Veteran journalist Kevin P. Keefe and Scott Lothes, president of the Center for Railroad Photography &a Arts, compiled a photo book chronicling the life and photography of Wallace W. Abbey.

The Milwaukee-based photographer and magazine editor captured this city’s bustling railroad scene at its peak before ultimately getting a job overseeing communications for the Milwaukee Road.

The book, Wallace W. Abbey: A Life in Railroad Photography (Railroads Past and Present), features more than 175 gorgeous photos from Abbey’s collection, as well as details about Abbey’s work ranging from his time at Trains magazine in Milwaukee to running public relations for the Milwaukee Road during the firm’s high-profile bankruptcy.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

Even if the Milwaukee Road was not Wally Abbey’s favorite railroad, you might have thought otherwise based on the body of work he created once he arrived at Trains magazine as an editor in 1950. From the magazine’s office on the north edge of downtown Milwaukee, Abbey ranged across a railroad empire that often dominated the city’s landscape.

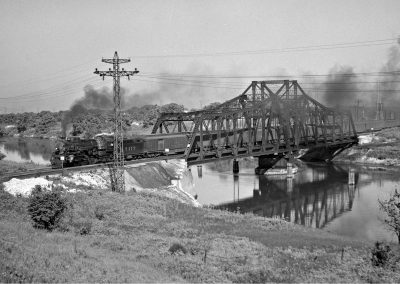

Abbey’s timing was perfect. The Milwaukee Road was flying high. It was the era of the Hiawathas, the railroad’s celebrated orange-and-maroon streamliners, new versions of which debuted in 1948. The Milwaukee was locked in a fierce battle with its key rivals for the Chicago-Twin Cities passenger trade, the North Western’s 400 streamliners and the Burlington’s Zephyr trains, and Abbey’s newly adopted city was in the middle of the action.

A favorite vantage point was the Everett Street passenger station, overlooking today’s Zeidler Park at 4th Street and Michigan, a brooding, gothic rock pile a few blocks south of the Trains office. Behind the building, a lofty train shed was accessible at each end by sweeping curves of track, hemmed in by surface streets on all sides. For the photographer, it was a vantage point loaded with potential, and Abbey made the most of it, contrasting the sleek, modern Hiawathas with a vintage cityscape looming beyond the platforms.

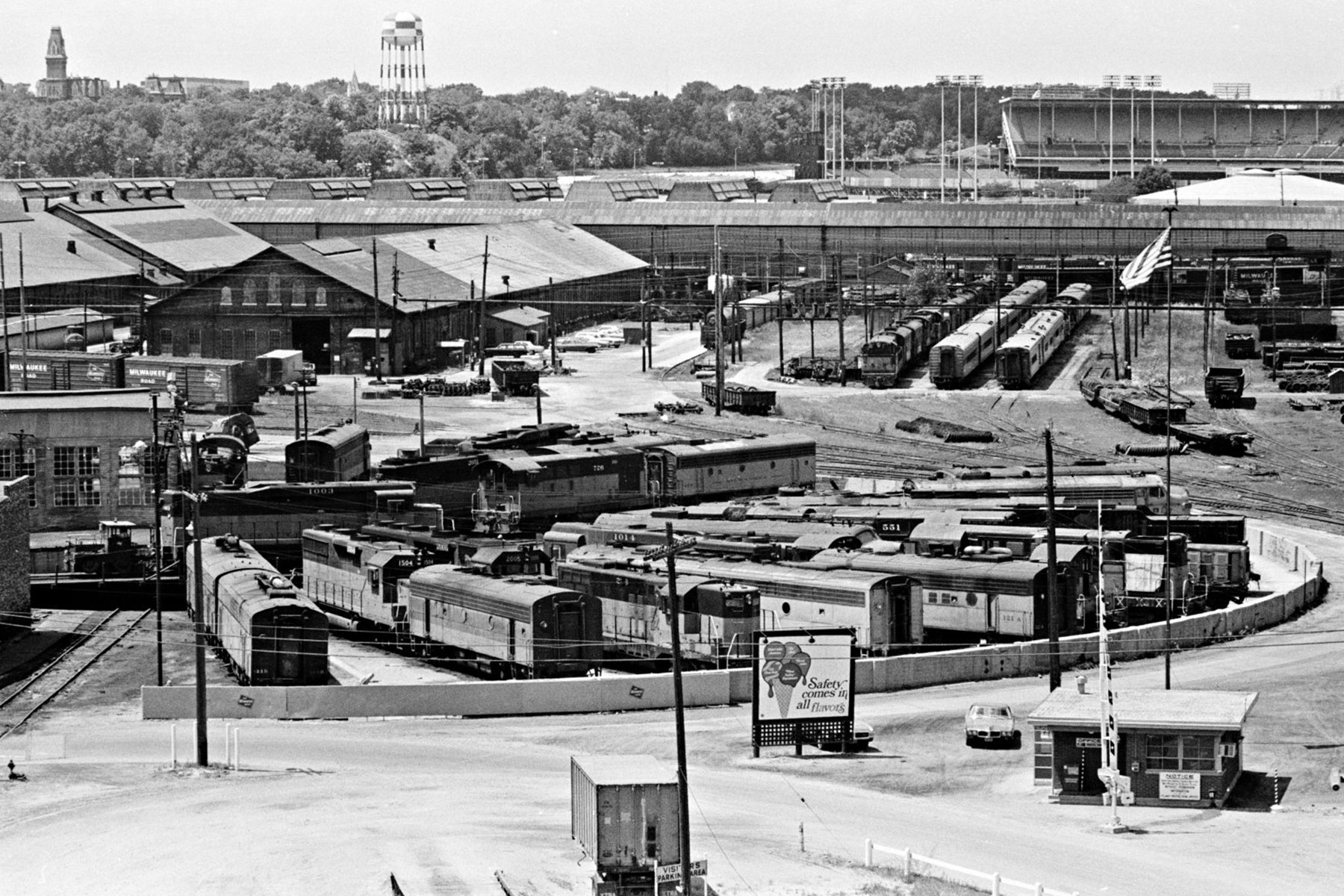

There was plenty more for Abbey to shoot. Just a mile or so west of the depot, the railroad’s West Milwaukee shops sprawled across the bottom of the Menomonee River Valley, a vast panorama of freight yards, locomotive and car repair shops, office buildings, and two roundhouses, all easily visible from the 35th Street viaduct. Over the years Abbey also ranged far from the railroad’s operating headquarters, photographing Milwaukee Road passenger and freight trains in the Chicago region and, later during his Soo Line years, in and around the Twin Cities.

Then there was the Beer Line, an Abbey favorite. This industrial branch reached down into Milwaukee from the north, hugging the west side of the Milwaukee River until it fanned out across a narrow corridor near downtown to serve the team tracks of the Schlitz, Pabst, and Blatz breweries, as well as several tanneries. The Beer Line was a singular stretch of railroad, emblematic of the city. An idiosyncratic fleet of exotic Alco and Fairbanks Morse diesel switchers tended its tangle of sidings, and the air smelled of malt and rendering. Abbey returned to photograph this quirky stretch of railroad again and again.

Abbey left Milwaukee in 1954 and moved back to Chicago for a job with the Association of Western Railways, but he sustained his ties to the Milwaukee Road, which was an association member. He got to know various company executives at countless meetings and conferences. Those contacts continued in his next job as a Midwest editor at Railway Age, and later in his public relations post at Soo Line in Minneapolis, which shared much of the Milwaukee Road’s territory.

Those contacts paid off in 1975. Abbey was a bit adrift, having difficulty drumming up new business for his Abbey Enterprises PR firm and, it seems, losing his passion for working for himself. He had closed an office he was renting and moved his work onto a desk in the basement at home. Then, he heard that the man handling Milwaukee Road’s advertising and public relations was leaving. He knew Worthington Smith, then president of the railroad, and inquired about the position.

“Worth’s reply to me was neither yes or no,” recalled Abbey, who welcomed a move to 516 West Jackson in Chicago. “It was more like, ‘When can you be here?’ And so I assumed the new position of director of corporate communications for the Milwaukee Road. It wasn’t evident, to me at least, but strenuous times were about to begin.”

The strain was already showing on the company. By the mid-1970s the Milwaukee Road was locked in an existential financial struggle as traffic declined and a host of historical bad decisions began catching up on management, notably the railroad’s money-losing Pacific Extension across Montana, Idaho, Washington, and into Seattle, opened in 1909. Deferred maintenance for track and locomotives had become obvious. The railroad’s huge shop complex in Milwaukee was beginning to look rundown.

Abbey stepped into a public-relations situation that was equally problematic. “I had the responsibility for what had once been a sizable advertising campaign. But I had no advertising budget. I had a staff that on paper contained thirteen job positions, three of which were unoccupied. The Milwaukee was something of a laughing-stock in the railroad public relations trade.” Still, he threw himself into the work, reporting directly to Smith and Chairman William J. Quinn.

Then came what Abbey called “the fateful, but not fatal, weekend,” December 19, 1977, when the Milwaukee Road filed for bankruptcy. Suddenly Abbey was not only dealing with the usual challenges of running a railroad’s corporate communications, but also explaining the railroad’s troubles to key constituencies, not least of which was the bankruptcy court. He became a constant companion of the trustee, first Stanley E. G. Hillman and later Richard B. Ogilvie, both of whom believed the railroad’s only salvation lay in abandoning the Pacific Extension and retrenching to a core Midwest system.

Abbey’s responsibilities were weighty, but he embraced them. “The bankruptcy of the Milwaukee Road prompted continuous and nearly always erroneous assumptions, rumor, and misconstructions of fact,” he later recalled. “To control the quality of the information output from his office, the Trustee appointed two official spokesmen: the president and me. The president was too busy at the time to be available very often. I thus became, in effect, the ‘voice’ of the reorganization process outside the courtroom.”

It was a tough position to be in, but Abbey got high marks for performance under fire. Joseph A. Swanson, a professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and a close observer of the Milwaukee debacle, admired his efforts. “Abbey was a guy who could put the best foot forward. The story was difficult to tell in a positive way, but that’s exactly what he did.”

Frustrating as the job likely became, Abbey still thought like a journalist. He knew he was uniquely qualified to document what was happening, especially with his camera. Thus did he make a number of heartbreaking photographs of the railroad during a multi-day inspection trip with the trustee, creating a sad record of worn-out diesels, deteriorating track, and the always lovely scenery along the doomed Pacific Extension.

Years later, Abbey planned but never finished a book about the Milwaukee Road. Rarely the sentimentalist, he gave it the working title “Leaky Boat.”

The Milwaukee School of Engineering‘s Grohmann Museum is host to an exhibition of 40 photos that runs through August 19. An exhibit on the Beer Line, one of Abbey’s favorite subjects to shoot, is also making the rounds through Wisconsin breweries.

Kevin P. Keefe and Scott Lothes

Wallace W. Abbey Collection and Center for Railroad Photography & Art