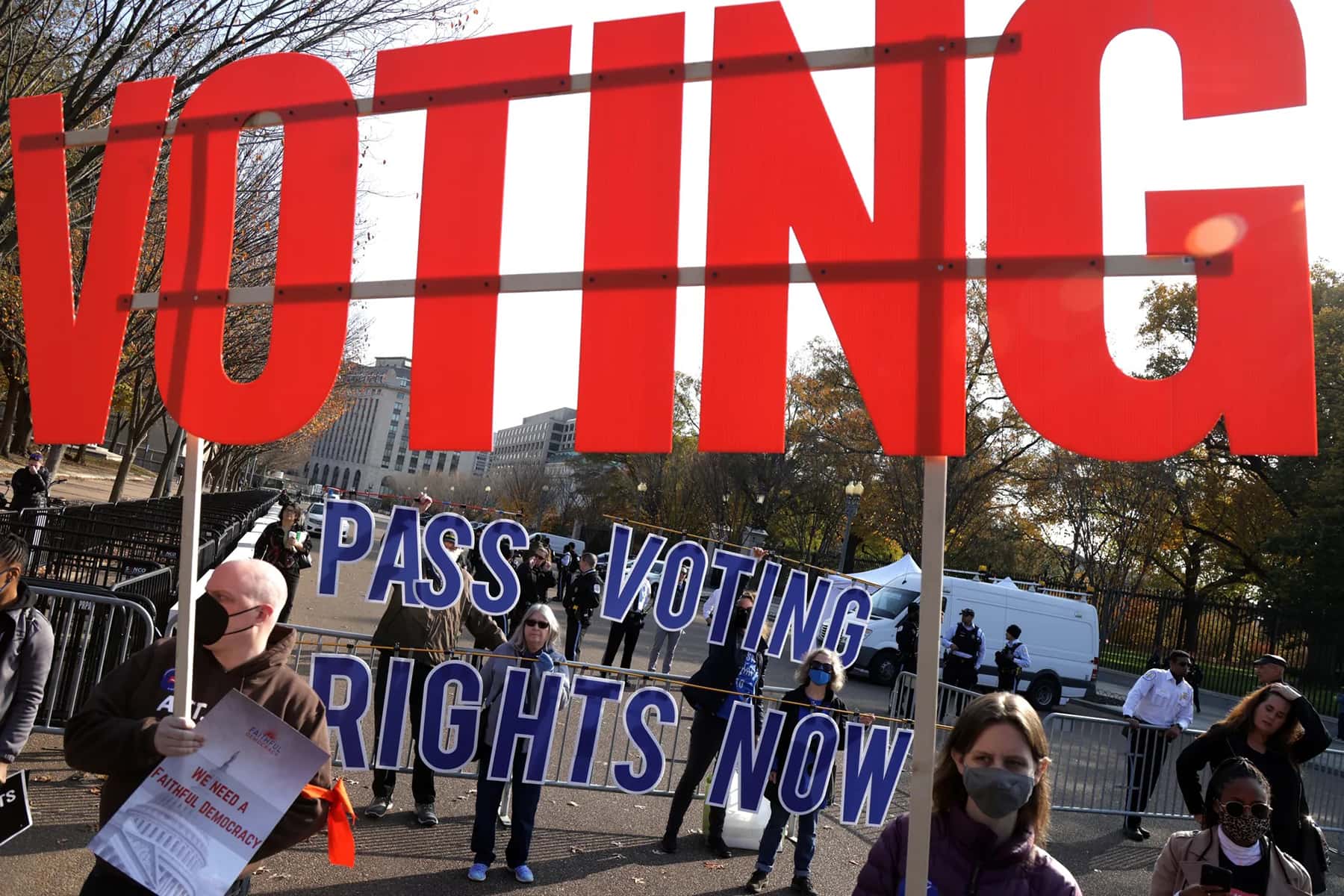

Republicans say they oppose the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act because it is an attempt on the part of Democrats to win elections in the future by “nationalizing” them, taking away the right of states to arrange their laws as they wish. Voting rights legislation is a “partisan power grab,” Representative Jim Jordan (R-OH) insists.

In fact, there is no constitutional ground for opposing the idea of Congress weighing in on federal elections. The U.S. Constitution establishes that “[t]he Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.”

