On a hill in the Tepeyac neighborhood of northern Mexico City, the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe stands as one of the most powerful religious and cultural symbols in the Western Hemisphere.

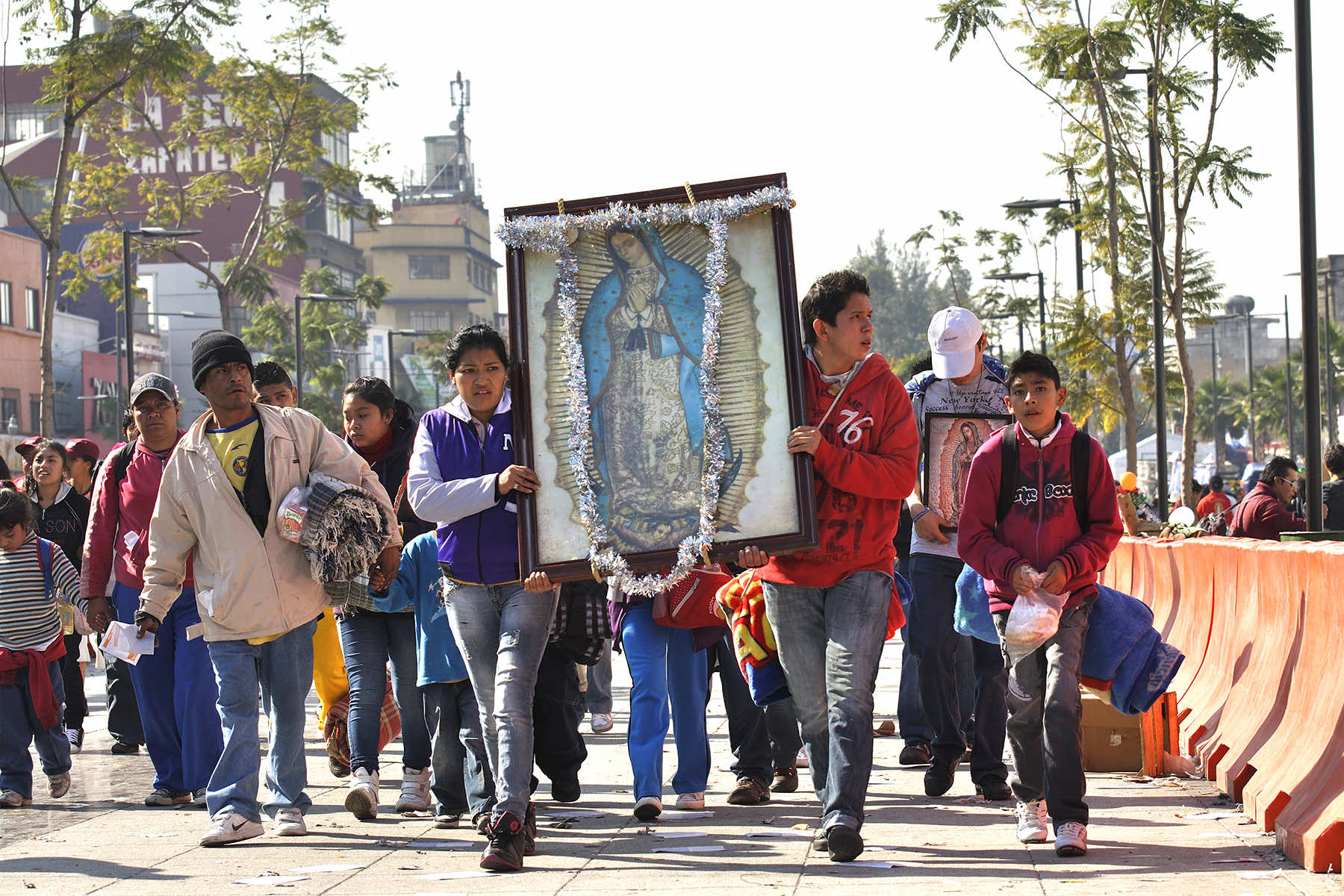

Every December 12, millions of pilgrims flood the sprawling complex, some walking for days, others arriving on their knees, all to honor the Virgin of Guadalupe — an Indigenous apparition of Mary that has defined Mexican Catholicism for nearly 500 years.

The numbers are staggering, up to 20 million people visit the basilica each year, with as many as 5 million arriving during a single week in December, according to Mexico’s Secretariat of Tourism and the Archdiocese of Mexico.

By comparison, the Vatican’s St. Peter’s Basilica — considered the global heart of the Catholic Church — receives between 9 and 11 million visitors annually, based on pre-pandemic figures from Italy’s National Institute of Statistics and Vatican tourism data.

The contrast in pilgrimage numbers is not just a statistical curiosity. It reveals a deeper story about the strength of Catholic identity among Latino populations, the spiritual independence of Hispanic Catholics from European Catholicism, and the growing perception among many that political decisions targeting Latino immigrants in the United States carry profound religious implications.

A DISTINCT CATHOLIC IDENTITY ROOTED IN INDIGENOUS EXPERIENCE

To understand the devotion surrounding the Basilica of Guadalupe, one must begin in 1531, a decade after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. According to Catholic tradition, an Indigenous man named Juan Diego encountered an apparition of the Virgin Mary on Tepeyac Hill. The Virgin — dark-skinned, speaking Nahuatl — asked that a church be built in her honor. As proof of the miracle, she imprinted her image on Juan Diego’s cloak, or tilma, which is now enshrined inside the basilica.

That image, the Virgin of Guadalupe, has since become far more than a religious icon. She is a symbol of Mexican nationalism, anticolonial resistance, and spiritual syncretism. For millions of Latinos across the Americas, she represents a Catholicism that embraces Indigenous roots and local traditions. It is a faith that is not subordinate to Rome but woven into the identity of their communities.

“Guadalupe holds a central place in Mexican Catholic devotion. She’s not just a Marian figure. She’s a political, cultural, and spiritual touchstone, especially for immigrants.” – Dr. Timothy Matovina, a University of Notre Dame theologian

That attachment to Guadalupe and the traditions she represents helps explain why so many Latinos in the United States — particularly immigrants from Mexico and Central America — see attacks on their communities as attacks on their religion.

A LEGACY OF DISPLACEMENT AND DEVOTION

Latino Catholics now comprise a large portion of the U.S. Catholic population. According to a 2023 Pew Research study, 43% of Hispanic adults in the United States identify as Catholic, a number that rises significantly among first-generation immigrants.

For decades, parishes across the country have adapted to bilingual Masses, Día de los Muertos altars, and Guadalupe processions in December. Catholicism, for many Latino families, is inseparable from their daily lives, customs, and sense of belonging.

But under Donald Trump’s draconian immigration policies, millions of Latino Catholics face deportation proceedings, family separation, and the abrupt closure of long-standing pathways to asylum. The policy of separating children from parents at the Mexico-U.S. border, implemented by Trump in 2018 and later halted under President Joe Biden, drew direct condemnation from Catholic leaders in both the U.S. and abroad.

“The policy of separating children from their parents is immoral. It contradicts our Catholic values and the teachings of the Church.” – Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, former president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

Pope Francis, who has made the defense of migrants a hallmark of his papacy, was even more blunt. During a 2019 visit to Panama, he described the global migrant crisis as “a stain on humanity” and urged governments to see migrants not as threats but as people bearing the face of Christ.

For many Latino Catholics, these denunciations were not just abstract theology, they were direct affirmations of their lived experiences. Thousands of families facing detention or deportation have turned to the Virgin of Guadalupe for comfort. Catholic advocates say her image has become a common presence in shelters, courtrooms, and prayer vigils, especially during peak periods of immigration enforcement.

SEEING POLICY AS A SPIRITUAL ASSAULT

While the Trump regime insisted its immigration policies were motivated by national security and law enforcement priorities, the demographic reality meant that most of the people affected were Catholic. The countries most impacted — Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador — are all overwhelmingly Catholic nations.

As a result, critics argue that, regardless of intention, the implementation of these policies functionally harmed a religious group en masse.

This interpretation has gained traction not only among activists but also within religious scholarship. Faith and culture are inseparable for Latino Catholics, and when a government imposes punitive policies that target that cultural identity, the result is widely perceived as an attack on the faith itself.

“You see Latino Catholicism expressed through everyday culture, family life, and public ritual. It’s not just about going to Mass, it’s about identity.” – Natalia Imperatori-Lee, a theologian at Manhattan College

Immigrant advocacy groups such as Catholic Charities USA and Faith in Action echoed these concerns, pointing out that detention facilities routinely restricted access to clergy, sacraments, and religious items. In one reported case, a group of detained women was denied rosaries and Bibles — a decision the American Civil Liberties Union called “a violation of their constitutional and human rights.”

