The Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster was a defining moment in Japan’s history.

On March 11, 2011, Japan experienced one of its most devastating natural disasters and the world’s first recorded triple disaster. The event began with a powerful 9.0 magnitude earthquake, the largest to ever hit Japan and the third largest globally since record-keeping began.

The epicenter was located off the Sanriku coast in the Tōhoku region, at a relatively shallow depth of 15 miles beneath the ocean floor. The seismic event set off a massive tsunami. Waves that towered over 32.8 feet high crashed into Japan’s Pacific coastline, stretching over 435 miles and impacting six prefectures.

While the six prefectures in the Tōhoku region and other areas further south were directly affected by the earthquake, the eastern coastal Prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima were most impacted by the devastating tsunami that followed.

The sheer force of the water obliterated towns, severed communication lines, and washed away anything in its path, leaving a trail of destruction and chaos. Compounding the catastrophe was the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant crisis, where the tsunami’s surge overwhelmed the facility’s defenses, leading to the meltdown of three reactors.

The force triggered the release of significant amounts of radioactive material into the environment, marking it as the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. It escalated the situation to a level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, the highest rating denoting a “Major Accident” with widespread health and environmental effects.

The immediate aftermath was horrifying. Nearly 18,300 lives were lost, over 2,500 people were reported missing, and more than 6,000 suffered injuries. Additionally, close to 200,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, leaving hundreds of thousands homeless and leading to an unprecedented economic and humanitarian crisis.

The disaster’s impact was not confined to Japan alone. Repercussions were felt worldwide, emphasizing the global interconnectedness in facing natural and nuclear disasters.

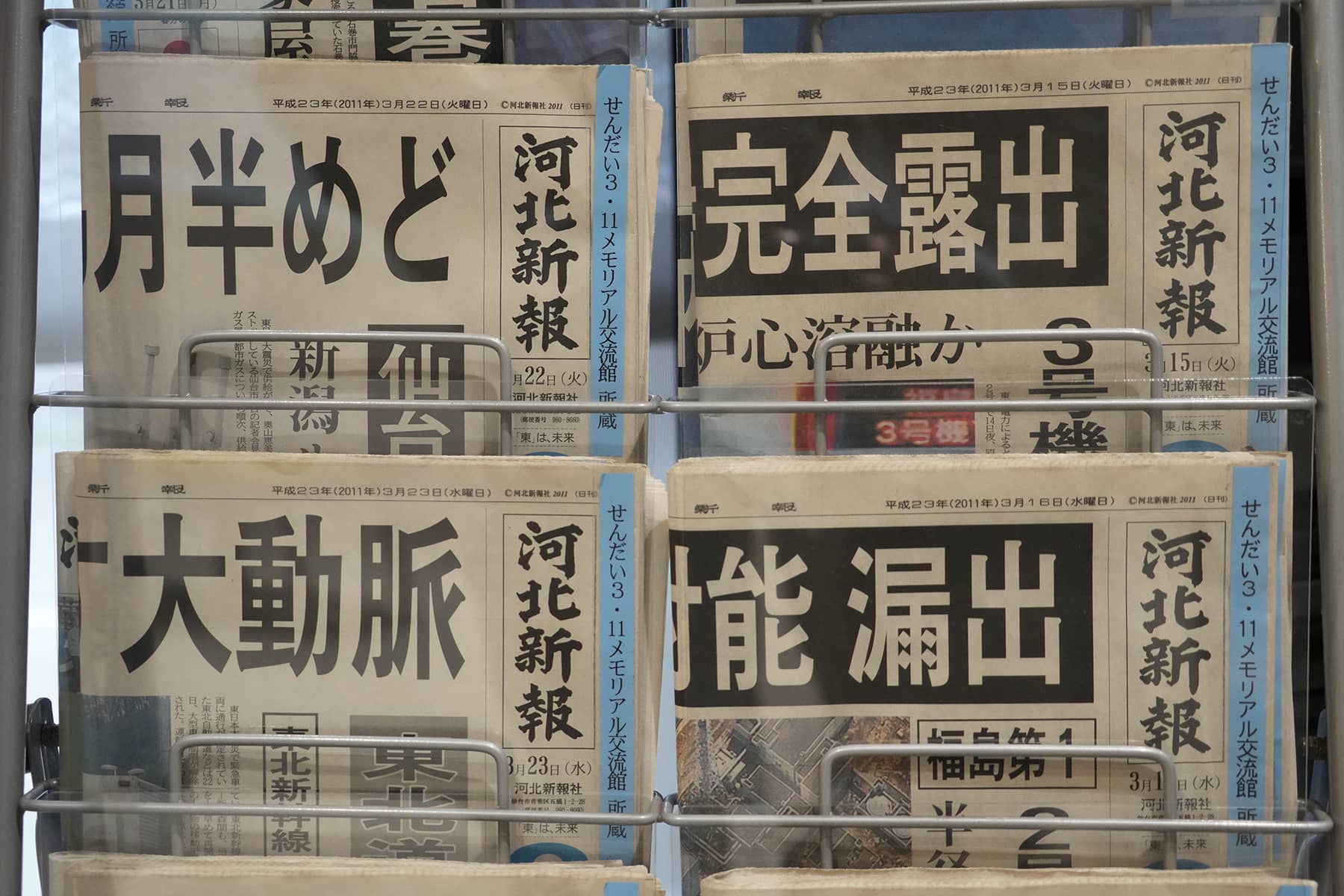

As reported by the Asahi Shimbun on March 4, 2022, a trend has emerged in the years since among municipalities in regions hardest hit by the disaster, particularly a year following the 10th anniversary of the tragic events.

These areas are beginning to reconsider and scale down their annual memorial ceremonies dedicated to the disaster’s victims.

A survey conducted by the Asahi Shimbun involving 35 coastal cities, towns, and villages across the severely affected prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima revealed a changing stance towards the commemoration of the disaster.

Out of those surveyed, only 18 planned to continue with their memorial ceremonies each year. Various reasons were cited for the shift, including the mental health concerns of bereaved families who often speak at these events, as well as a search for alternative ways to honor the memory of those who were lost.

In Miyagi Prefecture where 13 municipalities have historically commemorated March 11 with services, 2023 saw 11 of them forgo any major public events. Onagawa and Shichigahama were among the towns to adopt a more subdued form of remembrance, with the former setting up a flower offering stand and the latter deciding to hold the service less frequently based on feedback from bereaved families.

Cities like Ishinomaki and Higashi-Matsushima, however, plan to proceed with their ceremonies as planned, emphasizing the importance of honoring the victims’ memories. Iwate Prefecture saw a similar mixed response, with 8 municipalities holding memorials in 2023. Only Otsuchi and Kamaishi have had bereaved families speak during their ceremonies, highlighting the ongoing sensitivity around public expressions of grief.

Fukushima Prefecture, despite being the site of the nuclear disaster, had only eight out of ten coastal municipalities conduct memorial events this year. Minami-Soma, significantly affected by the disaster, chose to cancel speeches by bereaved families, a decision driven by the difficulty in finding willing participants amidst concerns about public speaking and media attention.

Some municipalities have explored different methods of commemoration, like Tagajo in Miyagi Prefecture, which has opted for a flower-laying stand to enable broader participation and remembrance. Kesennuma has held a panel discussion focused on disaster memory and preparedness, underscoring the importance of imparting the lessons learned to future generations.

For 2024, many municipalities reconsidered their plans after the January 1 earthquake in Noto renewed public interest in the March 11 anniversary.

March 11, 2024 marked the 13th anniversary of a massive earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster that struck Japan’s northeastern coast. At 14:46 JST, the exact moment that the earthquake occurred in 2011, Milwaukee Independent was in the Futaba District of Fukushima and just over two miles away from the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The following timeline outlines the major events from the onset of the disaster in 2011 through to March 2024, reflecting on the recovery, reconstruction, and ongoing challenges faced by the affected regions.

3.11 Timeline

2011 – March 11

14:46 JST: A magnitude 9.0 earthquake, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan, struck off the northeastern coast, approximately 44 miles east of the Tōhoku region. The earthquake is also one of the top five most powerful earthquakes worldwide since modern record-keeping began.

Shortly after the tectonic event: The earthquake triggered powerful tsunami waves that reached heights of up to 130 feet in some areas. The tsunami devastated coastal areas across the Tōhoku region, washing away buildings, cars, and causing widespread destruction.

15:42 JST: The first tsunami waves reached the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, causing significant damage and leading to the loss of power to the cooling systems of the reactors.

2011 – March 12:

A hydrogen explosion occurred at the plant’s No. 1 reactor, sending radiation into the air. Residents within a 12-mile radius were ordered to immediately evacuate. Similar explosions follow at two other reactors over the following days.

2011 – April 12:

Japan raised the accident to category 7, the highest level on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, from an earlier 5, based on radiation released into the atmosphere.

