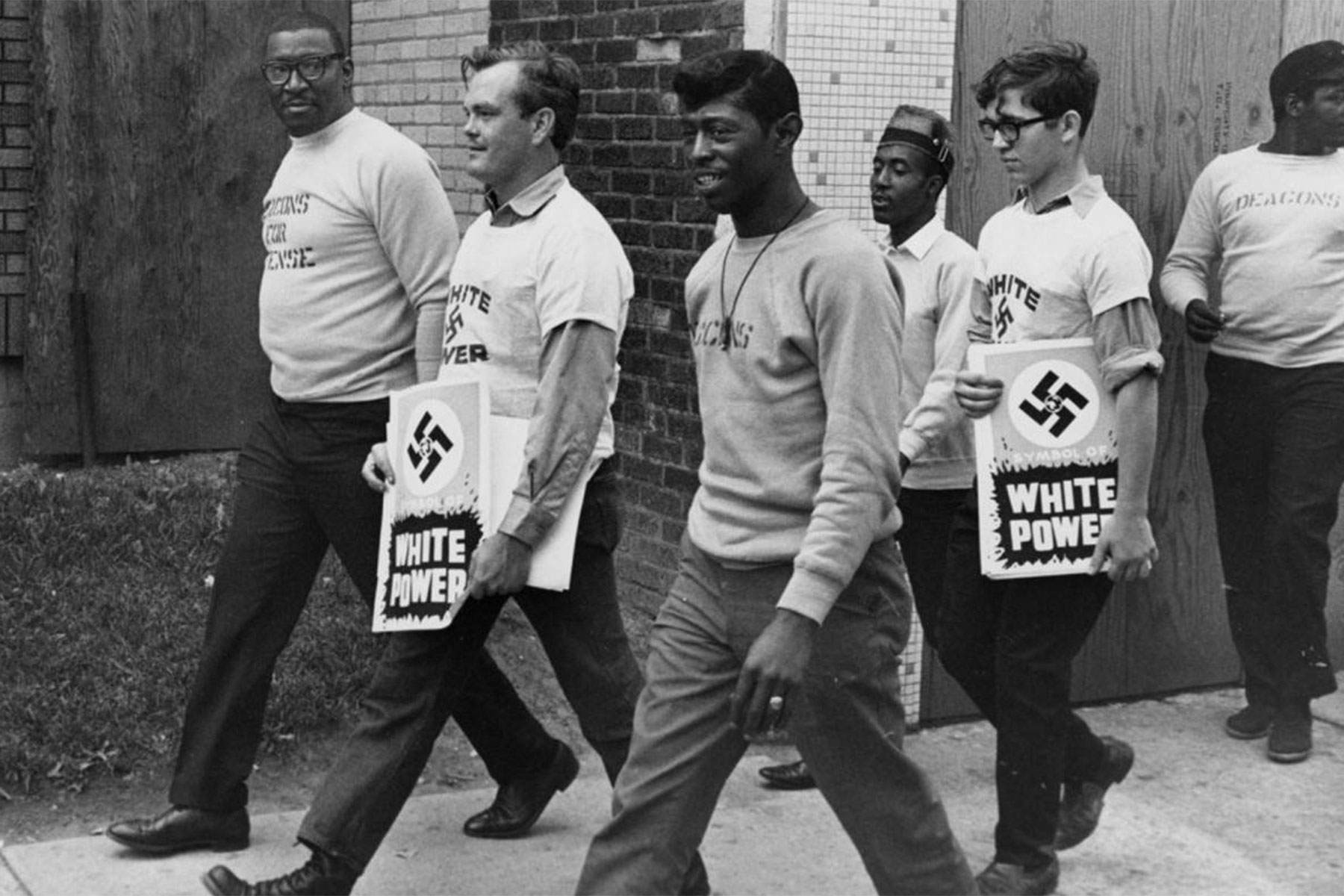

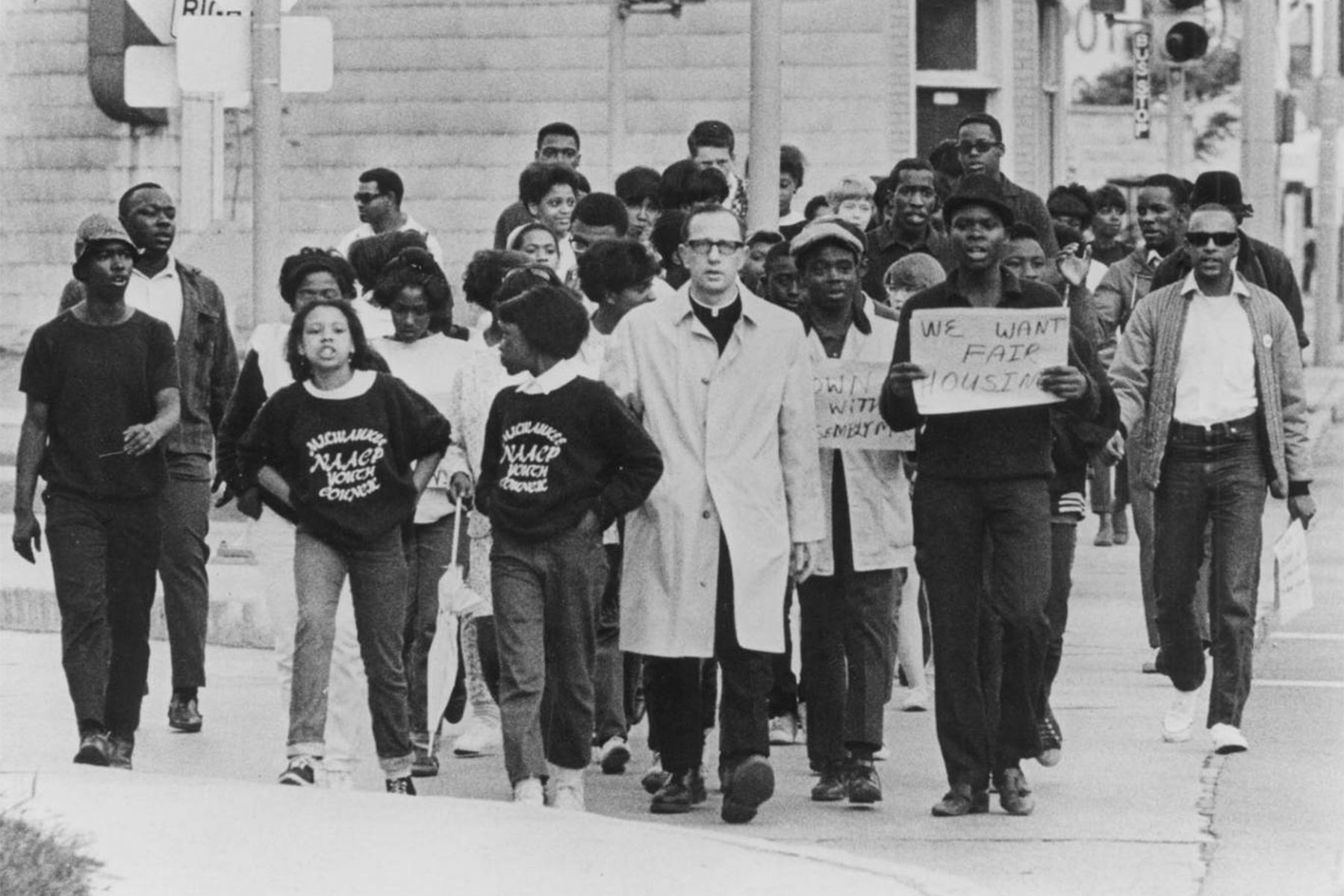

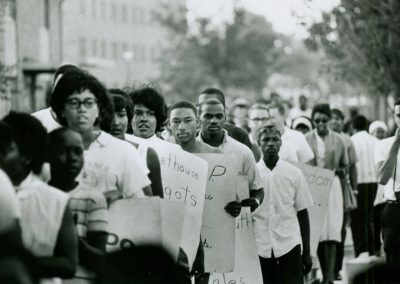

Early in the evening of Monday, August 28, 1967, over one hundred members of the Milwaukee Youth Council of the NAACP gathered at their headquarters at 1316 North 15th Street, picked up signs hand-lettered with slogans like “We Need Fair Housing,” and, led by Father James E. Groppi, a white Roman Catholic priest who served as their adviser, headed toward the 16th Street viaduct. At about 6:30 p.m. they were greeted at the north end of the viaduct by almost another one hundred supporters and crossed over the viaduct to the nearly all-white south side of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There the marchers met resistance. [1]

On the southeast corner of South 16th Street and West National Avenue, young white men sat on the hoods of cars at Crazy Jim’s Motors, holding other signs including one that read “Groppi—the Black god.” In fact, as many as 8,000 people, according to Milwaukee Police estimates, lined the route on South 16th Street and then along West Lincoln Avenue east to Kosciusko Park. These counter-demonstrators jeered, taunted, and cursed the young open housing marchers. [2] What caused this confrontation? And what were the results?

Answering those questions involves stepping back away from the viaduct to look at issues and events that brought 1967 Milwaukee to this brink. Mention the 1960s and most audiences think in terms of multiple branches of activity, including anti-Vietnam war protests, student unrest, and a youth counterculture, all stemming from and following the civil rights movement. In this view, the civil rights movement came into the national picture with two prominent events. The first is the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kаnsаs. This ruling overturned the doctrine of separate but equal, the standard in public education and accommodation for over fifty years, since the Supreme Court had issued it in 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson.

The second event credited with initiating the modern civil rights movement is the 1955-1956 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott. Begun after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white person, the boycott of the bus system by Montgomery’s African American community resulted in a Supreme Court ruling to end bus segregation in Montgomery.