A mystery persisted for decades surrounding the identity of the pilots flying Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 jets during the Korean War. Reports suggested that the top North Korean pilots were actually from the Soviet Union. Those speculations were further confirmed with the discovery of secret Soviet graves of MiG pilots in China.

It was well known that the Korean People’s Army (KPA) was supplied weapons from Communist benefactors like China and the Soviet Union. But while China’s direct military participation in the war was more clear, the Soviet involvement was murky.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, more Russian veterans began to come forward and acknowledge their illegal participation in the war, specifically dogfight engagements with American jets. Their disclosures finally put to rest the long-standing question of how North Korea was able to deploy a pool of expert aviators.

U.S. Air Force pilots in the Korean War often referred to the skilled MiG-15 pilots as “honchos,” a term derived from the Japanese word “hanchō” (班長) for “squad leader” or “boss.” The true identities of the North Korean pilots were shrouded in mystery.

The unraveling of the Soviet’s secret involvement in the Korean War started in 1989, with revelations in the Soviet press indicating a far more extensive role than previously imagined. Contrary to earlier assumptions that only individual Soviet “volunteer” pilots participated, new information confirmed that Soviet pilots were involved in a significant portion of all MiG-15 engagements against U.S. fighters.

At the onset of the Korean War, the North Korean Air Force was equipped with seventy-eight Yak-9U piston-engine fighters and seventy Il-10 piston-engine attack planes. They were swiftly overwhelmed by U.S. air superiority, due to the inexperience of North Korean pilots.

Once United Nations troops were successful in driving back North Korean ground troops, Beijing and Moscow began consultations for aid to Pyongyang. On October 1, 1950, North Korean leader Kim Il Sung appealed to China’s Mao Zedong for military assistance. Mao agreed and sought Soviet support.

However, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, wary of U.S. strategic air power and the potential for nuclear conflict, was initially reluctant. Although he had promised to help manage the air war, Stalin reconsidered and opted for a more cautious approach.

The Russian dictator eventually provided MiG-15s and limited direct air support, deploying several regiments to the Far East. Despite the commitment, details of high-level Soviet military planning remain scarce, as most modern revelations came from pilots rather than military sources. Stalin likely believed the presence of Soviet aircrews could be concealed.

The first MiG-15 combat patrols in the Korean theater began in November 1950, surprising American aircrews. Although MiG-15s had already been active over Shanghai since April 1950, intelligence had not detected their presence in Korea.

Unlike the regular Soviet Air Forces, the units deployed to Korea were primarily from the elite Air Defense Forces (PVO). They began secret operations from bases in Russian-occupied Manchuria, consisting of regiments equipped with thirty-five to forty aircraft each.

Soviet pilots used their bases in Manchuria to fly covert attack missions, a strategic choice that provided several advantages. The proximity of the bases to the Korean Peninsula allowed for quick deployment and rapid response times, which were crucial for maintaining air superiority and supporting ground operations. Manchuria, under Chinese control but heavily influenced by the Soviet presence, offered a safe haven for the Soviet air units, far from the reach of U.S. bombers.

Following the Yalta Agreement, Soviet forces launched a massive offensive against Japanese-held Manchuria in August 1945, rapidly defeating the Japanese Kwantung Army. The occupation of the entire region was brief, with the Soviets withdrawing by May 1946 and handing over control to the Chinese Communist forces led by Mao Zedong. However, key port cities and tactical military resources remained under Russian dominance until all Soviet troops left in 1955.

The air bases in Manchuria, such as those at Antung, Tungfeng, and Myau-Gou, were well-equipped and strategically located. Soviet regiments shared these facilities with Chinese units, creating a robust network of air support. Antung, the largest Chinese facility, housed a division of Chinese MiG-15s by March 1951, reflecting the integrated collaboration between Soviet and Chinese forces.

In November 1950, U.S. aircrews encountered MiG-15s for the first time. Despite the MiG-15’s technological superiority, the Soviet pilots were initially cautious and inexperienced. The first major engagements saw mixed results, with both sides claiming victories. The arrival of Chinese MiG-15 divisions in December 1950 further complicated the air war.

By early 1951, Soviet and Chinese MiG-15s were actively engaging U.S. forces. Soviet regiments, marked with North Korean insignia, operated under certain restrictions to avoid capture. Despite these precautions, the nationality of the pilots became increasingly apparent, and Soviet pilots eventually flew with their own insignia.

In April 1951, large-scale dogfights erupted over “MiG Alley,” a term used by U.S. pilots for the northwestern region of Korea where these encounters were frequent. The formidable performance of the Soviet pilots forced the U.S. Bomber Command to limit B-29 missions unless heavily escorted by fighters. The MiG-15s soon numbered in the hundreds and posed a significant threat to U.S. air operations.

Despite the growing proficiency of Soviet pilots, the technological balance shifted when the U.S. introduced improved F-86 Sabres and brought a stalemate in aerial superiority. Throughout 1951, Soviet and Chinese forces clashed with U.S. airmen in intense battles, with varying degrees of success.

By September 1951, the combined Communist air forces felt confident enough to plan the deployment of MiG-15 regiments into North Korea, beyond their Chinese sanctuaries. Despite their numerical advantage, the Chinese pilots were less experienced than their Soviet counterparts, leading to a disparity in performance.

The Soviet Union, recognizing the value of the Korean War as a training ground, rotated numerous divisions through the conflict. However, by 1952 the Soviet military leadership was reluctant to deploy the newer MiG-17s to Korea. When the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed in 1953, the U.S. acknowledged 139 air-to-air losses, while Sabre pilots claimed 792 MiG-15s.

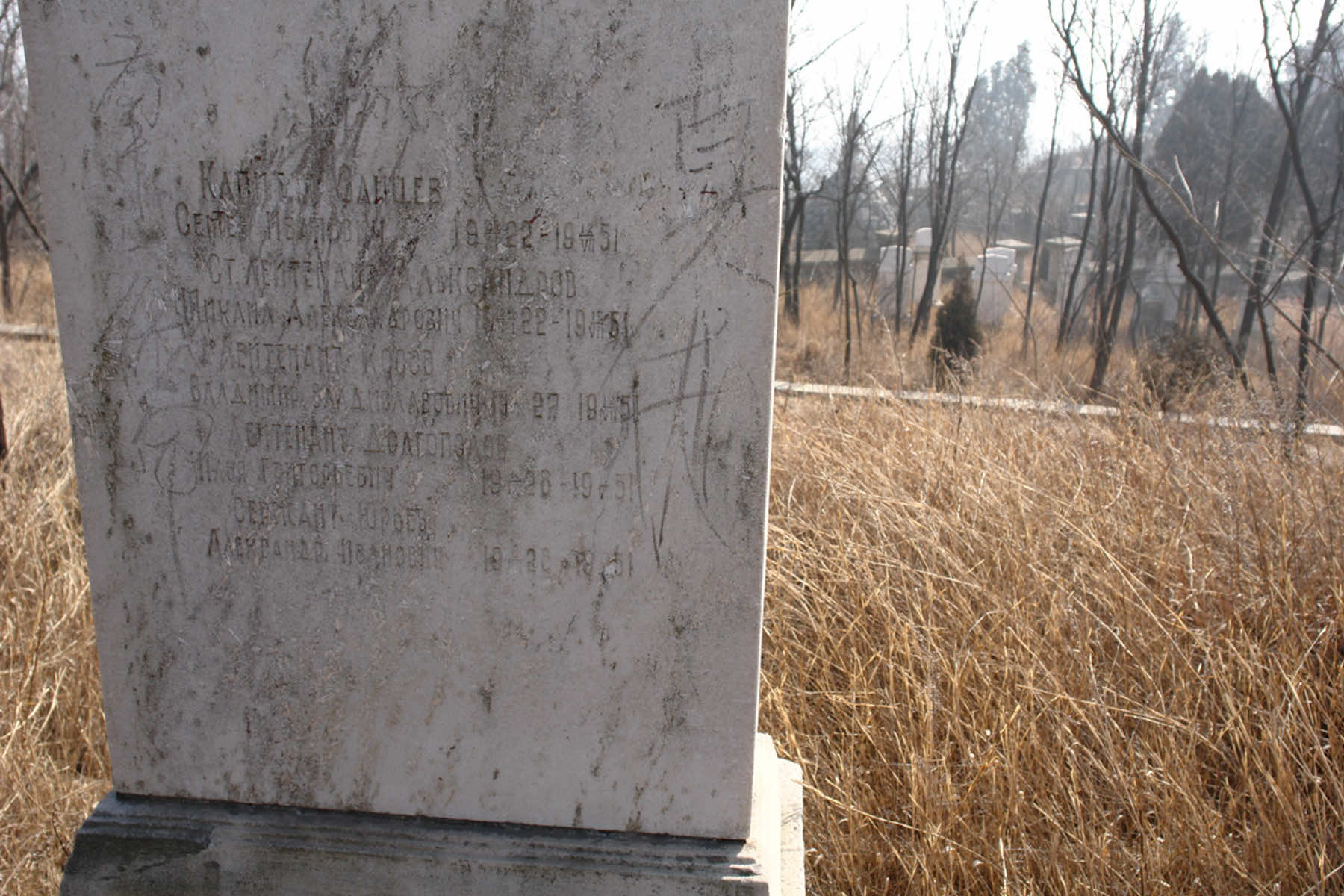

Soviet MiG pilots shot down during the Korean War were buried in Soviet-occupied areas around Liaoning, China. While the Soviets constructed their own military cemeteries on Chinese soil, they also appropriated former Colonial Russian cemeteries from the early 1900s. The graves of children and civilian families can be found in older sections that pre-date the military burials.

The Soviet military made little attempt to hide the graves of MiG pilots interred from 1950 to 1952, adorning headstones with aviation emblems or erecting monuments with aircraft. But over the turmoil of the following decades, which saw China split with Communist Russia and experience an internal Cultural Revolution, the smaller cemeteries were not maintained and fell into disrepair.

More than anything else, the passing of time contributed to how the grave sites were kept secret for so long. When stories of the active Soviet involvement became better known, they coincided with China’s efforts to rehabilitate its global image and whitewash evidence of how it had conspired with Russia.

Both sides maintained secrecy during the Korean War to avoid escalating the conflict into a broader and potentially nuclear war. The Soviet Union concealed its direct involvement to prevent provoking a stronger military response from the United States and to maintain plausible deniability.

The United States, aware of the Soviet pilots, chose not to publicize the information to avoid public pressure for more aggressive military action, which could have led to a dangerous confrontation with the Soviet Union.

With the lack of records, and as memories have faded with the passing of Russian veterans, sites like the graves of Soviet MiG pilots remain as proof of the tactics used in a war that is known best for being forgotten.

MI Staff (Korea)

Lее Mаtz

Shutterstock

These photos were taken in 2008 in Northeastern China. They have never been published or made public until now. The images were kept private in part to protect the site from becoming overrun by Instagram influencers and tourists. But also, because the history of the site still remains sensitive.

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora