Once the fabric of Milwaukee for six decades, and all but forgotten now, manufacturing sites in the city produced military armament used around the world and helped mankind leave the gravity of Earth.

Established in 1948 in a six-story plant on the northeast side, the Milwaukee operations of Delco Electronics – known as Delphi Electronics & Safety at its closing in 2008 – had a leading role in the field of precision guidance systems and automotive components.

The company played a key role for years in research, development, and production of electro-mechanical devices for military use and space exploration. It began with 25 people manufacturing bomb sights for the U.S. Air Force, and by 1957 the company was producing the guidance system for the Thor missile – the first ballistic missile in the United States.

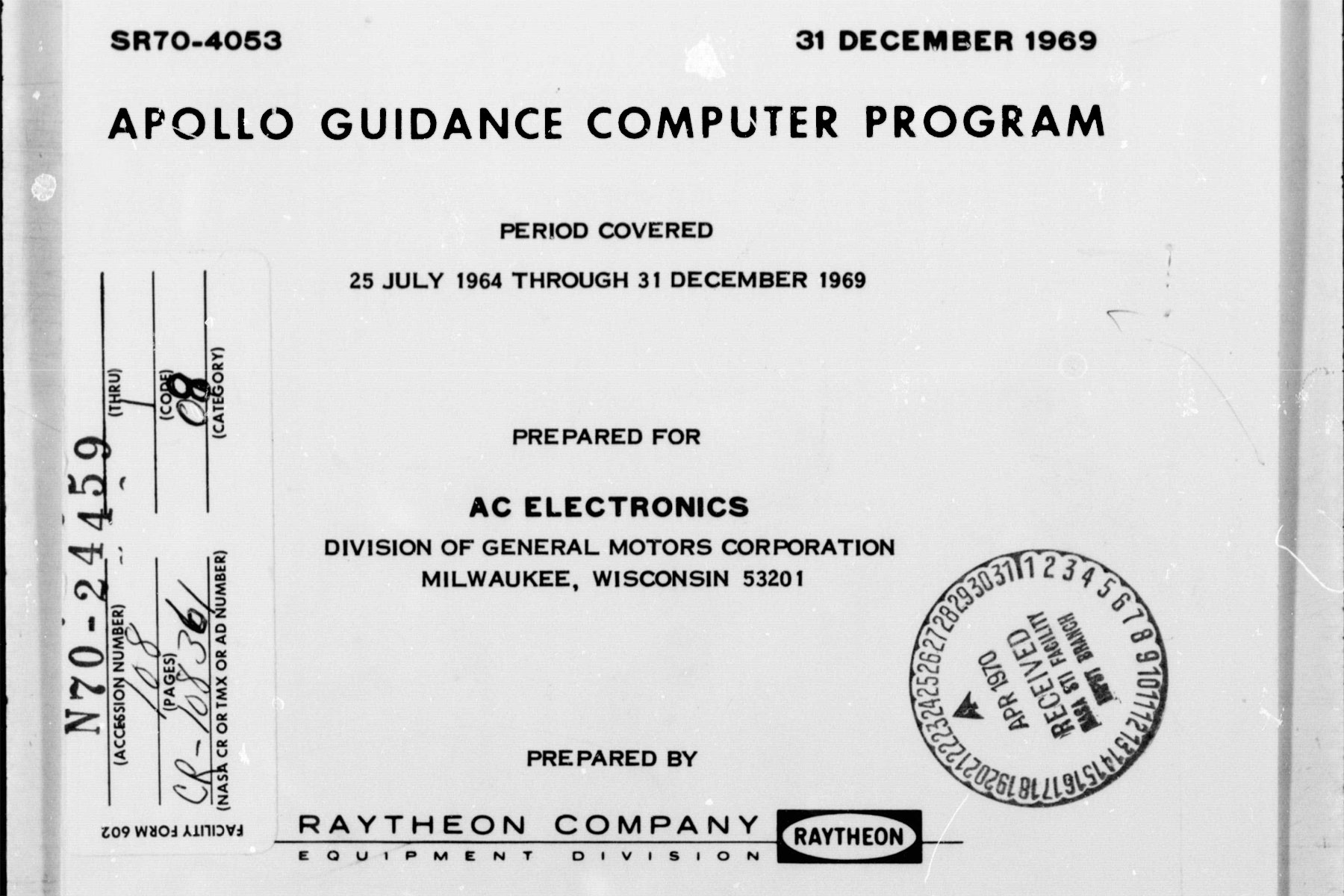

Over time the company’s operational divisions were separated, sold, and evolved. In 1965, the Milwaukee Operations became known as AC Electronics Division of GM. It was an integral part of the success of NASA’s Manned Space Program program, competing against the Soviet Union in the race to space.

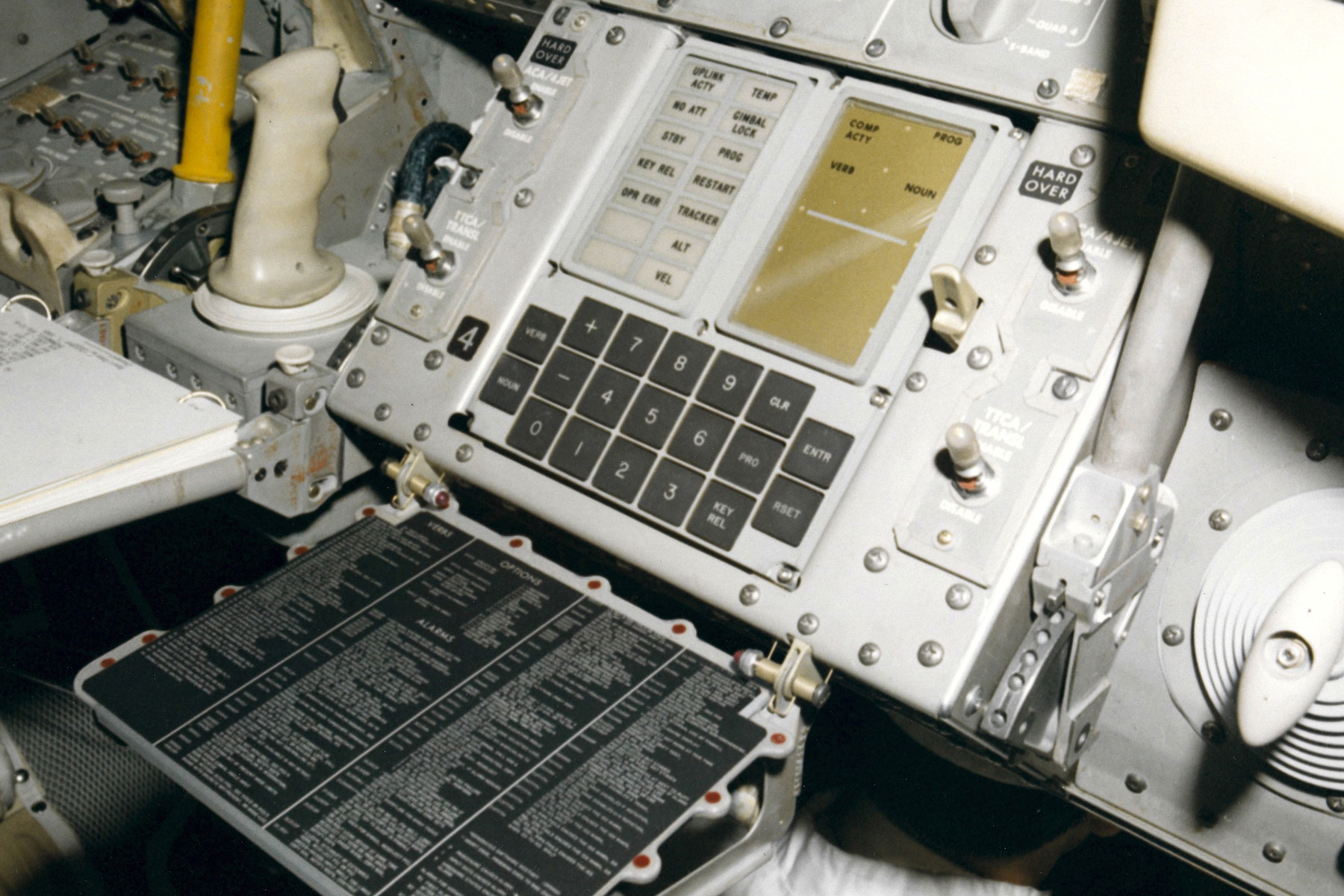

AC navigation-guidance systems were used by NASA to steer the Apollo spacecrafts in earth and lunar orbits, lunar landings, and return flights to a predetermined point on earth.

In 1970, the division merged with Delco Radio and became known as Delco Electronics Division. Delco’s Lunar Roving Vehicle first traveled on the surface of the moon in 1971 as part of the Apollo 15 mission, allowing astronauts to cover a larger area than all prior lunar landing missions.

David Pierini, a technology writer and photographer, recalled a special connection to Milwaukee and memories of the NASA space program.

I had the kind of dad who brought his work home with him. That was exciting since he was in the business of putting men on the moon. Each time there was a scheduled launch, my two brothers and I could always expect our dad to come home with mission patches.

Robert Pierini was an engineer in the late 1960s and early 1970s with an electronics company in Milwaukee that developed the guidance system for the Apollo mission.

So when filmmaker Neil F. Smith recently posted a video to YouTube, bringing animated life to each mission emblem, I immediately felt the same rush I had as a kid when I held a patch in my hand.

I was too young to remember the first few, including Apollo 11, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk the lunar surface. But my memories picked up for the missions after. Like most living rooms, the launches were big television events narrated by trusted CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite.

It was an exciting time in America. It was a stage of the Space Race where we felt like NASA was pulling ahead of the pioneering Soviets, our Cold War enemy. And then to have someone in the house who was a part of the unfolding history was an electrifying source of pride.

The patches were colorful and cool. Every once in a while, dad would bring home a gauge or a lever from a control panel that we were allowed to touch – carefully. We boys would get a patch, while it was tradition for my father to give my mother a charm for a bracelet marking missions dating back to the first Gemini.

There were pins and tie tacks, including an Apollo 11 tie bar with the words “Mission Team.” I wore it on my wedding day.

There would be trips to “the Cape,” the way he referred to Cape Canaveral, and snapshots he took of the Saturn V rocket being positioned on the launch pad. I wish I could find the photograph of him from the Launch Control Center wearing a white hard hat, his work badge showing, dorky glasses that now seem hipster-chic and the launch umbilical tower in the background.

Soon after Armstrong and Aldrin, America lost interest in the moon and my dad was laid off in 1973. He could have collected unemployment, but he was too proud, instead taking odd jobs like teaching drafting at a local community college. He eventually found work for a company that made diesel engines, but this brought no excitement to him or our house.

Occasionally, often at my pleading, he would bring out a film projector and show 8 mm films from the different space missions. There was no sound, so my dad would excitedly color commentate some detail to which he had been privy. He would sometimes grow quiet during these films, the only sound being the projector’s motor, and I could sense he was feeling a longing for work that had that same purpose.

Related to the NASA mission patches, in 2015 the Smithsonian launched its first-ever crowdfunding campaign in an effort to preserve, conserve, and display the spacesuit that Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong wore while becoming the first man to walk on the moon.

With an original goal of $500,000 the Kickstarter campaign has remained ongoing, with a revised aim to reach $700,000. Called “Reboot the Suit,” the initiative’s purpose was to digitize and exhibit Armstrong’s spacesuit at the National Air and Space Museum in time for the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing mission in 2019. It will then go on permanent exhibit as a centerpiece in the new “Destination Moon” gallery, scheduled to open in 2020.