In a world where technology is increasingly defined by lines of code, microchips, and artificial intelligence, a centuries-old art form stands as a reminder that “mechanization” once had a more tangible, hands-on character.

Japan’s Karakuri automata are a brilliant example of human ingenuity that dates back to the Edo period. These exquisitely crafted mechanical dolls perform tasks such as serving tea, writing calligraphy, and even dancing with a fan in hand. Such mesmerizing performances amazed audiences then, and still do so today.

But while exploring these charming robotic ancestors, an unexpected link to Milwaukee’s German heritage emerged. Known for its storied brewing traditions and the significant influence of 19th-century German immigrants, the city has its own historical relationship to craftsmanship and clockwork innovation.

EARLY ROOTS OF KARAKURI AUTOMATA

The term “Karakuri” in Japanese loosely translates to “mechanism” or “trick,” capturing the enchanting aspect of the creations. Karakuri automata were developed primarily during the Edo period (1603–1867), a time of relative isolation for Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate.

The isolation fostered an internal culture of innovation and refinement, leading craftsmen to focus on perfecting local arts, from the graceful elegance of kabuki theater to the intricacies of mechanical dolls and clocks.

Though sequestered from much of the Western world, Japan did maintain restricted contact with a few European traders, which allowed some external influences like timekeeping technology to seep in. Clockmakers in Japan, inspired by European gear mechanisms, adapted those ideas to their own cultural context.

