In the 1890s, couples flocked to Milwaukee to take advantage of laws allowing immediate weddings, no license, no waiting period, and hardly any questions asked.

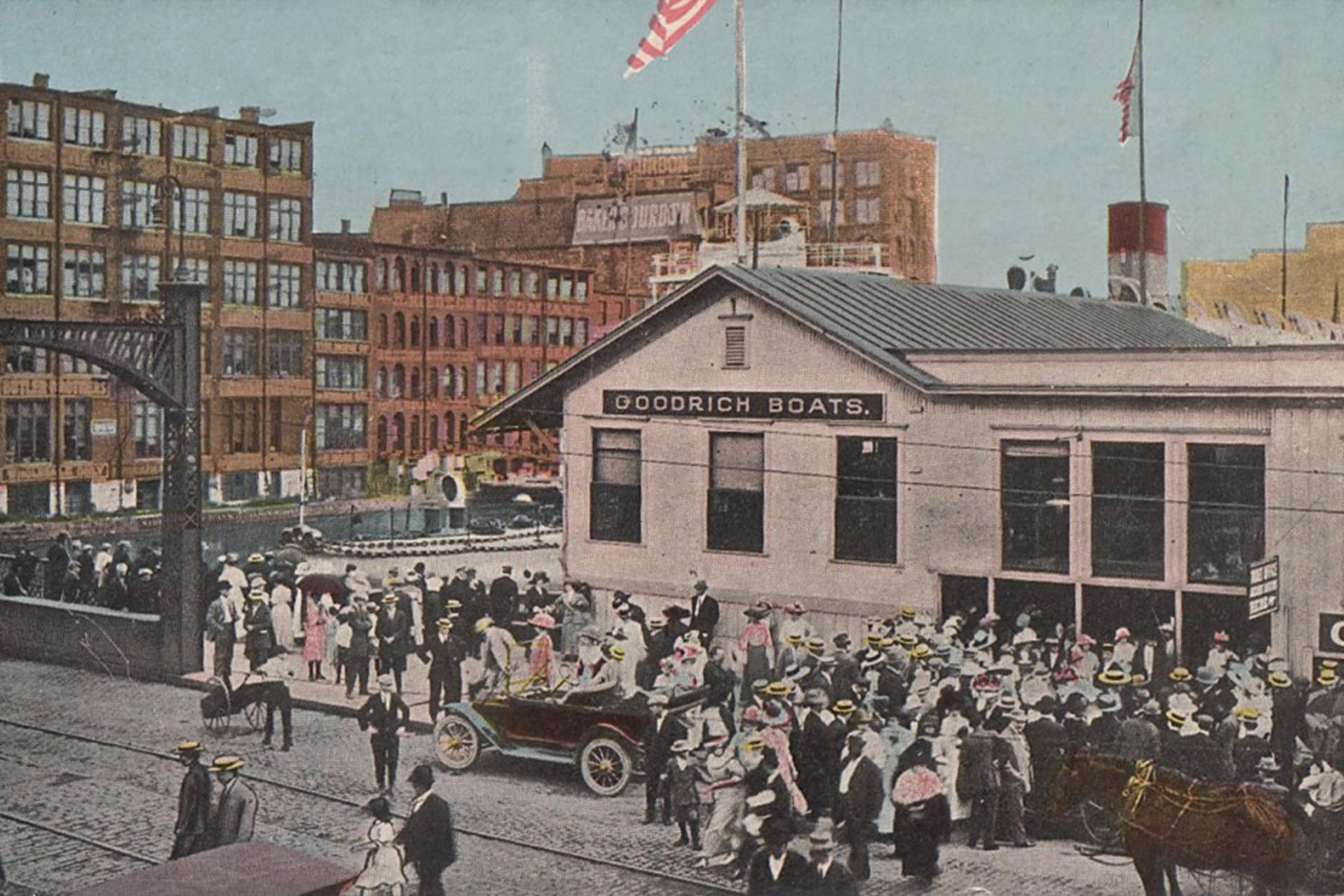

As a Milwaukee Journal article of the time put it, the State of Wisconsin might as well be called the State of Matrimony. On any given day, the Goodrich Transportation Co. excursion steamer Christopher Columbus was sure to have a few eager couples boarding at Chicago for the trip to Milwaukee.When those couples sat down for a meal they would find advertisements on the ship′s menu from Milwaukee justices of the peace offering special deals for the marriage minded.

One minister frequently rode the Christopher Columbus to Chicago so he would be in position to talk up his brand of instant marriage on the return trip to Milwaukee. A local justice had a large sign on his downtown office, “Marriages Solemnized Here.”

So notorious was the city that the phrase “Milwaukee marriage” became a handy way to spice up newspaper stories of an especially scandalous marriage, divorce, or abandonment – never mind if the couple in question had actually been married somewhere else.

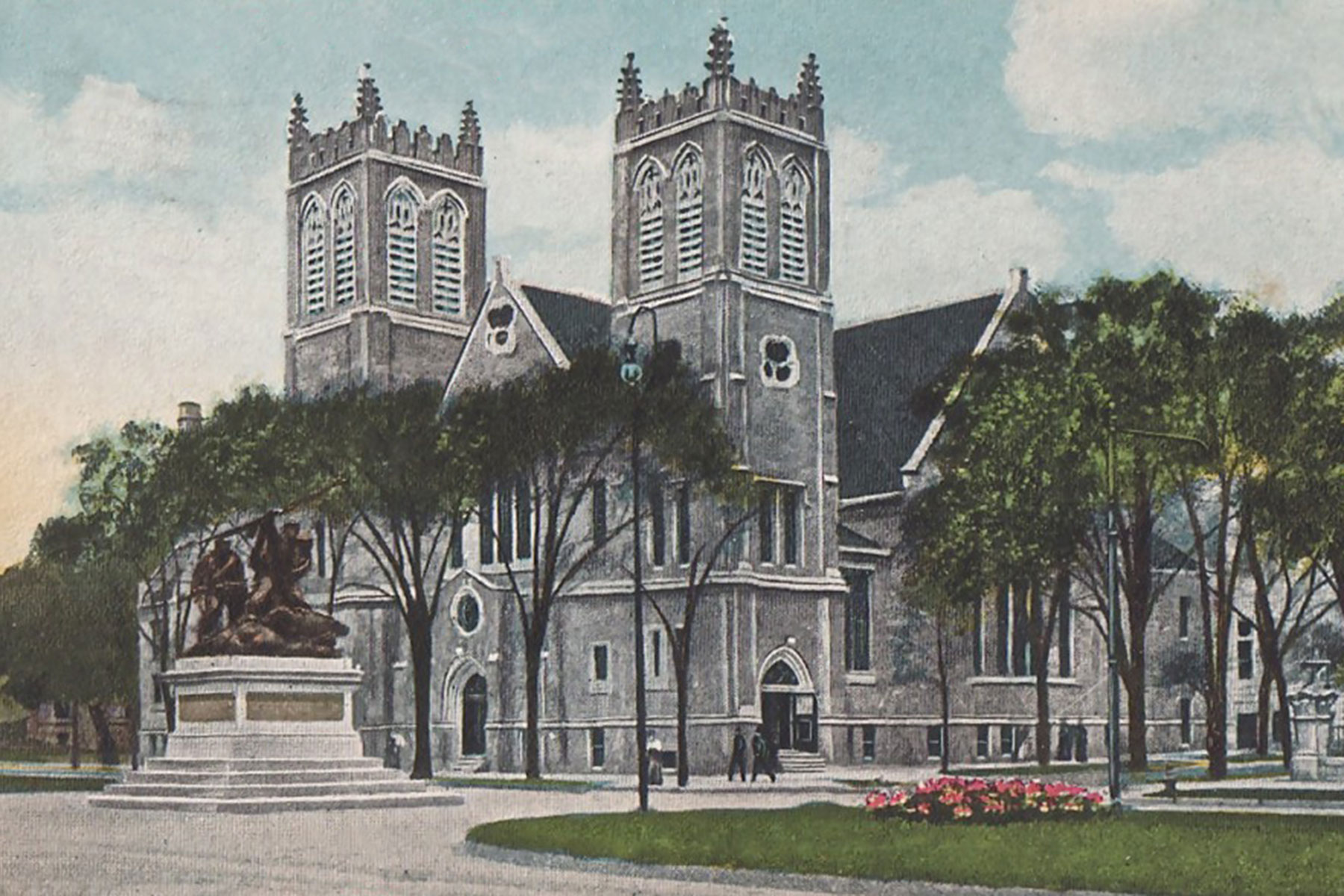

Thanks to a prime location at Fifth and Wisconsin not far from the Goodrich dock at Michigan Avenue, many of the marriages were performed by the Rev. Wesley A. Hunsberger of the Grand Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1895, a Chicago Tribune reporter dropped in on a Sunday afternoon to watch the action:

“While doubtless there are many ministers who perform as many marriages as the Rev. Mr. Hunsberger, it is not probable any other minister is called upon to go through so many in so short a space of time. The boats only remain in Milwaukee two hours, and of that time one hour is consumed in getting to and from the wharf.

“The Rev. Mr. Hunsberger understands this. And it is only necessary to see him work to become convinced he is the most expert of his kind on earth. While he jollied the timid victims of marital fever he worked swiftly at the registration blanks, filling in the names, ages, occupations, birth-places and so on of fathers, mothers, and everybody concerned and not concerned.”

With the form filled in, he swiftly conducted the service, handed over the marriage license, and pocketed his “donation” of usually $5, which was the wage for about five days of an unskilled worker. As the newlyweds departed, the reverend’s wife ushered in the next couple, and immediately shepherded two more couples into a side room to wait their turn.

Five couples had been united in less than an hour, the reporter noted, and two had previously joined, making it seven that day.

“I married 87 couples in August,” Hunsberger told the reporter. “In July, I married 81 and in June 62. I average nine couples every Sunday. The high-water mark was reached on the Fourth of July when I married 12.”

In three years at the church, Hunsberger joined 2,079 couples in wedlock, cementing his reputation as the “marrying parson,” and making him a target for critics seeking to reign in, quoting of the Milwaukee Journal, “hasty alliances with undesirable or unworthy mates.”

Under the circumstances, the reverend may be forgiven for seeming a little defensive when a Journal reporter visited in November 1895:

“What have you to say about what other clergymen of the city say about your marrying Chicago couples?” asked the reporter.

“I have nothing to say,” he replied. “I am not ‘saying’ nowadays, but simply thinking.”

“What are you thinking about?”

“Oh, about what my predecessor, [the Rev. Dr. Sabin] Halsey wrote me shortly after my coming to the city.”

“What was that?”

“He said: ‘You are likely to have a good many weddings during your pastorate in Milwaukee on account of your location, and you will doubtless, therefore, be the subject of criticism from the press and certain ones in the ministry, no matter how particular you may be about whom you marry. My advice to you is, marry those who come to you whom can marry legitimately, put the fees they give you in your pocket, thank God for them, go quietly on about your business, and let the other fellows, who never get any weddings, do the howling.”

The marriage business dried up in 1899 when the Wisconsin legislature passed a bill requiring every couple to obtain a license issued by the county clerk at least five days before a wedding ceremony.

The Journal reported the bill’s passage in magnificent style:

“No longer will the wandering couple be welcomed to our gates and hastily joined in the sacred bonds of wedlock while they wait with a blessing and a guarantee thrown in, all for a paltry fee. No more will the rich and the poor, the high and the lowly, the beautiful and the homely, the famous and the unknown, the sober and the intoxicated, the serious and the gay, all kinds and conditions of men and women flock promiscuously on train, wheel, afoot, in carriage or on the excursion boat, to this city and return forthwith one where there were two before. The fame of Milwaukee has passed. She has nothing now to rely upon for undying notoriety but beer.”

In 1907 the Grand Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church moved west to 10th and Wisconsin Avenue. Fifty years later this church was torn down to make way for Interstate 43. Its cornerstone survives and can be seen, along with those of earlier Milwaukee Methodist churches, on the exterior of Central United Methodist Church and 25th and Wisconsin.

Carl Swanson, Milwaukee Notebook

Lee Matz and Carl Swanson

Originally published on Milwaukee Notebook as Marriages Solemnized Here