“If I hadn’t joined this photoshoot, I don’t think I would have seen the no-go zone with my own eyes. I live in nearby Koriyama, but I didn’t know how devastated this area was until today.” – Mana Ujiie

After the massive earthquake and tsunami, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant suffered three major hydrogen explosions over three days. The devastating chain of events caused an unknown number of deaths, totaling into the thousands. More than 100,000 people were forced to evacuate their homes in the Fukushima Daiichi area.

French photographers Carlos Ayesta and Guillaume Bression were on the ground in the Tōhoku region of Japan in March of 2011, documenting the horrific events that followed the biggest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

Ayesta and Bression spent the following four years trying to answer one question: “What would happen if the nuclear evacuees all returned home at once?”

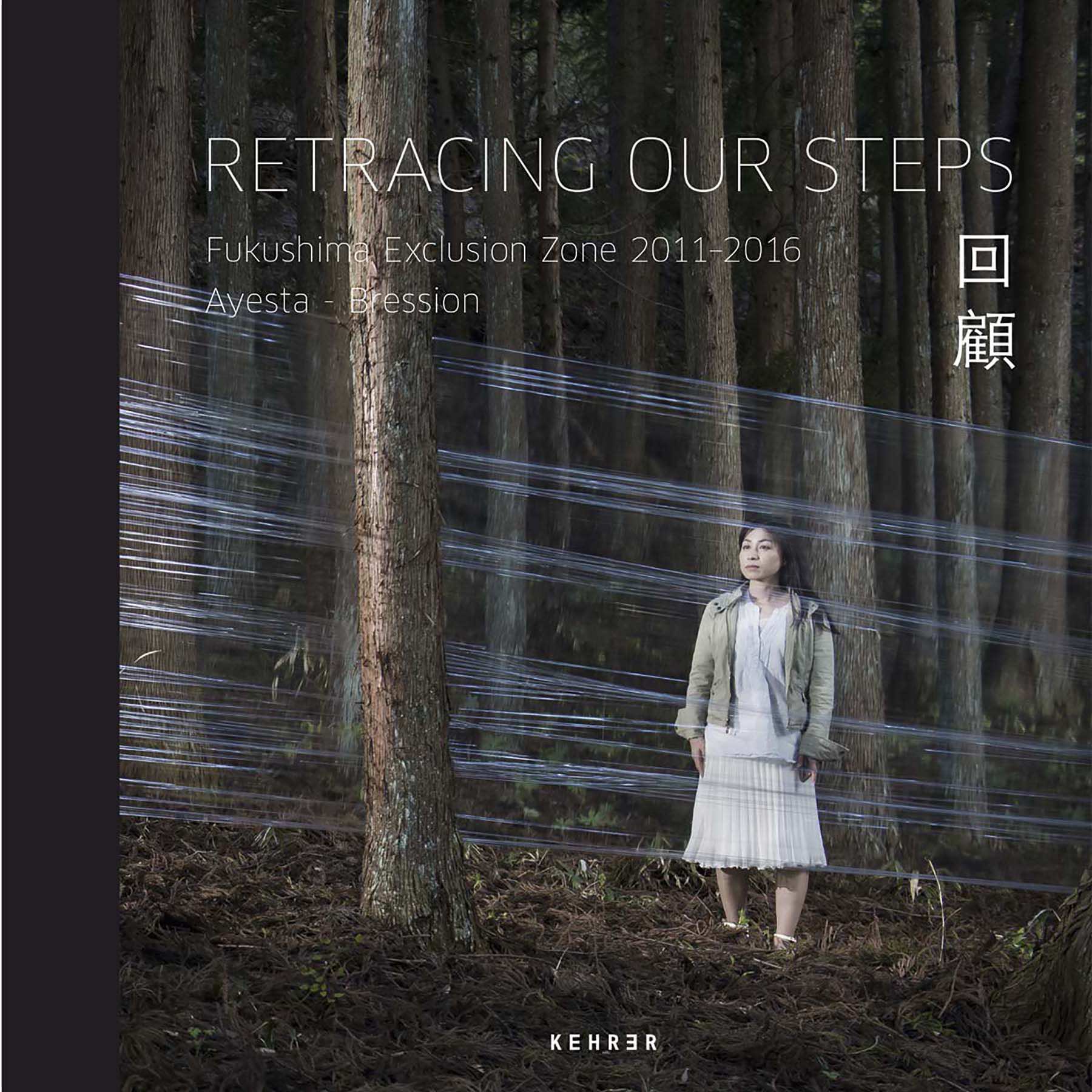

Their multi-year photography project, and the 2016 book Retracing Our Steps: Fukushima Exclusion Zone that was produced as a result of their work, asked former residents or inhabitants from the Fukushima region, and in some cases, the actual owners of certain properties, to join them inside what was then the “no-go zone” and open the doors to the ordinary, but unfriendly, places.

The two French photographers asked some of the 80,000 nuclear refugees forced to evacuate areas near Fukushima to return to the places they once knew, obtaining official permits to actually take them there.

“Facing the camera, they were asked to act as normally as possible – as if nothing had happened. The idea behind these almost surreal photographs was to combine the banal and the unusual. The fact of the historical nuclear accident gives these images a real plausibility,” the artists said in a statement, released when their book was originally published in September 2016.

Many returning residents had felt compelled to return to their homes, schools, and businesses over the years. But once there, they struggled to recognize places once been so familiar to them. Damage from the earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, years of decay from human absence, and the weathering from the elements and animals had rendered the buildings practically unrecognizable.

Now 8 years later, following the 2024 Noto Earthquake, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other man-made disasters around the world, the Retracing Our Steps photographic project deserves revisiting. The haunting visuals stand as a reminder of the fragility of life, and the very long road – perhaps an impossible one – to a recovery that ultimately is only a shadow of the days once considered a “normal” time.

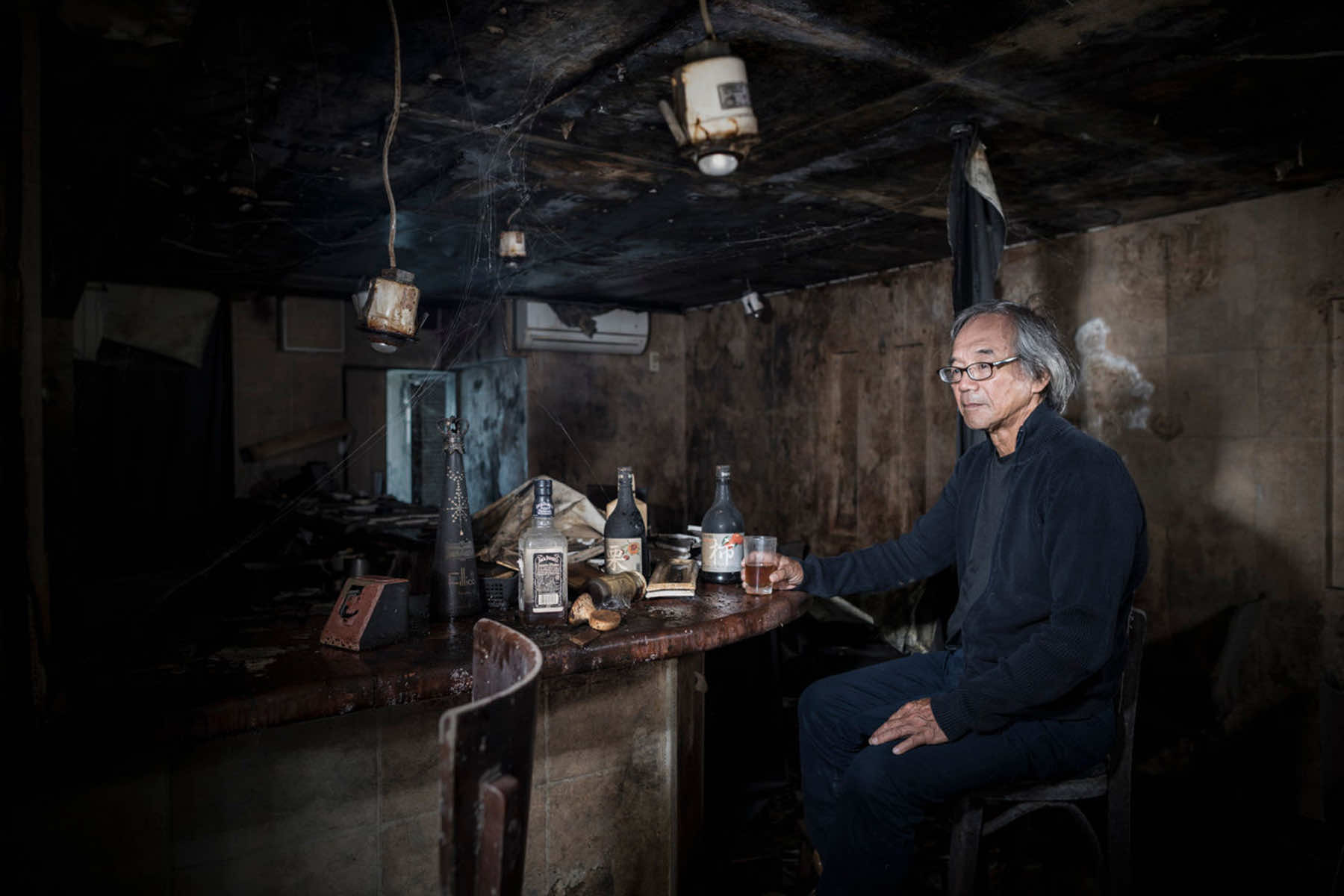

Hiroyuki Igari lives in Iwaki City, 25 miles south of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, and runs a café with his wife. Most of his close friends used to live in the off-limits zones. He is at a Japanese restaurant which was managed by his childhood friend. This restaurant is located 500 yards from the coastline, 5.5 miles from the nuclear plant, and close to Tomioka Station.

In 2014, when this photo was taken in Namie, 4.3 miles from the Fukushima power station, the products in this supermarket had been left in place since the disaster. A native of Koriyama, 37 miles away from the nuclear power station, Midori Ito came to report on the state of the no-go zone.

“My husband and I owned a hairdressing salon in Tomioka, 6 miles away from the power station, until we had to evacuate. Every time I come back here I have the strange feeling that somebody’s come into my place and moved something.” – Keiko Morimatsu

“I’m used to it now, but at first I couldn’t even stay an hour here, in my old printing shop. I didn’t know how to react. I think I thought it wasn’t a place to come back to, even less a place where we could live again. It was a commercial district here. But all my neighbors bought a house somewhere else and nobody plans to return. There are more than 100 million Japanese and more than 10 million inhabitants in Tokyo. In a system where the majority decides, the people from the Fukushima evacuated zone don’t tip the scale. The little town of Namie is a scrap of nothing and nobody would be really worried if it vanished.” – Shigeko Watanabe

This Japanese noodle restaurant is located in the town of Namie, 6 miles away from the nuclear power station. Mangas are piled up on the counter in the foreground.

“I come from the town of Futaba, just 1.2 miles away from the nuclear power station, and I’ve always had a house there. But I’ll never go back to live there. I’ve stayed in the region for work, though, because I manage several supermarkets here. But my whole family left to live north of Tokyo. Like many families from Fukushima, my family has been separated since the disaster.” – Ryoetsu Okumi

“I think my son remembers this house, but my daughter was too young at the time to be able to remember. My wife has only come once or twice since the nuclear accident, as she’s very worried about radioactivity. The first time we returned to our old home, we didn’t say a word to each other. I looked at my wife kneeling on the floor, trying to find things relating to our children, and it broke my heart. That time, the house wasn’t really a mess. But when we came back the second time, the door had been smashed in by a wild boar and the inside of the house had been ravaged. At that moment I thought it’d be impossible for me to come back and live here. Before the nuclear accident, there were no wild boar or monkeys in the region, but since then we often notice these kinds of wild animals every time we visit.” – Shinichi Yamada

“We made tatamis and futons at this house. Three people worked there. I was here when the earthquake struck. The next morning, March 12, we had people walking around our house in radiological protection suits, it was really bizarre. The police said to us, ‘Please evacuate immediately by order of the Prime Minister,’ but they didn’t say where to go. When we evacuated, we thought it would only be for a few days. So we just took medications and blankets. That was all. We came back for the first time on the eve of the total closure of the zone, on April 21, 2011. Back then, we were really scared of radioactivity. When we came back for the first time, I only stayed in the house for 10 minutes. In 10 minutes, in this mess, we had to find everything we valued, it was difficult. There was a strange feeling because the dosimeter was beeping all the time.”– Ikuko Suzuki

Mr. Yasushi Ishizuka is in a pachinko parlor in Tomioka-machi. The building, which was severely damaged from the earthquake disaster, has been left deserted since the accident.

