By Michael J. O’Brien, Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost, Texas A&M-San Antonio; and Izzat Alsmadi, Associate Professor of Computing and Cybersecurity, Texas A&M-San Antonio

Sorting through the vast amount of information created and shared online is challenging, even for the experts.

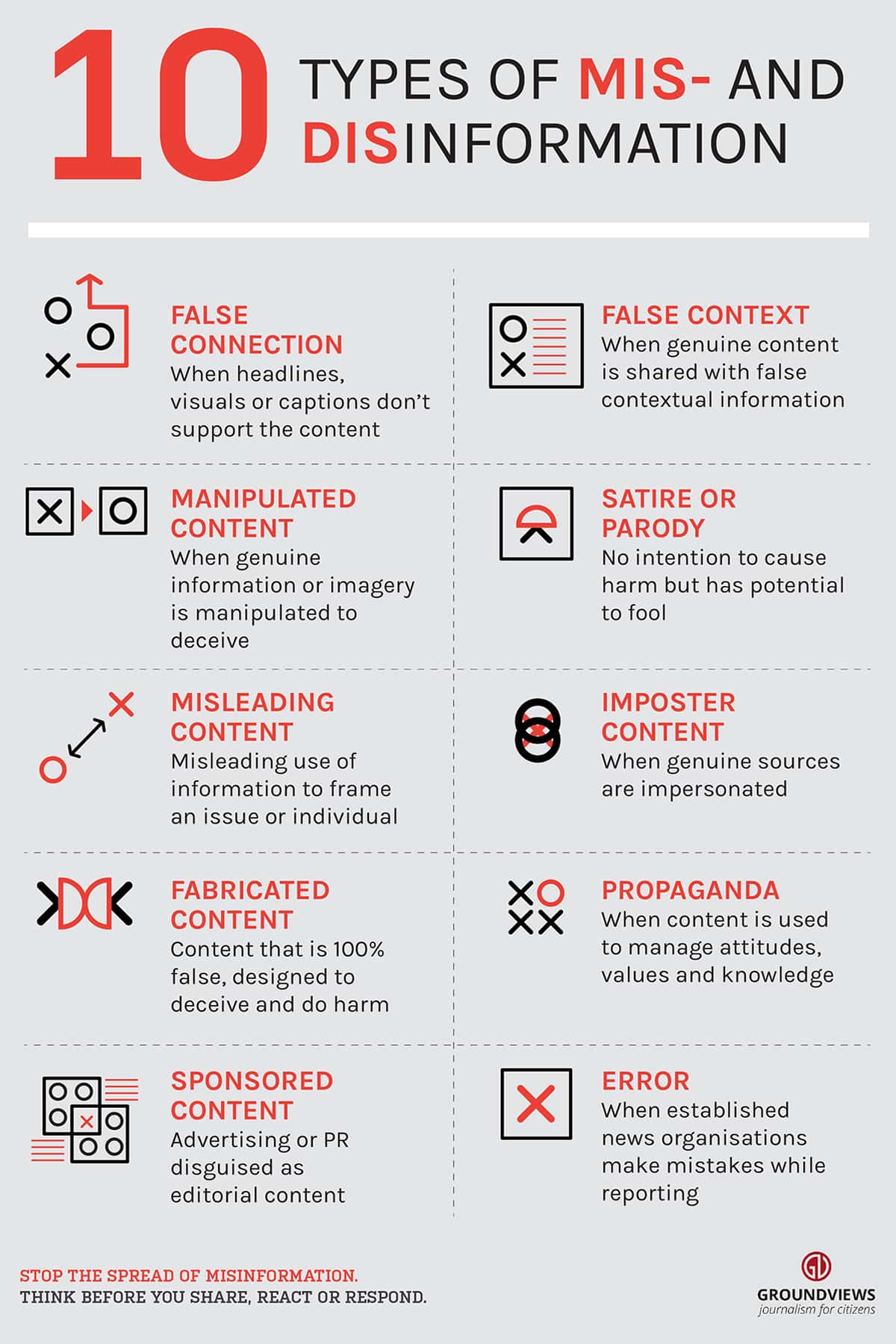

Just talking about this ever-shifting landscape is confusing, with terms like “misinformation,” “disinformation” and “hoax” getting mixed up with buzzwords like “fake news.” Misinformation is perhaps the most innocent of the terms – it is misleading information created or shared without the intent to manipulate people. An example would be sharing a rumor that a celebrity died, before finding out it is false.

Disinformation, by contrast, refers to deliberate attempts to confuse or manipulate people with dishonest information. These campaigns, at times orchestrated by groups outside the United States, such as the Internet Research Agency, a well-known Russian troll factory, can be coordinated across multiple social media accounts and may also use automated systems, called bots, to post and share information online. Disinformation can turn into misinformation when spread by unwitting readers who believe the material.

Hoaxes, similar to disinformation, are created to persuade people that things that are unsupported by facts are true. For example, the person responsible for the celebrity-death story has created a hoax.

Though many people are just paying attention to these problems now, they are not new – and they even date back to ancient Rome. Around 31 B.C., Octavian, a Roman military official, launched a smear campaign against his political enemy, Mark Antony. This effort used, as one writer put it, “short, sharp slogans written on coins in the style of archaic Tweets.” His campaign was built around the point that Antony was a soldier gone awry: a philanderer, a womanizer and a drunk not fit to hold office. It worked. Octavian, not Antony, became the first Roman emperor, taking the name Augustus Caesar.

The University of Missouri example

In the 21st century, new technology makes manipulation and fabrication of information simple. Social networks make it easy for uncritical readers to dramatically amplify falsehoods peddled by governments, populist politicians and dishonest businesses. Our research focuses specifically on how certain types of disinformation can turn what might otherwise be normal developments in society into major disruptions.

One sobering example we’ve reviewed in detail is a situation you might remember: racial tensions at the University of Missouri in 2015, in the wake of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. One of us, Michael O’Brien, was dean of the university’s College of Arts and Science at the time and saw firsthand the protests and their aftermath.

Black students at the university, just over 100 miles to the west of Ferguson, raised concerns about their safety, civil rights and racial equity in society and on campus. Unhappy with the university’s responses, they began to protest.

The incident that got the most national attention involved a white professor in the communication department pushing student journalists away from an area where Black students had congregated in the center of campus, yelling, “I need some muscle over here!” in an effort to keep reporters at bay.

Other events didn’t get as much national coverage, including a hunger strike by a Black student and the resignations of university leaders. But there was enough publicity about racial tensions for Russian information warriors to take notice.

Soon, the hashtag #PrayforMizzou, created by Russian hackers using the university’s nickname, began trending on Twitter, warning residents that the Ku Klux Klan was in town and had joined the local police to hunt down Black students. A photo surfaced on Facebook purporting to show a large white cross burning on the lawn of the university’s library.

A Twitter user claimed the police were marching with the KKK, tweeting: “They beat up my little brother! Watch out!” and a picture of a black child with a severely bruised face. This user was later found to be a Russian troll who went on to spread rumors about Syrian refugees.

These were a rich mix of different types of false information. The photos of the burning cross and the bruised child were hoaxes – the photos were legitimate, but their context was fabricated. A Google search for “bruised black child,” for example, revealed that it was a year-old picture from a disturbance in Ohio.

The rumor about the KKK on campus started as disinformation by Russian hackers and then spread as misinformation, even ensnaring the student-body president, a young Black man who posted a warning on Facebook. When it became clear the information was false, he deleted the post.

The fallout

Undoubtedly, not all of the fallout from the Mizzou protests was the direct result of disinformation and hoaxes. But the disruptions were factors in big changes in student numbers.

In the two years following the protests, the university saw a 35% drop in freshman enrollment and an overall enrollment drop of 14%. That caused campus university officials to cut about 12% – or US$55 million – from the university’s budget, including significant layoffs of faculty and staff. Even today, the campus is not yet back to what it was before the protests, financially, socially or politically.

The take-home message is clear: the world is a dangerous place, made all the more so by malevolent intent, especially in the online age. Learning to recognize misinformation, disinformation and hoaxes helps people stay better informed about what is really happening.

Originally published on The Conversation as Misinformation, disinformation and hoaxes: What’s the difference?

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.