Art is at the core of what makes us human. Yet to many, engagement with the arts seems inaccessible. In the elaborate game of chess that is the tangible art market, the movements of players including gallerists, critics, collectors, and prospectors can make purchasing art seem more akin to trading on the stock market rather than something done in response to an emotional connection.

While museums serve to democratize access to art, even these public spaces can be paradoxically perceived as exclusive due to the means by which their collections are assembled, and how those collections are interpreted. Although historically associated with the rich and powerful, the act of collecting art is not out of reach for those outside of elite circles today – if people know where to look.

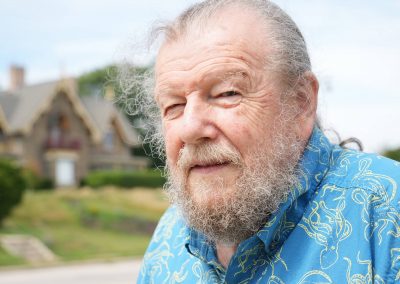

Within our own local community there are a number of artists not valued highly enough. Many of them, for one reason or another, never stepped on that chessboard to truly participate in an art market often defined by the tastes of a select few. One such underappreciated artist in Milwaukee, whose works would fit oh so naturally within the permanent collection of any white-walled art museum, is Michael Kutzer.

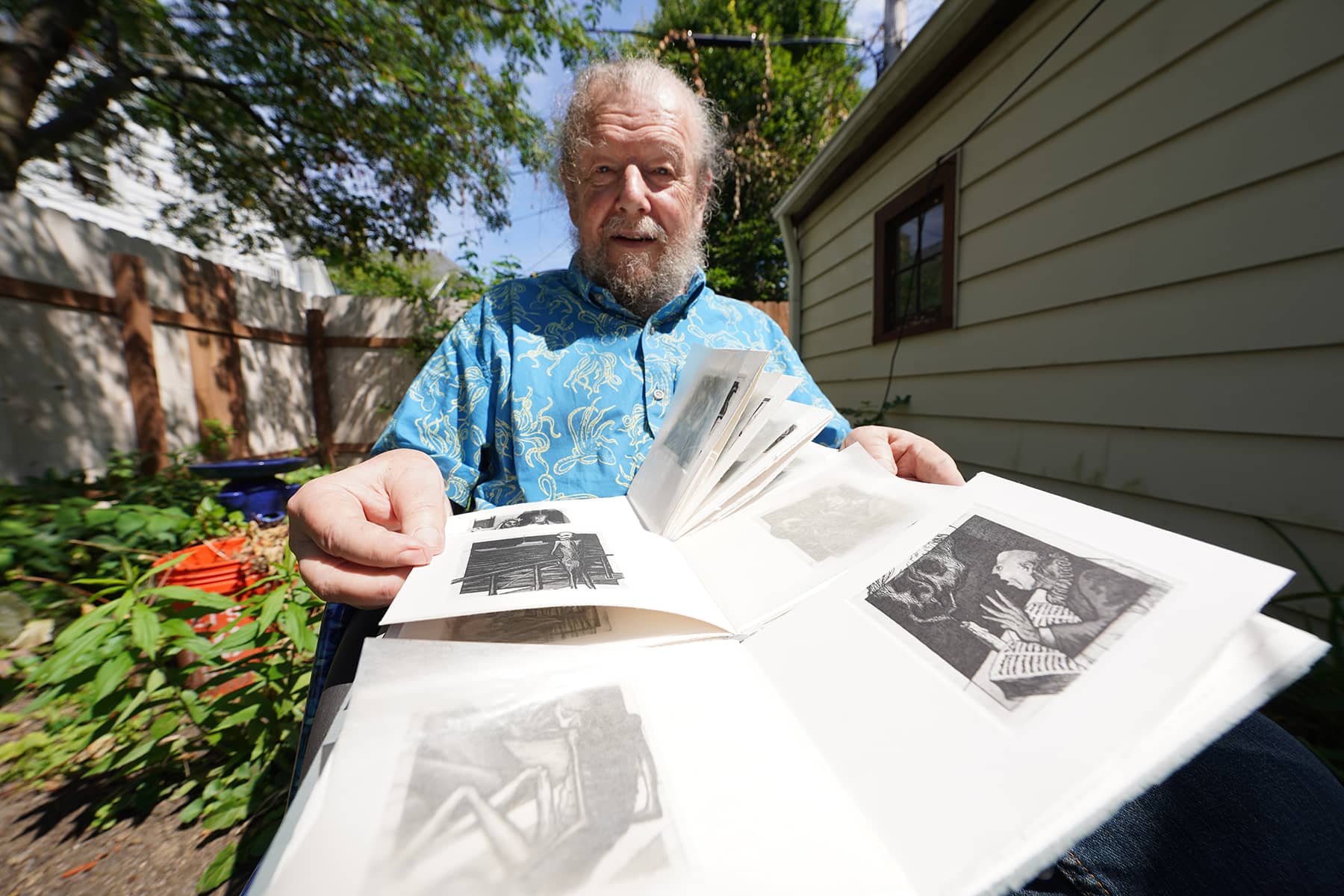

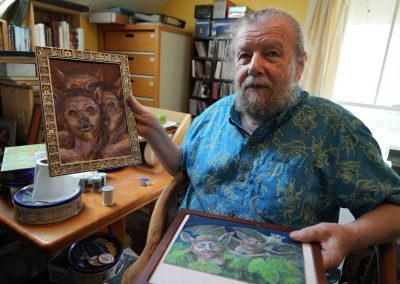

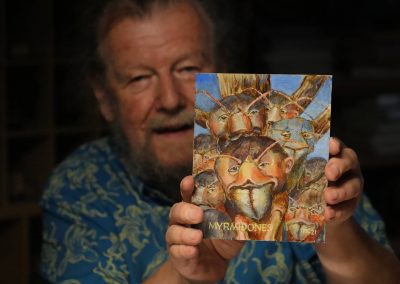

Kutzer, an artist in his eighties who emigrated from Germany to Milwaukee in 2005, creates artworks inspired by his environment, Western mythology, and his profound imagination. His paintings and etchings vary in style and emotional character, portraying anything from Boschian anthropomorphs to serene Lake Michigan seascapes.

Like any great artist, years of honing his craft combined with a unique self-expression that emerged during different chapters in his life has created a wide breadth of work. For an artist of such talent, with an extraordinary collection, it seems baffling that his art is not more widely recognized within his adopted city.

Nourished by his painter father and a love for mythologized ages of the past, Kutzer formulated his own approach to artmaking long before his move to Milwaukee. Although he learned the foundational techniques of painting from his father, it was not his father’s idealized landscapes which first lured him to the canvas. Instead, the studies and pastimes of his youth set the stage of a wondrous world in which the lines between fantasy and reality blurred.

In his formative years he attended a school which emphasized Classical studies, learning Latin and Greek and absorbing the cultures and lores of ancient times. Beyond the Classical world, that of Medieval Europe also played an important role in Kutzer’s development. Not only was he a voracious reader of its sagas and legends, but he regularly visited places like Gottorf Castle with its collection of knightly attire and mummified bog bodies. Or the Viking walls of Haithabu near where sunken ships lay, engrossing the imaginations of adolescent explorers.

Kutzer described his early days of painting and etching as a “process of liberation from the dominant shadow of my father. The terrible experiences of WWII had made him a painter of nature and harmony avoiding the human body and focusing on the beauty of animals, flowers, and landscapes. To find my own way, I had to avoid these subjects and turned to subjects of my childhood, painting ruins or painting fantasies under the influence of Pieter Bruegel or Hieronymus Bosch.”

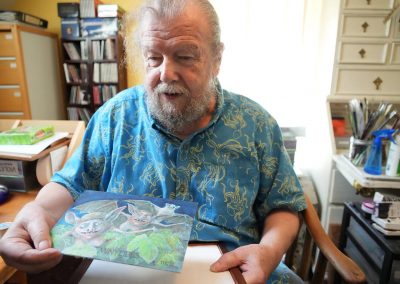

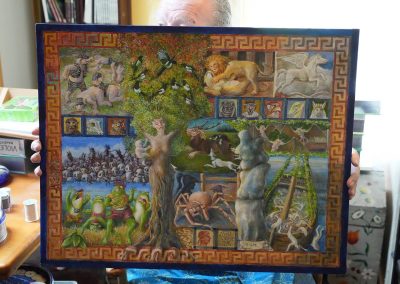

Indeed, any admirer of Bruegel or Bosch would immediately recognize the similarities from the mischievous faces in Kutzer’s Punch and Judy woodcut prints to the frequent use of mollusks in beautiful yet dystopian scenes. Such dualities of theme appear regularly, with shelled sea creatures often serving a central symbolic role. As Kutzer sees it, they “told stories of decay and death, but broken snail houses also could symbolize shelter and protection.”

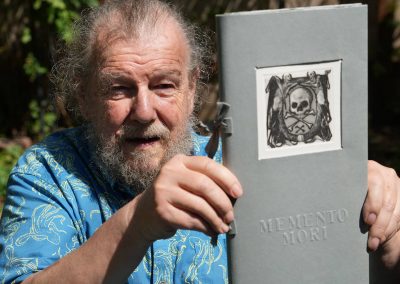

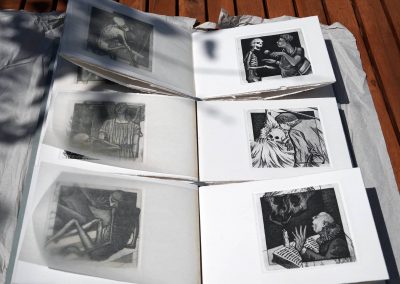

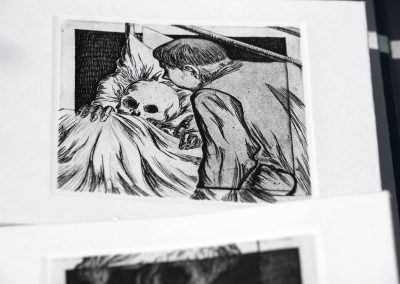

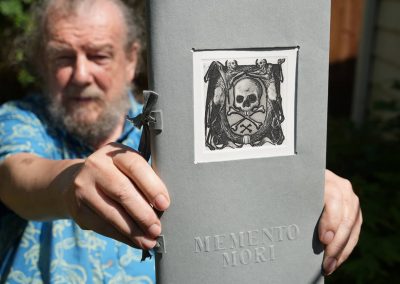

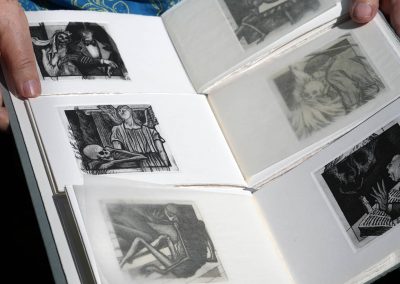

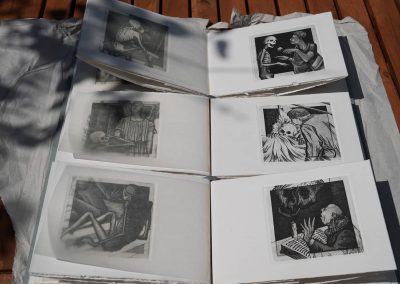

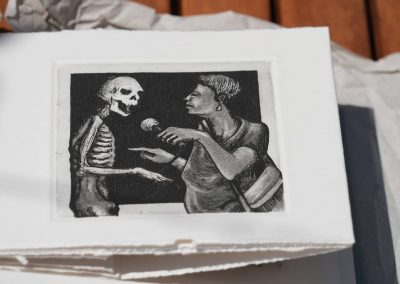

A meditative practice, artmaking helps him to cope with both the seen and unseen, that of this world and that which belongs in a space of imaginative interpretation. After the death of his father, Kutzer created a series of square etchings which he then had fashioned into a small edition of handbound books.

Of the series, Kutzer stated, “I first related to the medieval schema of the dancing death, but I didn’t only pick scenes from the traditional hierarchy – Pope and Emperor down to the beggar, but also tried more contemporary partners – reporter, clerk, alcoholic, and trash collector. Aside from individual partners, Death had also to deal with man-made catastrophes like death of forests, pollution of the sea, famine, and war.”

In this way, the enormous task of coping with the death of a loved one was transferred from an individual loss to one which encompassed the entirety of the world. The play of introspection and extrospection can be found throughout Kutzer’s work.

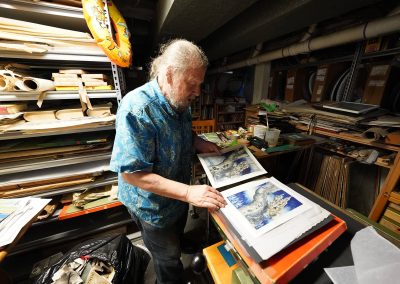

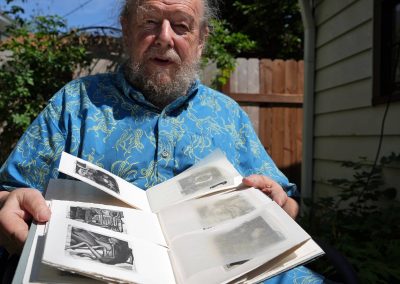

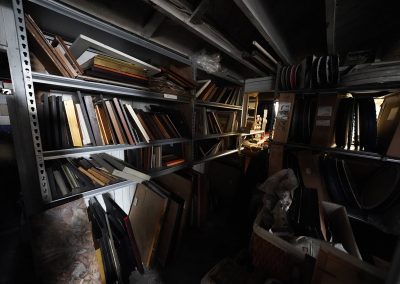

A copy of this “Memento Mori” book now lives in Kutzer’s basement, along with hundreds of other paintings and etchings which have found a temporary home on the shelves which create cavernous tunnels of Kutzer’s mind manifested on canvas, paper, and wood panels. Walking down the steps to his basement, it is easy to become immediately overwhelmed by the amount of finished works amongst assemblages of paint tubes and splayed brushes, crab figures and shells, and other props which are habitual characters in Kutzer’s art.

In the center of the back basement room is Kutzer’s printing press, the one cumbersome item he brought along from Germany. A partner in artmaking, he could not leave it behind in his journey across the Atlantic.

Once Kutzer moved to Milwaukee, an interesting transformation happened. The landscape paintings which called to his father began to call to him as well. All was new – his American wife, the natural environment filled with Lake Michigan vistas, and the genuine chance to start afresh.

In Germany he carried a chip on his shoulder about being a teacher instead of solely pursuing a career as an artist. Leaving that life and the perception of judgment from others behind, Kutzer clearly saw the change in himself and easily admits, “my paintings became more colorful and lighter.”

Oscillating between focusing on form and narrative, landscapes in Kutzer’s eyes were now more than listless pretty scenes, they had stories to tell. The etchings made with his printing press received a variety of gouache colors that entirely set the mood. A series of landscapes painted on circular targets had the role of showcasing our endangered environments and later even took on “a more spiritual direction using the rings as a symbol of the universe,” according to Kutzer.

Even with the shift in appreciating landscapes, his love of Classical mythology never left him, as Ovid’s Metamorphoses has more recently become an inspiration for countless scenes. It remains difficult to ignore the connection between Ovid’s metamorphosis and Kutzer’s own sense of transformation during this reflective stage in his life.

Aside from depictions on his canvases, the early influences of the Classics in his schooling nurtured a love of learning languages and deciphering historical texts. During his elementary school years, he learned German Kurrentschrift, a handwriting style which fell out of use by the early 20th Century.

When he learned of a series of diaries held at the Milwaukee County Historical Society written in Kurrentschrift by another German immigrant artist in Milwaukee, Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1845-1921), deciphering the text and learning of the kindred artist’s life became another calling for him. In the diaries, Kutzer experienced day-to-day life alongside Heine. More directly, it was within these diaries that Kutzer learned of Schlaraffia, a German-speaking fraternal club with the three pillars of friendship, art, and humor.

Reading about Schlaraffia’s history in Milwaukee, and discovering that the club still existed, Heine indirectly acted as Kutzer’s “godfather,” as he put it, guiding him to join.

Disconnected in time, these two German artists have become connected in place within their chosen home of Milwaukee. As Kutzer described it:

“It may sound strange to talk about a relationship with a person who died twenty years before you were born. But he was an artist too, and though battle paintings never were my cup of tea, some problems we do have in common as painters: technical problems, showing one’s work to the public, caring for a family and dealing with colleagues. Reading about his daily triumphs and defeats, his satisfactions and sorrows were, while deciphering his terrible handwriting, also mine. You suffer with him and enjoy with him. You agree and disagree with him, hope with him and feel relief. He and other people he talks about became part of my life. I was myself amazed, how it really hit me, when a friend of his suddenly died from the flu. I carry with me memories he imparted into me. There are still some shops in downtown Milwaukee or historical buildings he talks about in the diaries and when I pass them, they are not anonymous to me. His diaries helped me to feel at home.”

The vicarious friendship only exemplifies Kutzer’s approach to life and art. The relationship between the past and the present helped to form his Weltanschauung – a worldview – of simultaneous harmony and ambiguity. The distinctions between space and time, the known and unknown, coalesce into one reality, Kutzer’s.

Through his art the public can also experience this reality. And as fellow Milwaukeeans, perhaps we can partake in this special bond of place as well.