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who emerged as a leader in the Montgomery boycott, went on to become the foremost spokesman for the civil rights movement, and, as the subsequent years have compressed many events into a single image, Dr. King has become the icon that signifies the civil rights movement. Many histories of the movement end with the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March and the subsequent passage of the Voting Rights Bill of 1965, signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, August 6, 1965. [3]

In danger of being forgotten are civil rights movements after 1965, especially those in the North. Dr. King himself went to Chicago in 1965 and 1966 to tackle issues of de facto segregation. The Chicago freedom movement focused on the issue of fair, or open, housing; that is, the right of citizens to rent or own property wherever they choose, regardless of race, color, or creed. The goal of Dr. King’s march into the all-white Chicago suburb of Cicero was to develop momentum for legislation to establish and safeguard this right. [4] While the campaign in Cicero may not have reached its goal, it helped to inspire and energize local movements in the North. [5]

By the early 1960s in Milwaukee, the energy of national civil rights movements had already taken hold. A local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had worked on issues of public accommodations and insensitive remarks made by public officials. The Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC), led by Wisconsin Assemblyman Lloyd Barbee, protested discriminatory policies of the Milwaukee School Board and organized school boycotts. The Milwaukee Youth Council of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), led by Father James Groppi, had marched at the homes of judges who maintained memberships in the Fraternal Order of Eagles, which had a “whites only” membership policy. [6]

African Americans faced a housing crunch in Milwaukee in the 1960s. Not only was the African American population of the city increasing, but available housing was also being reduced due to urban renewal projects that included tearing down old housing units. Often when African Americans moved beyond the confines of existing black neighborhoods, they were met with hostility. More often, when they tried to rent or buy in such neighborhoods, they were turned down altogether. [7]

In 1962, Alderman Vel R. Phillips, the first African American and the first woman elected to the city of Milwaukee Common Council, was also the first to introduce an open housing ordinance. Hers was the sole vote in favor; thus, her proposed legislation was voted down. Each time she re-introduced the legislation, the results were the same.

