Hidden behind a heavy black curtain in one of the nation’s busiest airports is Chicago’s unsettling response to a growing population of asylum-seekers arriving by plane.

Hundreds of migrants, from babies to the elderly, live inside a shuttle bus center at O’Hare International Airport’s Terminal 1. They sleep on cardboard pads on the floor and share airport bathrooms. A private firm monitors their movements.

Like New York and other cities, Chicago has struggled to house asylum-seekers, slowly moving people out of temporary spaces and into shelters and, in the near future, tents. But Chicago’s use of airports is unusual, having been rejected elsewhere, and highlights the city’s haphazard response to the crisis. The practice also has raised concerns about safety and the treatment of people fleeing violence and poverty.

“It was supposed to be a stop-and-go place,” said Vianney Marzullo, one of the few volunteers at O’Hare. “It’s very concerning. It is not just a safety matter, but a public health matter.”

Some migrants stay at O’Hare for weeks, then are moved to police stations or manage to get into the few shelters available. Within weeks, Chicago plans to roll out winterized tents, something New York has done.

Up to 500 people have lived at O’Hare simultaneously in a space far smaller than a city block, shrouded by a curtain fastened shut with staples. Their movements are monitored by a private company whose staff control who enters and exits the curtain.

Sickness spreads quickly. The staffing company provides limited first aid and calls ambulances. A volunteer team of doctors visited once over the summer and their supplies were decimated.

Chicago offers meals, but only at specific times and many foods are unfamiliar to the new arrivals. While migrants closer to Chicago’s core have access to a strong network of volunteers, food and clothing donations at O’Hare are limited, due to airport security concerns.

Most of the 14,000 immigrants who have arrived in Chicago during the last year have come from Texas, largely under the direction of Republican Governor Greg Abbott.

As more migrants arrived, the city’s existing services were strained. Officials struggled to find longer-term housing solutions while saying the city needed more help from the state and federal governments. Brandon Johnson took office in May and has proposed tents.

Many migrants are from Venezuela, where a political, social and economic crisis in the past decade has pushed millions of people into poverty. At least 7.3 million have left, with many risking an often-harrowing route to the United States.

Maria Daniela Sanchez Valera, 26, who passed through Panama’s dangerous, jungle-clad Darien Gap with her 2-year-old daughter, arrived at O’Hare in early October. She fled her native Venezuela five years ago for Peru, where her daughter was born. After her daughter’s father was killed, she left.

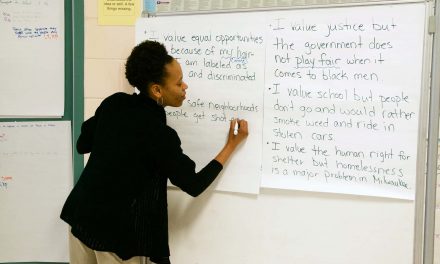

“We come here with the intention of working, not with the intention of being given everything,” she said. A recent Biden Administration plan to offer temporary legal status status, and the ability to work, to Venezuelans doesn’t apply to her because she arrived after the deadline.

She tries to keep the toddler entertained with walks around the terminal. On a recent day, a staff member told Valera to make her daughter stop running or else they would be kicked out. The company, Favorite Healthcare Staffing, said employees treat new arrivals with respect and it would investigate further.

Valera said she wanted to take a train from the airport, but she didn’t have the roughly $5 subway fare. “There are many people who have been able to get out and they say that in the garbage dumps you can get good clothes for the children,” she added.

Chicago began using the city’s two international airports as temporary shelters as the number of migrants arriving by plane increased. Nearly 3,000 people who have arrived by plane since June have sought shelter.

A handful live at Midway International Airport. When they need clothes or services, they walk 2 miles (3 kilometers) to a police station, volunteers say.

At O’Hare, migrants have spread out beyond the curtain for more space, sleeping along windows. Travelers wheeling suitcases and airline staff catching buses whiz by, some stopping to take pictures.

Chicago officials acknowledge using O’Hare isn’t ideal, but say there aren’t other options with a crisis they inherited.

Cristina Pacione-Zayas, first deputy chief of staff, said Chicago is slowly building capacity to house people. The city has added 15 shelters since May and resettled about 3,000 people. They serve 190,000 meals weekly and partner with groups for medical care, but still rely heavily on volunteers to fill gaps.

“Is it perfect? No. But what we have done is stood in our values to ensure that we live up to operationalizing a sanctuary city,” she said. “We will continue to work on it, but we are holding the line.”

Other cities oppose using airports. At Boston’s Logan International Airport, migrants who arrive overnight are given cots for a few hours before being sent elsewhere. Massport spokeswoman Jennifer Mehigan said Logan “is not the appropriate place” to stay.

When reports of a possible federal plan to use the Atlantic City International Airport in New Jersey as a shelter surfaced recently, elected officials blasted the idea.

“It is such a preposterous solution to the problems we have,” said Atlantic County Executive Dennis Levinson. “Who is going to secure these people? Who is going to feed them? Who is going to educate them? We really don’t have any infrastructure to take care of them.”

Jhonatan Gelvez, a 21-year-old from Colombia, didn’t plan to stay at O’Hare long, as he has a friend in Chicago. He teared up when he talked of being separated from his fiancé en route to the U.S. Among his few belongings was a silver, anchor-shaped necklace she gave him.

“Just by arriving here I feel peace,” he said. “It is a country with many opportunities. … I am very grateful.”

Yoli Cordova, 42, also arrived at O’Hare in early October. She left Venezuela because she was discriminated against for her sexual orientation. She cried as she expressed relief at leaving but remained worried about her daughters in Venezuela.

“I don’t know if they’re going to help me here,” Cordova said. “I really don’t know what to do, where to go.”