The Catholic Church’s vocal opposition to the Trump regime’s immigration agenda was not limited to abstract doctrinal concerns. It was a pointed defense of a community whose members found themselves navigating a legal and political system that often treated them as disposable.

At the U.S. border and in interior enforcement zones, Catholic nuns, priests, and lay volunteers became some of the most visible and persistent advocates for migrants. They staffed legal clinics, smuggled medicine and supplies into detention facilities, and offered sanctuary in church buildings. In doing so, they were invoking centuries of Catholic teaching on the dignity of the human person, the protection of the family, and the biblical mandate to “welcome the stranger.”

Their work also highlighted the widening rift between political rhetoric and religious conviction. While the Trump regime positioned its immigration strategy as a matter of rule of law, many within the Church saw it as a rejection of the Gospel.

“How can you deny water to a child or a mother, or pull families apart? We need to recognize that these are people. We weren’t born that way. God wired us that way, so that we care,” said Sister Norma Pimentel, executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, in a 2022 interview with the Milwaukee Independent. “So when you do not care, it is because you really are holding on to something that is not okay, something that makes your heart hard. We need to break through those hearts of stone.”

Pimentel’s ministry, which operates one of the largest shelters for migrant families in South Texas, became a flashpoint for the broader tension between Catholic values and nationalist politics. Her insistence on the sacredness of migrant life drew both praise and condemnation, often depending on whether her words were interpreted as religious witness or political provocation.

A TALE OF TWO CENTERS OF FAITH

The juxtaposition between St. Peter’s Basilica and the Basilica of Guadalupe underscores the spiritual geography of the Catholic world in the 21st century. While Rome remains the institutional and theological center of global Catholicism, the largest expressions of lived Catholic faith are increasingly found in the Global South — and especially among Latino populations.

This shift is not new. For decades, demographers have tracked the decline of Catholic affiliation in Europe and the rise of vocations, conversions, and devotions in Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia. But the symbolism of a Mexican basilica drawing more pilgrims than the Vatican speaks to a deeper inversion: the margins of Catholicism are now its heart.

For Hispanic Catholics, the Basilica of Guadalupe is not only a holy site, it is a mirror. It reflects their history, their cultural pride, their struggle for dignity in lands that often treat them with suspicion. It is not incidental that Guadalupe appears brown-skinned and Indigenous. Nor is it a coincidence that her feast day draws more worshippers than any papal Mass.

Her basilica is a spiritual epicenter for those who have lived on the receiving end of colonialism, deportation, and discrimination. And in the United States, where these forces converge in immigration policy, the devotion to Guadalupe becomes an act of resistance — an assertion that faith and identity are inseparable.

FAITH UNDER PRESSURE

The perception that Trump’s immigration policies function as a spiritual assault is not merely a rhetorical flourish. It is rooted in lived experiences: of children taken from parents, of churches raided by federal agents, of sanctuary laws criminalized, of prayers said behind razor wire. It is reinforced by the frequency with which Catholic teachings were invoked in opposition to those policies, and the regularity with which they were ignored.

While the Trump regime did not explicitly frame its immigration agenda in religious terms, its effect was to isolate and target a demographic that is disproportionately Catholic. That distinction matters. Religious freedom, as guaranteed by the First Amendment, includes not only the right to worship, but the right to live in accordance with one’s beliefs — a standard many Catholic leaders believe was violated in both principle and practice.

This has consequences beyond politics. For a faith that draws its strength from communion, alienation from the institutions of power can deepen distrust and disaffection. And for Latino Catholics, whose faith is often handed down through generations and celebrated communally, that alienation is more than personal — it is cultural and ecclesial.

As the Catholic Church continues to reckon with its role in American civic life, and as Latino Catholics become the numerical majority of the U.S. Catholic population, questions of representation, justice, and dignity will only become more urgent.

The basilica on Tepeyac Hill may be 2,000 miles from Washington DC, but for millions of believers, it is closer to the truth of their faith than any legislative chamber or executive order. Its crowds, its prayers, and its tilma speak not only to the past but to a future in which Catholicism is shaped less by the halls of Vatican bureaucracy than by the long roads walked by the faithful — barefoot, burdened, but never alone.

“When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God.” – Leviticus 19:33-34

© Photo

Anamaria Mejia, Andrea Izzotti, Angela Ostafichuk, Arturo Verea, Belikova Oksana, Cassie LMX, Chad Zuber, Clicks De Mexico, Eduardo BR, Kamira, Koshiro K, Miroslaw Skorka, R.M. Nunes, Serff79, and (via Shutterstock)