Late in 1966, Ronald and Norma Britton were told by the white owner of a duplex that she couldn’t rent to them because “what would my neighbors think?” Knowing of the activist orientation of the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, Ronald Britton, an ex-Marine recently returned from Vietnam, called Youth Council adviser, Father James E. Groppi of St. Boniface Church on 11th and Clarke Streets in Milwaukee’s inner core, as the largely African American central city was then known. Father Groppi brought the issue to the Youth Council who took action to support this Vietnam veteran and his family. With the Christmas holiday approaching, members of the Youth Council and Father Groppi went to sing Christmas carols to the landlady. [8] Father Groppi also telephoned Alderman Vel Phillips to ask if she’d like the support of the Youth Council in her efforts to get a fair housing ordinance in the city of Milwaukee. Discouraged in what for her had been a lonely battle, she welcomed their support. [9]

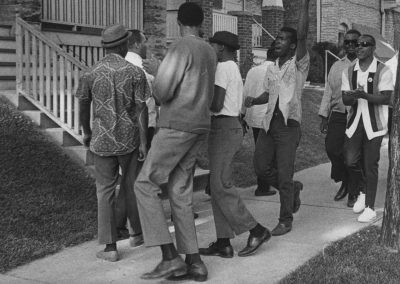

The Youth Council’s first step to increase pressure on the Common Council was to picket at the offices and homes of aldermen who had black constituents but who were voting against the fair housing ordinance. Among the first targets was the home of Common Council president Martin Schreiber Sr. where the Youth Council and Father Groppi picketed June 19, 1967. During that demonstration, when Youth Council president Fred Bronson and several other Youth Council members rang the doorbell, Schreiber invited them in to talk, but no agreement was reached. In the next four weeks, the Youth Council picketed at the Capitol Drive office and nearby home of Alderman James Maslowski, who, because the alderman position was officially designated as part-time, continued to work as a real estate agent. Tuesday, July 18, 1967, the Youth Council went to the home of Alderman Robert J. Dwyer, where Dwyer’s daughter reported that her father was not home. [10] When Father Groppi and the Youth Council returned the next night, Dwyer met with Youth Council president Fred Bronson. After their meeting, Bronson told reporters that “the time spent with Dwyer was wasted.” [11]

Later that week the Youth Council picketed several times at the home of Alderman Eugene Woehrer, who lived at 600 East Burleigh Street and represented a district with a sizable black constituency. The picket lines started small, no more than two dozen people. As the picketing continued, it gained momentum as the Youth Council marched for several blocks around the Woehrer neighborhood, upsetting some neighbors while others joined in the line. By the end of the week, according to newspaper reports, one hundred people were on the picket line.

The Youth Council and their supporters filled the Common Council Chambers for a meeting July 25, 1967. Alderman Vel Phillips moved to alter the usual meeting procedure in order to allow Father Groppi to speak on central city issues, particularly the need for open housing. Her motion generated considerable debate with several aldermen who objected to this unusual move to allow someone other than an alderman to speak at a Common Council meeting. Alderman Norman Hundt brought the debate to a close by noting that the Council was spending more time arguing about whether Father Groppi should talk than he’d take talking. “Whether we agree with him or not, I don’t think we are too busy to listen to him.” [12]

Father Groppi argued that due to the critical housing needs in the inner city and the lack of response from public officials, tempers were rising. He warned of the likelihood of rioting in Milwaukee since peaceful means of redressing grievances met with resistance rather than success. South side Alderman Robert Anderson was among those who questioned Groppi. He asked, “Who’s behind this? Why doesn’t the clergy tell their people to come out for open housing?” Father Groppi replied, “Alderman Anderson, for once we agree on something. But that does not excuse your inactivity.” [13]

Several days later, Anderson telephoned the office of Archbishop William E. Cousins, demanding that Groppi be sent to Panama. According to news reports, “Anderson’s shouts could be heard throughout the city clerk’s and aldermen’s offices on the second floor of city hall and drew a crowd of aldermen and other onlookers.” When a reporter from one of the city’s radio and TV stations approached Anderson with a microphone, “the alderman tore it from its cord.” [14]

The potential for rioting that Father Groppi had warned about soon became reality. July 30, 1967, police patrolling Third Street, a main thoroughfare in the African American community, tried breaking up a crowd of black teenagers after they left a dance, but when the situation escalated, the police notified the mayor. Mayor Maier soon put the contingency plan he had developed into action. He called Governor Warren Knowles for National Guard assistance and declared a curfew that stayed in effect until August 9. Given these conditions, Father Groppi and the Youth Council temporarily suspended their campaign for a fair housing law.