2011 – April 24:

The government designated a 1.25-mile exclusion zone around the nuclear plant spanning nine municipalities.

2011 – December 16:

After workers struggled for months to stabilize the plant, Japan declared a “cold shutdown,” with core temperatures and pressures down to a level where nuclear chain reactions do not occur.

2012 – December:

The Japanese government declared that the Fukushima plant has achieved a cold shutdown condition, marking a stabilization of the situation.

2012 – July 23:

A government-appointed independent investigation concluded that the nuclear accident was caused by a lack of adequate safety and crisis management by the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, lax oversight by nuclear regulators, and collusion.

2013 – August:

Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) admitted that contaminated water has been leaking into the Pacific Ocean.

2014 – April 1:

The evacuation order was eased for a city west of the wrecked nuclear plant. Parts of at least eight other municipalities were allowed to reopen over the next three years, though the number of returnees remained low due to a lack of jobs and lingering radiation concerns.

2014 – December 22:

TEPCO completed the removal of all spent nuclear fuel rods from the No. 4 reactor cooling pool, an initial milestone in the plant’s decades-long decommissioning.

2015:

Small robots equipped with cameras and sensors were sent into the damaged reactors but provided only limited views of the highly radioactive melted fuel debris. That made plans for its removal more difficult.

2015 – September:

Japan restarted its first nuclear reactor under new safety rules following the Fukushima disaster.

2016 – March:

Evacuation orders begin to be lifted for some villages near the Fukushima plant, allowing residents to return home.

2018 – April:

TEPCO began removing fuel from the cooling pool at Reactor 3, one of the most dangerous operations since the disaster unfolded.

2019 – March:

The government announced plans to release treated radioactive water into the ocean, a decision that sparked international concern and criticism.

2020 – February 10

A government panel recommended the controlled release into the sea of rapidly increasing amounts of leaked radioactive cooling water at the Fukushima plant. TEPCO says its 1.37 million ton storage capacity would be full by fall 2022.

2020 – December 10:

Police said the death toll from the disaster, mostly from the tsunami, reached 18,426, including 2,527 whose remains have not been found.

2020 – December:

The Japanese government allocated additional funds for decommissioning the Fukushima plant and compensating affected businesses, bringing the total cost of the disaster to more than $200 billion.

2021 – February 13:

A magnitude 7.3 earthquake hits off the Fukushima coast, leaving one dead and injuring more than 180 people. It causes minor damage at the nuclear plant.

2021 – March 6:

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga visited Fukushima and pledged to accelerate decontamination efforts so all remaining no-go zones can be reopened but did not give a timeframe.

2021 – March 11:

Japan marked the 10th anniversary of the disaster with nationwide memorials.

2021 – April:

The Japanese government decided to start releasing treated radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean in two years, a plan that received backlash from fishermen, local residents, and neighboring countries.

2022 – February:

A major earthquake hit the Fukushima region, causing damage and injuries, and revived fears about safety among the local population.

2022 – November:

Construction began on an undersea tunnel for the release of treated radioactive water.

2023 – July:

The Japanese government confirmed that the release of treated water into the ocean would begin in the spring of 2024, after final safety checks and approval from international bodies.

2023 – December:

Preparations for the water release included extensive public and international outreach efforts to explain the safety measures and scientific basis for the decision.

2024 – March:

Scheduled commencement of treated radioactive water being released into the Pacific Ocean, marking a significant step in the ongoing Fukushima Daiichi plant decommissioning process.

Future Plans

Work continues on decommissioning the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, a process that is expected to take several more decades.

Throughout the years, Japan has made significant efforts in recovery, rebuilding, and decontamination. However, the events have left an indelible mark on the country, reshaping its energy policy, environmental consciousness, and disaster preparedness strategies. The release of treated water in 2024 is a pivotal moment in what will be a generational effort, reflecting the long-term challenges of managing the aftermath of one of the worst nuclear disasters in history.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

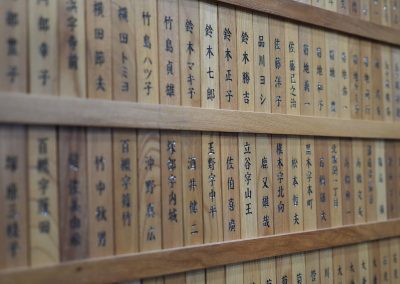

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz

Kotaro Nakatani, Enase, Genza, Yankane, KPG Payless, M. Taira, Falcon Video, AB-Design, Europa Jupiter, Muralonga, and Mkaz328 (via Shutterstock)