There is no historical reason to oppose the idea of voting rights legislation, either. Indeed, Congress weighed in on voting pretty dramatically in 1870, when it amended the Constitution itself for the fifteenth time to guarantee that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In that same amendment, it provided that “[t]he Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

It did so, in 1965, with “an act to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution,” otherwise known as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a law designed to protect the right of every American adult to have a say in their government, that is, to vote. The Supreme Court gutted that law in 2013; the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act is designed to bring it back to life.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a response to conditions in the American South, conditions caused by the region’s descent into a one-party state in which White Democrats acted as the law, regardless of what was written on the statute books.

After World War II, that one-party system looked a great deal like that of the race-based fascist system America had been fighting in Europe, and when Black and Brown veterans, who had just put their lives on the line to fight for democracy, returned to their homes in the South, they called those similarities out.

Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt of New York had been far too progressive on racial issues for most southern Democrats, and when Harry S. Truman took office after FDR’s death, they were thrilled that one of their own was taking over. Truman was a White Democrat from Missouri who had been a thorough racist as a younger man, quite in keeping with his era’s southern Democrats.

But by late 1946, Truman had come to embrace civil rights. In 1952, Truman told an audience in Harlem, New York, what had changed his mind.

“Right after World War II, religious and racial intolerance began to show up just as it did in 1919,” he said. ”There were a good many incidents of violence and friction, but two of them in particular made a very deep impression on me. One was when a Negro veteran, still wearing this country’s uniform, was arrested, and beaten and blinded. Not long after that, two Negro veterans with their wives lost their lives at the hands of a mob.”

Truman was referring to decorated veteran Sergeant Isaac Woodard, who was on a bus on his way home from Georgia in February 1946, when he told a bus driver not to be rude to him because “I’m a man, just like you.” In South Carolina, the driver called the police, who pulled Woodard into an alley, beat him, then arrested him and threw him in jail, where that night the police chief plunged a nightstick into Woodard’s eyes, permanently blinding him. The next day, a local judge found Woodard guilty of disorderly conduct and fined him $50. The state declined to prosecute the police chief, and when the federal government did—it had jurisdiction because Woodard was in uniform—the people in the courtroom applauded when the jury acquitted him, even though he had admitted he had blinded the sergeant.

Two months after the attack on Woodard, the Supreme Court decided that all-White primaries were unconstitutional, and Black people prepared to vote in Georgia’s July primaries. Days before the election, a mob of 15 to 20 White men killed two young Black couples: George and Mae Dorsey, and Roger and Dorothy Malcom. Malcom had been charged with stabbing a White man and was bailed out of jail by Loy Harrison, his White employer, who had with him in his car both Malcom’s wife, who was seven months pregnant, and the Dorseys, who also sharecropped on his property.

On the way home, Harrison took a back road. A waiting mob stopped the car, took the men and then their wives out of it, tied them to a tree, and shot them. The murders have never been solved, in large part because no one—White or Black—was willing to talk to the FBI inspectors Truman dispatched to the region. FBI inspectors said the Whites were “extremely clannish, not well educated and highly sensitive to ‘outside’ criticism,” while the Blacks were terrified that if they talked, they, too, would be lynched.

The FBI did uncover enough to make the officers think that one of the virulently racist candidates running in the July primary had riled up the assassins in the hopes of winning the election. With all the usual racial slurs, he accused one of his opponents of being soft on racial issues and assured the White men in the district that if they took action against one of the Black men, who had been accused of stabbing a White man, he would make sure they were pardoned. He did win the primary, and the murders took place eight days later.

Songwriters, radio announcers, and news media covered the cases, showing Americans what it meant to live in states in which law enforcement and lawmakers could do as they pleased. When an old friend wrote to Truman to beg him to stop pushing a federal law to protect Black rights, Truman responded: “I know you haven’t thought this thing through and that you do not know the facts. I am happy, however, that you wrote me because it gives me a chance to tell you what the facts are.”

“When the mob gangs can take four people out and shoot them in the back, and everybody in the country is acquainted with who did the shooting and nothing is done about it, that country is in pretty bad fix from a law enforcement standpoint.”

“When a Mayor and City Marshal can take a…Sergeant off a bus in South Carolina, beat him up and put out…his eyes, and nothing is done about it by the State authorities, something is radically wrong with the system.”

In his speech in Harlem, Truman explained that “[i]t is the duty of the State and local government to prevent such tragedies.” But, as he said in 1947, the federal government must “show the way.” We need not only “protection of the people against the Government, but protection of the people by the Government.”

Truman’s conversion came in the very early years of the Civil Rights Movement, which would soon become an intellectual, social, economic, and political movement conceived of and carried on by Black and Brown people and their allies in ways he could not have imagined in the 1940s.

But Truman laid a foundation for what came later. He recognized that a one-party state is not a democracy, that it enables the worst of us to torture and kill while the rest live in fear, and that “[t]he Constitutional guarantees of individual liberties and of equal protection under the laws clearly place on the Federal Government the duty to act when state or local authorities abridge or fail to protect these Constitutional rights.”

That was true in 1946, and it is just as true today.

Congress also adopted the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919 and sent it off to the states for ratification, which it received in 1920. The 19th has the same language as the 15th but covers sex: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of sex,” an article Congress has power to enforce.

It is also worth noting, during this struggle over voting rights in America, how important it is to distinguish between voter fraud, which is vanishingly rare and has not affected the outcome of elections, and election fraud, which is coming to characterize a number of our important elections.

Voter fraud is about an individual breaking the law and is almost always caught. It is not a threat to democracy. Election fraud means that people in power have rigged the system so that the will of the voters is overturned. When it happens, it threatens to destroy our nation.

Now, as the contours of what happened on January 6, 2021, are becoming clearer, they appear to show a number of different schemes to overturn the election through fraud. At least one of those schemes appears to have been a coordinated attempt by members of the Trump administration and sympathizers around the country to overturn our government by committing election fraud.

As early as November 6, 2020, three days after the presidential election but before it had been decided, White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, who handled communication with the president, texted with a member of Congress about appointing alternate electors in certain states. Meadows told the lawmaker: “I love it.”

Biden was declared the winner of the election on November 7, 2020. That day, Meadows received an email suggesting “the appointment of alternate slates of electors as part of a ‘direct and collateral attack’ after the election.”

On December 1, 2020, then–Attorney General William Barr undercut Trump’s claims of voter fraud by telling the Associated Press: “[W]e have not seen fraud on a scale that could have [caused] a different outcome in the election.”

The true electors met in the states on Monday, December 14, 2020, and cast their ballots for Biden’s victory. Their states certified those ballots.

On the same day, on Fox & Friends, Trump advisor Stephen Miller announced that the campaign would overturn the election results and certify Trump as the winner. “As we speak today,” he said, “an alternate slate of electors in the contested states is going to vote, and we’re going to send those results up to Congress.” Ultimately, fake electors in seven states—New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin—sent fake ballots to Washington. Election law experts dismissed the possibility that these fake electors could accomplish anything; the certified ballots were the true ones.

That same day, December 14, 2020, Trump announced that Attorney General William Barr was resigning. His last day at work was December 23, 2020.

Barr’s deputy, Jeffrey A. Rosen, stepped up to become the acting attorney general. Meanwhile, at the Department of Justice, the freshly appointed acting head of the civil division, Jeffrey Clark, circulated a draft letter written to officials in Georgia, dated December 28, 2020, claiming falsely that the Justice Department had “identified significant concerns that may have impacted the outcome of the election in multiple states, including the State of Georgia.” The letter attempted to make that charge seem real by calling for an investigation (a technique Republican candidates have used since 1994 to allege voter fraud when they lost elections). The letter claimed that two sets of electors had met “in Georgia and several other States… and that both sets of those ballots have been transmitted to Washington, D.C., to be opened by Vice President Pence.” The letter asked the Republican-dominated Georgia legislature to choose which set of electors was the right one after taking the alleged voter fraud into account.

Clark circulated the draft letter to Rosen and Acting Deputy Attorney General Richard Donoghue, asking them to agree to it. “I think we should get it out as soon as possible…. Personally, I see no valid downsides to sending out the letter,” he wrote. “I put it together quickly and would want to do a formal cite check before sending but I don’t think we should let unnecessary moss grow on this.” Clark told them he wanted to send similar letters to “each relevant state.”

Several days later, Donoghue responded: “There is no chance that I would sign this letter or anything remotely like this.” He rejected Clark’s allegations: “[T]he investigations that I am aware of relate to suspicions of misconduct that are of such a small scale that they simply would not impact the outcome of the Presidential Election.” Later, Rosen wrote “I confirmed again today that I am not prepared to sign such a letter.”

In early January, Clark talked to Trump, who decided to fire Rosen and put Clark into Rosen’s place as acting attorney general. The remaining leaders in the Justice Department promised to resign all together if he did any such thing, and Trump backed down.

If the states themselves could not be used to invalidate the legitimate Biden electors, though, Vice President Mike Pence could. As vice president, Pence would be responsible for counting the states’ certified ballots. Lawyer John Eastman of the conservative Claremont Institute (and former law clerk for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas) wrote a memo suggesting that Pence, “or Senate Pro Tempore [Chuck] Grassley, if Pence recuses himself,” could claim that “because of the ongoing disputes in the 7 States, there are no electors that can be deemed validly appointed in those States.” Rejecting them would mean there were only 454 legitimate votes, and 228 would make up a majority.

In that scenario, “[t]here are at this point 232 votes for Trump, 222 votes for Biden,” Eastman wrote. “Pence then gavels President Trump as re-elected.”

Eastman’s memo continued: “Howls… from the Democrats…. So Pence says, fine…. [Since]… no candidate has achieved the necessary majority,” the matter goes to the House of Representatives, where each state gets a single vote. “Republicans currently control 26 of the state delegations…. Trump is reelected there as well.”

Eastman concluded: “The main thing… is that Pence should do this without asking for permission…. Let the other side challenge his actions in court,” where he expected the lawsuits would get thrown out because courts refuse to decide political questions.

The fly in this ointment turned out to be Pence, who, after conferring with advisors, steadfastly refused to act the part he had been assigned, a part that would have made him the leader of an insurrection and the obvious fall guy if things didn’t go as the conspirators had planned.

He also, though, refused to step aside, although there were clearly plans to make him do so. On January 5, Senator Grassley (R-IA) told a reporter that “we don’t expect [Pence] to be there,” and that he, Grassley, would “be presiding over the Senate.” His staff immediately walked that announcement back, saying it was a “misunderstanding.”

But Grassley’s statement reveals that the plan was widely known. Senior legal affairs reporter for Politico Kyle Cheney noted this weekend that Pence undercut those pushing him to deal with the fake electors by changing the language that explained what would be counted. The law says that the vice president must introduce all “purported” electoral votes. Pence added to the standard language that had been used for decades, saying that, according to the parliamentarian, the only votes that could be considered “regular in form and authentic” were those that had official state certification. Surely he would not have made such a change unless he felt the need to push back on those who would demand he acknowledge the fake ballots.

Frustrated by the vice president, Trump called on his followers who had planned a violent attack on the Capitol, possibly hoping to put enough pressure on Pence that he would change his mind; or to hold the lawmakers hostage until they agreed to his plan; or to slow down the process enough that the election would go to the House; or to slow it down enough that the Supreme Court, to which he had appointed three justices from whom he expected loyalty, would decide in his favor. At least four times on January 6, Trump tweeted about counting the forged ballots.

Miraculously, the plan failed, but Trump loyalists have been working ever since to make sure a repeat will not fail, passing new laws to suppress Democratic voters and take the counting of electoral votes out of the hands of nonpartisan officials and give it to Trump supporters.

This weekend, Trump told Republicans in Pennsylvania why he is focusing on races for supervisor of elections in 2022. “We have to be a lot sharper the next time when it comes to counting the vote,” he said. “There’s a famous statement: ‘Sometimes the vote counter is more important than the candidate,’ and we can’t let that ever, ever happen again. They have to get tougher and smarter.”

Voter fraud in America is vanishingly rare and has not affected the outcome of elections, and it is almost always prosecuted. But Trump loyalists used cries of voter fraud as an excuse to commit election fraud. Whether they will be prosecuted for it is an open question.

Аl Drаgо and Аlеx Wоng

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics