The voice of Martin Luther King Sr., a melodic tenor like his slain son, carried across Madison Square Garden, calming the raucous Democrats who had nominated his friend and fellow Georgian for the presidency.

“Surely, the Lord sent Jimmy Carter to come on out and bring America back where she belongs,” the venerated Black pastor said as the nominee smiled behind him. “I’m with him. You are, too. Let me tell you, we must close ranks now.”

Carter then shared a moment with Coretta Scott King, clasping hands and locking eyes with the widowed first lady of the Civil Rights Movement, their children looking on.

For the Kings, closing the 1976 convention affirmed their continued reach — and their pragmatism — eight years after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. For Carter, it marked the evolution of a White politician from the Old Confederacy: As a local leader and state senator who aspired for more, he had mostly avoided controversial stands during the civil rights era. During all their years in Atlanta, he never met the movement’s leader.

“Carter never did anything racist himself. But he didn’t participate,” biographer Jonathan Alter said. “And King was right there.”

Yet the alliance Carter later forged with the King family endured as he grew into a governor, president, and global humanitarian who advanced racial equality and human rights.

“He was one of the few presidents who really was an advocate for the Black community out of a pureness of heart,” said the Rev. Bernice King, who leads the King Center that her mother founded.

Now 98, Carter is receiving hospice care in Plains, Georgia. King, just 39 when he was gunned down in 1968, would have been 94.

Certainly, King would have expanded his own legacy with a longer life span — after civil rights victories for Black Americans he turned his focus to challenging Western militarism and rapacious capitalism — and there’s no way to know what kind of relationship King might have had with Carter once the Georgia Democrat reached high office.

As it was, Carter used the most visible decades of his public life to reflect King’s values and often his rhetoric, while playing a central role in memorializing King as an American icon.

Carter opened government contracts to Black-owned businesses and appointed record numbers of Black citizens to executive and judicial posts. He steered more public money to historically Black colleges and opposed tax breaks for discriminatory private schools. He echoed King’s emphasis on peace, expressing pride long after his presidency that he never started a shooting war.

Carter quoted many of the same theologians King cited in his practice of nonviolent resistance, and he would join King in 2002 as a Nobel Peace Prize winner. As a former president, Carter tracked King’s later economic observations, declaring the U.S. an oligarchy, rather than a fully functioning democracy, because of wealth inequality and money in politics.

That record, Bernice King told The Associated Press, cements Carter as a “courageous” and “principled” figure who built on her father’s work, while having “genuine” relationships with her mother and grandfather.

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter welcomed the Kings to the White House to present Coretta with a posthumous Medal of Freedom for her husband, making him one of the few Black Americans to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor at that point. Carter helped establish government observances of King’s birthday and enabled the federal historic site encompassing King’s birthplace, burial site and the family’s Ebenezer Baptist Church.

The former president even served as private mediator for King’s children, helping settle an extended dispute over their parents’ estate. “I appreciate his efforts” ending the highly publicized fight, Bernice King said.

Barely 5 years old when her father was killed, the younger King said she does not “know for sure” when the families’ friendship began. She thinks her mother made the first overture, after Carter became Georgia governor in 1971.

“My mother was the kind of leader who made sure that she connected with the people she felt could assist her in the work that she was doing to continue my father’s legacy,” King said.

It had not been obvious before Carter reached statewide office that he could be such a partner.

During the peak of the Civil Rights Movement, as Martin Luther King Jr. worked with President Lyndon Johnson on the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, Carter was a one-term state senator. He supported Johnson’s election in 1964 and never aligned with segregationist colleagues in Atlanta, but Carter didn’t speak out in favor of the federal laws during his two campaigns for governor, nor did he appear at Ebenezer, just a few blocks from the Georgia Capitol.

When King was assassinated, Carter did not attend the funeral. In 1970, he won the governor’s race as a conservative Democrat, avoiding explicit mentions of race while assuring voters of his general preference for “local control” over federal intervention.

A “code-word campaign,” Alter called it.

Then, at his inauguration, the 46-year-old Carter issued a surprise edict: “The time for racial discrimination is over.”

Bernice King assessed his declaration as “very profound at the time.”

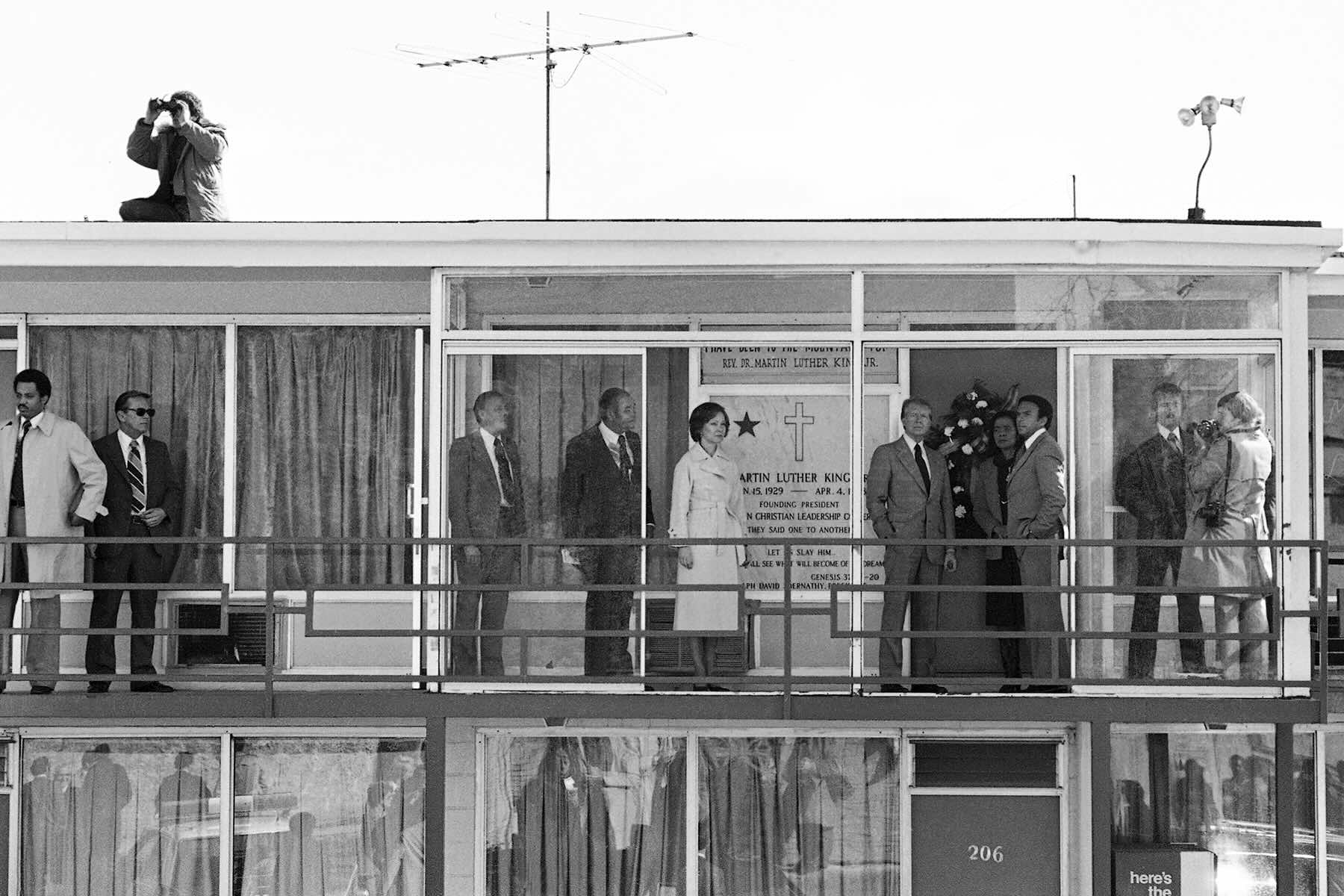

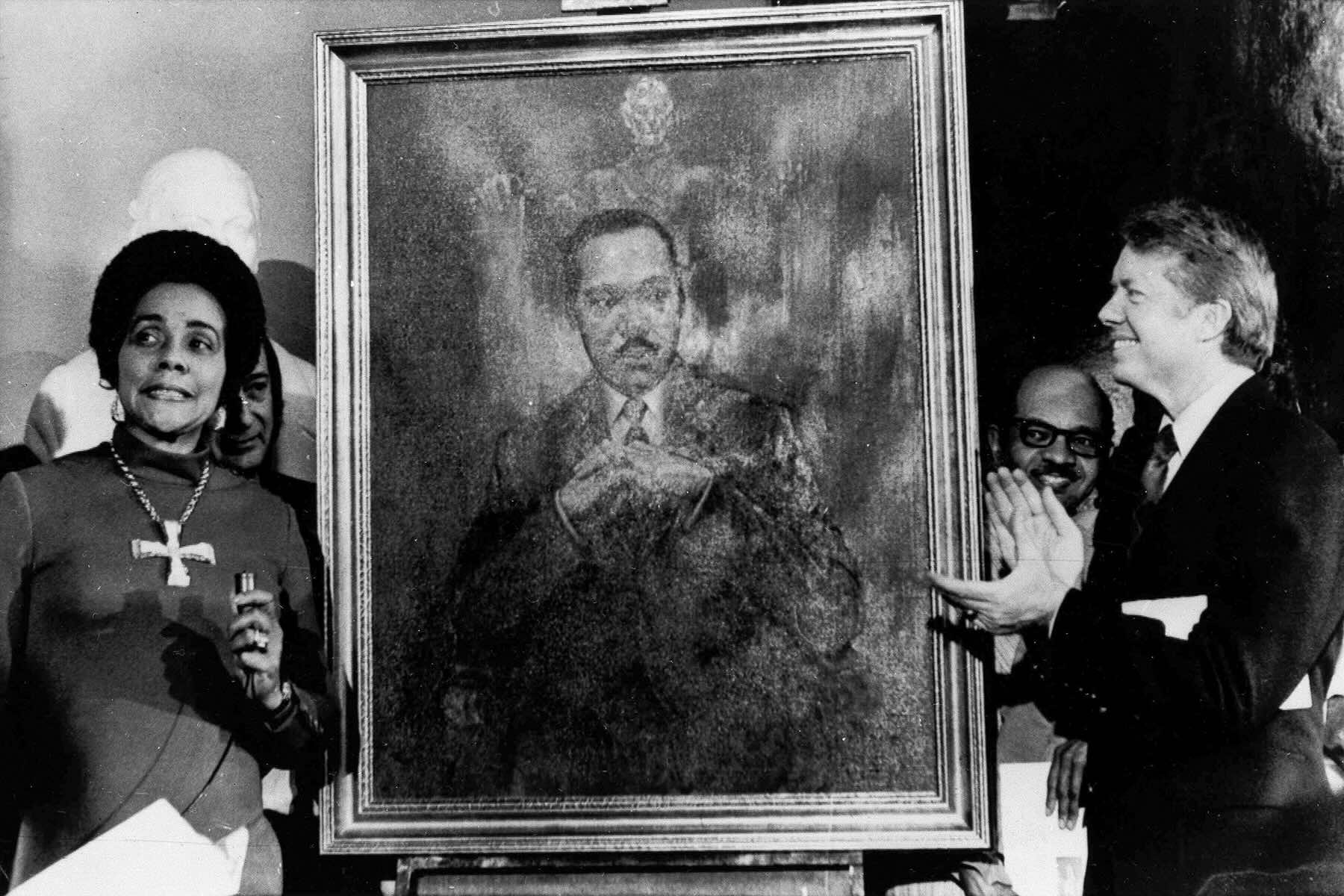

Within a few years, Carter stood with the King family in the Georgia Capitol as Coretta unveiled a portrait of King, while Ku Klux Klan members protested outside.

King Sr. had no trouble reconciling Carter’s earlier maneuverings before reaching the governor’s seat.

“He had never been characterized as a ‘cracker’ lawmaker, the way so many rural statesmen had been,” the elder King wrote in his autobiography.

He said Carter “achieved an unusual reputation” among Black constituents with his “willingness to meet with people and work long hours on issues and needs.”

Such attention showed the way for Democrats as expanded voting rights finally allowed Black voters to flex political power. Every Democratic president since then has depended on strong Black support to win the nomination and general election. President Joe Biden has recognized the dynamics by pushing the national party to put more diverse states, including Georgia, earlier in the nominating process.

Political calculations aside, Bernice King said her grandfather and Carter shared “real kinship” as two Baptists raised in small-town Georgia. The senior King once described their conversations as “one country boy to another.”

Carter paid the elder King an in-person visit to ask for his support at the outset of his presidential bid. Never a party loyalist, the elder King initially told Carter he would support his White House bid only if Republican Vice President Nelson Rockefeller did not run again. King’s reasoning: Carter was a longshot, while Rockefeller, a civil rights liberal, was already a heavyweight.

When it became clear Rockefeller would not be President Gerald Ford’s running mate in 1976, King endorsed Carter. It was an invaluable imprimatur for a white Southern governor from the same generation as segregationists like Alabama’s George Wallace and Georgia’s Lester Maddox.

King vouched for Carter in Black churches across the country and to the nearly all-white national press corps, particularly after Carter mangled federal housing policy discussions by defending “ethnic purity” in American neighborhoods.

Carter tried to clean up his remarks with more explanations, saying he would “oppose very strongly and aggressively” any “exclusion of a family because of race or ethnic background” but still saw it as “good to maintain the homogeneity of neighborhoods if they’ve been established that way.”

Carter eventually followed with an apology.

Bernice King said her grandfather saw Carter’s word choices as “an innocent mistake” and urged journalists and voters to see Carter’s values and full record.

During the first half of Carter’s long life, “he had to navigate in a society, in a culture where, as a white person, you were expected to hate and see Black people in a very demeaning way,” Bernice King said. Considering the whole of his life, she said, “I think he managed that very well.”

Along the way, Carter learned something the King siblings and cousins always understood about their grandfather and that “booming” voice.

“When Granddaddy opened his mouth,” Bernice King said, “you paid attention.”