One advocate calls Wisconsin the ‘darkest of dark money states’ as millions in secret spending flows into races for governor, Legislature, and State Supreme Court.

At age 2, Yasmine Clark was lead-poisoned so severely that she had to be hospitalized for emergency chelation treatment to cleanse her blood of life-threatening levels of the heavy metal.

At age 5, Yasmine was again diagnosed with lead poisoning. She suffered significant brain damage. Her IQ declined. She developed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

So, in 2006, at age 5, Yasmine became a plaintiff in a Milwaukee County lawsuit filed against multiple paint companies, including National Lead, now called NL Industries, which had made lead paint like that found in the rental homes where she was raised in Milwaukee.

She was among about 170 Wisconsin children named as plaintiffs in lawsuits against the paint companies. The suits sought compensation for medical expenses and other damages for what their attorneys said were severe and permanent injuries from ingesting lead-tainted paint chips.

While these children had compelling personal stories, NL Industries had something even more powerful on its side: Republican politicians facing recall elections in 2011 and 2012 who secretly benefitted from $750,000 contributed by NL’s owner, Harold Simmons, to an “independent” political group.

At the request of NL’s lobbyist, Republicans inserted a handful of words into the 2013-15 state budget that sought to halt such lead-paint lawsuits, including the one filed by Yasmine, according to a memo obtained by the Center for Media and Democracy, a left-leaning watchdog organization that exposes corruption in government.

The politicians’ effort — ultimately blocked by judges — demonstrates the power of secret contributions to reshape state law while the public is kept in the dark.

Contributions up, citizens alarmed

The flow of cash to outside groups seeking to influence Wisconsin elections has widened since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision held that corporations could not be barred from making so-called independent expenditures. The court declared that corporations have the same First Amendment free speech rights as do people.

In 2015, the Wisconsin Supreme Court threw out a state-led John Doe investigation into coordination between Gov. Scott Walker’s campaign, Club for Growth and other “issue ad” groups by overturning a state law that prohibited such coordination. The four conservative members of the court who ordered an end to the investigation had themselves been beneficiaries of an estimated $8 million in outside spending by the same political groups under scrutiny in the Walker investigation.

Later that year, the Wisconsin Legislature passed a law that allows corporations to donate to political parties and legislative campaign committees. The law overturned a corporate contribution ban that had been in place since 1905. Republicans said the change gave corporations parity with labor unions, which could contribute to political parties and which traditionally supported Democrats.

The loosening of Wisconsin’s rules comes as a large majority of the American public is concerned about the influence of money in politics. A nationwide poll released in June found that 80 percent of respondents believe the “influence of money in politics” is getting worse rather than better. The poll commissioned by the bipartisan Democracy Project found that 77 percent of respondents agreed that “the laws enacted by our national government these days mostly reflect what powerful special interests and their lobbyists want.”

Activists, alarmed by the rise of corporate influence on politicians and the electoral process, are fighting back.

United to Amend, a nonpartisan national campaign active in Wisconsin, aims to get local and state governments to endorse changing the U.S. Constitution to counteract the effects of Citizens United. And several states, including Arizona, Colorado, Massachusetts, Missouri, North Dakota and South Dakota, have or are working toward measures on the November ballot that seek to further regulate campaign spending. Activists in two more states — Oregon and Wyoming — are pushing ballot measures for 2020.

Four powerful words

The Guardian news organization, citing leaked documents from the Wisconsin John Doe investigation, found that lead executive Simmons had made donations totalling $750,000 to Wisconsin Club for Growth between April 2011 and January 2012. The spending was used to beat back recall elections against Walker and Republican senators sparked by passage of the controversial Act 10 collective bargaining law.

The donations came both before and after Republicans who control the Legislature approved two law changes in 2011 and 2013 that were beneficial to NL Industries. The change in 2013 involved four words inserted into an omnibus budget motion passed in the early morning hours by the Joint Finance Committee.

Those words, “whenever filed or accused,” effectively halted the claims of Yasmine and the other 170 or so lead-poisoned children by retroactively exempting NL Industries and the other lead-paint manufacturers from liability.

NL, along with Sherwin-Williams and Atlantic Richfield Co., spent $367,500 on a total of 710 hours of lobbying in an effort to change the law to dismiss the cases against the companies, according to the Wisconsin Ethics Commission lobbying records cited in the Yasmine lawsuit.

In the memo obtained by the Center for Media and Democracy, Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, R-Juneau, documented the request by NL lobbyist Eric Petersen to insert the language into the budget.

Attorney Peter Earle, who represented Yasmine in the lead-paint case, said the change seeking to halt the lawsuits was made possible by such secret contributions. He said the language inserted into the 2013-15 budget was “obscure and last-minute” and noted that it had been added “without notice, sponsors or a public hearing.”

“These children were first stripped of their God-given right of cognition, executive function and impulse control by the knowing misconduct of the lead paint companies, and then they were stripped of their right to their day in court because of this corrupt coordination,” the Milwaukee attorney said. “It was done because of greed. Politicians chose the interests of their donors and corporate special interest groups over the rights of innocent children.”

The secretive budget move was short-lived, however. Milwaukee County Circuit Judge David Hansher found that Yasmine had the right to bring her lawsuit, and in the process nullified the 2013 law change designed to benefit lead-paint manufacturers, a decision that was upheld on appeal.

“The sole inquiry before the Court is whether it is constitutional for the Legislature to deprive innocent and injured plaintiffs of their vested right to pursue claims against manufacturers and sellers of white lead carbonate,” Hansher wrote. “In this Court’s view, it is not.”

In 2017, Hansher granted a motion filed by Earle to dismiss the case with the option of re-filing it at a later time. Earle said he cannot discuss the reasons for the dismissal.

‘Darkest of dark money states’

Wisconsin and Florida are the only two states in the nation that have legalized coordination between candidates and outside special interest groups that engage in “issue advocacy,” according to Daniel Weiner, senior counsel at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, which aims to reform, revitalize and defend democracy and justice.

Contributions to “issue ads,” which often support or oppose candidates without using words including “vote for” or “vote against,” are not required to be reported to the Wisconsin Ethics Commission.

David Buerger, staff counsel at the ethics commission, said the state now bans coordination only involving “express advocacy” — communication that specifically calls for the election or defeat of a candidate.

In a 2015 move that further obscures the influence of money on politics, Wisconsin’s Legislature on a party-line vote eliminated the requirement that candidates list the employers of their donors, removing a key detail behind publicly reported campaign contributions.

In the same bill, lawmakers legalized unlimited contributions to political parties and legislative campaign committees, except for corporations and groups such as labor unions, which can contribute up to $12,000 a year.

A Marquette Law School poll found that most citizens of Wisconsin disagreed with the Legislature’s 2015 decision to remove contribution limits on state political parties. In a poll, 61 percent of respondents said they opposed unlimited contributions, while 13 percent supported them. Another 25 percent said they had not heard enough on the issue.

Taken together, these changes have made Wisconsin the “darkest of dark money states,” said Jay Heck, executive director of the Common Cause in Wisconsin, which promotes clean, open and responsive state government.

Matt Rothschild, executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, offers a similar assessment.

“In my opinion, legalized bribery is rampant these days because of the change in the campaign finance law in 2015 and because of the Wisconsin Supreme Court decision (legalizing coordination),” said Rothschild, whose group also works for clean government. “So we live in a state where Wisconsin is open for bribery.”

Campaign law changes controversial

Mike Wittenwyler, a Madison attorney who specializes in campaign finance issues and who has represented outside political groups, disagrees, saying it had been more than 40 years since Wisconsin updated its campaign finance laws.

The last major rewrite was in the 1970s, he said, prior to several key court decisions that clarified the limits and rights of donors and candidates.

“What happened with Wisconsin’s campaign finance laws was long overdue,” Wittenwyler said. “We made great strides compared to where we were five years ago.”

Unlike some states, Wisconsin does have some limits on individual campaign contributions, including $20,000 for statewide offices including governor, attorney general and state Supreme Court justice.

Among the states that have limits, however, “Wisconsin is one of the worst, because the Wisconsin Supreme Court has made it so easy to circumvent them,” Weiner at the Brennan Center said.

He added that secret campaign contributions can come from interests on both the left and right, especially in state elections.

“On the state level, we see a lot more ‘Company X wants a mining concession,’ or something like that,” Weiner said. “And they put a lot of dark money in to basically influence legislative officials to get what they want.”

That is not just an idle example. Documents briefly unsealed during the John Doe investigation show that Gogebic Taconite secretly donated $700,000 to Wisconsin Club for Growth during the recalls in 2011 and 2012.

The company had plans for a massive open pit iron ore mine, but it demanded changes in mining laws. In 2013, Walker signed the bill loosening restrictions — a bill that Senate Majority Leader Fitzgerald acknowledged in a video was written by Gogebic Taconite. After several years, the company abandoned the project as not feasible.

Menard Inc. owner John Menard also has seen his company’s fortunes rise after secretly donating to Wisconsin Club for Growth. Yahoo News reported in 2015 that Menard wrote checks totalling $1.5 million to the group. After that, the company was awarded a $1.8 million dollar tax credit from Wisconsin Economic Development Corp.

Under previous governors, the company received citations for violating state environmental laws, including a $1.7 million fine levied against Menard personally and his company, for illegally dumping hazardous wastes.

People vs. Citizens United

Some advocates for stricter campaign finance laws feel that the only way to blunt such corporate influence over the political system is with a constitutional amendment to override the Citizens United decision.

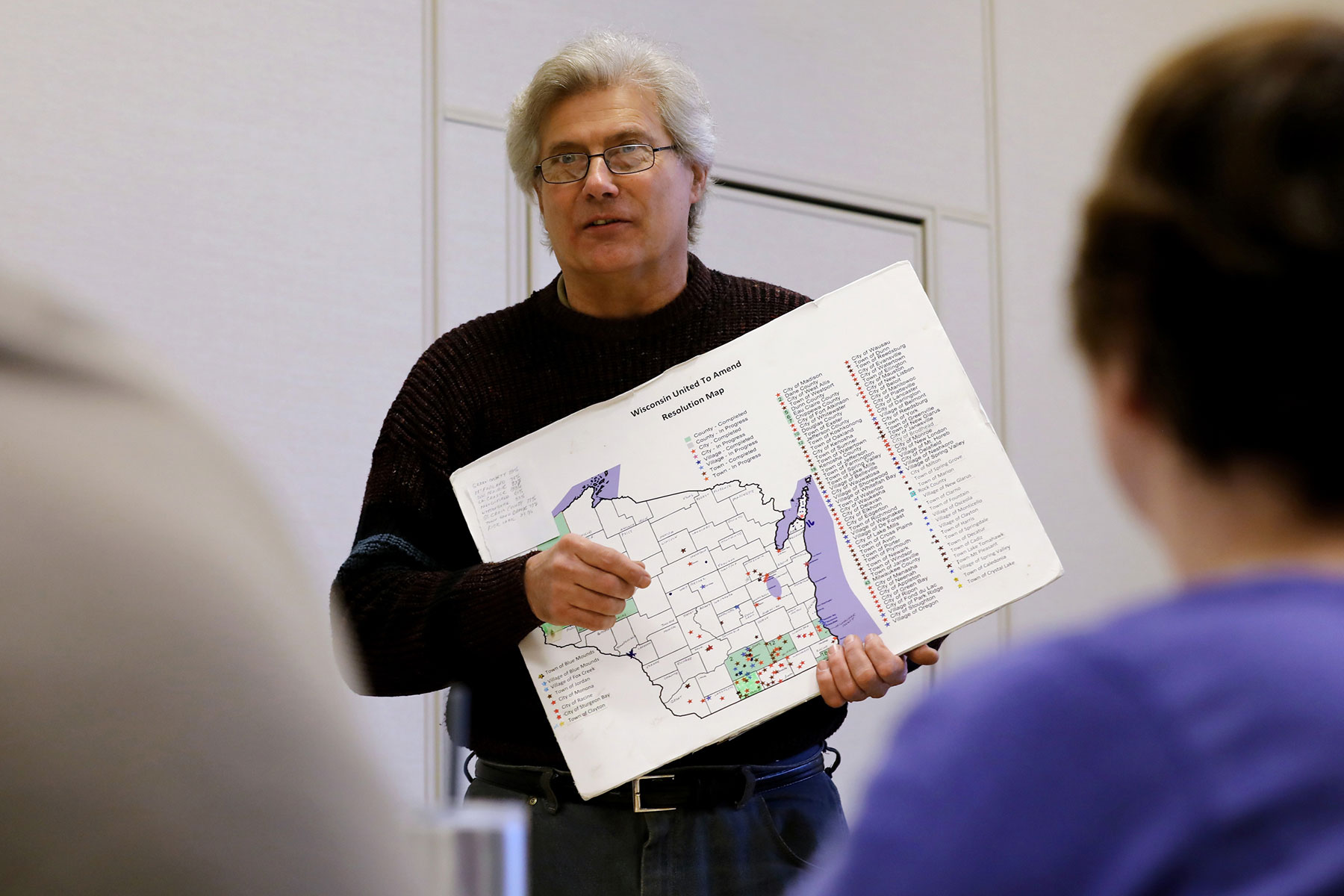

Wisconsin United to Amend is mobilizing people to sign a petition and to convince city councils and town and village boards to vote on resolutions calling for this constitutional amendment.

The campaign’s messages are: “Money is not speech” and “Corporations are not people.”

Currently, more than 130 local governments in Wisconsin and 19 state legislatures have passed the resolution.

“More and more people are understanding … these politicians cannot fix it, because they are bought by those who don’t want to fix it,” said George Penn, a representative from South Central Wisconsin United to Amend. “Whatever you care about, our politicians cannot solve it. Therefore it becomes a root cause to all our problems.”

Penn, who travels the state visiting town and village boards and city councils, is passionate about the issue. He wants future generations to experience the America where he grew up.

“To me, it is about the future of our children and grandchildren,” Penn said. “I believe I grew up in the best economy and the best democracy of mankind, and I believe we lost democracy.”

Many on the left see the Citizens United decision as a stab at the heart of democracy. Wittenwyler takes the opposite view. He believes the decision expands free speech rights.

“We need to have the broadest protection of freedom of speech. I don’t want a government agency telling me what media resources I can and cannot hear. Most media organizations are corporated, nonprofits are corporated. There are so many entities that are corporated,” Wittenwyler said.

“Everyone should be able to speak and you shouldn’t make arbitrary decisions based on how an entity may or may not be established,” he added. “I want to live in a society where everyone is allowed to speak without any government oppression of what you’re going to hear.”

Voter John Tyler, speaking outside his Lake Mills polling station during the Aug. 14 primary election, said corporations have too much influence in our democracy.

“It’s troubling to me that corporations are so-called ‘people’ and they can give millions of dollars, and a bunch of the money given is dark money, so we have no idea who’s trying to buy or influence our legislatures,” Tyler said. “And so how is the regular person supposed to stand up and be counted compared to corporations that give millions of dollars and influence policy and have the legislatures just do what they wanted?”

‘Your vote counts in Wisconsin’

Rothschild said he believes elections and governing are becoming a battle between wealthy special interests and donors, with regular people left out.

“A lot of elected officials and candidates don’t think they need to go to every town or every district anymore because they could just get huge amounts of money from this handful of wealthy individuals or corporate interests,” Rothschild said. “I’ve traveled around the state and people say ‘Our legislator never comes here.’ ”

Weiner said that Wisconsin officials’ loosening of campaign finance rules appears to run counter to what most citizens want these days.

“I think in some ways Wisconsin is going to increasingly find itself out of step with the national mood,” he said. “If anything, you’re seeing people wanting stronger (campaign finance) rules and stronger safeguards.”

Eric Blumreich, a Green Bay resident who participated in Wisconsin Public Radio’s Beyond the Ballot series, thinks money is corrupting Wisconsin’s political system.

“I feel that there are two major implications to the nature of politicians in our increasingly money-oriented campaigns,” Blumreich said. “The first is that a politician must appeal to those who hold the purse strings when they should be accountable to the individual constituents. The second is that they have to present themselves as ideologues and purists.”

But Blumreich believes citizens still have the power to create change in Wisconsin.

“The 2016 presidential election was decided by razor thin victories for (President) Trump in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania,” Blumreich said in an email. “In my opinion, this indicates that your vote counts in Wisconsin, and that vote is perhaps the best indicator of power when it comes to political power and having a voice.”

Pawan Naidu

Bergeron Media, Coburn Dukehart, and Cameron Smith

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.