“The main problem is that there are no longer any nurses in the region. They all knew a certain amount about radiology. Most of them evacuated very quickly after the nuclear power station accident and they don’t want to come back. People need to understand that it won’t be the way it was anymore. Elderly people won’t get the support of the younger generation, as was the case before the accident, because there are no more young people in the region. What’s going to become of them without young people in the region? In particular, all the nurses have left and nobody intends to come back … So, will the children come back? One thing is certain, the people coming back today are 70 years old on average, which means they’ll be 80 or 90 in 10 years’ time. If the children don’t come back, we can’t really be talking about revitalization.” – Katsumi Sato

“Before the disaster, I owned a beauty salon in Okuma, 5 km away from the nuclear power station, but I come from the neighboring town of Namie, where this photo was taken. On the day of the seism, I was looking after a client from the Philippines. She was talking to me in perfect Japanese up until the moment the earth began to shake. At that point she began screaming in English, out of panic.” – Rieko Matsumoto

“My grandfather opened this toy store 70 years ago. My family is an important family in the town. There were about 50 of us living in Namie or Odaka and we are all nuclear refugees now. The government reopened the town of Namie in 2017, decontaminating some but not all of the houses. I always worried what would happen if a child went playing around an untreated area …? What the government’s has done did not make any sense for a long time.” – Yuzo Mihara

“After March 11, 2011, proprietors complied with the evacuation order by leaving animals in their enclosures. In the beginning, I didn’t dare set foot on this farm. But three weeks later, I was too worried and I came in. Almost all the cows were already dead or in the throes of agony.” – Naoto Matsumara

“I was born here in Namie, 6 miles away from the nuclear power station, and of course I’d like to go back. Despite the evacuation, I’ve kept my permanent address in Name because, deep down, I’m a resident of Namie, no matter where I go. But as the years have gone by, I’ve ended up telling myself that it’s time to move on because the town will never be the same, everybody’s in the process of buying houses elsewhere.” – Keiko Suzuki

“My father began working as a florist 60 years ago. I inherited it. If there had just been a seism and not a nuclear accident, we would have easily started up our company again, but that’s not the case…” – Toyataka Kanakura

“We are seniors. If anyone decided to come home to the no-go zone, a hospital nearby would be the most important thing for us. Even outside the no-go zone, where we’re refugees, I have to get up at 5 in the morning, the line is so long to see a doctor. If the hospitals don’t reopen in the zone, nobody will come back.” – Tamotsu Hayakawa

“Even if I decided to resume work at the factory, there would be no more activity in my field here. So it would be pointless to come back. I can’t predict the future, but I have the feeling that Namie will become a ghost town where nobody will come back to live. When a survey was first conducted in Namie, only 20% of the people questioned indicated they wanted to come back. As time goes by, this number risks dropping from 20% to 10% and so on. My fear is that Namie could vanish.” – Katsuyuki Yashima

“I remember waiting a long time to get authorization to come home, in the Fukushima no-go zone. There was a long waiting list. When I came back for the first time, I wanted to take lots of things, but because of the radioactivity, we weren’t allowed to take away much. Now I don’t want to come back because it makes me sad to see what my house has become. Before the disaster, I thought my town was the best place to live in, I had everything I needed. Today, I’ve lost all my will to live, I feel so empty. Every time I come here, I feel depressed. I’ve been advised not to come back again. Now I wouldn’t care if somebody robbed my house. There’s not much to steal here, anyway.” – Ayako Hayakawa

This veterinarian set up a business in a bar in the town of Okuma, 3 miles away from the Fukushima power station.

“I left Japan to live in Brazil when I was 30. After March 11, seeing the aftermath of the accident, I decided to come back to help breeders in the Fukushima no-go zone, especially those who had refused to have their livestock slaughtered as the authorities had ordered.” – Toshio Saito

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)