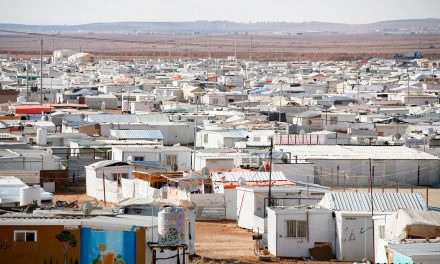

After the curfews ended and the National Guard returned home, the open housing campaign soon moved into its second phase. On August 23, 1967, NAACP Youth Council Commandoes Prentice McKinney and Dwight Benning announced to the press that the Youth Council would take its message city wide. [15] Specifically, the Youth Council Commandoes, the direct action committee that had also become the strategy-planning unit for the Youth Council, would lead a march across the Menomonee River Valley to the south side. The Menomonee River Valley was called Milwaukee’s “Mason-Dixon line,” the dividing line between the black and the white communities. In fact, an old joke in Milwaukee about the Sixteenth Street viaduct, one of the bridges that span the valley, highlights the point: What’s the longest bridge in the world? The 16th Street viaduct—it connects Africa and Poland.

On Monday, August 28, 1967, more than one hundred Youth Council members and supporters, flanked by Youth Council Commandos, proceeded from the 15th Street Freedom House to the 16th Street viaduct. At the north end of the viaduct stood a contingent of members from St. Veronica parish on the far south side, Alderman Anderson’s territory, but also the place where Father Groppi had been assigned fresh from ordination. They held signs reading “We South Siders Welcome Negroes.” Theirs were the last friendly faces the Youth Council met. [16]

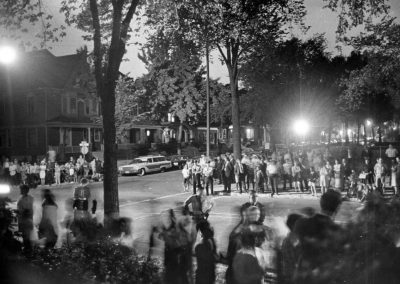

At the south end of the viaduct, crowds of counter-demonstrators were being held back from the marchers by a line of Milwaukee police officers. The marchers were able to move past them, and past those sitting on used cars in the lot at Crazy Jim Motors. Then they advanced to the Kosciuszko Park picnic area for which they had a picnic permit.

At the park, the Youth Council huddled around several picnic tables. Father Groppi stood on top of a picnic table so that the marchers could see and hear him. A district park supervisor interrupted him, shouting that a picnic permit did not permit speeches. Father Groppi replied, “We want our picnic area. When you enforce the law on them,” gesturing toward the 5,000 counter-demonstrators surging just beyond the picnic area, “you can enforce it on us.” [17] Urged by police to return to the north side quickly before the hostile crowds could break through police lines, Father Groppi led the Youth Council in a short prayer, and then they began the three mile march back to the north end of the viaduct.

On 16th Street, as the marchers approached the south end of the viaduct, they were met by a crowd that hurled a barrage of rocks, bottles, and garbage at them, and those who carried picket signs held them over their heads for protection. At times the marchers, especially those at the back of the line, had to run. Television camera crews holding heavy film cameras ran alongside. As the line of marchers made its way back to the north side, Father Groppi labeled the actions of the unruly counter-demonstrators on the south side a “White riot.”

In his unpublished autobiography, Groppi remembered that he tried to telephone Mayor Henry Maier to urge him to call for the National Guard to reinforce the Milwaukee Police, the same strategy that the mayor had implemented during the north side riot. Fair and equal treatment demanded the same response to white rioting as to black rioting. The rights of the marchers to assemble and to speak for their cause, he said, were in jeopardy. The city needed the presence of the National Guard at this point even more than before. Groppi also tried to call Governor Knowles, whose office said, “We cannot send the National Guard out for just anything.” Knowles, who was out of the state at the time, told the newspapers that he had offered the National Guard to Maier if he wanted it, but the mayor did not accept the governor’s offer. [18]

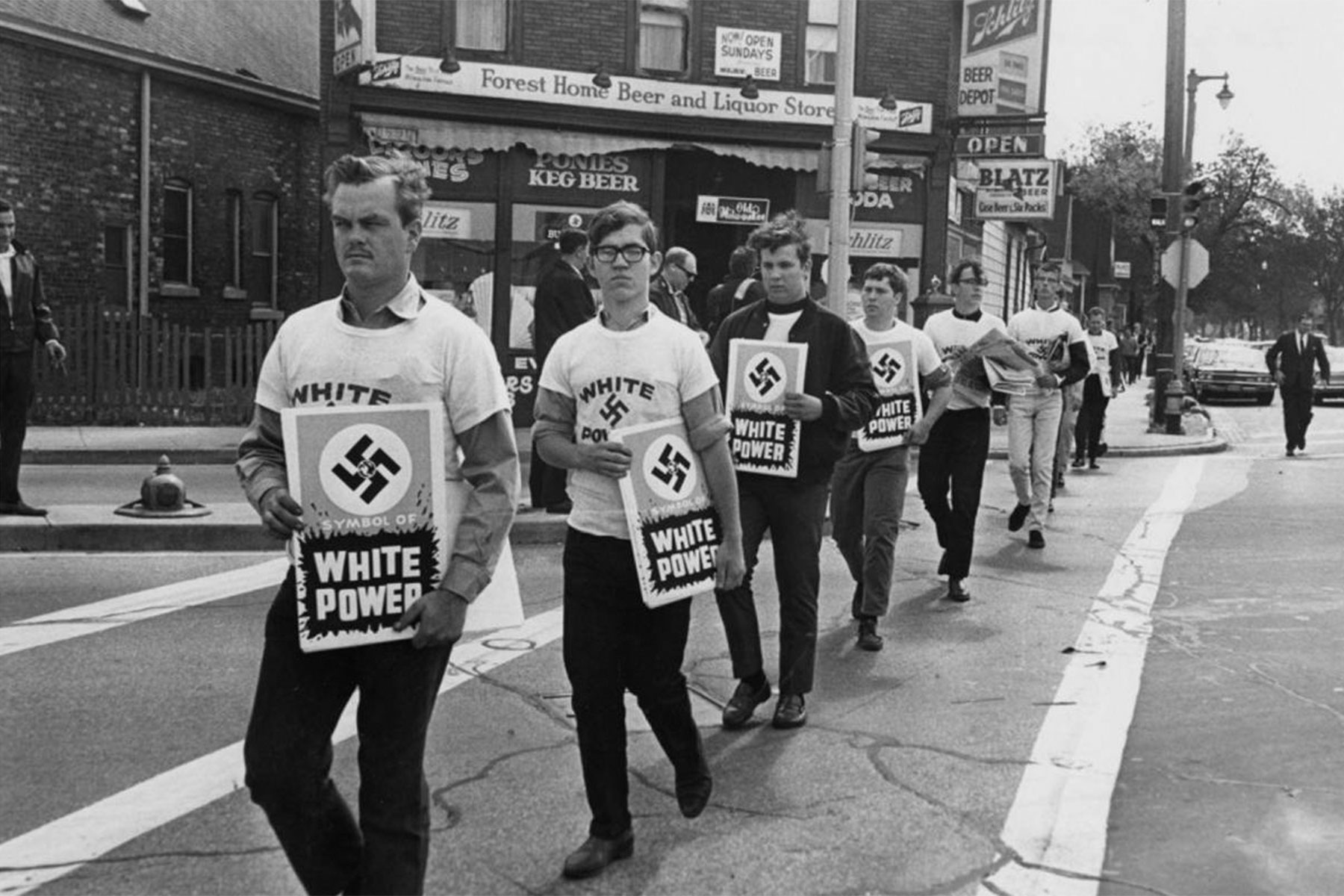

On Tuesday, August 29, the night of the second march, crowds on both sides swelled. Almost 13,000 counter-demonstrators, according to a Milwaukee Sentinel estimate, lined the south side route of the march. Youths among the counter-demonstrators chanted “E-I-E-I-E-I-O. Father Groppi’s got to go.” According to Milwaukee Sentinel reporter Bernice Buresh, some shouted kill… kill… kill. “That word was shouted over and over again Tuesday night by white teenagers and white children—some no older than 7 or 8 years—as they ran alongside the civil rights picket line.” At another point, Buresh saw a small boy, about three years old “wearing a white sweatshirt on which was lettered in black paint, ‘Go Home, Nіggеr.’” [19]

The police used tear gas to disperse the counter-demonstrators. In his book City With a Chance, Milwaukee Journal civil-rights reporter Frank Aukofer summarized what he saw that night: “By the time the marchers reached the safety of the viaduct, they looked like refugees from a battle. They were dazed and bewildered, some still suffering from the effects of tear gas that had hung in the air. Some could not walk and had to be carried by other marchers. Blood streamed down the face of a young white seminarian who had been hit by a bottle. [20]

On that night there was to be no respite when the NAACP Youth Council members and their supporters returned to the North 15th Street Freedom House. Police reported sniper activity in the area and cordoned off nearby streets. They patrolled in front of the Freedom House with shotguns and, trying to disperse the crowd, fired tear gas into the Freedom House. The house burst into flames. Those inside scrambled out. The crowds outside pushed backward toward the street. Flames engulfed the house, but the fire department was nowhere to be seen. Later fire chiefs reported difficulties getting to the scene since key thoroughfares were still closed. Before the night was over, all that was left of the 15th Street Freedom House was a charred and crumbling frame. [21]

In the next three days, the situation deteriorated even further. Mayor Henry Maier issued a proclamation forbidding all night-time marches for the next 30 days. Father Groppi and the Youth Council had learned a year earlier during their campaign against the membership of public officials in the all-white Eagles Club that all their work of organizing and building momentum could be undone through such official cooling off periods. Nevertheless, they decided to call off the march for Wednesday, August 30. They gathered instead at their burned out headquarters to meet those who hadn’t gotten the word of the cancellation and to rally on the Freedom House property for open housing. Alderman Phillips, who had introduced a fair housing ordinance in the Common Council multiple times, joined them.

Police declared the assembly unlawful and arrested over fifty people. These arrests prompted Father Groppi and the Youth Council Commandos to reverse their strategy. If they were going to be arrested even when they didn’t march, they may as well march. On August 31, the crowds outside of St. Boniface church, 2609 North 11th Street, struggled to make their way inside the church that was filled to overflowing. Dramatic newspaper photos of the freedom house on fire and stories about the arrests of the night before brought an outpouring of support. People of all ages from throughout the neighborhood and the entire city gathered ready for the next step. They followed Father Groppi, the Commandos, and other Youth Council members from the church, south on 11th Street toward North Avenue, heading downtown to city hall where they wanted to see the Mayor. At about 9th and North Avenue, the police moved in and first arrested Father Groppi and Alderman Phillips, and then filled the waiting patrol wagons with other marchers.

The next day the Milwaukee Journal reported that 117 adults and 17 juveniles had been arrested during the demonstration. Most were charged with violating the mayor’s proclamation and had paid $25 bail. Alderman Vel Phillips was released without bail. In addition to the charge of violating the mayor’s proclamation, Father Groppi was charged with resisting arrest and battery and obstructing an officer. In the trial of this case, the question of whether a defendant was entitled to a change of venue in a misdemeanor trial became central. Father Groppi was denied a change of venue by the lower courts. Eventually he won the point in the U.S. Supreme Court. But this time, County Judge Christ Seraphim set Father Groppi’s bail at $1000, calling Groppi a ‘repeater,’ and asserting his belief that “the public has a right to be protected from a repeater. You have to deal with crime as you would with a disease. You have to isolate it.” [22] National news media rushed to cover the Milwaukee demonstrations following these mass arrests. Thus the Milwaukee Open Housing Movement entered a third phase, that of a national movement.

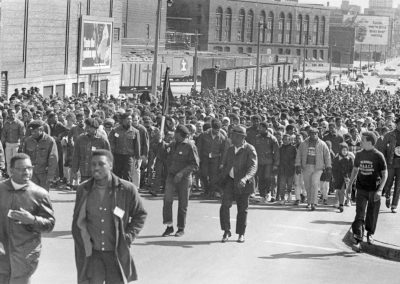

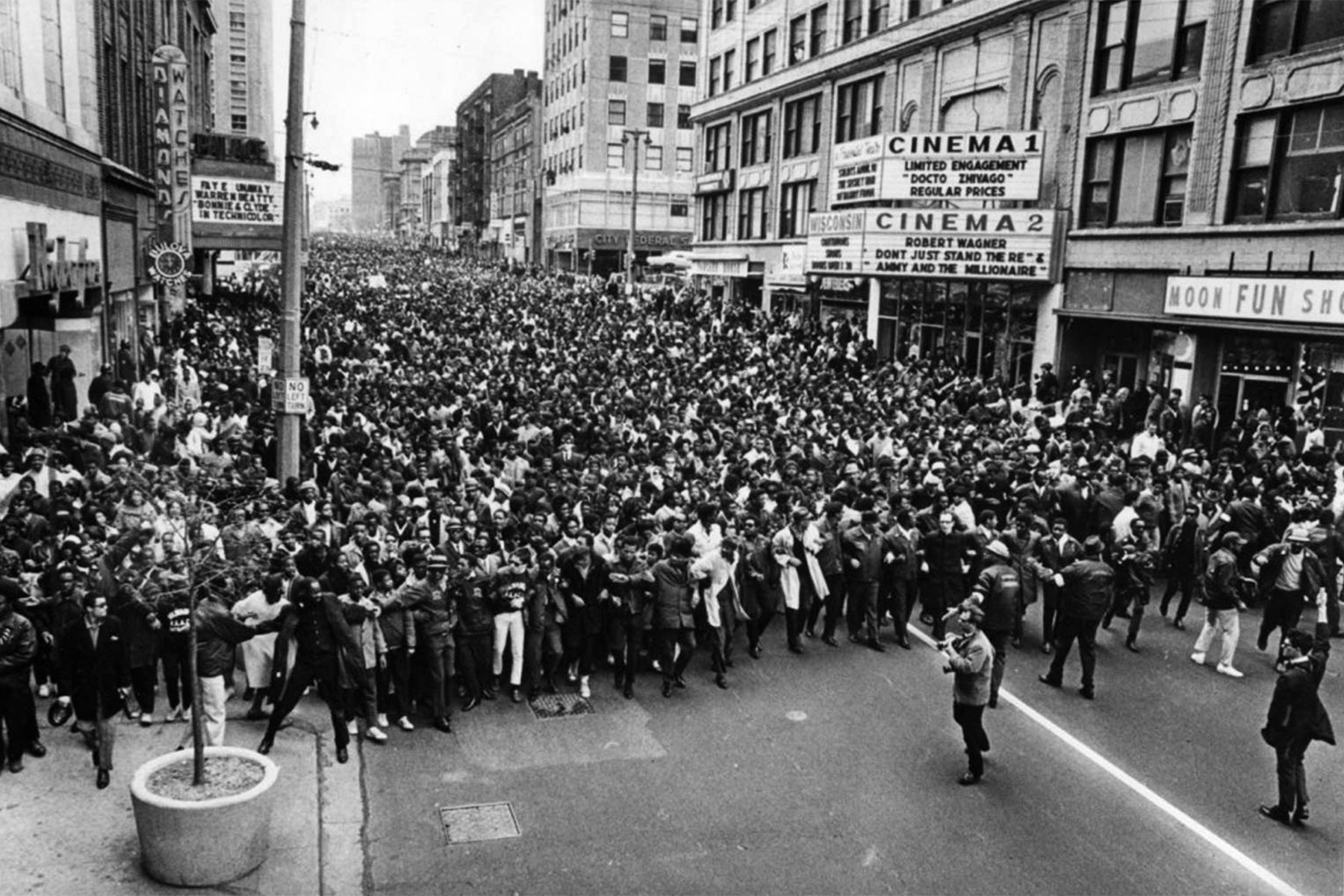

The NAACP immediately dispatched reinforcements to Milwaukee, including regional field director Sydney Finley, who was arrested with Father Groppi the next night, and regional youth director William Hardy. National Youth Director Mark Rosenman arrived the following day. The NAACP also put out a call to its other branches to join the Milwaukee Youth Council in marching the next weekend. As a result, the march September 10, 1967, drew over 5,000 supporters of fair housing, the largest march to date in Milwaukee. [23] Sam Dennis, an agent with the U.S. Department of Justice, was also with Father Groppi the night of the rally at the burned out Freedom House. [24]

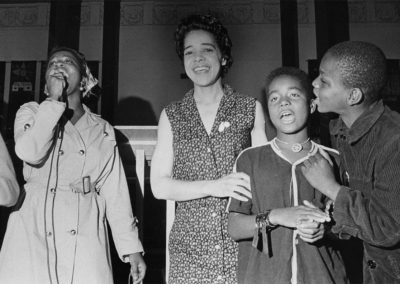

Letters of support came from longtime civil rights activists, including the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Nashville, Tennessee, whose church was a headquarters for the students who initiated the lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville and who later became the founders of the Student Non-Violent Coordination Committee. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King sent a telegram that included these words of support: “What you and your courageous associates are doing in Milwaukee will certainly serve as a kind of massive nonviolence that we need in this turbulent period. You are demonstrating that it is possible to be militant and powerful without destroying life or property. Please know that you have my support and my prayers.” [25]

Comedian and activist Dick Gregory, among the first to join in the Milwaukee movement, made repeat trips to the city to march for open housing and became part of the team that planned strategy. Among his suggestions were ideas for economic boycotts to put pressure on city officials. The first of these was a boycott of Schlitz, whose advertising slogan was “The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous.” Another Dick Gregory idea was to celebrate Christmas 1967 as a “Black Christmas,” one that involved family and community celebrations rather than buying gifts, thus initiating an economic boycott of city merchants during their key Christmas sales season. [26]

Because of the publicity, many colleges, universities, television talk shows, and other civil rights groups bombarded Father Groppi with invitations to give public lectures. Some of these he accepted, for example, the Kup’s Show on WBBM-TV in Chicago where he appeared with singer Harry Belafonte. Others he referred to some of the more experienced Youth Council members. One letter from a supporter in Minnesota describes a conversation with Milwaukee Youth Council member Robert (Curley) Walston after Walston spoke there. He had been asked what he thought of Father Groppi. Curley replied, “I love the quicksand he walks on.” [27]

Father Groppi was invited to speak before the National Advisory Committee on Civil Disorders. Accompanying him were Commandos Dwight Benning and James Pierce. After recounting some of the events of the Milwaukee demonstrations, Father Groppi concluded:

[I]n Milwaukee we have the last test demonstrations of a nonviolent tactic. H. Rap Brown I see in East St. Louis told people to stop singing and stop marching, stop demonstrating, and go home and get a gun, and his reason for saying this is simply he has lost faith in marching and in demonstrating.

This is a constructive way of social protest. The grievances and the anger of the black community are not only justified but this anger is good. It is a sign of life. It has to be channeled into a constructive pattern of social action. [28]

Father Groppi believed that the open housing demonstrations in Milwaukee provided a constructive pattern for the NAACP Youth Council members and Commandos to express their grievances in a way that minimized random violence. On only one occasion did an open housing demonstration involve damage done by Youth Council members; this was in the mayor’s office September 7, 1967. [29]

International publicity for Father Groppi also ensued. A letter from Ed Hayes, a white priest at Nyamwaga Catholic Church in Tanzania makes this point:

Dear Father Groppi, I’ve been hearing about your work on the Voice of America and, as another white priest with a black heart, I just want to thank you and to assure you that you and your people are in my prayers these days… So now that a white Catholic priest has stood up with our black brothers in America, our presence and our message has been made more acceptable. I thought it might encourage you to know that your work and your love is having in some small way, an effect in spreading the message of Christ here in Africa. So keep up the good work and don’t get discouraged—I seem to recall that Jesus, too, was accused of being a rabble-rouser. And please offer some of your sweat and tears for your brothers in Africa. [30]

As 1967 drew to a close, the Associated Press voted Father Groppi “Religious Newsmaker of the Year.” [31] Locally, the Priest Senate of the Milwaukee Roman Catholic Archdiocese urged the “immediate passage of a city ordinance for open occupancy thereby making the city of Milwaukee the moral leader necessary at this time to facilitate a country wide open occupancy bill and a more effective state open occupancy bill.” [32] Three Lutheran district presidents, Dr. Myron C. Austinson of the American Lutheran Church, Pastor Theodore E. Matson of the Lutheran Church of America, and Pastor Herbert W. Baxmann of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, issued a statement declaring that “Christian citizens should support such legislation as well as help to guarantee human rights to all persons in our community, state, and nation.” [33]

Despite focus of attention on the issue that included: the statements of religious leaders; the accolades Father Groppi and the Milwaukee Youth Council earned nationally; and the ongoing nightly marches in Milwaukee where clashes with police and/or with counter-demonstrators continued to be a factor in the life of the city; the Milwaukee Common Council would go no further than to pass a bill that duplicated an already existing state fair housing law that, in effect, exempted most rental units. [34]

But the issue had been picked up in the national press. Senators Edward Brooke of Massachusetts and Walter Mondale of Minnesota urged inclusion of a strong fair housing provision as the Senate debated new civil rights legislation in February 1968. Senator Mondale referred specifically to Father Groppi and the Milwaukee marchers as he argued for a three-phase process in the law that would eventually cover most housing units throughout the country. [35] Senator Mondale wrote to Father Groppi, saying “Your contribution to this effort, whether we are defeated or are successful, has been most significant, and I do appreciate it.” [36] Unfortunately Congress was slow to move. On March 30, 1968, following 200 continuous nights of marching, the Milwaukee Youth of the NAACP announced it was ending the marches, vowing to continue working on the issue in other ways, though no specific strategies were announced. [37] It was a period for questioning: what would work?

Then, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was shot and killed. Outraged black communities erupted in violence. In Milwaukee, the Youth Council Commandos and Father Groppi decided to respond to King’s death in a way that honored the nonviolent philosophy of Dr. King. They organized a march through downtown Milwaukee to a rally on the north side. Over 15,000 people joined in that march, the largest in the city’s history and one of the nation’s largest memorial demonstrations for Martin Luther King. [38]

Feeling the urgency of the nation’s mood, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included strong open housing provisions, and on April 11, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed it. [39] Finally, on April 30, after 200 nights of marching, the death of Dr. King, new elections in the city of Milwaukee, and the passage of the federal law, Milwaukee followed suit. The Common Council passed a citywide open housing ordinance, one that went even further than the federal law. [40] The long Milwaukee campaign for fair housing thus reached its successful conclusion.

Almost a dozen years later, a retrospective article in the Milwaukee Journal noted “Although Milwaukee experienced civil rights activity throughout much of the quarter century since the Brown decision, it became the object of national attention only after a white Catholic priest rose to a leadership position. There were those who said that the prominence accorded to the demonstrations led by Father James E. Groppi was, in itself, evidence of the racism that existed in society. Regardless of the underpinnings, the Groppi Years were what made Milwaukee famous in the Civil Rights Movement.” [41] Today the Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council continues the work of monitoring compliance with the open housing laws, the product of hard-won victories.

[1] Editorial note: Author Margaret Rozga, Fr. Groppi’s widow, was an active participant in the marches on Milwaukee and was a witness to the events documented in this article. Some statements in the article that are not attributed to primary sources are her personal recollections of these events.

[2] See the Milwaukee Sentinel and the Milwaukee Journal, August 29, 1967, for accounts of these events.

[3] An excellent analysis of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his participation in the civil rights movement is David. J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York: William Morrow, 1986), see chapter 2 for the Montgomery bus boycott and see chapters 7 and 8 for the Voting Rights Bill; See also Raymond D’Angelo, ed., The American Civil Rights Movement: Readings and Interpretations (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001).

[4] See Garrow, chapters 8 and 9.

[5] For information on Northern, locally-based civil rights movements, see Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, eds., Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America, (New York: NYU Press, 2005).

[6] Frank Aukofer, City With a Chance, chapters 5 and 6. (Milwaukee, WI: Bruce Publishing, 1968).

[7] Author interview with Ronald Britton, February 6, 2007, and author interview with Vel Phillips, January 24, 2007. Also see, “Some Negroes Can Flee, But Core Holds Onto Most,” Milwaukee Journal, July 7, 1967.

[8] Author interview with Ronald Britton, February 6, 2007; Homily by Father James Groppi published in Community: Monthly Magazine published by Friendship House, November 1967. James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 14, folder 2.

[9] Author interview with Vel Phillips, January 24, 2007.

[10] For accounts of the events of this and the next paragraph, see the Milwaukee Sentinel and the Milwaukee Journal July 18, 1967, to July 24, 1967, and Aukofer, 106-108.

[11] Milwaukee Journal, July 20, 1967.

[12] Ibid., July 26, 1967.

[13] Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel, July 24, 1967. see also March on Milwaukee. (New York: NAACP Youth and College Division, 1967), 1-2, in James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI, M2001-085, Box 1, Folder 38.

[14] Milwaukee Sentinel, July 29, 1967.

[15] Milwaukee Journal, August 24, 1967; see also March on Milwaukee. (New York: NAACP Youth and College Division, 1967), 1-2, in James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI, M2001-085, Box 1, Folder 38.

[16] For several accounts of the events of August 28 through August 31, 1967, see the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel August 29, 1967, to September 2, 1967: Aukofer 109-121: Father Groppi’s testimony before the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 15, Folder 5, and the James Groppi unpublished autobiography, James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI, accession M2001-085, Box 4, Folder 20, 87-88. Some minor details are from the author’s recollections of the events.

[17] Aukofer, 111.

[18] James Groppi unpublished autobiography, James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI, accession M2001-085, Box 4, Folder 20, 87-88; Milwaukee Journal August 29, 1967.

[19] Milwaukee Sentinel August 30, 1967.

[20] Aukofer, 116.

[21] Father Groppi stated in the newspapers and his autobiography that the fire was started by a tear gas canister thrown by the police, white the official police version, reported in the Milwaukee Journal and the Milwaukee Sentinel August 30, 1967, states that an unidentified person threw a firebomb through the window from a car and drove away.

[22] Milwaukee Sentinel September 1, 1967.

[23] March on Milwaukee in James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI, M2001-085, Box 1, Folder 38.

[24] Groppi’s testimony to the National Advisory Commission of Civil Disorders. James Groppi Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

[25] Telegraph from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Father Groppi, September 4, 1967, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 2, Folder 3 (original was not punctuated).

[26] Aukofer, 131-132, 134.

[27] J. Millard Ahlstrom letter, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 12, Folder 5.

[28] Groppi testimony before the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. James Groppi Papers, Box 15, Folder 5.

[29] Aukofer, 123.

[30] Ed Hayes Letter, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 4 Folder 1.

[31] Note and undated clipping sent by Frank Aukofer, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 15, Folder 2.

[32] From the minutes of a Priest Senate meeting, signed September 8, 1967 by Dennis C. Klemme, Secretary of the Priest Senate, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 15 Folder 1.

[33] Quoted in The Lutheran Standard December 26, 1967, clipping sent by Frank Aukofer, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX, Box 15, Folder 2.

[34] Aukofer, 133.

[35] Congressional Record, February, 6, 1968

[36] Walter Mondale Letter, James Groppi Papers, Milwaukee Area Resource Center, Wisconsin Historical Society, Manuscript EX. Box 4, Folder 5.

[37] Milwaukee Journal, March 13, 1968.

[38] Aukofer, 142.

[39] For more information of this law, see the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s website, http://www.hud.gov/offices/fheo/progdesc/title8.cfm.

[40] Aukofer, 143.

[41] Milwaukee Journal, May 13, 1967.

This essay was originally published in the Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 28-39. It is presented here with the generous permission of the Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

© Image

Milwaukee Public Library