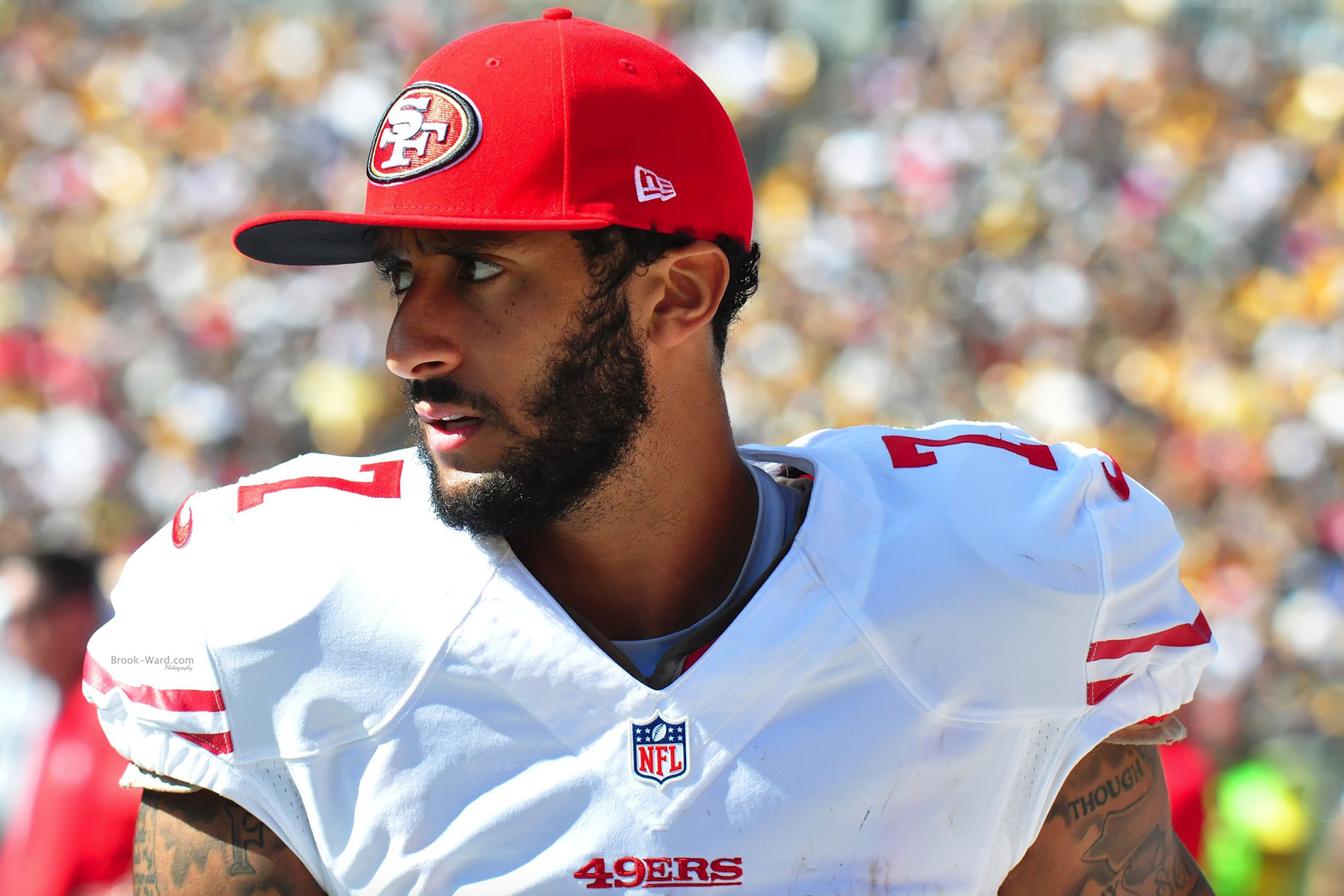

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with ʍurder.”

