The sound of a name is more than just what we hear. Different languages influence how a name is pronounced, but family traditions can attach a special significance to what they represent. For Kyoung Ae Cho, her name is a meaningful symbol of her deep cultural identity.

Cho understood that her name “Kyoung Ae” was hard for most Americans to pronounce. Many Koreans often adopted an English name that sounded close phonetically to their birth name. But for Cho, her name was connected to her Korean roots. She made a deliberate choice to retain it, despite the occasional difficulties it may have caused in an English-speaking environment.

“Kyoung means ‘respect’ and Ae is ‘love.’ So I don’t know if it means I need to respect and love other people, or I need to get respected or loved. Either way, it’s a good thing,” said Cho. “I never planned to be living in America this long. But as time went by, I never thought about changing my name because I didn’t want to confuse people.”

Cho had experienced situations with Korean friends who had adopted English names. It was possible to talk about two different people, without realizing it was the same person – just known by different names.

“Kyoung Ae” has the same meaning whether written in Hangul, the Korean language, or Hanja, Chinese characters used to approximate the phonetics of spoken Korean. Names also play a big role in Korean culture regarding how people are addressed.

Cho’s early years were spent in a small village in South Korea, a place known for its springs and spa resorts. Born in the 1960s, she recalled the unique blend of rural tranquility and the bustling activity around the popular tourist destination.

“The water was very healing, so it wasn’t an isolated place. There were a lot of visitors, but it was a small place,” said Cho. “I had to leave it behind when I moved to Seoul for middle school. I feel fortunate at least to have memories of walking through rice fields to go to my village school, which a lot of my Seoul friends didn’t have. I felt really blessed for the access I had to that kind of nature.”

Cho also had other good memories from her youth, particularly her time growing up with her grandmother’s companionship. Because both parents were working hard to support the home, she formed a close bond with the elder family member.

“My grandmother was a big part of my artistic development,” said Cho. “She taught me how to sew, and I played with her old-fashioned sewing machine before I even started elementary school. That became my play toy.”

Cho also learned a lot from her mother, an independent and strong woman who raised a whole household, in addition to managing restaurants over the years. It meant Cho grew up around food and was able to eat well, with a school lunchbox full of delicious homemade meals. But it left little time for Cho to spend with her mother.

“Both my mom and grandma were strong women who were born in the wrong time,” said Cho. “If they were born now, their careers would have been amazing. They had the best attitude about life.”

Long before Cho was born, her family woke up one morning in 1945 to find that the Japanese occupation of Korea had ended. However, Korea had been divided into two, and they were now living on the Communist side.

Her family did not originally intend to move south. They had already experienced some aspects of Communism, but because they lived in a small town the impact of the government policies was not overwhelming. Then one day they heard rumors of an impending riot in their town. They decided to leave overnight, thinking it would just be temporary. They would not be the only family to flee.

“My parents didn’t pack much, only small bags, and simply locked up the house. The plan was to hide for a day or two. My grandmother even suggested hiding in the barn, not wanting to leave. Fortunately, they convinced her to come along,” said Cho. “By the time they reached the next town, the situation had worsened, and the riot had spread there too. So, my family kept moving further south, step by step. They never returned home to pack more belongings and basically fled empty-handed. It’s incredible to think about that now.”

The Cho family mostly walked all the way from Hwanghae province in the far north. It was a slow journey with elderly grandparents, a newborn baby, and young children among them.

“My mom recalled that they were among the last people to leave. So there was very little to eat since most homes along the way south had already been ransacked by those who came before them,” said Cho. “They were starving, cold, and had no place to sleep. It took about a month for them to reach Seoul. After that, they never returned home.”

It was the dead of winter, and the family did not even have a warm bowl of rice with kimchi to eat. Cho’s older brother was only 2 years old at the time, and even though he was still breastfeeding there was not enough milk for him.

“My mom always felt guilty, worrying that he didn’t get enough nutrition and might not grow up healthy,” said Cho. “But despite everything, he turned out to be quite strong.”

Although Cho was born after the war, the stories of her family’s struggles had a great influence on her. The trauma of war, combined with her family’s courage, would come to influence both her personal and artistic development.

Her family did not share too many details from those dark days, but once in a while they did talk about their experiences. Things like having to walk long distances and crossing a river to escape. Her father’s version of events differed slightly from my mother’s, and her uncles’ stories.

Each of them seemed to have their own perspective, with some a bit biased to show how they did well during that time. But the common thread was that they were fleeing from North Korea to survive. When they finally reached safety, the American army mistook them for hostiles and almost shot them. Cho’s grandfather, who spoke a little English, managed to explain their situation and were eventually provided some food.

Her aunt remembered that they were given a can of peanut butter with a can of jam by the American army, without bread. They had never eaten such types of food. The peanut butter was too thick and greasy for them, and the jam was overly sweet. They could barely eat it, even though they were starving. But hunger won out in the end.

It was a very uncertain time for her family, having to scavenge for anything edible they could discover on the streets. Thankfully, by the time Cho was born the family fortunes had improved.

When she was not spending time with family, television occupied Cho’s attention as she grew up in Seoul. In those days South Korean programs focused heavily on political news. When there was entertainment, the dramas mostly revolved around patriotic themes about young couples finding love while resisting Japanese occupation. Or heroic young men fighting the North to keep their homes safe from the Communists. They were harsh stories, with deeper political messages.

“Even though I never experienced the war firsthand, I had the longest nightmares about it. Growing up, I heard stories from my family and constantly watched dramas about the war, which deeply affected me,” said Cho. “Every time I watched those shows, I would cry. I remember one time, I was in the U.S. during the Fourth of July many years later. When I heard the Air Force planes flying overhead, my heart started racing,” said Cho. “I usually visit South Korea during that time of year, so I hadn’t experienced it before. Suddenly, I panicked, wondering what was happening. It triggered this deep fear in me. It was surprising because I’ve never lived through a war, but I felt this intense anxiety.”

As a child, Cho was always drawn to creating things with her hands, a passion that was nurtured by her grandmother’s teachings. By the time she reached high school, however, academic achievement became her focus, a common theme in South Korean education.

“I always liked to make things, even from a young age. I thought I might become a fashion designer because I liked making clothing. But in high school, my focus shifted heavily to studying, and I didn’t have huge dreams. It was more about getting good grades and passing the entrance exams,” said Cho. “I ended up going to a women’s university in Seoul to study textile fibers. The campus was isolated, so we were very productive, often staying overnight to work on our projects. I wasn’t very politically active, even though there were demonstrations happening at the time. I think my parents, like many of their generation, taught me not to pay attention to those things. So I focused on my studies instead.”

Cho’s creativity began to develop a distinctive style that was heavily influenced by her cultural heritage, while her dedication earned attention. Her work was often described as “Western” by her peers in South Korea, a label that would eventually inspire her to seek further education abroad.

“My parents were incredible. They traveled all over South Korea starting in the 1970s, which wasn’t common for many people at the time,” said Cho. “They taught me the value of seeing the world and learning from different experiences, which I think helped shape my decision to study and live abroad.”

In 1988, just before the Seoul Olympic Games, Cho made the decision to move to the United States to pursue graduate studies. She was 26 years old and thought she was fully aware of the challenges she would face.

“When I first came to America, I noticed that people expressed themselves differently. In Korea, there’s a lot of attention to what’s not said. But in America, you need to be direct. That was something I had to learn, especially coming from a big family where we shared everything and didn’t always need to speak to be understood,” said Cho. “I had to learn that in America, you have to speak up and express your needs directly. That was different from Korea, where sometimes just being quiet and waiting was a way of showing respect. Adapting to that difference was one of the hardest things for me.”

With a great sense of pride, Cho witnessed the gradual rise of Korean culture on the global stage. What began as a trickle of interest in Korean pop culture soon turned into a wave, with K-pop, Korean cinema, and even Korean consumer products gaining international popularity. The cultural recognition was not lost on Cho, who experienced a mix of pride and surprise at how quickly Korean culture was embraced by the world.

“It was amazing to see how Korean culture has spread globally. When I first heard ‘Gangnam Style’ on the radio here in Milwaukee, I realized how far we’ve come. Even things like Korean cosmetics – people now know about them and use them, which I never would have expected when I first moved here,” said Cho. “In some ways, I felt extra proud because I knew it was more than just a fad. South Korea had really made its mark on the world, and it was exciting to see that.”

Despite the cultural differences she experienced in America, Cho found comfort in the similarities between people from different backgrounds. She also discovered that her work, once labeled as “Western” in Korea, fit into the American art scene but was not considered “Western” at all. Her decision to study in the United States was validated, and she quickly established herself as a talented and innovative artist.

“By the time I was fully grown, my personality and mindset were pretty much set, so it was hard to change. I think that makes a difference. I try not to focus too much on differences. I tend to see people as human beings first, regardless of location or appearance. Sometimes, something happens that reminds me, ‘Oh, I look different.’ But generally, I don’t dwell on that, and I think that’s a positive mindset. If more people thought that way, I believe there would be less conflict.”

When she originally arrived in 1988, Cho did not expect to stay in America for very long, three years maybe but not three decades. Now she is a U.S. citizen, which meant she had to give up her South Korean citizenship. Cho still cooks Korean food, speaks the Korean language, and celebrates Korean traditions. Over time she found a way to balance all of her identities – as a woman, a Korean, and an American, even though it could be challenging at times.

“Living in America as someone born in Korea, I eventually became a U.S. citizen. I thought it would make things easier to visit Korea, especially as my parents aged and I needed to visit more often. Immigration laws and visa requirements kept changing, and at the time, there were shorter visit durations without a visa. I figured that becoming an American citizen would simplify things,” said Cho. “But ironically, after I became a citizen, the rules changed again, and it became more complicated for a while. After COVID-19 some of the policies have relaxed.”

Cho said that even though she was seen as an ethnic minority, she had been fortunate never to experience any serious discrimination. She was blessed to be surrounded by open-minded, intellectual, and kind people, so did not face the difficulties that others had. At times she would be reminded of her unique situation, when friends got angry about the discrimination they experienced, and she had little or no personal experience for comparison.

“Of course, we do need to celebrate our differences, but problems arise when groups start to compete over who’s better. I think that’s where things go wrong,” Cho added. “Personally, I think people who feel they’re in a weaker position often find it easier to forgive others, maybe because they have to.”

Lee Matz

Lee Matz and Kyoung Ae Cho

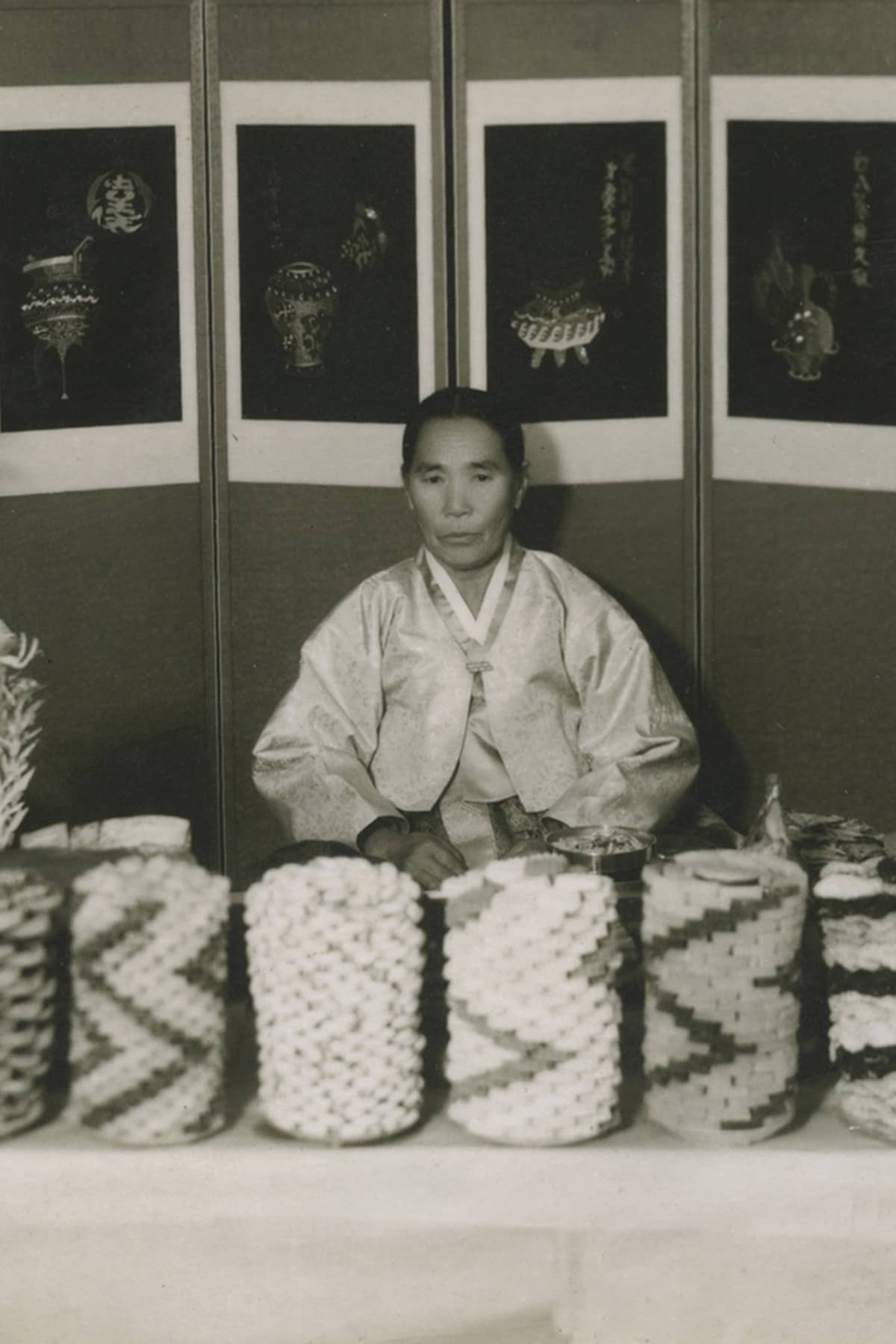

Photo of Cho’s mother and father in 1957. Cho’s grandmother’s 60th birthday in 1964. A group photo of Cho’s family and relatives on her grandmother’s 60th birthday in front of her family’s restaurant. And Cho’s mother and father’s 70th-anniversary photo in 2015.

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora