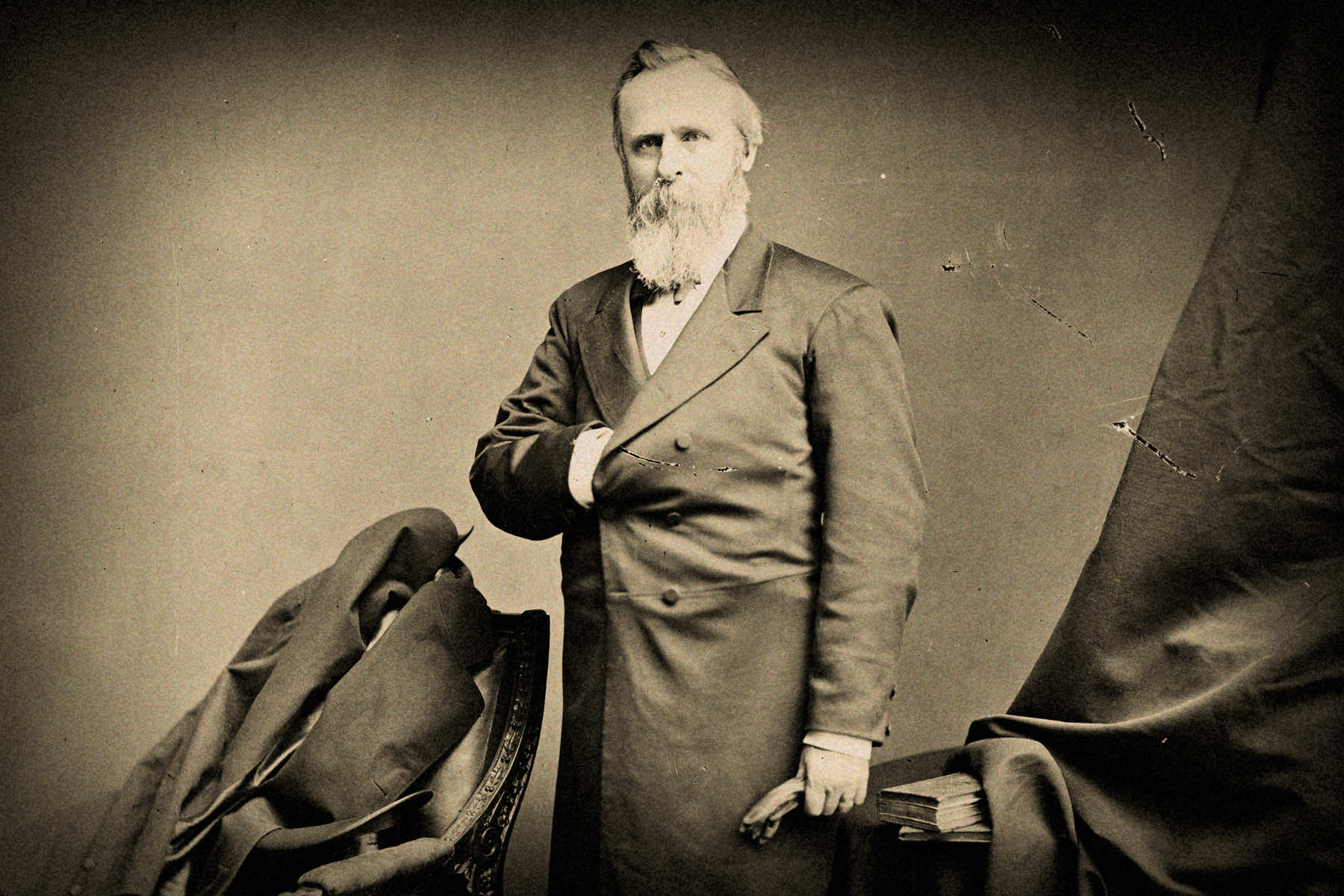

It is commonly understood that Republican Rutherford B. Hayes won the electoral votes from three contested southern states in 1876 and thus took the presidency by promising to remove from the South the U.S. troops that had been protecting Black Americans there. Then, the story goes, he removed the troops in 1877 and ended Reconstruction. But that is not what happened.

On March 2, 1877, at 3:50 in the morning, the House of Representatives finally settled the last question of presidential electors and decided the 1876 election in favor of the Republican, Rutherford B. Hayes, just two days before the new president was to be sworn in.

The election had been bitterly contested. Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden appeared to have won the popular vote by about 250,000 votes, but broken ballot boxes and terrorized Black voters in three southern states made it clear the count was suspect. A commission of fifteen lawmakers tried to judge which of the dueling slates of electors from those states were legitimate. In the end, the commission, dominated by Republicans, decided the true electors belonged to Hayes.

To make sure the southerners who were threatening civil war over the election did not follow through, leading industrialists and lawmakers made promises to southern leaders that a Republican president would look favorably on federal grants to southern railroads and would not fill government positions with Republicans in the South, giving control of patronage there to a Democrat.

But what did not happen in 1877, either before or after the inauguration, was the removal of troops from the South.

That legend came from a rewriting of the history of Reconstruction in 1890 by fourteen southern congressmen. In their book Why the Solid South? Or Reconstruction and Its Results, they argued that Black voting after the Civil War had allowed Black people to “dominate” white southerners and virtually bankrupt the region and that virtuous white southerners had pushed them from the ballot box and “redeemed” the South. Contemporaries had identified the end of Reconstruction as 1870, with the readmission of Georgia to the United States. But Why the Solid South identified the end of Reconstruction as the end of Republican rule in each state.

In 1906, former steel baron James Ford Rhodes gave a date to that process. In his famous seven-volume history of the United States, he said that in April 1877, Hayes had ended Reconstruction by returning all the southern states to “home rule.” In his era, that was a political term referring to the return of power in the southern states to Democrats, but over time that phrase got tangled up with what did happen in April 1877.

During the chaos after the election, President U.S. Grant had ordered troops to protect the Republican governors in the Louisiana and South Carolina statehouses. When he took office, Hayes told Republican governors in South Carolina and Louisiana that he could no longer let federal troops protect their possession of their statehouses when their Democratic rivals had won the popular vote.

Under orders from Hayes, the troops guarding those statehouses marched away from their posts around the statehouses and back to their home stations in April 1877. They did not leave the states, although a number of troops would be deployed from southern bases later that year both to fight wars against Indigenous Americans in the West and to put down the 1877 Great Railroad Strike. That mobilization cut even further the few troops in the region: in 1876, the Department of the South had only about 1,586 men including officers. Nonetheless, southerners fought bitter congressional battles to get the few remaining troops out of the South in 1878–1879, and they lost.

The troops did not leave the U.S. South in 1877 as part of a deal to end Reconstruction.

It matters that we misremember that history. Generations of Americans have accepted the racist southern lawmakers’ version of our past by honoring the date they claimed to have “redeemed” the South. The reality of Reconstruction was not one in which Black voters bankrupted the region by taking tax dollars from white taxpayers to fund roads and schools and white voters stepped in to save things; it was the story of an attempt to establish racial equality and the undermining of that attempt with the establishment of a one-party state that benefited a few white men at the expense of everyone else.

Certain of today’s Republican leaders are engaged in an equally dramatic reworking of our history.

When Florida governor Ron DeSantis last March signed the law commonly called the “Don’t Say Gay” law, he justified it by its title: the “Parental Rights in Education” law. It restricted the ability of schoolteachers to mention sexual orientation or gender identity through grade 3, and opponents noted that its vagueness would lead teachers to self-censor.

Under the guise of protecting children, DeSantis echoed authoritarians like Hungary’s Victor Orbán and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who claim that democracy’s principle that all people are equal—including sexual minorities—proves that democracy is incompatible with traditional religious values. Promising to take away LGBTQ Americans’ rights offered a way to consolidate a following to undermine democracy.

DeSantis sought to shore up his position by mandating a whitewashed version of a mythic past. At his request, in March the Florida legislature approved a law banning public schools or private businesses from teaching people to feel guilty for historical events in which members of their race behaved poorly, the Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees (Stop WOKE) Act.

In July the Florida legislature passed a law mandating that the books in Florida’s public school cannot be pornographic and must be suited to “student needs”; a state media specialist would be responsible for approving classroom materials. An older law makes distributing obscene or pornographic materials to minors a felony that could lead to up to 5 years in prison and a $5,000 fine. Unsure what books are acceptable and worried about penalties, school officials in at least two counties, Manatee and Duval, directed teachers to remove books from their classrooms or cover them until they can be reviewed.

In January, DeSantis set out to remake the New College of Florida, a public institution known for its progressive values and inclusion of LGBTQ students, into an activist Christian school. He replaced six of the college’s thirteen trustees with far-right allies and forced out the college president in favor of a political ally, giving him a salary of $699,000, more than double what his predecessor made.

On February 28, right-wing activist Christopher Rufo, the man behind the furor over Critical Race Theory and one of DeSantis’s appointees to the New School board, tweeted: “We will be shutting down low-performing, ideologically-captured academic departments and hiring new faculty. The student body will be recomposed over time: some current students will self-select out, others will graduate; we’ll recruit new students who are mission-aligned.”

Then, at the end of January, the board voted to abolish diversity, equity and inclusion programs at the school. DeSantis has promised to defund all DEI programs at public colleges and universities in Florida.

The attempt to take over schools and reject the equality that lies at the foundation of liberal democracy is now moving toward the more general tenets of authoritarianism. At the beginning of March, one Republican state senator proposed a bill that would require bloggers who write about DeSantis, his Cabinet officers, or members of the Florida legislature, to register with the state; another proposed outlawing the Democratic Party.

DeSantis and those like him are trying to falsify our history. They claim that the Founders established a nation based on traditional hierarchies, one in which traditional Christian rules were paramount. They insist that their increasingly draconian laws to privilege people like themselves are simply reestablishing our past values.

But that’s just wrong. Our Founders quite deliberately rejected traditional values and instead established a nation on the principle of equality. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” they wrote, “that all men are created equal.” And when faced with the attempt of lawmakers in another era to reject that principle and make some men better than others, Abraham Lincoln called it out for what it was. “I should like to know,” he said, “if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop?”

To accept DeSantis’s version of our history would be a perversion of our past and our principles. But it is not unimaginable. The troops did not leave the South in 1877.

Everett Collection

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics