Vladimir Putin’s full-blown invasion of Ukraine aimed at toppling the Kyiv government, based on the preposterous claim that it is run by “neo-Nazis,” has produced Europe’s worst war in a generation, and it has taken a terrible toll on civilians.

The Russian armed forces have hit hospitals, apartment buildings, a shopping center and a theater that was serving as a shelter. The immense suffering has been made worse by sieges, above all the one around Mariupol, large parts of which have also been reduced to rubble.

The war has also forced millions from their homes. The UN high commissioner for refugees reports that more than 3.7 million Ukrainians have fled their homeland and that another 6.7 million have been internally displaced. The two figures together – children account for nearly half the total – comprise 20% of Ukraine’s population.

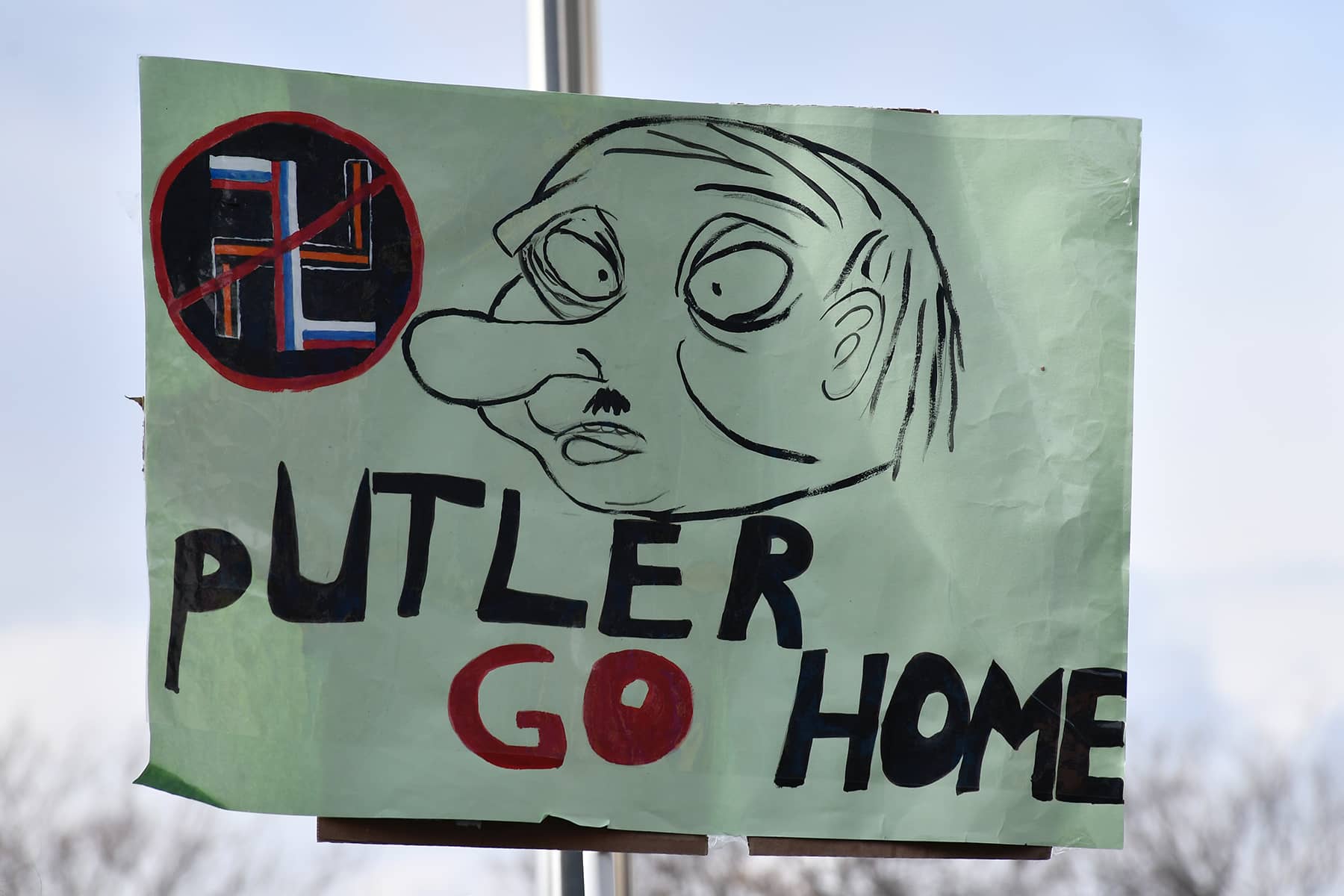

The shock and outrage at these and other dreadful consequences of Putin’s invasion are understandable, indeed appropriate. Animus toward Putin and the desire to make him pay a steep price, without delay, are running deep in the west, so much so that some believe that war cannot end so long as he remains in power.

Some American foreign policy specialists welcomed the prospects of regime change in Russia, while others opined that it should be the objective of U.S. policy – or said so only to backpedal once critics weighed in.

Not one for subtlety, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina declared that the war in Ukraine will not end until someone in Russia decides to “take this guy out” and followed up by saying that the only solution was for Russians to “rise up” and, referring to the 2011 uprisings in the Arab world, create a “Russian spring”. Carl Bildt, a former prime minister and foreign minister of Sweden, averred that peace in Europe requires regime change in Russia.

Although the Biden administration has disavowed regime change, its direct appeals to the Russian people are an obvious attempt to turn them against their government. President Biden’s off-script remark, during a visit to Poland following the 24 March Nato summit, that Putin “cannot remain in power” gave rise to speculation about his Russia policy and left his team scrambling to explain that toppling Putin was in fact not one of its goals.

Protests in Russia against Putin’s war, criticisms of it by prominent Russian tycoons and celebrities, and growing evidence that western economic sanctions are making Russians’ quotidian life much harder – because of shortages of basic necessities and rising prices – may strengthen the belief that this is the moment to bring Putin, and perhaps even his authoritarian political system, down.

We should assume for a moment that Putin does fall. What happens next?

One possibility: a new authoritarian leader replaces him, winds down the war in Ukraine in order to save Russia’s economy from disaster, and eventually seeks to repair the rupture with the west. Yet any successor to Putin who emerges from Russia’s current political order is more likely to share his animus toward Nato, and the west more generally, as well as his proprietorial attitude toward Ukraine. He – it is certain to be a man – may continue the war, using different tactics, for fear that a defeat could imperil his position even before he has time to solidify it.

A second outcome might be that Russians, weary of the war and enraged by the economic pain created by western sanctions, rise up and overthrow their government, eventually clearing a path to democracy. But a rebellion could fail, so those who hope for this result must ask themselves if it’s responsible to encourage a mass revolt when they are in no position to protect protesters from the massive repressive machinery at Putin’s disposal.

There is a third plausible scenario. Unrest in Russia segues into prolonged chaos, even a civil war pitting those who have a huge stake in the survival of the existing political order against their opponents who want to consign it to history’s rubbish heap. That could produce political turmoil, bloodletting, and a disarray in the world’s only other nuclear superpower – one that extends from Europe to the Pacific Ocean, has an area nearly twice that of the United States and land borders with 14 countries.

Theories of nuclear stability have always assumed that the countries that deter one another remain stable. We have no conceptual framework for understanding, let alone experience coping with, anarchy in a nuclear-armed country.

Can proponents of regime change in Russia be certain that the denouement will be the one they have in mind and are confident about? The dismal record of the United States and its allies in predicting the results of the regime changes they precipitated – in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya – are grounds for caution, not least because the consequences of getting this particular attempt wrong might prove disastrous.

Rаjаn Mеnоn

Cаglаr Оskаy, Gаyаtrі Mmаlhоtrа, Dеа Pіrаtеdеа, Аhmеd Zаlаbаny, Tоng Su, Hаnnа Bаlаn, Cаglаr Оskаy, and Mаrkus Spіskе

Originally published on The Guardian as What fantasies of a coup in Russia ignore

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.