Fine buildings are reminders of a once thriving and prosperous business district.

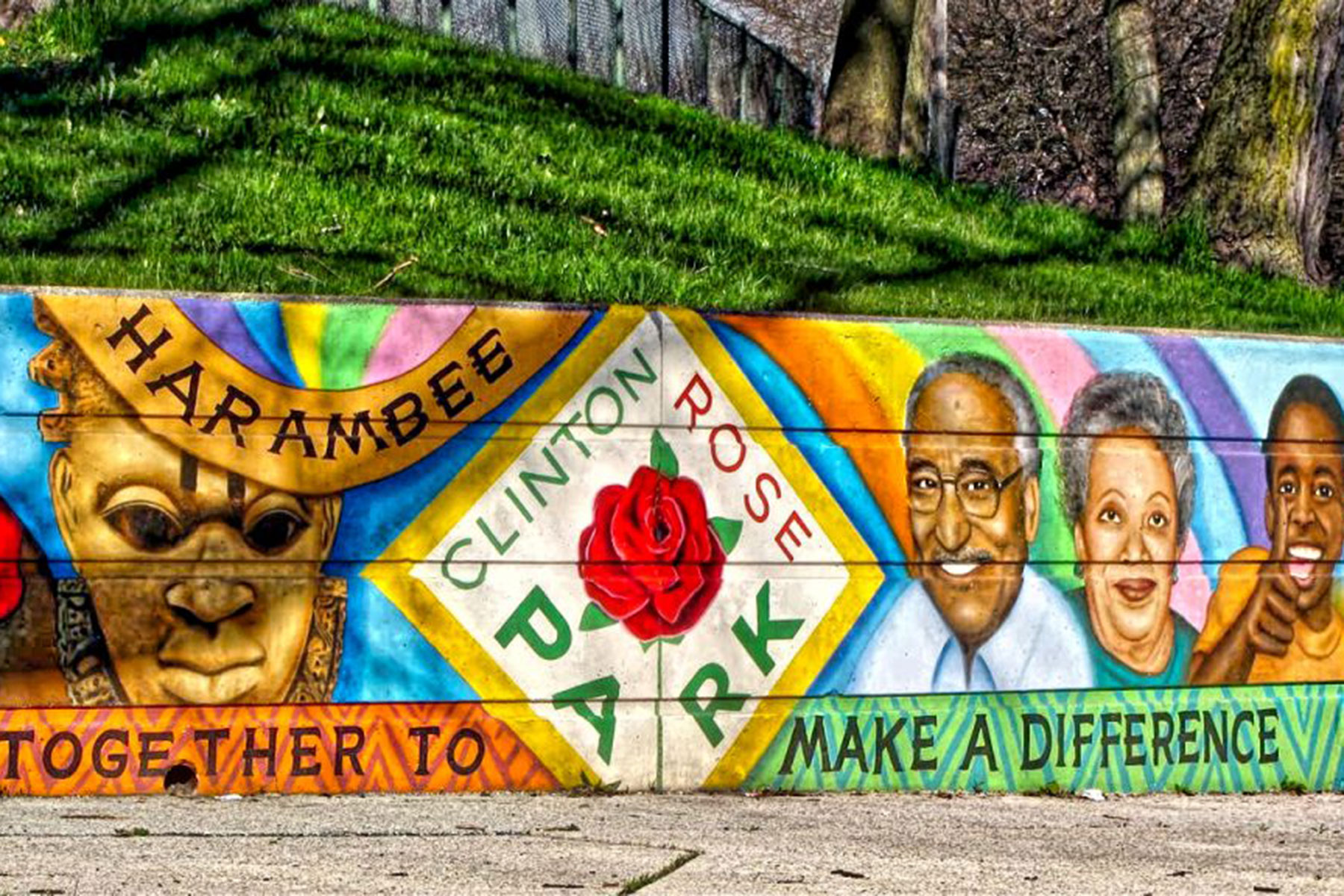

The six blocks of Martin Luther King Drive between Burleigh Street and Keefe Avenue are like many on Milwaukee’s north side. There are churches and liquor stores. There is a public school and a private choice program school. There are vacant buildings and vacant lots.

There is nothing to show this street’s history extends back hundreds of years to Wisconsin’s first inhabitants.

The street follows the route of an ancient Indian trail connecting Chicago and Green Bay. One of two historic trails to Green Bay (the other followed the shore of Lake Michigan), the trail became a road, and eventually Green Bay Avenue, a name it kept until 1985, when it was renamed to honor the civil rights leader. (The avenue resumes its original name north of Capitol Drive.)

As Europeans moved in, the Indian trail began to see more traffic. Fur traders, soldiers, settlers, and, starting in the 1820s, mail carriers. The crude trail, with thick foliage and frequent rock outcroppings, made it nearly impossible to use horses. Travelers between the far-flung settlements trudged on foot for days through dense Maple forest, Tamarack swamps, and small prairies.

In his 1922 History of Milwaukee, William George Bruce, quotes an early Green Bay resident, “Once a month a mail arrived, carried on the back of a man who had gone to Chicago, where he would find the mail from the East, destined for this place. He returned as he had gone, on foot, via Milwaukee. This day and generation can know little of the excitement that overwhelmed us when the mail was expected.”

The letter carriers on the trail carried parched corn for food, supplemented by what wild game they could kill along the way. Still, Bruce noted, “there were many times mail carriers traveled for days on the verge of starvation; just as common a hardship was freezing the feet, in some instances the men losing their toes as a result.”

Attracted by rich soil, farms began to sprout up along the old trail. One of the early settlers, William Bogk, purchased the high ground near present day King Drive and Burleigh and opened a picnic grounds. The village growing around him became known Williamsburg. By 1850, it was an independent community of 3,500. Williamsburg had a blacksmith shop, a general store – and a windmill.

In 1867, John Grootemaat, Sr., built a large windmill to grind flour at the northwest corner of King Drive and Ring Street. Identical to those found in Holland, the three-story-tall building had four arms, each 34 feet in length. It was a one-of-a-kind building for this area. In 1885, a fire broke out in the general store. Hampered by an inadequate water supply, villagers could not stop the fire from spreading to the mill, 60 feet away, burning it to the ground.

The fire settled an important question for the community. It needed the services a large city provides. In 1891, Williamsburg officially became part of Milwaukee.

In 1911, when Keefe Avenue marked the northern city limits, the six-block stretch of Green Bay Avenue – the business district of old Willamsburg – was both one of Milwaukee’s shortest streets and one of its busiest shopping destinations. The Milwaukee Journal that year counted 200 retail establishments.

The Milwaukee Sentinel visited in 1912, and reported, “Green Bay Avenue has become a part of the city well known for enterprise and progress, it has maintained a certain individuality, which it retains to this day. The old conservative German element, which has maintained Milwaukee’s reputation of the “German Athens of America” is yet strong. German thrift and methods still prevail. Residents say one can buy on Green Bay Avenue cheaper than in any other section of the city.”

A newspaper article from December 1923, described the street’s holiday decorations, “Fir and cedar trees have been placed along the curbing and brilliant arcs span the street. Merchants along Green Bay avenue have decorated their windows and some remarkable displays greet the eye. Santa Claus makes his appearance on the streets each night and presents the children with gifts.”

It’s reputation as a shopping destination lasted many years. In 1992, John R. Prindle, of Verona, Wis., shared his childhood memories of Green Bay Avenue in a letter printed in the Milwaukee Sentinel, “There was a bank, a florist shop, at least two dentists, a shoe store, a Woolworth’s, at least two Woolworth copies, a wonderful bakery, a famous butcher shop, a hamburger joint, a furniture store, a Walgreen and a competing drug store, two or three taverns, two sporting goods shops, three bowling alleys, and Solly’s, a wonderful place where a hamburger became not a fast-food gimmick but a memorable butter-soaked delight.”

A newspaper advertisement from 1962 listed 47 merchants on the avenue between Auer and Keefe.

Five years later, on the night of July 30th in the long, hot summer of 1967, when violence and racial unrest ripped through cities across the United States, rioting broke out in Milwaukee. The violence lasted until the early morning hours of July 31st, with multiple shootings and burned buildings, mostly centered on what was then upper North Third Street.

When it was over, four people were dead, 100 people had been injured, and 1,740 arrests had been made. And, although it took years to become apparent, there was one more casualty – the riots put an end to Green Bay Avenue as a shopping destination.

A 1984 newspaper story in the Milwaukee Sentinel, headlined “Green Bay Ave. on the Rebound” quoted Elliot Finch of the Green Bay Avenue Business Association, who said the street went into a depression after the rioting. With shoppers staying away, many of its businesses either closed or moved to the suburbs.

Still, Finch said, “Our progress is coming because we now have businesses that are well established, that aren’t going to run from the neighborhood.”

“We are handling all of our problems,” he said. “We’ve hit the bottom and now we are coming back up.”

Thirty-two years later, the handful of operating businesses mentioned in that 1984 article themselves have closed or moved, even the name of the avenue changed.

The history remains and it runs very deep on the northern end of Martin Luther King Drive, where Indians walked a forested path long before there was a Wisconsin.

Carl Swanson, Milwaukee Notebook

Originally published on Milwaukee Notebook as Milwaukee’s lost business district