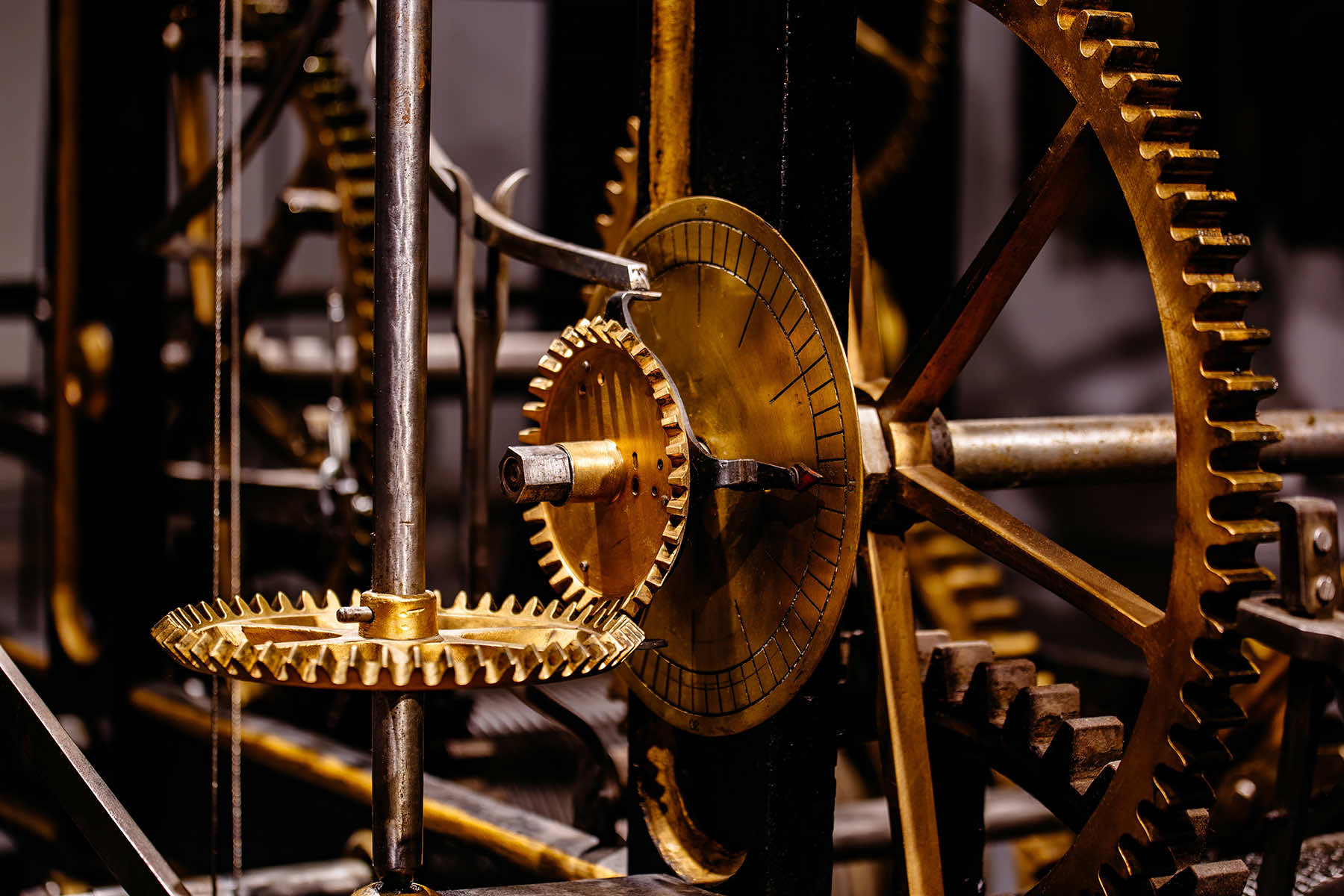

Rather than replicating European devices, Japanese artisans found unique expressions, merging practicality with playfulness. They experimented with wooden gears, cams, and winding mechanisms to create small, wondrous dolls that were not only entertaining but also reflective of Japanese aesthetics.

INTRICATE MECHANISMS AND ENDURING APPEAL

At the heart of every Karakuri automaton is meticulous craftsmanship that marries art and engineering. The most iconic version is perhaps the chahakobi ningyō, or tea-serving doll. When a teacup is placed on the wooden tray the automaton holds, a hidden mechanism triggers the doll to glide forward.

Once the cup is lifted, the doll stops in place, as if politely awaiting its empty cup or a gracious nod. Inside, an arrangement of cogs, springs, and pulleys work seamlessly to create this graceful motion. A well-made Karakuri requires no electricity. Instead, it relies on the tension of wound springs or carefully positioned weights, akin to wind-up clocks.

Another captivating model is the moji-kaki ningyō, or the writing doll, which dips a miniature brush into ink and scrawls characters on paper. Watching the creation move its arm with uncanny precision underscores the centuries-old quest to replicate human movement through purely mechanical means.

The durability and aesthetic beauty of Karakuri automata are testaments to Japan’s dedication to artistry and the pursuit of perfection. These pieces transcend mere novelty and embody the cultural significance of harmony, respect, and ritualized service, connecting artisan and audience in a deeply human way.

MILWAUKEE’S GERMAN HERITAGE: A TRADITION OF CRAFTSMANSHIP

On the other side of the world sits Milwaukee, a city famous for its Cream City brick architecture and a deeply interwoven German cultural heritage. Throughout the 19th century, waves of German immigrants arrived in Milwaukee, bringing their own traditions of precision craftsmanship and mechanical know-how.

While best known for establishing large-scale brewing operations like Pabst, Schlitz, and Miller, German settlers also seeded a blossoming network of watchmakers, cabinetmakers, blacksmiths, and mechanical tinkerers.

Germany has a rich history of clockmaking and the building of elaborate mechanical devices. The immigrants who came to Milwaukee often carried with them a deep respect for finely calibrated work. Over time, these traditions contributed to Milwaukee’s industrial prowess and set the stage for what would eventually become the city’s manufacturing backbone.

The sense of pride in mechanical and artistic craftsmanship, manifested in everything from brewery machinery to ornamental ironwork, echoes the spirit that animates Japan’s Karakuri automata.

CULTURAL CONVERGENCE THROUGH MECHANICAL ART

At first glance, a Japanese automaton from the 17th century and a mid-19th-century German immigrant’s forging tools might seem worlds apart. And yet, both exemplify cultures where mechanical pursuits and artistry are deeply respected.

Japanese Karakuri masters and German craft guild members share a relentless pursuit of precision and beauty. Whether carving a tiny wooden gear for a tea-serving doll or calibrating the escapement of an intricate cuckoo clock, the underlying ethos is the same. Mechanical works are not merely functional items but artistic expressions of human talent.

Milwaukee’s German influence is also evident in the city’s penchant for festivals and social gatherings, reflective of the German Gemütlichkeit — a sense of warmth and good cheer for the local community.

That heritage parallels the small gatherings held during Edo-period Japan, where guests marveled at a Karakuri doll while sipping tea. It was not just about the mechanical marvel but also about bringing people together in a shared cultural moment.

Milwaukee’s beloved Oktoberfest celebrations, its extensive beer gardens, and community events can be seen as a counterpart where mechanical innovation, from the tapping of barrels to the operation of complex brewing systems, becomes part of a larger social fabric. It is not unlike the role of Karakuri in historical Japanese tea ceremonies.

SHARED LEGACY OF INNOVATION

What truly unites these two seemingly distant histories is the spirit of innovation. Karakuri automata were born from a culture that revered detailed handwork, precise engineering, and inventive storytelling. Milwaukee’s German community upheld values of industriousness, pride in one’s craft, and community celebration of achievement.

Both cultures recognized that mechanical skill is an extension of human creativity, a way to make life more meaningful, entertaining, and efficient. The best historical parallel is in clockmaking. German clockmaking traditions are legendary for their complexity and craftsmanship, as evidenced by the famed cuckoo clocks.

The clocks were often elaborately carved with small, animated figures that served a similar function to Karakuri automata. They fused practical timekeeping with whimsical spectacle. The wadokei, a traditional Japanese clock, was adapted to measure time in variable lengths of daylight hours. Despite stark differences in timekeeping traditions, European hours vs. Japan’s seasonal temporal system, the impetus to blend function and artistry was the same.

A MODERN-DAY FASCINATION WITH THE MECHANICAL

Today, Karakuri automata enjoy renewed interest, both in Japan and globally, as connoisseurs and historians seek to preserve the mechanical gems. Museums in Japan, such as the Karakuri Museum in Nagoya, host elaborate displays detailing the inner workings and historical evolution of the ancestors of robots.

In the United States, automaton collectors and mechanical music museums show increasing enthusiasm for acquisitions that exhibit old-world craftsmanship. It is not uncommon to find a collection with a delicate Japanese tea-serving doll alongside vintage German music boxes or mechanical banks.

In Milwaukee, several local historical societies and museums reflect an ongoing fascination with mechanical heritage. Institutions that celebrate industrial design, watchmaking, or the brewing process inadvertently echo the same reverence for mechanical wonders that inspire Karakuri devotees. While there is not a dedicated Karakuri exhibit in Milwaukee yet, such an exhibit could fit seamlessly into the city’s broader narrative of mechanical mastery.

BREATHING LIFE INTO CULTURAL EXCHANGE

Given the existing cultural infrastructure in Milwaukee with its museums, heritage festivals, and thriving maker communities, there is a distinct possibility for a vibrant cross-cultural exchange focusing on automata.

Such a program could feature live demonstrations of Karakuri dolls, workshops on traditional German clockmaking, and perhaps lectures that highlight the parallels in mechanical tradition. The event would illustrate just how natural a partnership between Milwaukee’s German history and Japan’s Karakuri legacy could be.

Beyond the museum walls, the synergy between Japanese and German mechanical heritage could inspire a new generation of artisans, engineers, and hobbyists. From local Maker Faires to steampunk conventions, the art of building miniaturized mechanical contraptions is enjoying a revival.

These communities thrive on the exchange of ideas and techniques, echoing the intercultural spirit that once connected a seafaring Dutch trader to a Japanese clockmaker or a Bavarian migrant to the Milwaukee watchmaking scene.

CONTINUING THE TRADITION WITH A SHARED LEGACY

One of the most fascinating aspects of Karakuri automata is how they serve as a reminder that technology can be tactile, accessible, and deeply personal. While modern robotics are often shrouded in proprietary software and intricate electronics, Karakuri automata are open books with their mechanisms laid bare.

That transparency invites curiosity and compels enthusiasts to learn by tinkering. Similarly, Milwaukee’s German artisan traditions, whether in barrel-making, ironworking, or the assembly of fine machinery, teach the value of mastering a craft step by step.

Karakuri automata and Milwaukee’s industrial heritage offer a compelling narrative of cross-cultural resonance. Both are reminders that mechanical wonders are more than just machines. They embody the shared values of precision, artistry, and community spirit. Such values traverse continents and centuries, carried by artisans determined to fuse aesthetics with innovation.

© Photo

Akkharat Jarusilawong, Sanga Park, Nicholas J. Klein, and Vladimir Mulder (via Shutterstock)