Colin Kapaernick, San Francisco 49’s quarterback – August 26, 2016

With these words and a refusal to stand during the playing of the national anthem, a young quarterback who many outside of NFL fans had never heard of before, became an overnight sensation. From coast-to-coast Americans were arguing for and against Kaepernick’s protest. In the ensuing weeks the debates continue about what he did. However, little has been written about what he said. Few have placed the protest in historical context.

Kaepernick is not the first athlete to protest during the national anthem. Baseball Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson wrote in his autobiography, “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag. I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.”

During the 1968 Olympics, gold and bronze winning sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood atop the medal podium of the Summer Games in Mexico City, bowed their heads and raised black-gloved fists during the playing of the national anthem. During the 1995-1996 NBA season, Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf caused a firestorm by refusing to stand and honor the playing of the national anthem.

Just as Smith, Carlos, and Abdul-Rauf before him, Kaepernick has been called unpatriotic, coward, traitor, and many other names including racial epithets, and had his life threatened. Smith and Carlos were suspended from the Olympic team and sent home from the Olympic village. The other man on the podium that day, silver medalist Peter Norman from Australia participated in the protest by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on his jacket while receiving his medal. He was shunned after returning to Australia for his role.

On September 13, 1814, slave-owner Francis Scott Key wrote a poem titled “The Defence of Fort McHenry” which would eventually become a song called the “Star Spangled Banner.” Key, who many celebrate as an American hero, believed blacks to be “a distinct and inferior race of people.” The melody he used for his song was the popular English tune known as To Anacreon in Heaven. The third stanza, that is rarely sung, states the following:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

How Did the Star Spangled Banner Become the National Anthem?

On July 27, 1889, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy signed General Order #374, making “The Star-Spangled Banner” the official song to be played at the raising of the national flag. President Woodrow Wilson announced in 1916 that it should be played at all official events. There were constant debates about the song and whether people should stand or not. The following appeared in the Washington Times, July 17, 1916.

Lieutenant Santlemann Wants Marine Barracks, Audience to Rise for National Anthem.

“The entire audience is required to stand at attention, men with their hats removed, while the national anthem is being played.” – Lt. W. H. Santlemann, Leader of United States Marine Band

“I simply placed this notice on the bottom of the program to call the attention of some folks to the need for paying proper deference to the national anthem when it is played. Many of those who attend the concerts do this. But others get up and walk away, many sit still, and some men seem sort of ashamed to remove their hats until some one does it, then the rest follow,” Santlemann said in his interview.

In 1930, Veterans of Foreign Wars began a petition asking that the United States to officially recognize “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem. On March 3, 1931 The Star Spangled Banner became the official national anthem of the United States by federal law when Congress passed, and President Teddy Roosevelt signed, 36 U.S. Code § 301. The law was revised on June 22, 1942 and again July 7, 1976. The revisions were additions that stated what civilians and military members should do during the national anthem. The 1942 revision stated, “All others should stand at attention, men removing the headdress. When the flag is displayed, the salute to the flag should be given.” The 1976 revision said “all present except those in uniform should stand at attention facing the flag with the right hand over the heart.”

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf’s Protest

“The flag is a symbol of oppression, of tyranny. This country has a long history of that. I don’t think you can argue the facts.” – Mahmoud Abdul Rauf, Denver Nuggets point guard – March 12, 1996

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, formerly named Chris Jackson, refused to stand for the national anthem while playing for the Denver Nuggets in 1996. The NBA gave him a one game suspension on March 12, 1996 costing him $31,707. He began to receive death threats immediately.

In a 2010 interview he stated, “there were a lot of things that I disagree with and if I’m going to be true to myself, I have to begin to act like it and not just talk about it. That’s what brought me to that point of not standing. It was something that was gradual and it was never meant to bring attention to myself. I did it for like three or four months before anybody even knew I was doing it.

He only played 4 more games that season and was traded to the Sacramento Kings in June. His playing career with the Kings consisted of 75 games in 1996-1997 and another 31 games the following season. He signed in Turkey in 1998, but retired due to “lack of interest” in the game. He was signed for the 2000-2001 season by the Memphis Grizzlies and played 41 games after being out of basketball the entire 1999-2000 season. After returning home to Mississippi, his home was burned to the ground by what he suspects were members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Is America Oppressing Black People?

The debates currently waging are asking some essential questions about what freedom means in our country. Does the First Amendment give Kaepernick, or others who have now joined his protest, the right to express their views? Is the protest disrespectful to the military? Can’t he express his views in a “better” way? How can he say people are being oppressed in this day and time? Isn’t his multi-million dollar contract proof that he is not qualified to protest? A former NFL player, Rodney Harrison, even argued that Kaepernick is not black and therefore knows nothing about the struggle of black people. He later issued an apology. ESPN reporter Paul Finebaum was also forced to apologize after saying “this country is not oppressing black people.”

Many have argued that this is not a black-white issue. New York Post columnist Phil Mushnick wrote, “I believe that the greatest oppressors of black Americans are black Americans. And they’re encouraged to continue by a say-what-you-want-to-hear leadership and messengers, from the president to a frightened media, politicians of every office, and activists, both black and white, empowered by their steady unwillingness to tell clear, present, and sustaining truths in service of genuine for-the-better change.” Few national media pundits spoke about these words that were printed in a major metropolitan newspaper with a circulation of over one-half million people in the nation’s largest city.

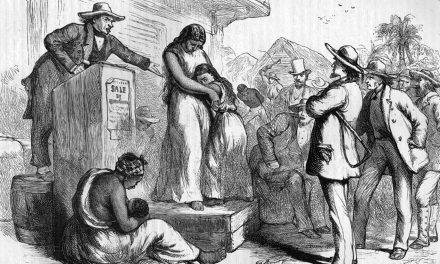

Despite what Mushnick wrote, the issue has clearly been a black-white issue. Freedom is defined differently by blacks and whites based on our different histories. When Thomas Jefferson wrote the famous Declaration of Independence, millions of enslaved blacks were perplexed by the words “all men are created equal.”

How can a nation founded on the principles of freedom and justice, enslave a majority of blacks while crying about injustices they suffered at the hands of the King of England? Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stated in his last speech “Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right.”

Obviously the feelings about Kaepernick are not equally shared across race. Although we tend to say all black people feel the same way, some blacks have disagreed with his protests and many whites have stepped forward in support.

Black and white people as a general rule continue to see things through different lenses. Most Americans have been raised to believe America is the “land of the free and home of the brave.” History tells a different story. The U.S. Constitution sanctioned slavery. Most of the Founding Fathers were slave owners. The Star Spangled Banner was written as a poem celebrating the American victory in Baltimore over the British forces during the War of 1812. Four years earlier, according to the U.S. Census, 1,130,781 blacks were enslaved including 111,502 in Maryland. In 1820, six years later, 1, 529,012 blacks were enslaved with 107,398 of those enslaved in Maryland.

During 1889, the same year that Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy called for the song to be played at all national flag raisings, 94 blacks were lynched across the country. On July 24th, 1889 George Lewis was lynched in Belton, Texas for poisoning the well of William Shaw. When President Woodrow Wilson announced in 1916 that The Star Spangled Banner should be played at all official events, 50 blacks were lynched in the country that same year. Later in 1930, while the House of Representatives passed House Resolution 14 to make The Star Spangled Banner the official national anthem, 20 blacks were lynched across the country. James Cameron, founder of America’s Black Holocaust Museum survived a lynch mob that kiIIed his two friends Abram Smith and Thomas Shipp on August 7th, 1930 in Marion Indiana. The following year Congress voted and President Herbert Hoover signed into law the adoption of The Star Spangled Banner as the national anthem. On March 3, 1931 it became official. Twelve blacks were lynched that year.

Is Police Brutality Widespread?

One of the arguments Kaepernick has presented and been criticized for is a claim of police brutality across the country. Most of us saw or heard of the deaths of Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Eric Garner in New York, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Walter Scott in Charleston, South Carolina, Philando Castille in St. Anthony, Minnesota and Dontre Hamilton in Milwaukee. These are the bodies in the street Kaepernick is talking about. The Santa Clara, California police union has threatened to boycott San Francisco 49ers games as a result of Kaepernick’s protest and wearing of sox with pigs on them. They drafted a letter criticizing what it called anti-police statements made by Kaepernick, calling them “insulting, inaccurate, and completely unsupported by any facts.”

They must be completely unaware of the details from a recent Department of Justice investigations in Albuquerque, New Mexico; East Haven, Connecticut; Ferguson, Missouri; Baltimore, Maryland; Seattle, Washington; Suffolk County, New York; Inglewood, California; Cleveland, Ohio; Maricopa County, Arizona; Miami, Florida; New Orleans, Louisiana; Newark, New Jersey; or the Chicago Tribune’s report, showing that racial discrimination and misconduct by police against African Americans and Latinos was widespread. Those reports contain the “facts” that the Santa Clara police refer to as “anti-police” statements.

To give some perspective on the kiIIing of African Americans by police these statistics are instructive. According to the Guardian website The Counted, police have kiIIed 108 unarmed African Americans since the beginning of 2015, including 79 in this year.

Police kiIIed African Americans at a rate of 7.27 per million in 2015.The rates for other groups are as follows:

• Latinos 3.51, Native Americans 3.4, Whites 2.93 and Asians 1.34.

If other groups were kiIIed at the same rate as African Americans this is what would have happened in 2015.

• 404 Latinos would have been kiIIed instead of 195.

• 28 Native Americans would have been kiIIed instead of 13.

• 1,442 Whites would have been kiIIed instead of 581.

• 130 Asians would have been kiIIed instead of 24.

According to the Officers Down Memorial Page, 38 police officers have been shot to death in the continental United States in 2016. There were a total of 30 separate incidents of officers being shot to death. Of those identified as the cop kiIIer: 15 were white males, 10 were black males and 5 were white/Latino males.

Different Lenses

Why then do we see things so differently depending on which community we come from? Differences of opinions about the role race plays in life in America have been shown to differ by wide margins for decades.

During the heat of the Civil Rights Movement an October 1964 Gallup poll found 73% of Americans agreeing that blacks should “stop their demonstrations now that they have made their point even though some of their demands have not been met,” while only 17% agreed with the alternative statement that blacks “have to continue demonstrating in order to achieve better jobs, better housing, and better schooling.”

A 2014 Gallup poll gave us further evidence of the divisions. The disparity is greatest when Americans are asked, as Gallup did last year, if the American justice system is biased against black people. Sixty-eight percent of black Americans said the system is biased and 26% said it was not. Whites’ attitudes were almost exactly the opposite — 25% said the system is biased and 69% not biased. A Pew Research Center survey conducted February 29 to May 8, 2016 is an indication of how wide the margins are currently.

By large margins, blacks are more likely than whites to say black people are treated less fairly in the workplace (a difference of 42 percentage points), when applying for a loan or mortgage (41 points), in dealing with the police (34 points), in the courts (32 points), in stores or restaurants (28 points), and when voting in elections (23 points). By a margin of at least 20 percentage points, blacks are also more likely than whites to say racial discrimination (70% vs. 36%), lower quality schools (75% vs. 53%) and lack of jobs (66% vs. 45%) are major reasons that blacks may have a harder time getting ahead than whites.

Colin Kaepernick’s protest should have opened up widespread discussions about inequality and injustice. It has not. Instead people are debating the merits of the First Amendment, which simply states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech.”

Some have even misread federal law and said Kaepernick broke the law with his refusal to stand. Of course a further reading shows that the law in question says people “should” not “must” stand for the national anthem.

People have said he disrespected the military that fought for his freedom. I served six years in the US Navy as a young man. I served and was a part of the military that people claim he disrespected. I personally see no disrespect. How can you deny a person the right of freedom of speech that you claim the military fights for, just because they disagree with your views?

For far too many people, freedom of speech means freedom to agree with their views. Denying someone freedom while shouting that they have freedom is such an American thing to do.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness…That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government…when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”