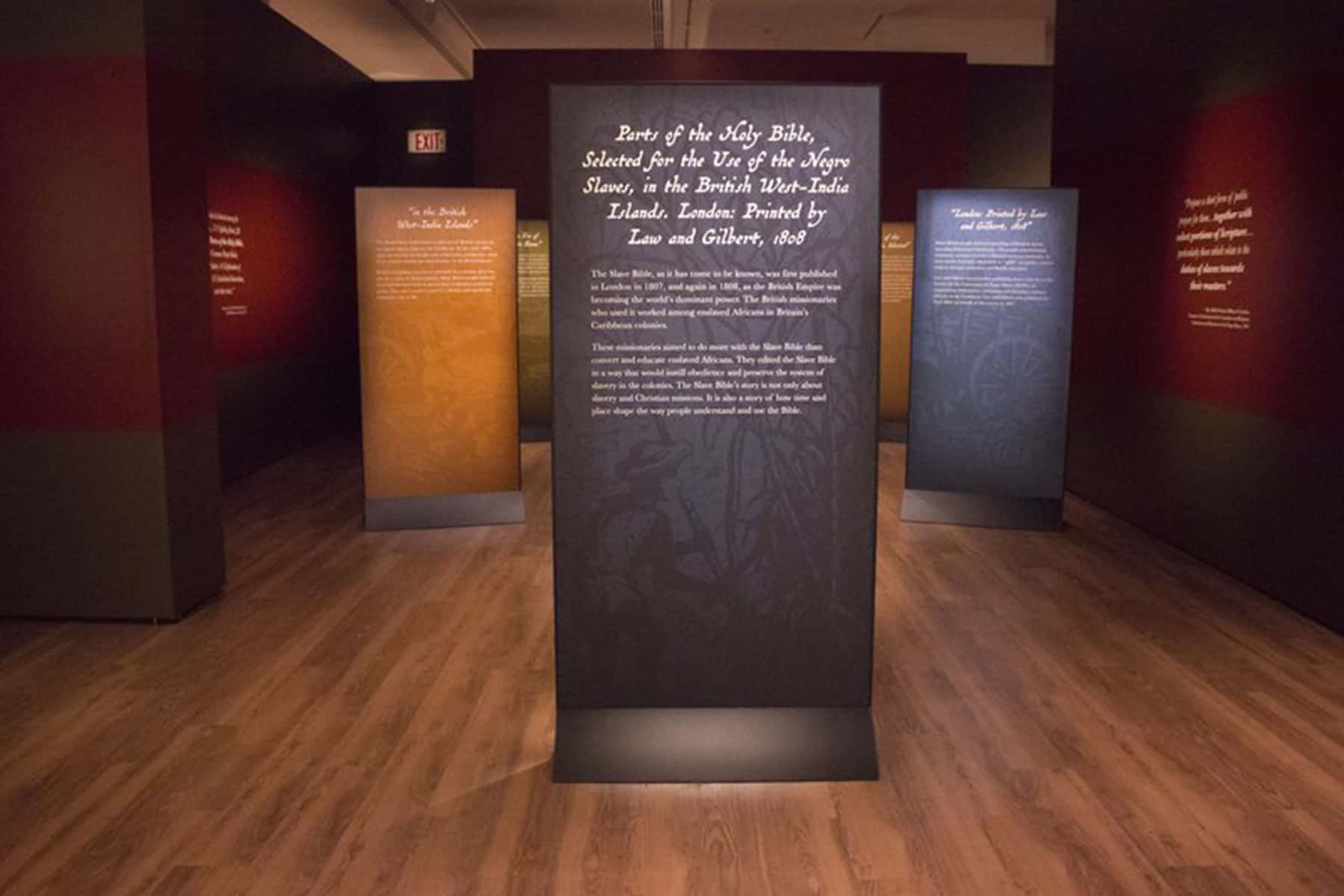

Today, just three copies of the so-called “Slave Bible” are known to exist. Two are held in the United Kingdom, and one is currently on view at the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC. The bible is the centerpiece of an exhibition titled Parts of the Holy Bible, selected for the use of the Negro Slaves, in the British West-India Islands, which explores how religion was used to bolster the economic interests of the British Empire.

The abridged work was first printed in London in 1807, on behalf of the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves. The missionaries associated with this movement sought to teach enslaved Africans to read, with the ultimate goal of introducing them to Christianity. But they had to be careful not to run afoul of farmers who were wary about the revolutionary implications of educating their enslaved workforce. The British West-India Islands (modern-day Jamaica, Barbados and Antigua) “formed the heart” of England’s overseas empire, after all, and it was powered by millions of enslaved Africans forced to work on sugar plantations.

“This can be seen as an attempt to appease the planter class saying, ‘Look, we’re coming here. We want to help uplift materially these Africans here but we’re not going to be teaching them anything that could incite rebellion,’” Anthony Schmidt, the Museum of the Bible’s associate curator of Bible and Religion, said Martin.

That meant the missionaries needed a radically pared down version of the Bible. “A typical Protestant edition of the Bible contains 66 books, a Roman Catholic version has 73 books and an Eastern Orthodox translation contains 78 books,” the museum says in a statement. “By comparison, the astoundingly reduced Slave Bible contains only parts of 14 books.”

Gone was Jeremiah 22:13: “Woe unto him that buildeth his house by unrighteousness, and his chambers by wrong; that useth his neighbour’s service without wages and giveth him not for his work.” Exodus 21:16—“And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death”—was also excised. In their place, the missionaries emphasized passages that encouraged subservience, like Ephesians 6:5: “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.”

The museum’s Slave Bible is on loan from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, which collaborated on the exhibition, as did the Center for the Study of African American Religious Life at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The text has been on display at the Museum of the Bible since last year, but visitors were so shocked and fascinated by the book that the museum decided to center an exhibition around it. A series of events and talks focused on the Slave Bible are planned around the show, which closes in April.

Though tools like the Slave Bible may have been used to repress rebellion, it did not stop enslaved people in the Caribbean from fighting for their freedom. “Enslaved people constantly rebelled against slavery,” according to the U.K. National Archives, “right up until emancipation in 1834.”

Michel Martin and Smithsonian Staff

Museum of the Bible

Originally published as Heavily Abridged ‘Slave Bible’ Removed Passages That Might Encourage Uprisings